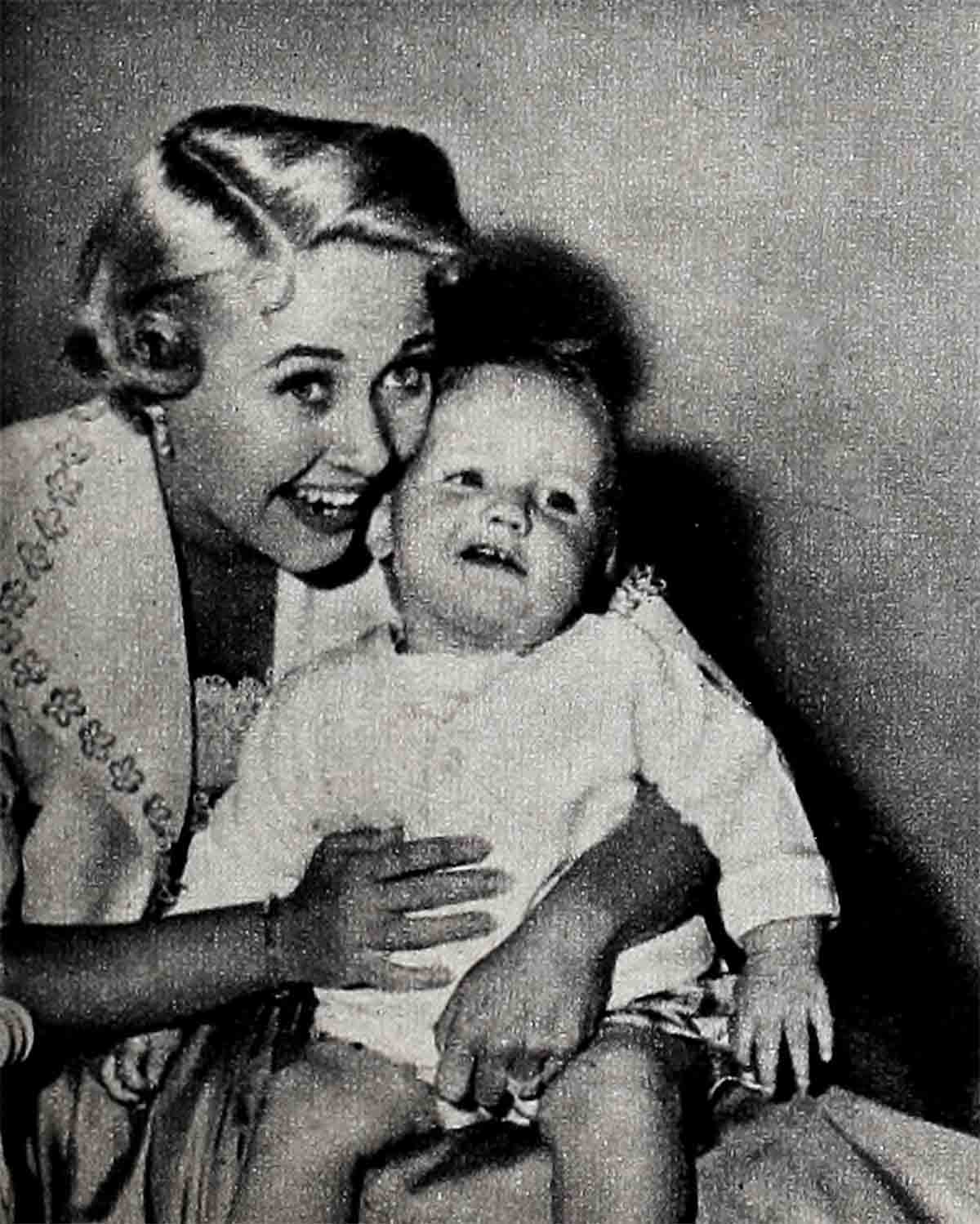

Room For One More—Jane Powell and Geary Steffen

ON A RECENT EVENING, a gray-eyed girl with silvery blonde hair, accompanied by a tall, proudly smiling man, had dinner at one of Hollywood’s better restaurants. They sat at a corner table, isolated and intimate, and they held hands between courses. They talked in brief phrases, needing few words to convey their thoughts; each could sense what the other was thinking. A couple who had just fallen in love? No, there was between them more than the magic of being newly in love. There was the magic of being married and being parents. About them, there was the glow of past as well as present happiness—and of future years together and children still to come.

At the moment, Jane Powell and Geary Steffen were talking about Jay, their sprout who was a year old in July, and the new baby, who is scheduled for a January debut. Said Jane, “We haven’t taken nearly enough pictures of Jay. Let’s make a resolution New Year’s Day: We’ll photograph both the children at least once a week. Nothing elaborate. Just snapshots when there’s sunshine, flash-bulb pictures when we have to shoot indoors.”

Geary went along with the idea. “And we won’t let ’em just kick around the house, either. Pictures like that become more valuable every year. What we ought to do is keep an album. Takes time, but I’ll make time. This could be a real family history—dates, special events. . . .”

“You know,” Janie said, “we now think we’ll always remember every single thing Jay does, but there seems to be more to remember all the time, and some of it’s bound to slip away unless we make a record of it, somehow. I’d like to get some movies of Jay’s reaction to music—the way he tries to hum the tune and sways back and forth. He really has a sense of rhythm! Of course, I guess a lot of babies do that, but I’d like to have it on record in case he does turn out to be a musical genius.”

“Not with those paws!” Geary grinned. “They aren’t designed for piano-pounding. He’s going to be a star quarterback. With those hands, he’ll heave the ball the length of the field. And run? Wait’ll you see him, with that build. Then he’ll be able to‘ give his younger brother a few tips—show him the ropes—when Kyle starts college. Kyle Amerson Steffen, Class of ’75 . . . They’ll probably nickname him ‘Kas,’ ”

Janie spoke up pointedly. “I think she will probably be called ‘Sissy’—around the house, that is. Miss Suzanne Hileen Steffen . . .”

“Or Suzy, Jr.,” Geary suggested (Suzanne Eileen being Jane’s real name).

“Definitely,” his wife said, “I think it’s better to have a boy, then a girl; then a boy, then a girl . . .”

“Keep right on going,” Geary urged. “Make it an even dozen!”

“Won’t it be wonderful?” Janie bubbled. But then there was a certain wistfulness in her eyes. In the pleasant room, in the midst of the mingled fragrance of good food and expensive perfume, in the warm atmosphere of comradeship and comfort, she was remembering a winter night long, long ago, a night when a dream was born. . . .

It was the 23rd of December, and Jane wasn’t more than thirteen or fourteen. She was trudging slowly home after choir practice, the music of Christmas still joyous in her ears. Caught up in the elation of the season, she still felt a vague heart-hunger. Jane was looking forward to the big day with a teenager’s normal eagerness. She was entirely happy in her home life with her mother and her father; yet among the absorbing interests and emotional satisfactions of her experience there was an empty space. She couldn’t have described her feeling even if a passing grade in English had been at stake, but the emptiness was there, elusive yet unmistakably, disturbingly real.

As she wandered along, listening to the lonesome sound of the wind in the pine trees, she asked herself silently. “What is it? What is it I miss?”

And then she saw the house with the great, lighted window. Cautiously she crossed the lawn, keeping in the shadows, but coming close enough to see the bright and busy scene within. A family was trimming a tall Christmas tree. There were five boys and four girls, supervised by the mother, the father and several other grown-ups who might have been uncles and aunts.

Jane knew then. that the holiday activities she watched were perfectly conventional, taking place in millions of homes. But for some reason they seemed to her very special and important. A boy and a girl got into an argument over the privilege of climbing the stepladder to place the angel at the top of the tree; the mother had to arbitrate. The baby insisted on trying to eat the miniature lightbulbs—particularly the red ones. A teen-age girl was wrapping a large and mysterious package and trying to dodge one of the older boys, who made teasing efforts to take it away from her. Two middle-size children were popping corn at the fireplace. One of the boys was stringing the corn; another was stringing cranberries.

Quite suddenly, Jane identified and understood the empty space in her heart. It was the niche meant for the brothers and sisters she’d never had.

At the discovery, the faint gloom lifted from the spirit of this only child, and a cheering warmth took its place. She was making herself a promise: some day she would be the mother in a duplication of this Christmas scene; she and her husband would be surrounded by children trimming the tree, bickering happily, enjoying the delights of this family holiday.

Of course. on that faraway night the girl who was Suzanne Burce hadn’t the remotest idea that she would become Jane Powell, world-famous movie star. She dreamed simply of becoming the wife of someone like Geary Steffen, the mother cf a baby like Geary III and of his brothers and sisters-to-be.

In the Hollywood restaurant, Geary was startled to hear his wife laugh suddenly and say, “Do you know, one of the first reasons I liked you was because you had such a nice brother and sister. And because your sister had two children. I said to myself, ‘Isn’t it wonderful to know that our children are all set with cousins in advance?’ I consider cousins almost as important as brothers and sisters,” Janie announced positively.

“Oh fine!” Geary growled. “And all the time I thought you loved me because I could give you diamonds.”

“That reminds me.” Janie tapped his shoulder with an admonitory forefinger. “No presents when the new baby is born. No more diamonds!” When Jay was born, Geary rushed to the town’s most famous jeweler to buy Jane a pair of magnificent earrings. “If you want to splurge,” Janie added, “just put the money into our New House Fund.”

That new house has been a family joke with the Steffens for over a year. They’ve been gradually outgrowing the little house they bought on a love-at-first-sight basis when they were newlyweds. and the arrival of the second baby will complete the process. But the Steffens have found the “perfect” home for themselves and the dreamed-of family that might well reach O’Sullivan-Farrow size.

This is how they found it: While they were driving around idly one Sunday, they passed a low, rambling English cottage of weathered red brick, with a wide-eaved shingled roof. It was surrounded by gardens vivid with bougainvillea, geraniums, copa de oro, lantana, petunias and even hollyhocks. A redwood stake fence enclosed a patio and a turquoise tiled pool.

Jane and Geary drove around it several times, exchanging breathless comments: “It’s vacant . . . How could it be? It’s so appealing . . . How much, do you suppose? . . .” Finally, they drove to the office of the real-estate firm listed on the “For Sale” sign, Jane keeping her fingers crossed all the way.

Yes, the agent said, the house was vacant. A very unusual house. He wouldn’t quote a price until they had seen the interior. He would meet them at the property with a key. “Today?” asked Jane.

Back they went, and the interior proved to be as much to their tastes as the exterior. There was a gracious living room with a deep fireplace, wide windows and a perfect spot for the television set; there were a family-size dining room, a big, homey kitchen, a paneled den with a second fireplace and floor-to-ceiling book-shelves (a good room for parents to retreat to when daughters start entertaining beaux); there were six great, airy bedrooms and six tiled bathrooms.

By the time they returned to the living room, the Steffens were walking in a dream that was spoiled only by a sense of foreboding: there must be a catch. Clearing his throat, Geary at last nerved himself to ask the vital questions about taxes, down payment, bank-loan appraisal . . . and price.

Jane gasped when she heard the figure; but she managed to turn the sound effect into a cough.

The figure might have referred to the cubic footage of the Empire State Building or the amount of postage necessary to carry a special-delivery letter to the moon; it had about that much relationship to the price a pair of junior householders with kids could afford.

“We must be going, Geary,” with great dignity.

But they talked about it all the way home—about the hardwood floors and the elegant fireplaces—about the wide windows and the huge closets—the ample cupboard space and the many built-in conveniences. Then, like many another young couple, they told each other staunchly that they certainly wouldn’t sink that kind of money into a house right now. Furthermore, think of the cost of carpets, draperies, furniture!

They didn’t sigh when they said it— not very much, anyhow.

They went home to the small house in which they are still living. Jane announced that the two upstairs bedrooms were adequate and would be for a long time. “We can set up screens to separate Jay’s half of the room from the new baby’s nursery. And the nurse loves her downstairs room; she’s comfortable. And the new baby won’t change that. We’re getting along fine here, and here we’ll stay—until people start putting sensible prices on things.”

The Steffens have formed an interesting habit. On the way home after an evening spent with friends, they often drive to the dream house and casually pull into the driveway as if they were about to enter their own garage and then turn the key in their own door. Sometimes, they walk up the moon-dappled path and around the broad, low veranda. “The trim around the windows needs repainting,” they’ll say. “Next time, let’s use forest green instead of black.” Pleasant make-believe . . .

To this day, the house remains unsold. Jane and Geary feel that it winks at them as they drive by. Sooner or later, they’re sure, they’ll be coming home to it. Meanwhile, they don’t mind waiting. It’s only reasonable to postpone moving until the stork’s intentions are clear, they tell themselves; then they’ll know whether they need one bedroom with blue draperies and one with pink, or whether they should plan on installing bunk beds in the boys’ dormitory.

With such a tangible dream in mind, small wonder that Jane was so firm about remembering the New House Fund and forgetting the diamonds when the new baby arrives. Over the coffee on that gala evening, she went on discussing the welcome-home arrangements. “We have to think about clothes, too. One thing’s sure: This baby won’t have any hand-me-downs to wear. Do you know, Jay’s used up every single one of the shirts and the soakers and the rubber panties and the blankets he started out with. Everything! And it looks to me as if that young man’s always going to wear out his equipment faster than he can outgrow it.”

“Is that bad?” Geary said. “What kid enjoys wearing his big brother’s old clothes?” (Note that Geary’s sticking to his hunch about the new baby’s sex.)

“But if the baby’s a girl she’ll want to wear Jay’s clothes,’ Jane explained. “When I was in school, I was so envious of the girls who had older brothers that they could borrow shirts and levis from. You know—in your teens, brand-new clothes of your own are never as sharp as outfits that somebody else has broken in. They have to be a little bit faded and frayed to look cool.”

It was understood between Jane and Geary that certain items Jay hasn’t had a chance to wear out will become hand-me-downs. Boy or girl, the new Steffen will inherit some of the silver porringers, silver comb-and-brush sets, silver flatware and silver cups that were showered upon Jane before Jay’s arrival. She rationed her firstborn to one each of the handsome gifts, and the duplicates were placed in a safe-deposit box to be initialed for the brothers and sisters to come.

If the newcomer is a girl, she will eventually inherit one of her mother’s dearest possessions, a gold signet ring that was given to Jane on her seventh birthday. Jane still wears it and swears that she’ll continue to wear it until she has a daughter who has grown up enough to treasure it too. By that time, Jane hopes, she’ll have to buy a few similar signet rings to keep the peace among several daughters.

Thinking of souvenirs for herself, this sentimental mother plans to preserve the new baby’s first walking shoes by having’ them cast in bronze and set on weighted bookend bases. She has her own scuffed and wrinkled baby shoes (saved by her mother) ready to be combined with Jay’s first walkers to form another pair of bookends.

Then there is the final bit of preparation for Miss or Master Steffen—a very important aspect that comes up whenever Jane and Geary discuss this delightful topic. It is, in keeping with modern techniques of child-rearing, the indoctrination of Jay. The Steffens decided well in advance that Jay was to hear the word “baby” often enough that its sound would be familiar to him. He was to see his mother cuddling a doll or a teddy bear wrapped in a blanket often enough that he would accept this behavior as ordinary and everyday, not as a threat to his own position in the household.

On the set of Metro’s “Small Town Girl,” a fellow player asked Jane how she was getting along with this task. “Not very fast,’ she admitted. “I’ve explained to him over and over that he’s going to have company, and told him how wonderful it will be to have a little brother or sister. He listens to me with a bright look on his face, but I’m not sure he understands a word I’m saying. After all, its an awfully complicated idea for such a little boy to grasp. And I don’t think he’ll ever learn what the word ‘No!’ means.”

But a few days later Jane was able to report progress. The night before, she had been holding a doll, and Jay decided to take it. “But I want to hold the baby,” his mother protested.

Master Jay tucked the Raggedy Andy under his arm, tottered to his own chair, sat down with the doll on his lap, and rocked back in forth in perfect imitation of his mother.

“No,” he said.

He had learned a new word. And at the same time he had shown some understanding of the needs of Raggedy Andies.

“So I guess everything will work out all right,” his proud mother sighed. “And we’ll have a much better idea how to go about it next time.”

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE NOVEMBER 1952

No Comments