Unforgettable Article On Elizabeth Taylor

magine you are Liz Taylor—Star . . . Actress . . . Woman.

Suddenly your sweet dream of warmth and innocence and love turns into a horrible nightmare.

Your fans betray you.

Crowds greet you with hostility.

You are in a hospital—badly erippled, desperately ill. gasping for breath, barely hanging on to life. The one person you love most in t he world dies.

You change your religion in a desperate bid for peace.

You are very beautiful—but you are alone, bereaved by the death of your loved one, vilified by those who once worshipped you, stripped of health.

Your beauty seems more a curse than a blessing for it seems to bring you only heartache and emptiness.

But with everything that has happened, the most horrifying of all is the blinking eye that seeks you out wherever you go. It pursues you on the Street, it follows you into Stores and restaurants, it breaks into your home. You shut your own eyes tight to keep the horrible eye out, but there it is!—penetrating your mind, invading your heart, taking power over your soul.

You dream a nightmare and awake. A flick of a switch and light floods into your bedroom. The eye is gone. Your torment is over. With light—and with the coming of the day—the nightmare fades and soon it is a vague, uneasy memory.

Yet, suppose—just suppose— that you can not wake up, that your nightmare goes on and on and on. Even if you do wake up, the horrible blinking eye is still there. Awake or asleep, your agony never stops, your torment never ceases.

If you can imagine this—day and night blurring together into one continual nightmare—then you know what it’s like to be Liz Taylor. Each episode in the nightmare differs slightly from the others, but the overall pattern is always the same. Nothing new ever happens— just endless variations on torment and pain.

Liz Taylor’a recent near-fatal bout with double pneumonia, complicated by anemia, is just such a dramatic variation on an old theme. She’s had double pneumonia be- fore (she’s been plagued by respiratory diseases since she was a child; in fact, her marriage to Nicky Hilton was almost postponed because she was suffering from a throat infection), and this is far from being her first brush with death. But it was the most serious.

WHEN LIFE WAS INNOCENCE

Let’s go back and relive the scene as if it were happening today. The London Clinic, the 200-year-old hospital where doctors are waging a superhuman fight to save her life, is exactly the same place where she was bed- ridden with meningism (a virus inflammation of the membranes of the brain) just a few months ago.

Her personal physician, Dr. Carl Heinz Goldman, is the same doctor who cared for her before. The other physicians are—Lord Evans, physician to the Queen; Dr. Terence Cawthorne, surgeon; Dr. Joseph Smart, Dr. Middleton Price, anesthetist; and Dr. V. C. Rattner—but behind their gauze masks, their features are indistinguishable from the faces of the numerous other medical men who have hovered over her so often in the past.

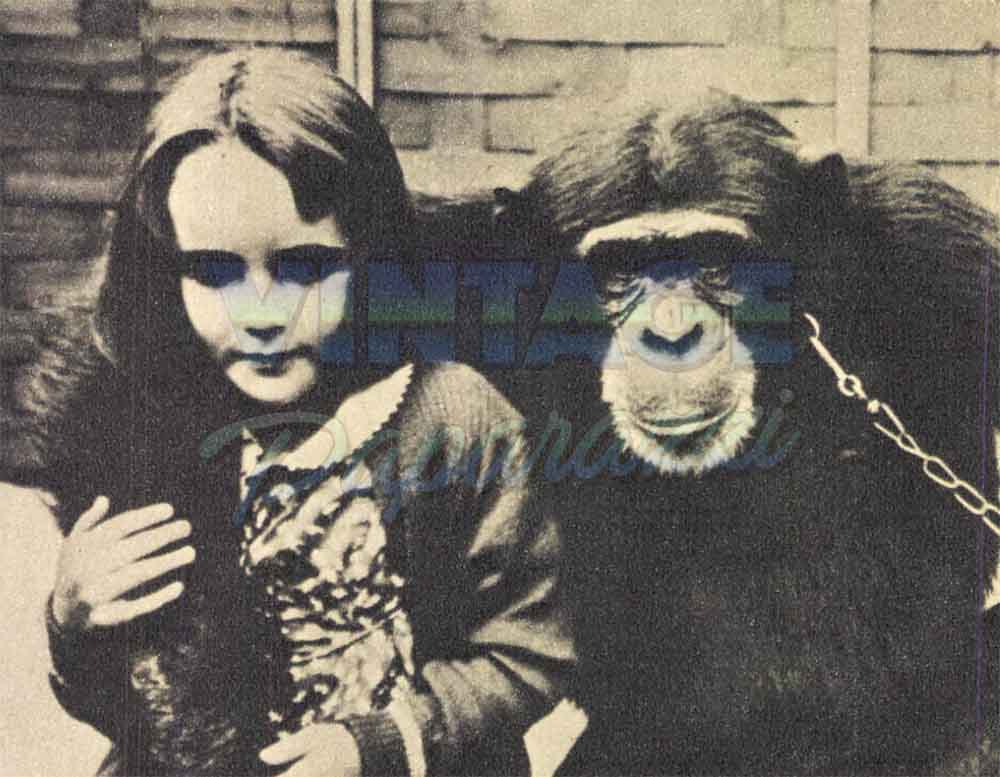

Visiting zoo at age 4, Liz met friendly chimp, decided that she loved animals, a decision which affected her life later.

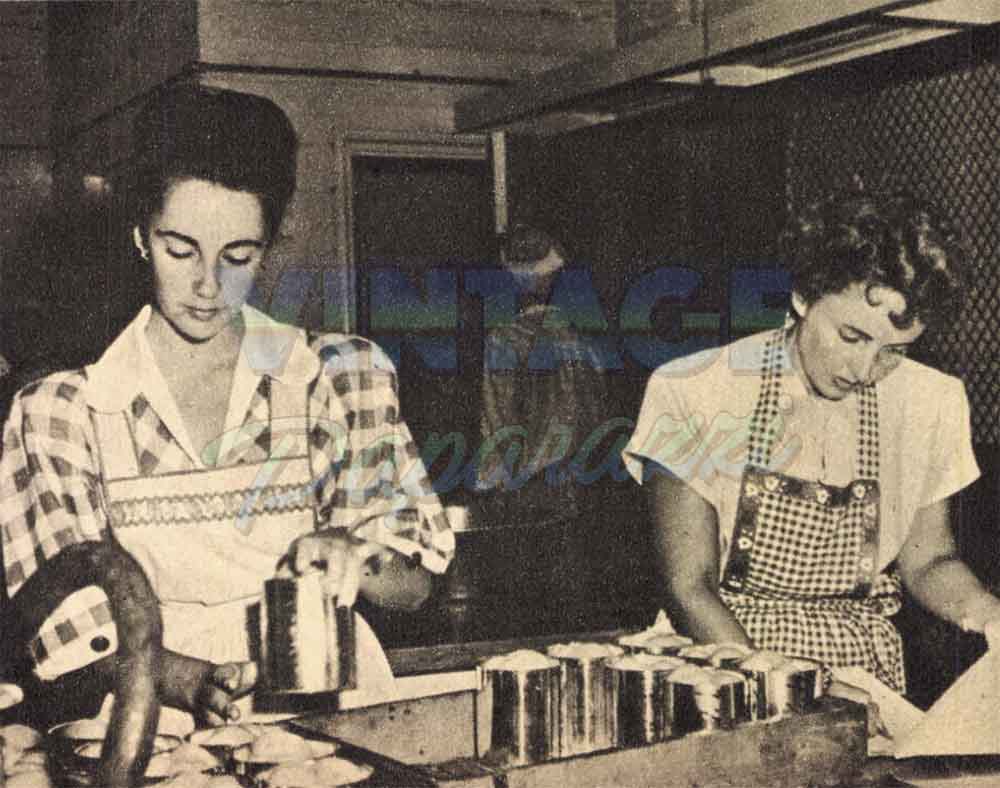

To learn practical side of life when she was in high school, Liz’ mother sent her to cannery for a course in home-canning.

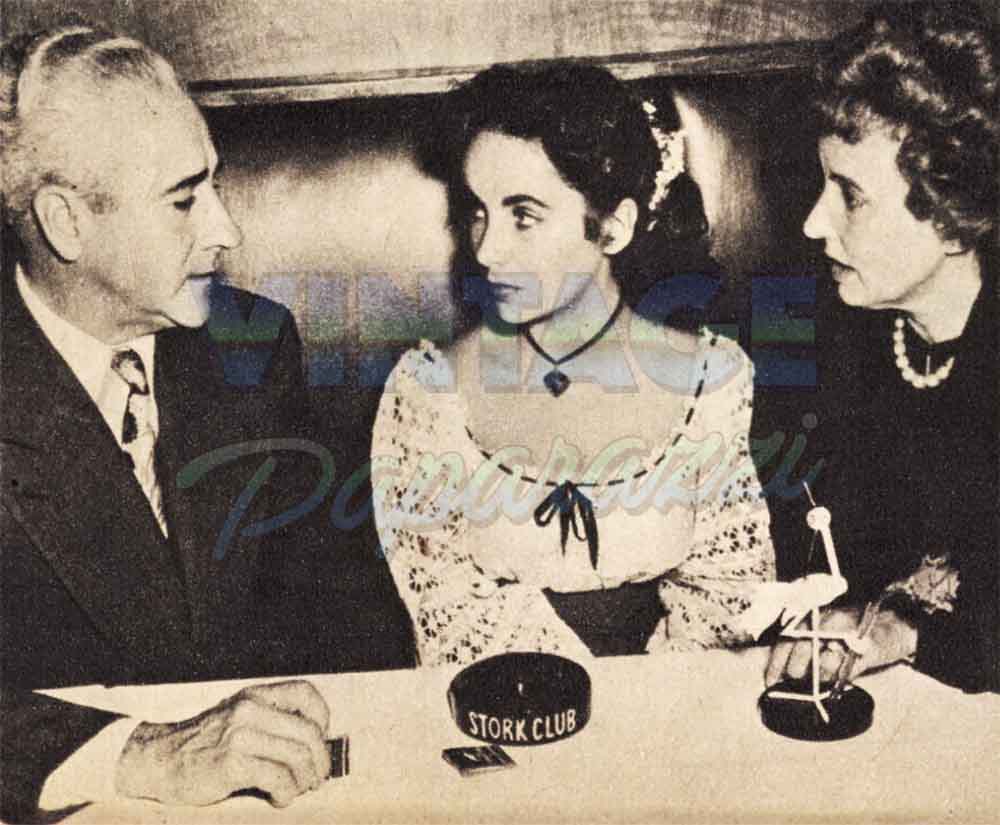

The people outside in the hall—those who worry and wait and pray—are easily identifiable. Eddie Fisher, her husband, who has paced hospital corridors helplessly on numerous occasions in the two years of their marriage. Just as Mike Todd had paced hospital halls before him. And before that, Mike Wilding.

Her parents, Mr. and Mrs. Francis Taylor; her friend, John Wayne; Eddie’s agent, Milton Blackstone; producer Joseph Mankiewicz; Liz’ press secretary, Suzanne Cardozo; director Rouben Mamoulian; actress-model Bettina; and secretary Dick Hanley—all well-known, easily recognized people, yet all shadows and ghosts of those countless other friends, co-workers and confidantes who have stood vigil by Liz Taylor’s bedside in the past.

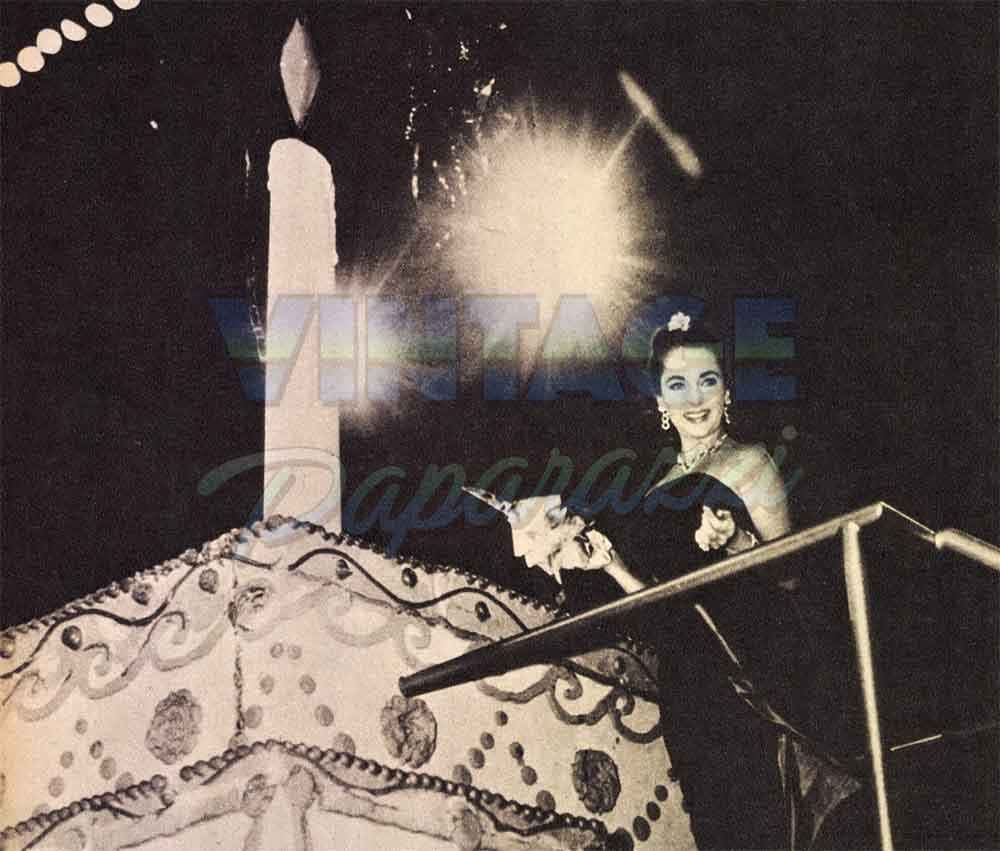

The Pleasure Of Stardom:

YOU HAD YOUR CAKE, LIZ, AND ATE IT, TOO!

Outside on the Street stands the crowd. Anonymous men, unknown women, ordinary youngsters, who are United, by concern for Liz Taylor, with all those other thousands of men, women and children who have adored and hated, cheered and vilified, prayed for and cursed her ever since she first burst upon the silver screen in National Velvet.

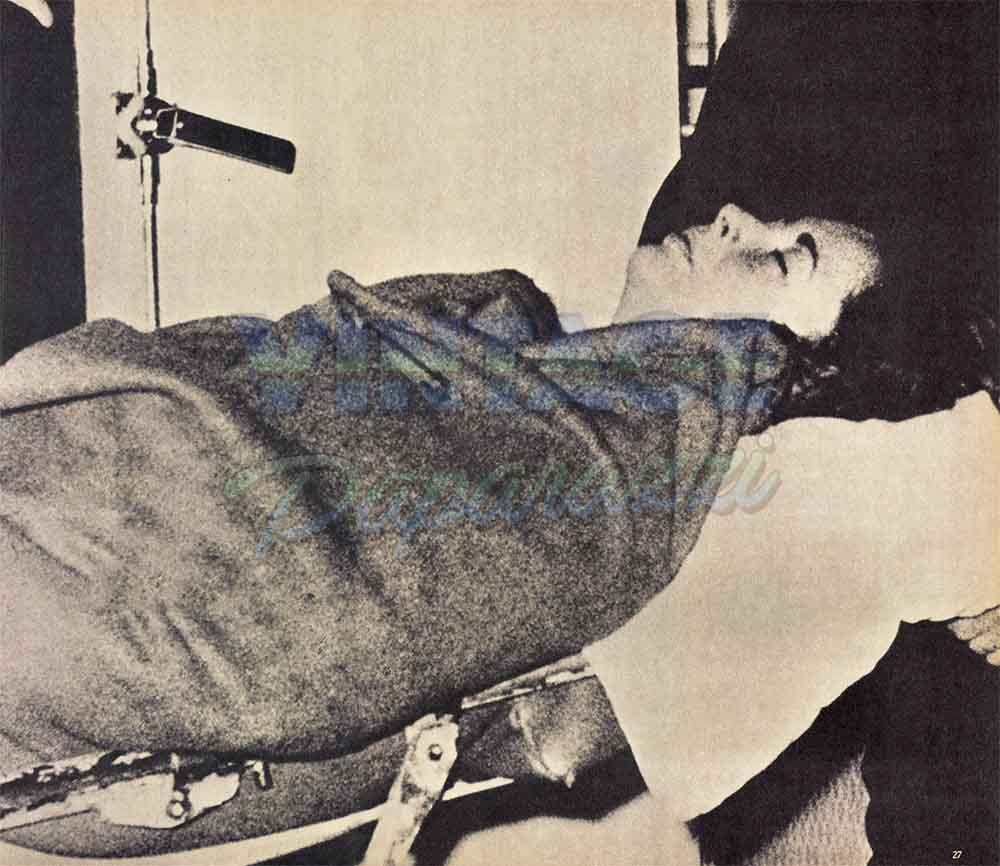

Liz Taylor herself? The details of this scene are different, but the general outlines are most familiar. A white hospital bed, clean, antiseptic. A chalk-white face. Long black hair jerked back from her forehead by a wad of surgical tape. Feet elevated. Drip tube in her ankle feeding her intravenously. A 700-pound square electronic lung looming over her like some grotesque animal. From the electronic lung stretches a tentacle-shaped rubber tube which winds down to the bed and enters the patient’s body through a two-inch insertion in her windpipe. Another tube transfuses blood into her arm.

The Passion Of Love:

YOUR HEART ALWAYS RULED!

Liz Taylor is in a coma, her lungs are mucus-clogged. A weary doctor steps away from her bed for a second, sadly shakes his head ”no” to a nurse, and then bends over the patient again.

Suddenly, the ever-present eye is nearby. Even when she is unconscious, the eye is never far away. This time, it’s small, unobtrusive, the tiny, ferreting eye of a miniature camera.

Somehow, nearby, a photographer is plotting ways to invade her hospital room. At the very moment that the fingers of death are reaching out, the horrible eye is hunting her . . . looking for her . . . looking for her . . . as it has done thousands of times before . . .

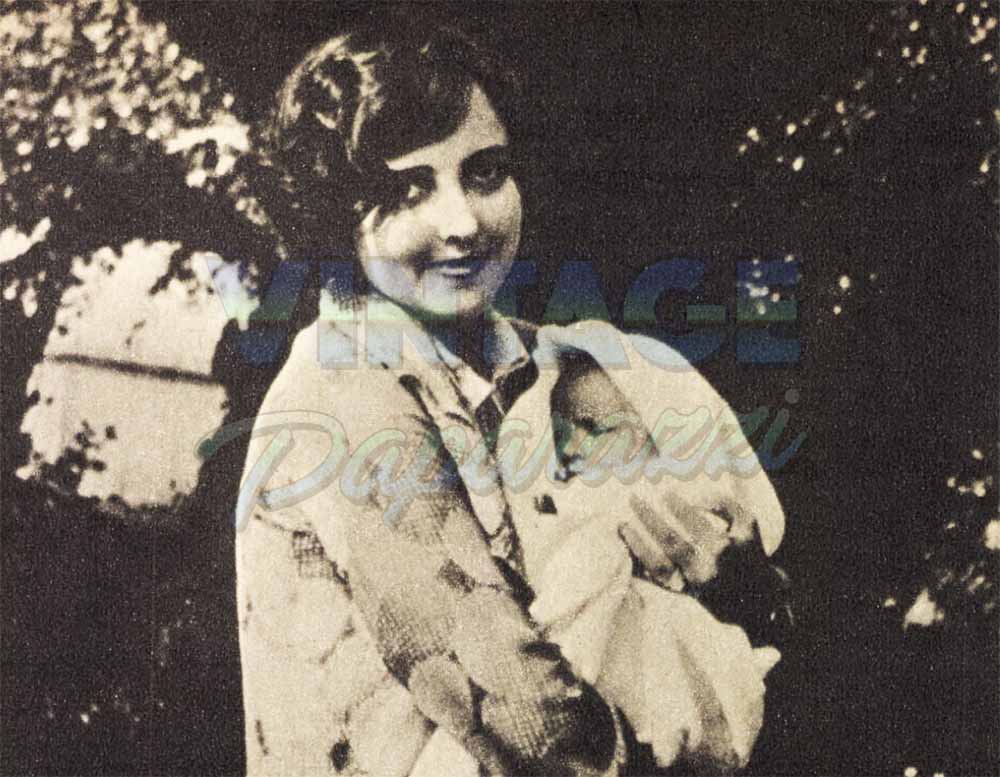

Childhood—the sweet dream of warmth and innocence and love. Mama is beautiful and Papa is handsome and brother Howard is so much older—two years older—but he’s nice, sometimes, except when he teases. Cats are soft and furry, dogs are rough and fuzzy, but best of all is the chipmunk, Nibbles. He sits on your shoulder, and you tell him your most secret secrets.

THEN THERE WAS THE PAIN OF NOTORIETY!

Nibbles understands everything, and you love him as much as Mama and Papa and Howard.

You take Nibbles along when you go from house to house in Beverly Hills selling stuff you find around your house—soap, matches, combs, old toothbrushes, cigarettes, fancy boxes, faded flowers and silver trays. The people in the mansions laugh when you tell them what you’re selling. You don’t know why they laugh exactly, but you laugh with them, and you find out that when you laugh they often buy something.

Your brother shows you how to use a box-camera. There’s a little eye in the front. You point at someone, and click the thingumajig, and sometimes, if you’re lucky, you get a picture. Once in a while, Howard snaps your picture. Your favorite is the one with the top of your head cut off.

When you’re eight years old, your mama takes you to a movie studio, Universal Pictures, and soon you’re acting in front of a camera. There are lots of lights, and the camera has a big eye, like a sick dog, hut acting’s kind of fun, although you only get to make one picture that year.

One day, you don’t have to go to the studio any more, but you don’t mind ’cause now you have more time to spend with all your dogs and cats, and, of course, with Nibbles.

But a year later, you’re back in front of the cameras, this time at a studio called MGM in a picture called Lassie Come Home. It’s fun playing with Lassie, even when the big eye is blinking at you, but it’s still more fun to get home to Nibbles.

Then you’re in a film called National Velvet. You’re crazy about the horse you ride in the picture, and you have the best time you’ve ever had in your life. Even rehearsing is great—every day you make at least 40 jumps on horseback, until one time when you fail badly you are knocked unconscious. After that, being in National Velvet isn’t quite as much fun any more.

The picture comes out and you’re a big success. You don’t know what success is exactly, except that now you never seem to have time for Nibbles. You’re at the studio from 8:00 in the morning ’til 6:00 at night. You go to classes at the studio school, you study three hours a day at the studio classroom, you act and rehearse in front of the blinking eve of the studio camera until you’re dead tired. Your free time is spent giving interviews, studying lines, having fittings, and being made up. Always a studio representative, or a press agent, or your mother is with you.

Without knowing when it happens exactly, one day you stop being ”you,” Liz Taylor, and become ”she,” Elizabeth Taylor, movie star. For this little girl, ordinary life is gone forever.

For Elizabeth Taylor, movie star, the camera eye becomes her master. Her mother stands right behind the camera, giving hand signals to her: ”smile more;” ”take is easy;” ”more emotion;” ”soften your voice.” Her mother, the director, the producer, and, above all, the camera eye—tell her constantly what to say, what to do, what to feel.

There’s no place to hide, no place to run to. Everything’s geared to a tight schedule, everything must go off like clockwork. Years later, she was to recall, ”In school, we weren’t even allowed to daydream. So I’d escape to the girl’s room.” But even there the insistent voice of the studio reaches her: ”Call for Miss Taylor. Call for Elizabeth Taylor. On set in five minutes.” And she returns from the world of her dreams to the real world of the glaring camera eye.

Once in a while, she manages to retreat into the prop and costume department where she can enter the land of make-believe. She dresses up in different costumes. She can be anything she wants— a ragamuffin or a princess, the ugly stepsister or Cinderella.

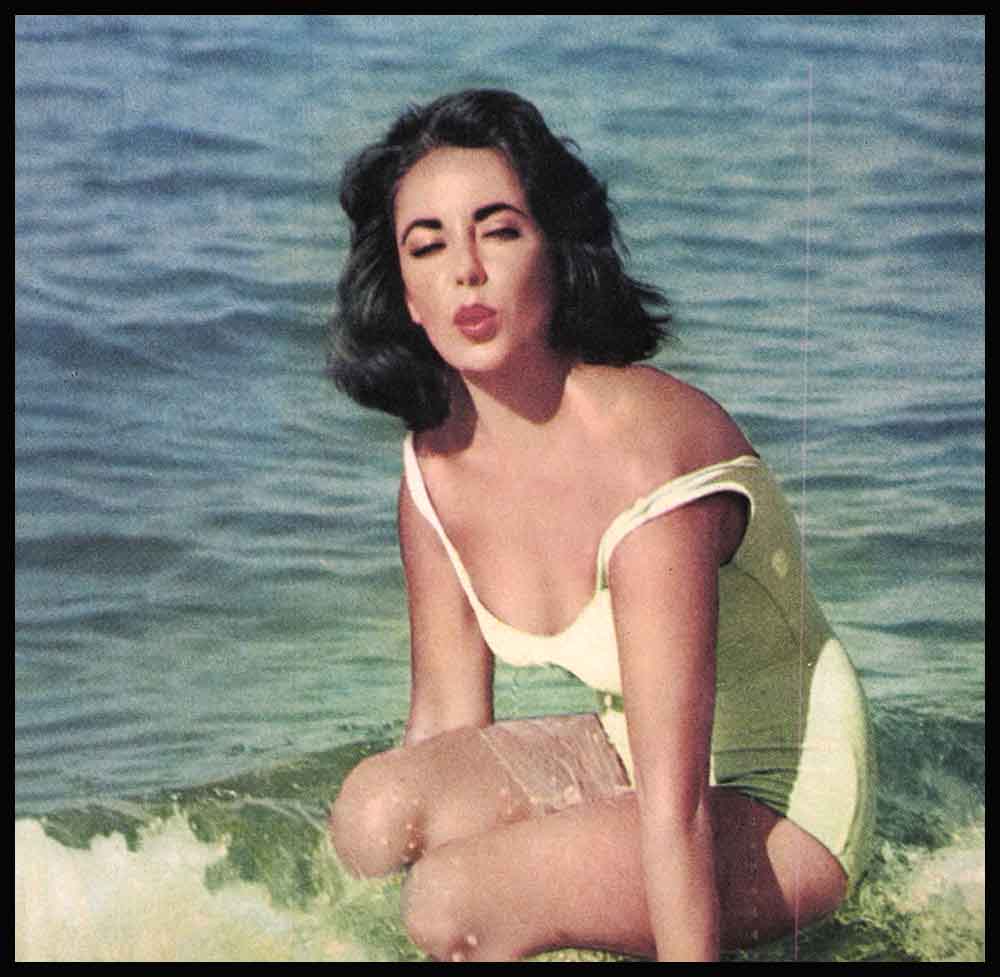

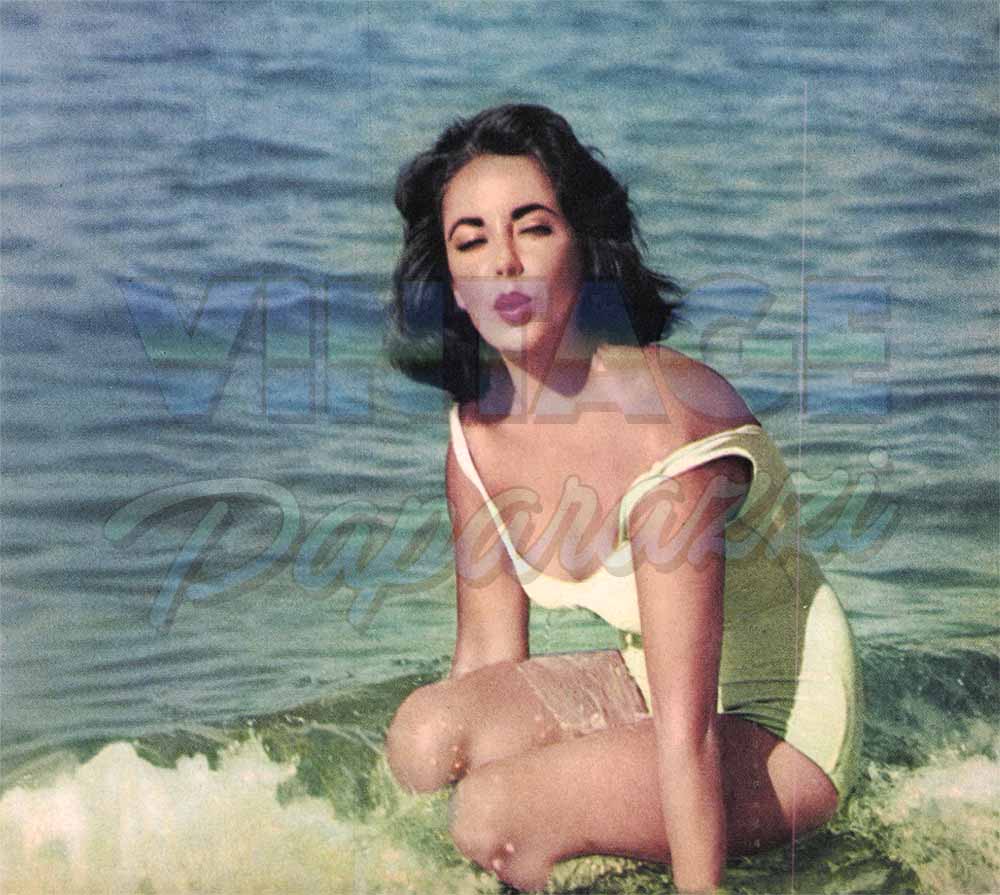

One day, she puts on a low-cut peasant blouse and a flared skirt. She makes up her face—rouge, lipstick, eyebrow pencil. Then, frightened at her own audacity, she walks quickly to the crowded studio commissary.

As she flounces past the tables, every man in the room turns to stare at her. Her huge violet-blue, double-lashed eyes sparkle. She swings her coal-black hair as she moves. Her low-cut blouse and tight. skirt make one thing amply evident. Elizabeth Taylor, at 14, is a woman.

Not just a woman, but a beautiful woman. As one MGM official put it, “I have known some of the most beautiful women in the world, but she is the most beautiful I have ever seen.”

The studio and her mother close ranks to protect this beautiful property. They screen her dates, and all the males who ask her out are found wanting. They are either too young or too old; too famous or too unknown; too handsome or too unphotogenic.

When they finally allow her to date, it is only on studio-arranged, heavily chaperoned, publicity affairs.

The camera eye— the still camera instead of the movie camera—is always focused on her. How can you be natural with a boy when a chaperone is always with you? How can you really talk to a boy if a reporter is jotting down your every word? How can a boy get up the courage to kiss you—when you want him to kiss you—when a cameraman is there every moment waiting to catch the clinch?

She doesn’t have a real ”alone with a boy” date until she is almost 17. Oh, sure, she goes to a party when she is 16, Roddy McDowall’s birthday party, but she goes alone, and returns home alone, and no one asks her to dance all evening. In the eyes of the boys, she is too beautiful, too famous, too perfect.

She wants to run away, to become just another girl, to escape the incessant glare of the camera eye. But she doesn’t know where to run, or how to run, and she is afraid. But her brother Howard has found the way. When your mother arranges a screen test for him, he shows up for it all right, but first he shaves off all his hair. This accomplishes two things at once: it stops the screen test then and there; it discourages his mother and she never speaks of a movie career for him again.

But Liz has no such direct methods of rebellion. She can only stew inside and sulk. She is so over-protected, over-pampered and over-directed that she just doesn’t know how to deal with other people at all. She makes appointments and breaks them, or she shows up very late.

When someone asked her what she did during the period before she showed up late for a date, she was quoted, ”What do I do for so long? Well, I tint my fingernails, then my toenails, I cut my hair. I pluck my brows. I brush and rebrush my hair. Also, I do all my daydreaming when I’m waking up. I sit with lipstick in hand reliving a scene that took place last week, wishing I’d said this instead of that.”

Only her daydreams are her own. When she sneezes. the world says, “God Bless You.” When she says ”hello” to a boy, the columnists report the next day that she is engaged. She goes out with Glenn Davis just seven times, and the papers say they are about to elope. Her romance with William D. Pawley, Jr., is covered on the front pages of every newspaper. Sometimes it seems that if she and Bill might somehow manage to slip away to an uninhabited desert island, a photographer would be sure to be waiting there for them when they step off the boat. In a gale of publicity she and Bill are engaged; in a tornado of newsprint they finally announce their ”disengagement.”

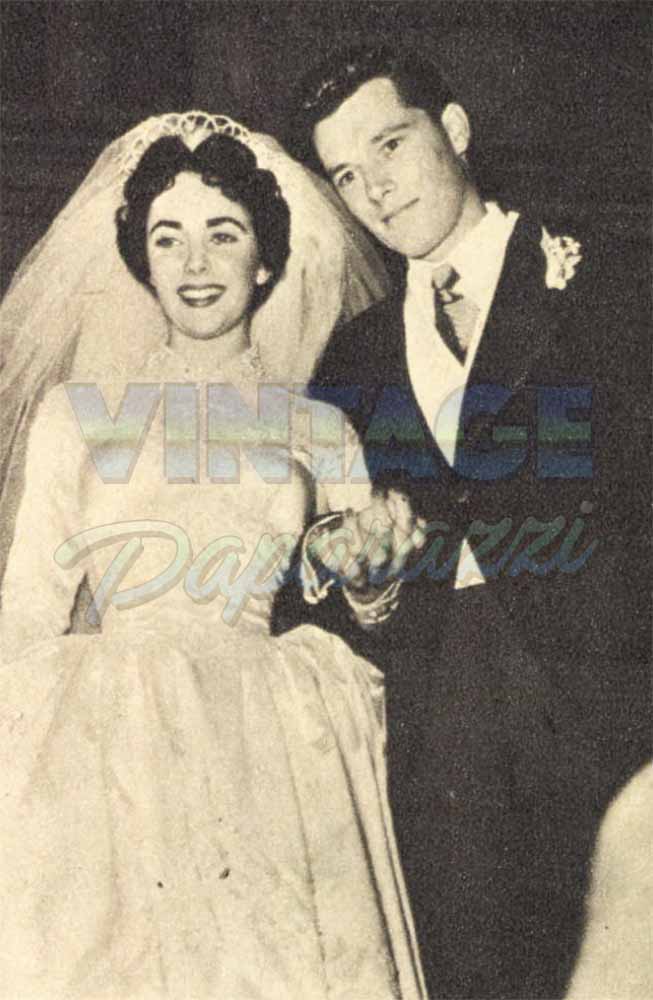

Nevertheless, all this is just a mild breeze compared to the cyclonic hoopla that marks her actual wedding—to Conrad Nicholson Hilton, Jr., two months after her eighteenth birthday. “All my life, since I was a little girl,” Liz once complained, ”people have been saying to me, ‘Go there, do this, say that, wear this, don’t do that!’ ” And if her wedding to Nicky is a typical example, then her complaint is really an understatement.

The wedding is produced, directed, scripted, edited, processed, publicized, advertised and distributed by MGM. The cameras click incessantly during the engagement, during the ceremony, and during the honeymoon. Seeing through the eyes of hundreds of cameras, millions of people everywhere—by means of photographs in their newspapers and magazines—share the couple’s intimate moments.

Liz takes a half-dozen pretty kitchen aprons along with her on their Riviera honeymoon. She probably has a dream of being a dutiful housewife to Nicky—cooking his meals, darning his socks, keeping his house. But she never gets a chance to take the pretty aprons out of the trunk. The marriage is a failure from the start.

Nicky stays up half the night gambling and sleeps half the day. Ed Sullivan’s daughter Betty, a bridesmaid at the wedding, runs into them in Europe and later reports, ”Once, I saw him come downstairs after he had gotten up in the afternoon, and Liz skipped across the lobby to throw her arms around him. He shrugged her off.” And always, wherever they go, the probing, merciless eye of the camera records the collapse of their marriage, the shattering of her dreams of innocence.

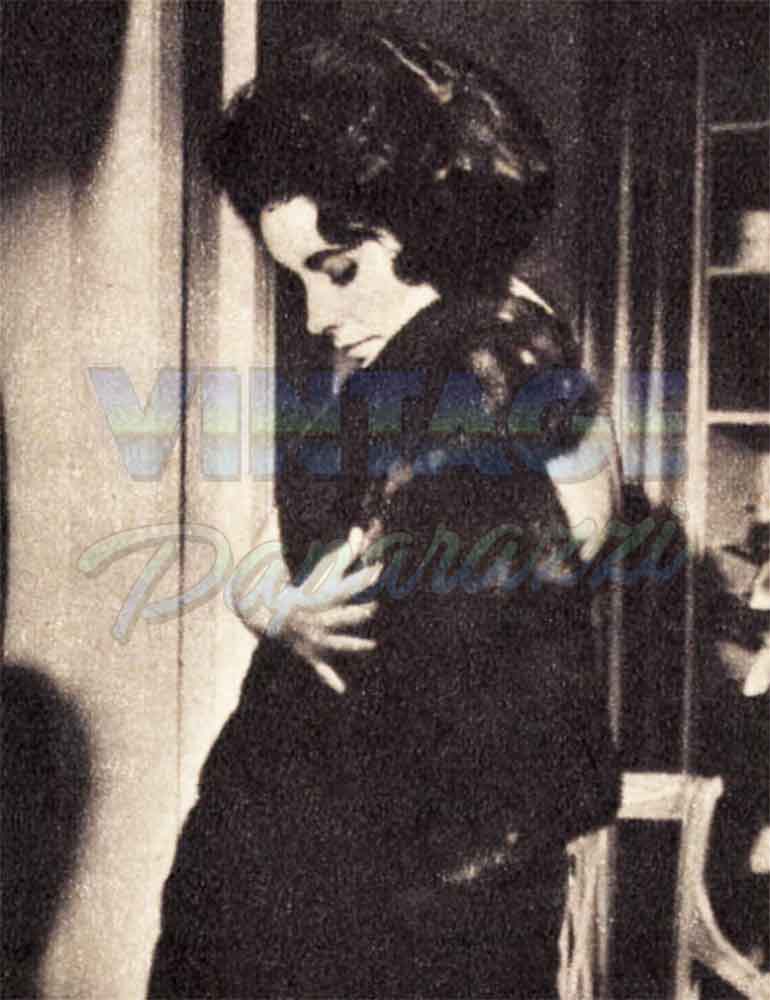

The camera eye blinks incessantly at her divorce eight months after her wedding. These are the first haunted and haunting pictures of Liz Taylor—the first of a whole series of such photos that will mark her torment and tragedy down through the years. An unbelievably beautiful face—but too thin, too pale, and much too sad for a girl who is still just 18.

Peter Rabbit is dead. Prince Charming is a delusion. Cinderella has nothing to believe in. Liz becomes a young gypsy, moving from friend’s house to friend’s house, searching for something she can’t put into words, running desperately away from the camera eye. The wear and tear on her body and mind during this hectic effort to discover herself is almost disastrous. She smokes cigarettes one after another, lighting a new one with the still burning butt of the last one. Her weight is dangerously low, 20 pounds less than when she got married. And she develops stomach cramps which are diagnosed as colitis. Colitis—a painful, frightening condition that lands her in the hospital and forces her to go on a strict diet of bland baby foods.

But even serious illness doesn’t protect her from the blinking eye. For her, ”privacy” is a meaningless word in the dictionary. Each gesture she makes is recorded on film and immediately passed on to the public. If someone had been able to steal her hospital X rays, they, too, would have been duly reproduced and printed for all to see.

”The trouble,” said Eddie Fisher many years later, ”is that people have always considered Elizabeth as a great star and a great actress and have given very little consideration to her as a human being.”

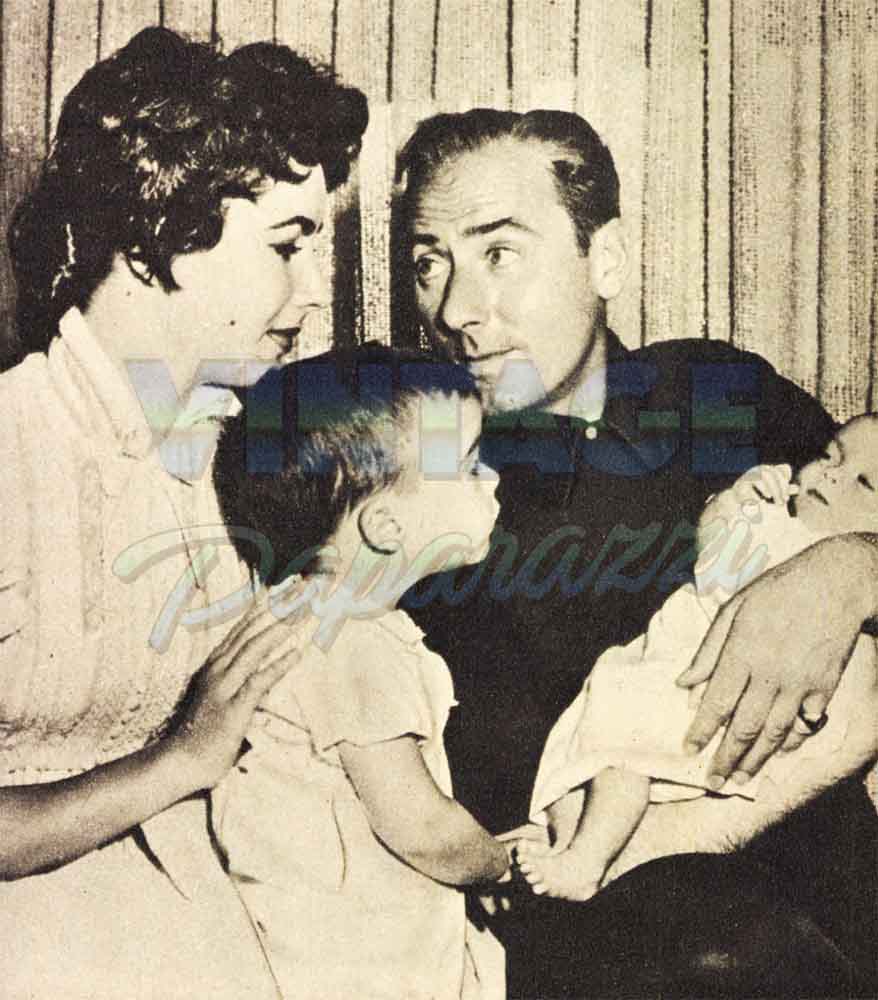

Her stomach trouble ceases and she throws away her baby food as soon as she meets Mike Wilding in London, in 1951. He is suave, he is sophisticated, he is handsome, and he is an ”older man”—20 years older, to be exact. When they are married in London’s Caxton Hall registry Office on February 21, 1952, a week before her twentieth birthday, the cameras are grinding and clinking away, and within a matter of hours the still photos of the wedding are on the front pages of newspapers throughout the world, and the newsreel pictures are in the Processing tank—and then on their way to the theaters everywhere.

Marriage for Liz Taylor and Mike Wilding is like living in a fish bowl in a store window. People are always looking in—not directly, of course, but through the eyes of the ever-present cameras. There is no escape. The price of fame, the price of beauty, the price of stardom is that you become public property. Not even Liz’ heart is her own.

The news of the birth of her first child, Michael, is splashed so thoroughly across the front pages of the newspapers of the world that one thinks, at first glance, that a Messiah has been born. It seems impossible that her second pregnancy and birth could command the same miles of newsprint, but they do. Every detail of the birth itself is made public, even to the fact that the obstetrician had, at her request, induced a birth, by Caesarean section, so that the baby would arrive on her twenty-third birthday.

When her marriage collapses, the cameras are there to photograph the ruins. And when a new Mike—Mike Todd—comes into her life, the public knows about it almost before Liz does herself.

”What Mike Todd did,” Liz Taylor has since said, ”was to teach me how to love.” But he did something even more important —he taught her how to laugh. To him, the clicking eye of the camera isn’t threatening; it is silly and funny, something to put up with. All they can do is record surfaces— superficial gestures, outward movement, meaningless expressions. Even an X-ray machine can’t capture the feelings and emotions within the human heart.

Mike’s energy, optimism and love overcome Liz’ doubts and fears. Life is a wonderful circus: He is the Ringmaster and she is the Queen. If she wants something, he snaps his whip and it is hers. If she says, ”I want the stars,” he has a fistful of them made for her—from diamonds that light up the darkness.

But even Mike, with the magic of love, can’t laugh away the evil eye of the camera eye forever. In December of 1956, two months before they are married, Liz is taken to Columbia-Presbyterian Medical Center in New York City and undergoes surgery for a herniated disc and spinal fusion—a condition that some people claim dates back to her fall from the horse when she was making National Velvet.

This is a dangerous operation, lasting several hours, with the horrible possibility always present that the patient may become permanently paralyzed. As a bone specialist comments shortly after the surgery, ”Even after proper healing in the spine, there is the danger that a sudden strain will cause herniated discs both above and below the old one.”

Yet, the demanding camera eye shows no concern for the seriousness of the situation. Cameramen try to sneak into the hospital and take pictures. One photographer rents a room in the vicinity of the hospital and trains his high-powered, long-range lenses on Liz’ private room.

To a world hungry for news, Liz isn’t a woman, she is a star.

When they are married on February 2, 1957, in an out-of-the-way Mexican village outside Acapulco, the camera eye is clicking away again. Mike can make stars out of diamonds, and millions of dollars out of faith in a picture, Around The World In 80 Days, but he can’t silence the click of the camera. Liz is in a painful brace. She can barely move. Yet, the camera records her every grimace, her every twinge of pain, her every crippled step.

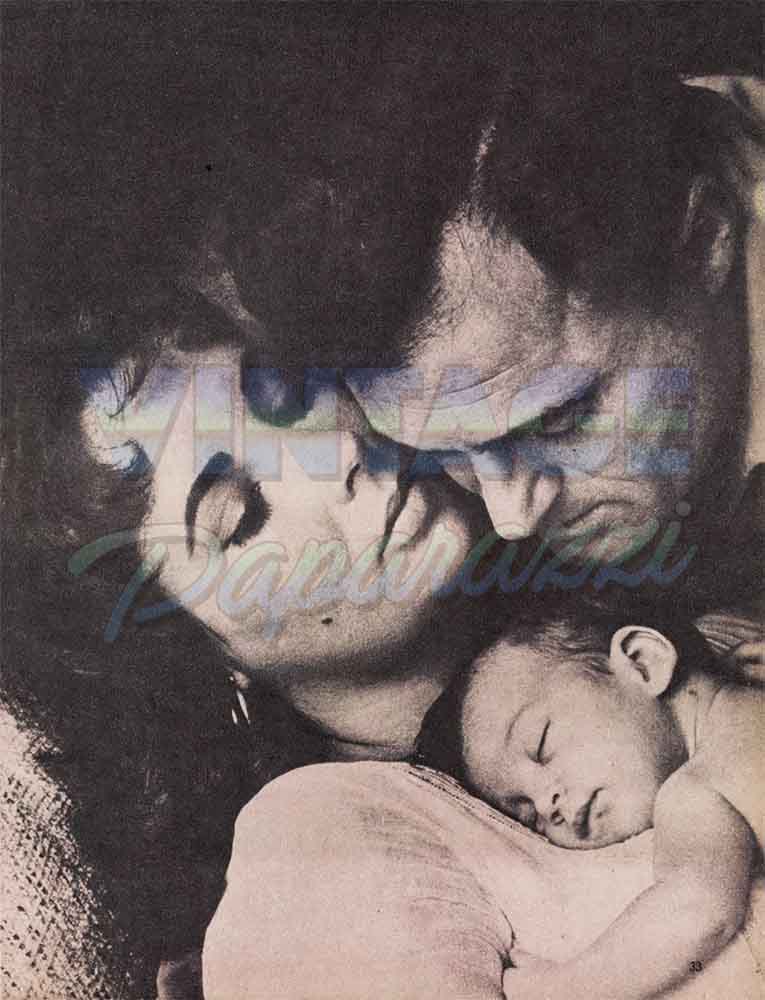

It is worse, much worse, when their daughter Liza is born prematurely. Words and pictures, pictures and words, deluge the United States and the rest of the world. Every intimate particular of the child’s struggle for life is passed on to the waiting public, like the latest episode of a soap opera serial. For 14 minutes, a resuscitator forces air into the lungs of the lifeless child, and Liz’ anxious fans learn all about those anxious 14 minutes before she does.

As the tiny baby finally breathes on her own and is being carried to a waiting incubator, Mike Todd is handed a note. He reads it quickly, curses and tears pour from his eyes. The note is a request from a photographer asking whether he can be the first one to ”take the baby’s picture.” Mike rips the note into a hundred pieces, but his tears don’t stop.

Ironically, it is a bad cold that is to save Liz from death. She is supposed to fly to New York with Mike on their private plane, ”The Lucky Liz,” but a 102-degree temperature keeps her at home. It is there, in the house they share together, that she receives the news that the plane has crashed in the mountains of New Mexico and her husband is dead.

With his death, part of her dies, too.

But the baleful camera eye respects neither Mike’s death nor Liz’ grief. It travels to the New Mexico mountains and photographs the mangled wreckage of ”The Lucky Liz.” It journeys to the funeral in Chicago and exposes her grief to the world as she weeps over his coffin. Thousands in the crowd surge forward on the cemetery grass, dropping candy wrappers, hot dog buns and ice cream sticks in their eagerness to get close to the helpless widow.

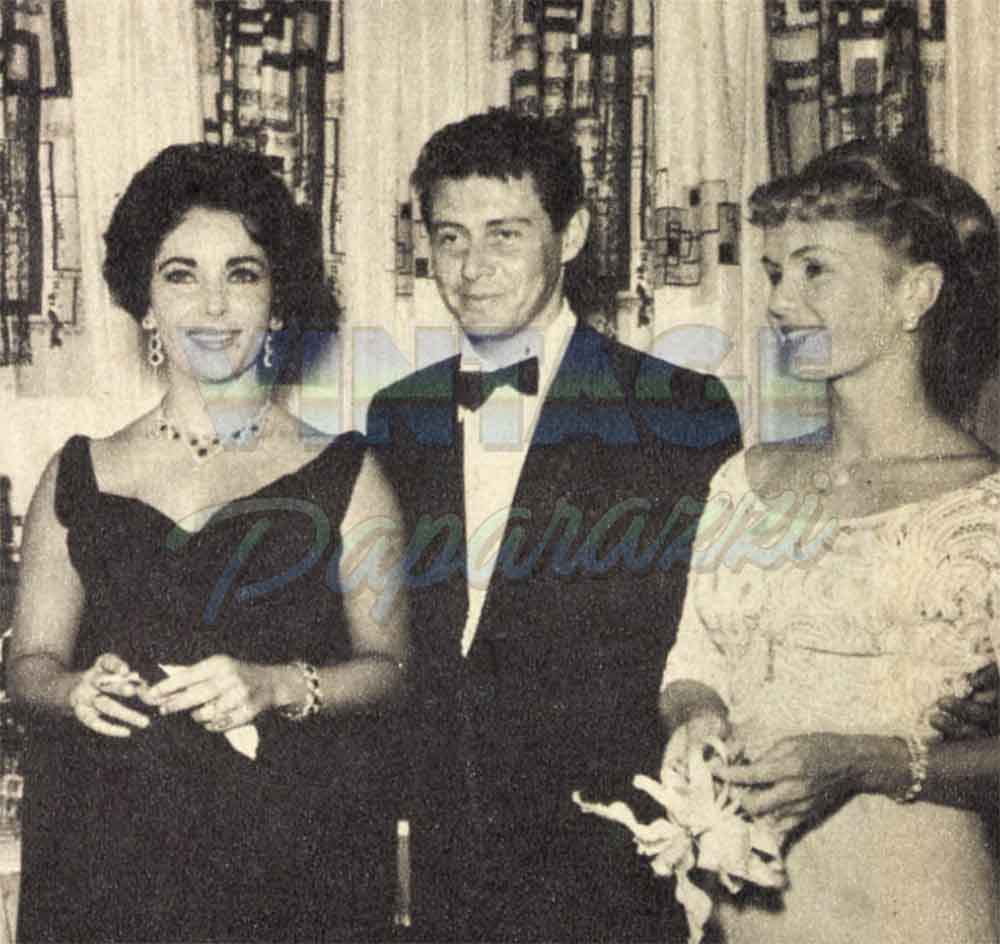

Worse is yet to come. The camera eye isn’t present that Labor-Day weekend of 1958 when Liz Taylor, Mike Todd’s widow, and Eddie Fisher, Mike Todd’s best friend, fall in love. But the crowd is. They eat dinner together in the main dining room at Grossinger’s, and almost 1,500 men and women slowly file past their table and stare.

When the news of their romance hits the headlines, the camera’s eye closes in on them again. It would seem that divorce was never known until the day Eddie Fisher divorces Debbie Reynolds, and that a widow had never loved again until the moment Liz Taylor falls in love with Eddie Fisher.

The cameras follow them everywhere. Photographers climb up the walls of her Hollywood home, try to bribe the guards to let them in, and wait through the day and night for some sign of Eddie or Liz. It doesn’t matter that Eddie swears his marriage to Debbie was finished even before he went out with Liz in New York. It doesn’t matter that Liz insists they sought each other out because of their mutual agony in the wake of Mike’s death, and that love came later—unexpectedly. The public, almost to a person, is shocked. And yet, the public demands photographs.

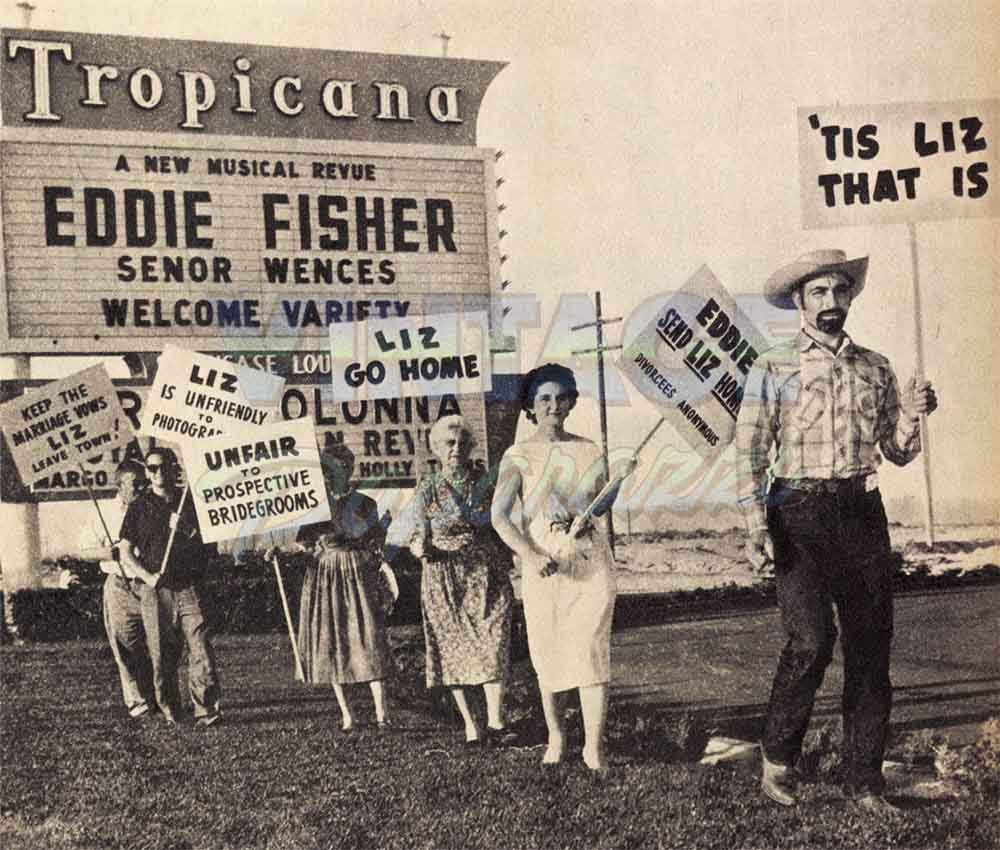

A star belongs in the heavens, bigger than life, better than life, and the public refuses to permit Liz Taylor to be human and capable of weakness and error. When Eddie and Liz go to Las Vegas, where he has a singing engagement, and she rents a ranch nearby, the camera eye follows. Again Liz is afraid to leave the house. And well she might be, for downtown, in front of the night club where Eddie is performing, a band of pickets march back and forth carrying crude signs—mostly directed at Liz, and shout accusations against both Liz and Eddie.

The cameras duly record the scene, and the signs—with their vulgar messages—are seen in newspapers in every state.

On May 12, 1959, the cameras click again. But this time, neither Liz nor Eddie care. They are too deliriously happy. On that day, Liz Taylor becomes Mrs. Eddie Fisher in a 15-minute ceremony in a Las Vegas synagogue. Her feelings toward him are summed up in the inscription on a watch she gives him after the wedding, “I love and need you with my life for the rest of time.”

But if anything, their marriage increases the public’s demand for more . . . and more . . . and more news about them. Whenever they leave their borrowed honeymoon yacht to go ashore for a few hours, the camera eye is waiting.

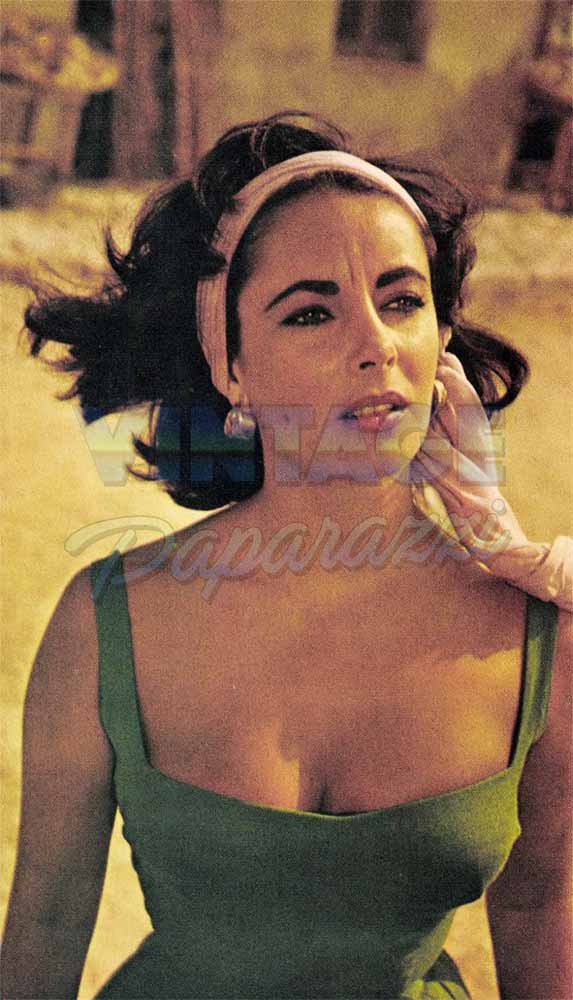

In June, the British press goes out of its way to attack them. In July, when they arrive in Paris, the Parisian papers take up where the British press left off. In Spain, in August, even when they try to hide in out-of-the- way Costa Brava near Bagur, the crowds discover them and come to gape and glare while they are picnicking or swimming.

It is the children—Michael and Christopher—who are terrorized by the camera eye in September. A swarm of reporters and photographers descend on them at the London Airport and begin firing questions and snapping pictures. It is Eddie who rushes over and rescues them.

Back in the U. S. in November, Eddie appears in a ”comeback” engagement at the Waldorf Astoria. Liz invites 70 friends to the opening night performance, and she picks up the check of $1,500. Eddie is a smash success that night and on the nights that follow.

But on Thanksgiving Day, they have little to be thankful for. Liz is rushed to the hospital with double pneumonia. She’d been suffering coughing fits and running a temperature ever since Eddie’s opening at the Waldorf, but she’d kept the facts to herself so as not to worry him.

Her condition, the doctors say, is critical. More difficulty in breathing than is normal even for pneumonia, more congestion than usual. In the days that follow, while Eddie commutes from the Waldorf to the Harkness Pavilion and spends the night in the room adjoining hers, Liz fights courageously against the deadly disease. And now, as in the past, the camera eye does not leave them alone.

Photographers hound Eddie, following him from hotel to hospital and from hospital to hotel. One cameraman demands to be allowed to take Liz’ picture, otherwise his paper will print an old picture of her in a hospital bed and claim it had just been taken. Eddie’s reply to this demand would have made Mike Todd proud of him.

When Liz walks out of the hospital on Eddie’s arm on December 13, the cameramen are lined up waiting for them. Weak and wan, Liz tries to smile. And the cameras keep clicking . . . clicking . . . clicking.

She is able to smile feebly that night early in April of 1960 when the Academy awards are announced. The year before she’d been nominated for Cat On A Hot Tin Roof, but the gossip raging about her and Eddie had turned public opinion against her, and she’d lost. Now, she’s been nominated for her role in Suddenly Last Summer, and is waiting in the audience of the Pantages Theater for the ”best actress” announcement. She holds her breath as the card is slipped out of the envelope, and then the name rings out, ”Simone Signoret.”

At that moment, the large red eye of the television camera is trained on her. The eye must be served; the public must have it’s ”good loser.” Liz Taylor smiles, a feeble smile at first, but then it widens and warms as the blinking eye moves in close. A star must twinkle, a star must shine, a star cannot be tarnished or dull.

In the fail of 1960, the eyes of the cameras close in on Liz again. She is in London to make Cleopatra and the picture is delayed again and again because of her illnesses. Every time she leaves the Dorchester Hotel to visit a doctor or go to the hospital, the photographers are waiting. And when she comes out of the doctor’s office or the hospital, they are still there. On November 13th, when she is taken out of the side entrance of the Dorchester—screaming in agony and holding her head in pain—and placed in an ambulance, no photographer is in sight. But by the time the ambulance arrives at the London Clinic, the camera eyes are blinking as she is carried into the hospital. And they are blinking again, days later, when she leaves after being cured of meningism.

Always the eye—the horrible eye . . . looking at her . . . looking at her . . . looking at her . . . as it has done thousands of times before. . . .

The nightmare repeats and repeats itself . . . only this time, we are back where we were at the beginning, and Liz is close to death. Outside, the photographer is waiting, hunting. Suddenly, there is a scuffling in the crowd. The photographer’s camera falls and smashes to the ground. The eye is broken.

Liz Taylor does not hear the crash. She hears nothing. Icy fingers reach out for her. She shudders. Her labored breathing becomes more irregular. The moment of grave crisis is at hand.

Then a miracle happens— beyond the understanding of Science, beyond the comprehension of mortal man. The cold fingers of death withdraw from her. The crisis is over. The word goes out—Elizabeth Taylor will live.

Eddie Fisher and Liz’ parents, Mr. and Mrs. Francis Taylor, thank God for His mercy. Liz’ friends hug each other and smile for the first time in days.

Out in the Street, the members of the crowd—quick to condemn and slow to for- give—shed tears of relief.

Liz begins her long, slow period of recuperation. The electronic lung is removed from her room. The tube is taken from her throat. She is finally able to tell Eddie out loud what she could only scribble on paper during the terrible hours of her pain and torment: ”I love you.”

The nightmare, for the moment, is ended —or so it seems. One camera has been smashed, but outside in front of the hospital other relentless, merciless eyes that never sleep are waiting. Soon the cameras will click . . . click . . . click once more, and the endless flight and the ceaseless pursuit will start all over again. That is the torment Liz Taylor can never escape.

—BY JIM HOFFMAN

It is a quote. MOTION PICTURE MAGAZINE JUNE 1961