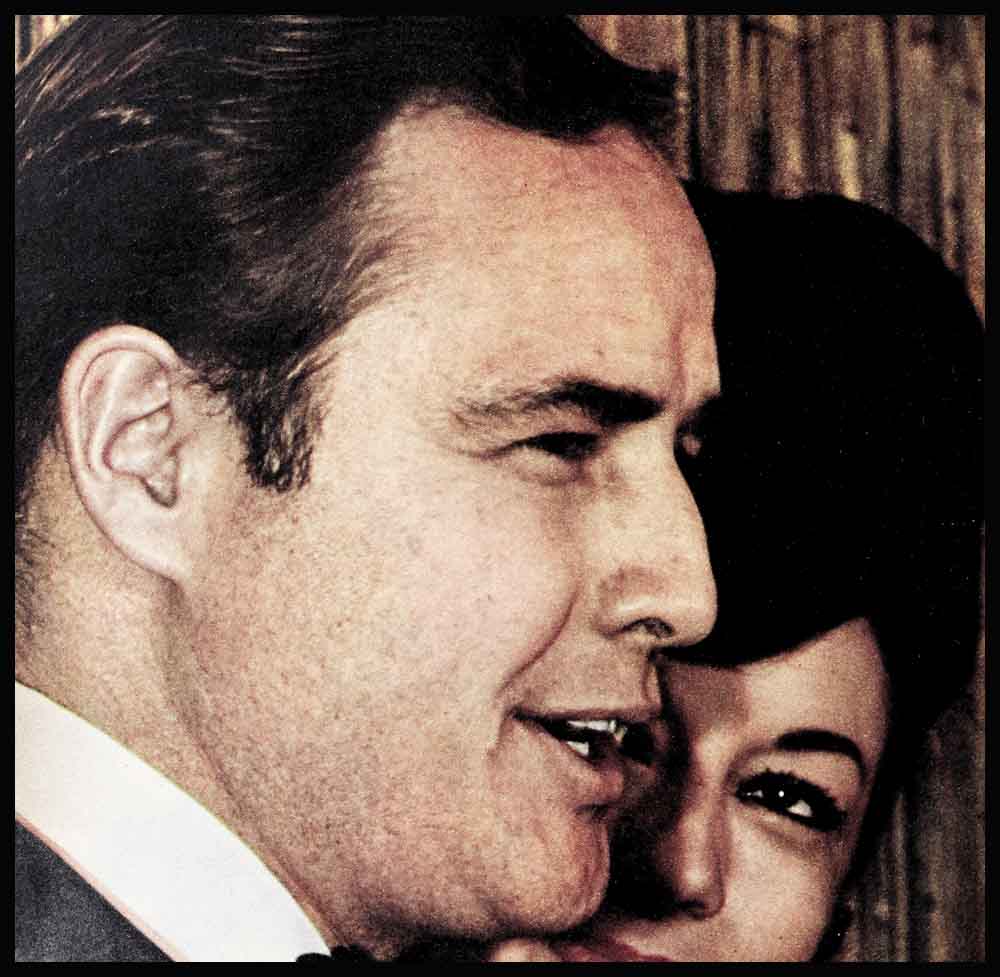

Marlon Brando’s $5,000,000 Why He Threw It!

For years Marlon Brando has borne the brunt of jokes, cracks and criticisms of his mumbling, his “Method” acting, his torn T-shirts—and he took it without so much as mumbling back at a single detractor. Perhaps he figured that this sort of thing made him into a legend—the Marlon Brando Personal Quirks legend—and that’s not bad for an actor.

But that was the old Brando. Now there’s a new Brando, and he’s changed his “sticks-and-stones-may-break-my-bones-but-words-can-never-hurt-me” attitude. Now Marlon has hauled off and thrown a five-million-dollar punch at the Saturday Evening Post—suing the magazine for a story he claims maligns his professional integrity. Having personal eccentricities, it would seem, is one thing to Brando. Being accused of professional delinquency is something quite different. And he isn’t taking it lying down.

As it happens—and prior to the suit filed in Los Angeles Superior Court this January—Marlon did break his silence long enough to expose a few of the more common legends about which he had been patiently mum these many years. Here are four which he terms arrant falsehoods:

Legend No. 1: Marlon tried to hide his parents.

Marlon’s refutation: “I’m anxious to tell you about my family because I want to blow sky-high the lies that have been told about them. Some people have spread it around that they were just a lot of no-goods. One columnist even said that the reason why I didn’t drink was because my father and mother were alcoholics. That’s a rotten thing to say.

“Even if it were true, it would be a rotten thing to spread around. But it isn’t true, it’s just a lie. Mom and Dad were no more than social drinkers—a cocktail before dinner, probably as many as two before a party. And that’s all.”

Legend No. 2: Marlon was born in poverty, a kid from the wrong side of the tracks.

Marlon’s refutation: “Maybe that’s the usual romance they spin about an actor. Well, I’m sorry to kill the Cinderella legend, but the truth is that we Brandos were what you would call ‘pretty well off.’ We lived in a nice house with five bedrooms and we always had enough of everything.”

Legend No. 3: Marlon was a rebel from the moment he learned to talk; his first word was undoubtedly “No.”

Marlon s refutation: “From high school I went on to the Shattuck Military School in Minnesota. I hated it so much that I didn’t stay the full course. Maybe that’s where the legend was born of Marlon Brando being an out-and-out rebel.”

Legend No. 4: Marlon was a bum; in fact for a while he’d actually been a hobo.

Marlon s refutation: “After Military School I dug ditches for two weeks. Perhaps the legend was born then . . . the one of ‘Marlon the Hobo.’ The truth is that the idea of strenuous open-air toil seemed attractive and grown-up, as it does to any sane and hearty youngster.”

But Brando’s point-by-point demolishment of these myths served only to inspire the myth-makers to still more fantastic ones. Helplessly, he lapsed back into silence, breaking it only occasionally with such cries of protest as, “Now in New York, people are really interested in acting as acting. But not in Hollywood. all they want to know here is about my girl friends and how many suits I have. This thing about jeans. I’ve grown sick and tired of that fake ‘Bum in Blue Jeans’ legend.”

Yet neither refutations, silences nor outbursts had any effect on the alleged liars; so Marlon, like a turtle avoiding attack, pulled his head completely into his shell and tried to ignore the press.

Jessica Tandy, the actress, once brought one of Hollywood’s most famous women reporters to Marlon’s dressing room. Brando, not knowing or not caring that this woman prided herself on her youthful appearance, although her youth was far behind her, said to Jessica, “Ah, this must be your mother.” Much later, Marlon denied that he was being boorish or wilfully cruel. “I admit that I did make a mistake with that writer. Jessica Tandy brought her to my dressing room in New York while we were doing ‘Streetcar,’ and I blurted out—before they got close enough for me to see clearly—‘Jess, your mother!’ I learned afterwards that the woman was very sensitive about her age, and she’s been angry about that ever since and thought I did it on purpose. But in the shadows, they did look alike.”

Then Katherine Hepburn, who had admired him on Broadway, asked to meet him. When they were introduced on the West Coast, Marlon’s sensitive antennae, always feeling out for real or imagined hostility, thought they detected a patronizing attitude.

“Who are you?” he blurted out. “And what do you do?”

Brando always defended his compulsive, sometimes brutal honesty by asserting, “I am myself, and if I have to hit my head against a brick wall to remain true to myself—I will do it.” And in truth it must be said that Marlon spared himself least of all in puncturing sham and hypocrisy with knives of truth. When he agreed to leave the Broadway stage to star in Hollywood’s “The Men,” he admitted, “The only reason I’m here is because I don’t have the moral strength to turn down the money.”

After he made the film version of “Streetcar” and played the lead in “Zapata,” he said to a friend, “I’ve been in three motion pictures. In the first I played a cripple, in the second I played a creep and in the third I played a kreplach. Every creep part that comes along, someone says: ‘This is just right for Brando.’ If I could crawl on all fours, they’d put my face on Lassie and write a part for me.”

Although many critics praised him for I his performance in “The Wild One,” Marlon stated, “The film was a failure. Instead of finding out why young people tend to bunch in groups that seek expression in violence, all we did was show the violence.”

Even his Academy Award winning acting in “On the Waterfront” did not satisfy him. “I was disappointed in it,” he said. “But as for standing up celery-straight and walking out—I did not.”

About “Desiree,” in which he portrayed Napoleon, he was equally outspoken. “Most of the time,” he confessed, “I just let the make-up play the part.”

Seldom pleases himself

His self-criticism of his acting in “Tea-house of the August Moon” was of the same pattern. “I’m not fully satisfied with my performance. I think the make-up helped considerably,” he said.

After completing “The Fugitive Kind,” he was asked whether he’d ever be willing to act with Anna Magnani again. “Only with a rock in my fist,” he mumbled.

He evaluated “One-Eyed Jacks,” in which he was both director and star, with the same uncompromising honesty. When asked about his opinion of the finished film, he countered with his own question: “Do you really think it matters?”

On another occasion, he was more direct: “I’m not pleased with the interpretation Paramount imposed on the story after they took me off it. I was over-budget by $1,500,000. Until then it was my picture, but when I went over-budget they had control.”

He gave “One-Eyed Jacks” the Brando kiss of death. “It’s a potboiler.”

Yet how could this man who was quick to expose the untruths of others and quicker still to demand complete honesty of himself, stand quietly by as a chorus of critics joined in accusing him of sabotaging “Mutiny on the Bounty”?

Perhaps a clue to his silence can be gained from listening to what his sister, Jocelyn Brando, has to say about him: “He so wants honesty in all his relationships that when someone is blatantly dishonest he’s so disappointed he can’t talk, he can’t cope with it, he’s too emotional.”

But defense of Brando’s behavior in “Mutiny” came from many places, both expected and unexpected; and soon some of the silliest charges against him were exploded.

The charge that he sulked on the set and interfered with the work of the director and the scriptwriters was blasted by “Mutiny’s” producer, Aaron Rosenberg. “Marlon gave us a rough time,” he said, “but he felt we were not living up to the agreements we had made with him about the basic concept of the picture. Besides, with a modern actor like him, he’s got to feel the part and you must allow him to make his contributions to the script and the directing. Otherwise he can’t work.”

Rosenberg’s statement is a variation of what two other motion picture greats have said about Marlon in the past. Actor Karl Malden said, “in an industry loaded with pressures—time, time, time and money, money money—Marlon goes about taking his time and caring nothing for cost. He lets nothing go by unless he feels it’s as good as he can get.” Director Elia Kazan said, “He gets inside a part and eats the heart right out of it till the part is him and he is the part.”

One charge, that he used ear plugs to shut out orders from the director and suggestions from the other players, was refuted by one of Marlon’s friends (as quoted by writer Hyman Goldberg) : “This is ridiculous, because Marlon always has kept plugs in his ears when studying a script. He has to concentrate completely, and he finds he can’t, with all the noise that is made on a set or on a location, when a camera shot is being set up. But, of course, when somebody speaks to him, or when he’s working, he takes the ear plugs out.”

The charge that he stayed up all night dancing barefoot with native Tahitian girls was put into its proper perspective by “Mutiny” cameraman Robert Surtees. After asserting that “People seem to prefer to read and believe the worst,” Surtees went on to declare, “but people don’t know that he brought his Tahitian cook’s two-year-old grandson back with him to California, kept the child at his home and had a surgeon correct his deformed foot.

Critics liked his “Mutiny”

The charge that he deliberately spoiled the film by making Fletcher Christian an unbelievably comic character was countered by the American movie critics, who almost to a man praised both Brando’s conception of the part and his actual performance. Cheered Archer Winsten of the N.Y. Post: “Brando comes in with an upperclass English accent that can stun an American with its eerie precision. Perhaps a Britisher could find a flaw, not this department. With these speeches Brando forever lays to rest the persistent ghost of Stanley Kowalski.” No one-accent man.

Applauded Kate Cameron of the N.Y. Daily News: “Brando’s performance is an arresting and deeply moving one. In the first part of the film, he displays a flair for comedy that has been missing in his screen appearances.”

The charge that he had come to blows with an extra and had been floored by a punch was proved to be false by columnist Louella Parsons. Wrote Miss Parsons: “I can testify that no matter what is said or printed—Brando says nothing in his own defense. Just recently I ran a story that during the shooting of added scenes for ‘Mutiny’ at M-G-M, an extra had become so annoyed with Marlon that the extra hit him and knocked him down.

“Say that about .any other star and I would have had everyone from the thespian to a lawyer on the telephone. It was quite by accident I heard the story of what actually had happened. The extra was quite drunk. all day long he had been going around throwing his arms around Marlon in an old palsy-walsy mood of intoxication. Then with a final lurch of good fellowship, he had flung himself so heavily on the star they both came down in a heap.

“But did I get this simple explanation from Marlon? Not on your life. It came in a letter from another player in the picture who said he was writing to me in the spirit of ‘fair play.’ ”

The charge that he checked neither his temperament nor his temper was put into its proper context by director Lewis Milestone, who replaced the original director, Sir Carol Reed, in mid-picture. “The big trouble was lack of guts by management at Metro,” Milestone said. “Lack of vision. When they realized there was so much trouble with the script they should have stopped the whole damned production. If they did not like Marlon’s behavior they should have told him that he must do what they wished or taken him out of the picture. But they just did not have the guts.”

Marlon’s side of it

Explanations and refutations from many people, but for a long, long time just silence from the accused, Marlon Brando! Then suddenly, in an amazing turnabout, he began to tell his side of the story—to Joe Hyams, to Dave Jampel, to a Newsweek reporter.

Why?

Not for his own sake; never just for that.

But because of what the gossips and the studio spokesmen and some columnists had done and were doing to others. To the memory of Marilyn Monroe, for instance. To Liz Taylor, for another.

Years before, Marlon had said, “Just because the big shots were nice to me, I saw no reason to overlook what they did to others and to ignore the fact that they normally behave with the hostility of ants at picnics.” Now his own protest was triggered by what “they” had done to Marilyn.

Speaking for Marilyn

“Do you remember when Marilyn Monroe died?” he asked. “Everybody stopped work, and you could see all that day the same expressions on their faces, the same thoughts, ‘How can a girl with success, fame, youth, money, beauty . . . how could she kill herself?’ Nobody could understand it, because those are the things that everybody wants, and they can’t believe that life wasn’t important to Marilyn Monroe or that her life was elsewhere. People have nothing in the lexicon of their own experience to know what fabulous success is—they don’t know the emptiness of it. . . . It’s a fraud and a gyp. It’s the biggest disappointment.”

In speaking for himself, therefore, he was in a sense speaking for Marilyn and for Liz. In fact, he asserted flatly that he and Liz have been made “scapegoats” in connection with high-budget films which were started without complete Scripts.

Brando’s refutation of the charges brought covered the following points:

On being a scapegoat: “Obviously the studio is going out after me to lay the blame for this fascinating saga of failure at my feet. From the beginning they’ve been blaming me and I’ve been the goat.”

On script trouble: “It was started with- out a script; that was the original sin. . . . If you send a multimillion dollar production to a place when, according to the precipitation records, it is in the worst time of the year, and when you send it without a script, it seems there is some kind of primitive mistake . . . The reason for all the big failures is the same—no script.”

On malingering: “I have never worked harder on a picture in all my life.”

On the “firing” of Sir Carol Reed: “Not only the actors, but the director and producer suffer. Carol Reed really suffered, perhaps more than us all. I know that he wasn’t fired. I was in the room. He quit. He said he couldn’t go any further.”

On studio behavior: “It’s all so simple. If an actor was working for me and got out of line, I’d get the Screen Actors Guild on the phone. They have the authority to punish actors. They’ve done it before.”

On the status of an actor: “An actor is a product like Florsheim shoes or Ford cars—he’s just generally exploited the way any other piece of merchandise is.”

On receiving one million dollars plus a half a million “overtime” for “Mutiny:” “It’s ridiculous!”

On the bright side: “There’s only one compensating feature in the year and a half I feel I must write off as an actor—I went to Tahiti.”

And he came back from Tahiti, and threw his five million-dollar punch at a magazine for printing a story he claimed was damaging. Marlon Brando finally hit back.

JIM HOFFMAN

See Marlon in U-I’s “The Ugly American” and M-G-M’s “Mutiny on the Bounty.”

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE MAY 1963