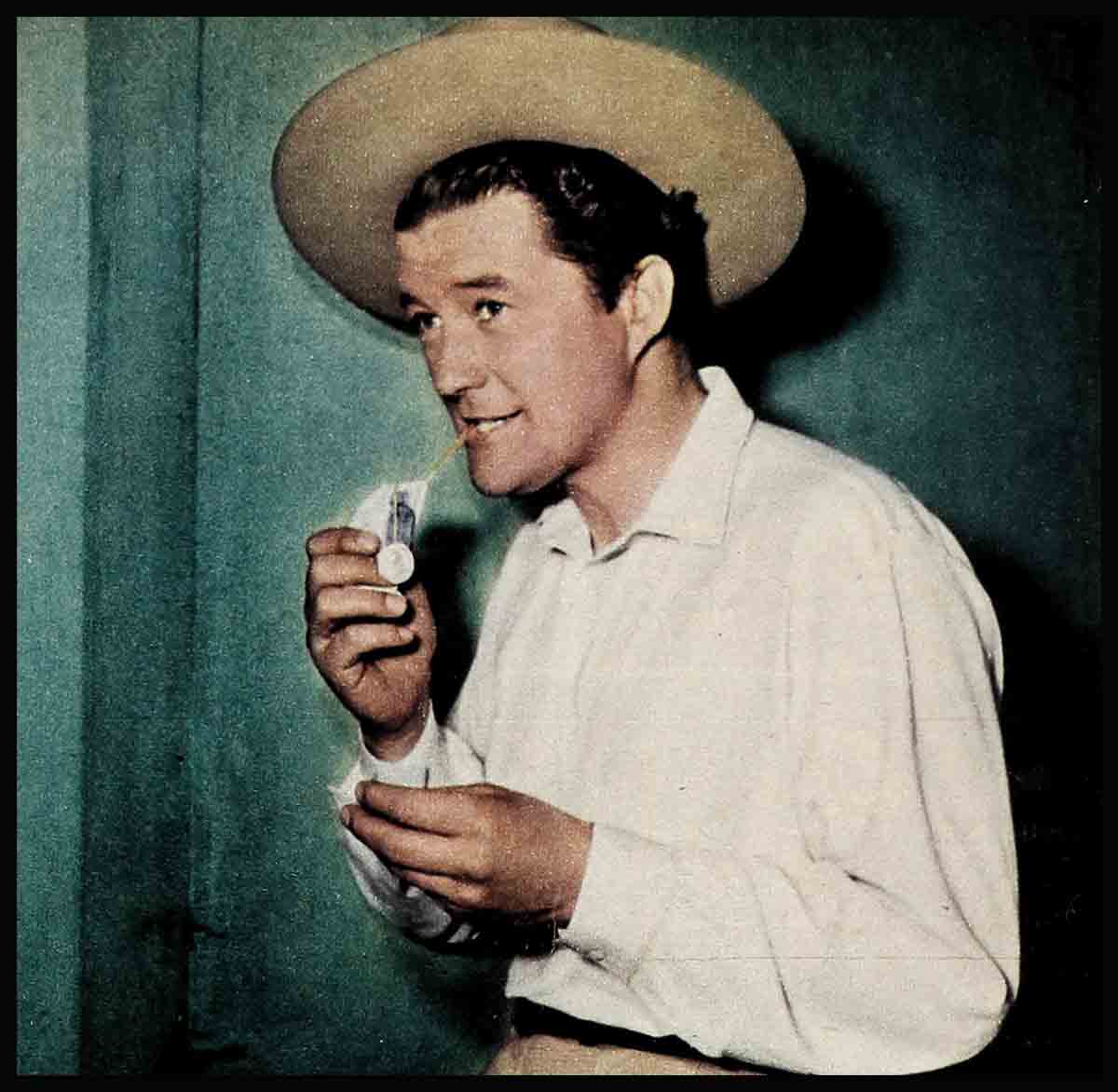

Tent Show—Dennis Morgan

The International Concert and Opera Company, purveyors of better times and bigger arias to the Midwestern states, was in a decidedly inharmonious mood. . . .

Professor Alexus Baas, who by coincidence sang bass, was wearing an expression lower than his deepest note. The fact that a slender brunette contralto and a curvesome blonde soprano rode with him on the jouncing floor of the Chewy truck did not keep him from staring savagely at the back of the driver.

“You should be handling a cement-mixer,” he said, addressing the back.

The driver, tenor extraordinary according to the local handbills, had a scowl on his handsome young face—a face that somehow managed to look pure Irish in spite of his Scandinavian, Scotch and Dutch ancestors. At nineteen years, Dennis Morgan, or Stanley Morner as he was named then, was not looking as far ahead as Hollywood. He was listening to the bouncing of five wardrobe trunks roped to the truck’s roof and praying they could make an immediate sixty miles in time for their next tent show. The show, had he but known it, that was to contain all the horrors a tent show could have. . . .

Across Wisconsin, through Michigan, over Illinois, past Indiana into Ohio—for five months the troupe had been Number Four attraction on the Central Chautauqua Circuit’s list of events. For those five months it had been his job to haul five trunks, the scenery, one male and three females. Dennis shuddered to think of what might have been his lot if he had a full-sized show-tent to haul from state to state. That, and five trunks and the scenery—and three females—!

Females, at this time in his life, were pretty generally divided into three classes. To begin with, there were the women he had left behind him. Mom, who had done some professional singing of her own, and sister Dotty who was at the excitable age, and girl-friend Lillian who actually belonged in a class by herself because someday he was going to marry her. He remembered their pride and emotion, packing his costumes and other theatrical equipment. Dotty, especially, squealing over his stage make-up—a large, round tin plainly labelled “Hero-flesh.” All three of them were back home in Park Falls, Wisconsin, now, imagining him hero-ing it right across the country. . . .

In a way, they were not too wrong—because class Number Two consisted of audience-females, with whom, he modestly admitted, he got along very well. Audiences on the whole, he had learned, varied so little from show to show one might almost think the population of one town had galloped on ahead to the next town. There were school girls who giggled and pointed out the actors—and the matronly ladies who sat under the hot canvas waving fans in front of their faces. They could be completely won over with one rendition of the Irish-tenor classic, “A Little Bit of Heaven.”

Class Number Three, female artists, whom you might expect to be different from other females—weren’t. They left make-up kits behind in hotel rooms, lost important parts of their music and fussed over a runner in their opera-length hose, and sometimes wore their hair in curlers while traveling. Slim, brunette contralto Dorothy, who’d gone to college with him; blonde, blue-eyed soprano Eloise, whom he sometimes suspected of crying for the home folks at night; and tall, redheaded Margaret, the pianist who now rode beside him, were all fine troupers. Trouble was, none of them could fix a tire. . . .

At this point in his thinking, the Chewy hit the front end of a culvert, leaped into the air and came down with a jar calculated to knock both O’s out of Ohio!

“L-Look behind—” gasped Dennis, grip- ping the wheel with white knuckles. “S-see if they’re still with us—”

“I—I can’t—” moaned Margaret. “You look.”

Turning his head slowly, he was just in time to see Alexus and the two girls settling down from the ceiling of the truck. One look, and he burst into laughter. They were completely coated with dust.

“You should see yourselves,” howled the driver. “What are you rehearsing for—mud pies?”

The professor usually showed a working knowledge of humor. Not now.

“We do not wish to see ourselves,” said Alexus in grim tones. “We will now ride up front. Pull over while we change.”

There was still some fifteen miles to go at top speed and the professor’s driving was even worse than Dennis’s. But they made it—with barely enough time to de-cake the dust, fall into their clothes and step out onto the rough pine-board stage before the heat-saturated spectators.

Afternoon performances were usually a build-up for the evening. The troupe gave forth with ballads and light concert airs—a mere taste of the full, albeit condensed, rendition of “Faust” which might be expected later. This particular afternoon the heat under the big canvas was more than ever oppressive. Some small boys sitting in the front rows, uncomfortable and sticky, were determined that someone should pay for it—and it might as well be the performers. They were armed with angelic expressions, a large bag of peanuts and unerring aims.

For the first time in the troupe’s history, “A Little Bit of Heaven” left the audience untransported. Following that, there was the matter of the peanut which lit on the stage just a minute ahead of contralto Dorothy. It was her custom to introduce her first song, the “Habanera” from “Carmen,” with a slight Spanish dance.

“Ah love, thou art a wilful, wild bird ” sang Dorothy, moving to the slow and sensuous tempo. “None thy wings may hope to ta-ame—” At this moment she suddenly left the tempo behind, gave a fast lurch forward as her foot lit on the rolling peanut. Followed a couple of skittish, bird-like hops, a ripping sound as one of her high-heeled Spanish “zapatos” caught in her hem—and with a dull thud Carmen landed on her flounces.

The little boys in the front row were, of course, wildly appreciative of this unscheduled entertainment. A few of the oldsters snickered, most of them, tsk, tsk-ed pityingly. Secretly, Dennis had always considered Dorothy a little stiff, even prim, in her impersonation of the seductive cigarette girl. Perhaps this jolt might put a little more abandon into her future num- bers. At the moment, however, he rushed forward to cover her humiliation, bursting into “My Wild Irish Rose.”

“ — the swe-etest flower that grows— You may look everywhe-ere— ”

This last phrase struck him fatefully He suddenly had a picture of himself, digging through the contents of his wardrobe trunk. It wouldn’t be there, the long black robe that he needed for the opening scene of tonight’s “Faust.” No need to look because the robe was hanging serenely back in a hotel room on the other side of Ohio.

What to do about the problem of the missing robe? Temporarily it was solved by borrowing a long black raincoat from a native who surrendered it reluctantly, since “it looked like rain.”

In the interlude between afternoon and evening, Dennis and Alexus ran through a short rehearsal of the duel scene. In his relief over the robe solution, Dennis went at the dueling with exuberance. Also with misfortune, because a howl rose from his opponent:

“My leg, my leg—varlet, you’ve stabbed me!” yelled Alexus. Too true, he had not only cut the leg but ripped a great tear in the professor’s red tights. The leg was bad enough, but the tights were tragic, being his only pair. Dorothy darned Mephistopheles’ s red limbs with bright green thread, the only color she had.

Night came finally. The heat now had an ominous, brooding quality. The air under the canvas hung still and dead as marsh water, yet seemed to surge with an underlying threat. The spectators sat in their seats as one huge, waiting mass, perspiration gathering on their faces.

On the stage, Dennis sweltered under the heavy rubber raincoat which the aged Faust was wearing that night as he sat in his laboratory mourning his lost youth.

“In vain, in vain do I long for my youth—” tenored the leading man through his gray beard.

“Look, Pop—Santa Claus—!” The exclamation, called by a young demon in front echoed through the house.

Dennis sang louder: “Another day, and yet another day. O Death, come in thy pity and bid the strife be over—”

It was a relief when Alexus appeared instead—even though Mephistopheles moved with a limp and a determination to keep the green gash on his leg out of sight.

At that moment the audience jumped at the sound of a sudden and terrifying onslaught on the tent’s roof. Rain—sudden, slashing, beating—“like wild horses hooves tearing at the canvas,” the professor afterwards described it. For a minute, after the startled crowd had settled, Dennis thought the storm might be a blessing. The tautness inside the tent was broken the spectators, with nothing to do now but wait out the weather, were ready to concentrate on the performers. So was the rain. . .

It developed that the tent’s roof contained several very bad leaks. The leaks had formed in a little cluster, all of them f splashing directly down on the stage. The blue tights, already sweat-dampened, were soon streaked with water. With horror, Dennis wondered if they would shrink—because, as it soon proved, this was to be the wettest “Faust” ever given. Mephisto, doing his demoniac dance in the tavern scene, slid half-way across the floor. Marguerite’s “Jewel Song” was distinguished by crystal drops added to her flaxen braids.

The walls of the tent were beginning to suck in and out like a bellows. The crowd of 800 stirred nervously. The quartette raised their voices louder. . . .

“Oh Night! draw around them thy curtain . . .” sang Mephistopheles, “Let naught waken alarm or misgivings ever—”

The Invocation became not sardonic, but serious, to Dennis as he looked to the ceiling and smothered an exclamation. The huge center pole of the tent, planted squarely in the midst of the spectator rows, was partially unloosed from the canvas—a real danger if someone in the audience should observe its whipping about. He had a mental picture of what panic inside the tent could mean. One startled scream could set people scrambling over seats to get out of the way of the pole, then people scrambling over people, children crying as they went down. He shuddered and sang louder.

“All hail, thou dwelling pure and lowly. . . .”

It was hard to keep his eyes away from the top of the pole, he must not draw other eyes to it. His Marguerite’seyes, especially, were much too expressive, they would be sure to widen with fear.

“Come with me, my love—” he implored, in full voice. “Don’t look at the leaks, dope, don’t look at the leaks—” he added sotto voce to an indignant Marguerite.

THE classic “Faust” was rapidly becoming a burlesque. Its leading man darted here and there on the stage, chased by his amazed and irritated co-performers, all of them slipping, sliding, dripping. He knew the responsibility he was taking. Should the pole actually fall, there would be people caught under it. It was possible the entire canvas would be dragged down with it, trapping 800 humans in a smothering mass. If there was fire, the wind would whip it into an instant fury.

Still, most of the crowd-tragedies of history had been brought on by the victims, themselves. He placed his faith and his prayer in the pole, instead. The condensed version of “Faust,” however, must be made to outlast the possibility of panic. He began repeating stanzas— singing phrases over and over—going back to the opening scenes At the piano Margaret stopped, stumbled, skipped here and there in the accompaniment, glaring at him with hatred. Soprano Eloise was almost in tears as she tried to save the show. There was that in the professor’s eyes that said that after this maniacal performance, the Morgan public career was over. And the audience had forgotten the howls of the wind to give vent to their own. They never expected to see anything like this again.

The International Concert and Opera Company left town the next morning, early and quietly. They hoped the village papers would forego any reviews of the opera in favor of the news that last night a tornado had aimed at, then veered away from, Ohio-ville.

Today, as Dennis Morgan sings Shure, a little bit of Heaven—” for Warner’s screen—biog of Chauncey Olcott, titled under that all-time clincher, “My Wild Irish Rose,” he remembers and laughs back at those early Chautauqua days. On Sundays, Margaret Otterson still accompanies him now at his favorite Hollywood church.

But his wife, Lillian Morgan, says she has never heard him sing Faust. He hasn’t forgotten his song of terror—the night the tent pole held out—and so did he.

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JANUARY 1947

No Comments