Gentleman’s Agreement—Gregory Peck

When the editors of MODERN SCREEN asked me to write about this picture and its star, I accepted, not only because I am enthusiastic about Gentleman’s Agreement, but because it gives me an opportunity to answer one form of criticism that is perennially leveled at Hollywood.

That criticism is that Hollywood fails to measure up to its social responsibilities. Hollywood, say its critics, is interested solely in making money. Those who do not have to wrestle with the actual making of pictures, or count their cost, may not realize how rarely an “idea” picture can be found that is also one people will want to see. A factor known as dramatic interest is often overlooked. But no film, however realistic or timely, can be sure of an audience without it.

“Gentleman’s Agreement,” I realized as soon as I had read it, was no mere plea or preachment. If it hadn’t been dramatic, frankly, I wouldn’t have bought it.

Take the picture, Boomerang, which we recently produced at Twentieth Century-Fox. It contained an indictment of injustice in the United States. But if Dana Andrews had stood up in the courtroom and made a long, impassioned plea for justice while holding his wife’s hand, nobody in the movie theaters would have stayed to hear him. The dramatic impact of the scene is what held them.

During the war, I made a picture based on the life of Woodrow Wilson. It was the most expensive picture I had ever made. It was carefully produced, lavishly mounted, excellently acted. Technically, I still consider it my finest production. But Wilson was a “failure.” Not because it failed as an artistic achievement, for the fact is that the critics praised it. But it failed to carry the “idea” where it was designed to carry it—to all of the people. Therefore, in my final estimation, Wilson missed the boat.

I do not think Gentleman’s Agreement will fail, and I am not speaking only of box-office returns. There must be stories which come to grips with reality, if Hollywood is. to continue as a constructive influence.

I have children growing up and I, for one, am not prepared to face them one day and hear them say, “You had the eyes and ears of millions. They were looking to you to help make this world a better place—and what did you do with your opportunity?”

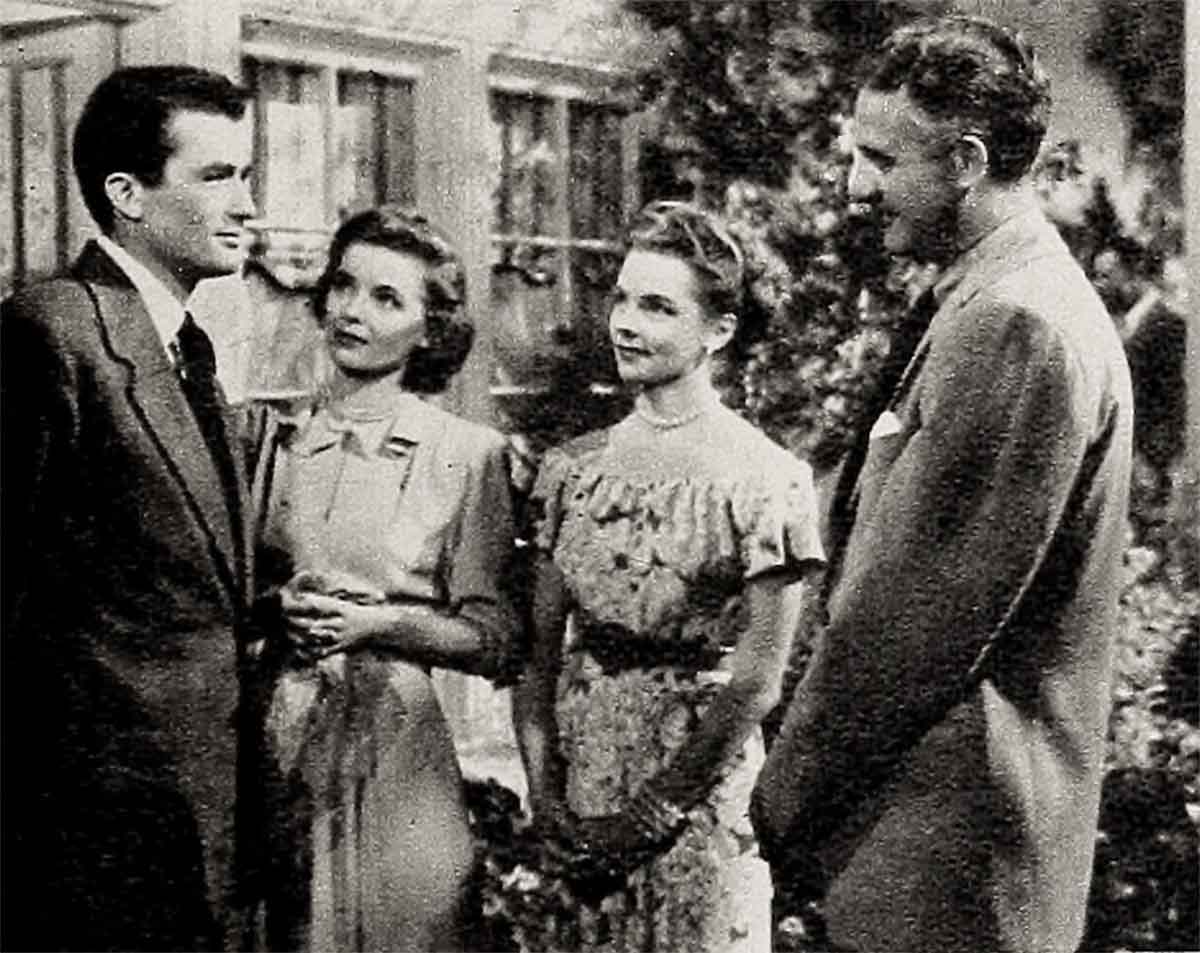

That’s a question that I will be proud to answer by citing Gentleman’s Agreement. This picture tells of an idealistic, courageous reporter who undertakes an assignment for a series of magazine articles exposing the ugly roots of antiSemitism in America. To get his story he poses as a Jew, although a Gentile, and by so doing discovers that his whole life is changed. The affections of his sweetheart are subtly affected, the happiness of his small son by a previous marriage, the attitudes of his friends; he even uncovers a hot-bed of prejudice on the staff of his own magazine.

There are many reasons why Gregory Peck came to mind at once as I read the first proofs of this unusual story.

My hero had to be far from the pretty-boy type. He had to be manly, with substance and intellect and background. He had to have a face that could be either Jewish or Gentile, convincing enough by his very. looks to be able to say, “I’m Jewish” and be believed, or “I’m not,” and still be believed. I, myself, don’t believe there is a pronounced Jewish “type” in the world, a fact which I’ve seen proven time and again.

Many of my friends and associates are of Jewish faith, but I had never thought much about anti-Semitism until I went to North Africa on army duty during the war. Occasionally, when I arrived at a new post I noticed a standoffishness among some of the officers with whom I worked. Later, they would come up to me, wreathed in smiles, shake my hand and say, “Why didn’t you tell us you aren’t Jewish?” It appalled me. I couldn’t see what difference that made, first of all, but what struck me was—they had no idea whether I looked like a Jew or Gentile My name merely sounded as if it might be Jewish.

Aside from the ambiguity of his features, the chief reason Gregory Peck fitted so ideally into the part of “Phil Green” is that he exemplifies sincerity, utter honesty and integrity in his acting personality. No man could play the star of Gentleman’s Agreement without such qualities.

The first time I ever saw Gregory Peck was in a Broadway play. Not long afterward, I trusted him with the role of “Father Chisholm” in The Keys of the Kingdom, the inspirational picture to which I was then devoting all my attention. Like Gentleman’s Agreement, The Keys of the Kingdom was an idealistic story, extolling service to humanity. Like the hero of Gentleman’s Agreement also, Father Chisholm, who left a pleasant clerical berth in Scotland to dedicate his life to missionary work in the interior of China, had to be played with the greatest conviction and sincerity, else the picture would have failed. It didn’t fail, either as a picture or as the role that launched Gregory Peck as a star.

no tricks of the trade . . .

Gregory Peck has no technical acting tricks, no polished, sure-fire techniques with which great names of stage and screen have often been associated. But his very lack of tricks endows him with a force far more important. In every part he has played, he has been entirely believable.

The responsibility he feels for the’ parts he undertakes, is a producer’s best insurance that they will be successful. He will turn down the most sought-after part in the most prized production of the Hollywood season—if he doesn’t think he can do it justice.

I remember an instance where he was enthusiastic about a story I had bought. It had a fine part for an actor, and I offered it to him but he turned it down. “It hurts me more than it does you,” he grinned, “but it isn’t for me.” He may have been right—who knows? The picture turned out to be a successful one. The part was excellent for another star. In my mind it was excellent for Gregory Peck, but I knew him too well to try to persuade him, and I gained new respect for his honesty.

So there was a certain amount of suspense for me as to whether or not Gregory Peck would play Gentleman’s Agreement. He might, for some reason, conclude that he wouldn’t fit.

I had already been fortunate in securing Moss Hart, the celebrated Broadway dramatist, to write the screenplay. Hart was challenged by this same story, and agreed to write a Hollywood scenario of something not his own, for the first time in his career. It meant, I knew, giving up a vacation and abandoning plans for a Broadway play. I had also secured Elia Kazan, the director who did such masterly jobs with A Tree Grows in Brooklyn and Boomerang. Kazan was enthusiastic about directing Gentleman’s Agreement. I sounded out both of them on Gregory Peck for the starring role, and they agreed that he was an ideal choice.

backstage story . . .

After returning from Sun Valley, I took the proofs of “Gentleman’s Agreement” to the theater where I was scheduled to receive an award for The Razor’s Edge. I knew Gregory Peck was on the same program, accepting an award for his performance in The Yearling. Backstage, after the show was over, I handed him the galleys. “Read these,” I suggested, “and let me know what you think about the story.”

If Peck thought himself right to play the part, he would take it. I figured he would, and I was right. He had been calling, my secretary informed me, all morning. He called again. He had stayed up all night—just as I had on the train—to finish the story. “I’ve never been so excited about any role in my life,” he told me. “It’s an honor to be considered, and I can’t wait to do it.”

So he is doing it—and with that attitude, knowing Gregory Peck, I don’t think I’m too rash in predicting hell make another bid for an Academy Award next year. You’ll see for yourself!

THE END

—BY DARRYL ZANUCK

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE DECEMBER 1947