His World Of Love—Rory Calhoun & Lita Baron

For four years, while she didn’t know he existed, Rory carried with him the memory of Lita’s face. To call it love would be unrealistic nonsense. Outside of some character in a fairytale, who falls in love with a girl he’s never talked to and never expects to set eyes on again? Nobody, including Calhoun. On the other hand, neither did he ever forget her.

It happened in ’43. Young Timothy Durgin worked at a logging camp. “Let’s go to San José,” said a fellow-logger. “I want to hear Cugat’s band.”

“Uh-uh. I don’t dance.”

“Then come along for the ride.”

In itself, the ride was something to remember. Since his pal’s 1918 Harley-Davidson boasted no buddy-seat, Tim straddled the fender, arriving with jolted bones and a corrugated rear, wondering why he’d agreed to this form of self-torture, dreading the ride back.

The ride back, however, proved painless, for his mind was on the girl who’d sung with Coogie’s band—a creamy-skinned little brunette dazzler in a white sheath gown. Yet it wasn’t her beauty that had moved him so much as a quality half glimpsed, half sensed—an almost childlike purity of feature, a kindness in the dark eyes, a sweet warmth in the smile, a dignity of bearing. Despite his teen-age tussles with the law—or even because of them—he’d developed a sure instinct for true metal in people. He felt it in this girl. He never expected to see her again but her memory stayed fragrant.

A year later he was Rory Calhoun of Hollywood. That story’s been told. How, on vacation, he visited his grandmother in Los Angeles and went riding in the hills. How he bumped into Alan Ladd. How they stopped to talk. How Alan asked: “Are you an actor? Well, you ought to be,” and took him home to meet Sue. How he wound up under contract to David Selznick.

Selznick believed in signing and training personalities. He produced few pictures. Working here and there on loanout, Rory failed to make much of a dent. He grew increasingly restive, increasingly certain that Hollywood wasn’t for him. His was the outdoor world he’d loved and left. He clamored for release. “Let’s tear up the contract. I want to go back to the hills.”

“No,” said his boss.

“What good am I to you? I’m not doing a thing.”

“Have patience. You will.”

“When?”

“When you’ve learned to act.”

“That’ll be the day,” groaned Rory, stomping off in defeat.

By ’47 the scene had changed. Idol of the bobbysoxers now, his stock was rising. He continued to feel more at home in the woods, whither he repaired whenever possible with his boon companions, Guy Madison and Howard Hill, the archer. But at least he no longer felt useless in Hollywood.

By ’47 he’d also learned to dance. One night he took a girl to Le Pavillon, a supper club that featured a rumba band, led by someone billed simply as Isabelita. Unaware, he walked in with his date. Unaware, he glanced at the dais—and there, unbelievably, she stood. Instead of singing with Coogie, she had a band of her own. Instead of the white sheath, her gown glittered with sequins. But the eyes and the smile, the grace and the dignity remained exactly as he’d remembered them. “Well, well, well,” he said to himself, while his heart stirred with a strange perception of fate. For that was the moment when Rory took his resolve. “I must get to know her. If I’ve made a mistake, I’ll clear out. If she’s what I think, this is it.”

The campaign

He plotted his early campaign along ‘simple lines. Every night for six weeks—including New Year’s Eve—he went to Le Pavillon, always with a girl. Over her head as they danced he watched Isabelita.

She could hardly help being conscious of him. Night after night he towered above the crowd—with the curly black hair and the widow’s peak, with the eyes whose color had earned him the nickname of Smoky, with the lashes no man had a right to. (“They’re to keep the dust out,” he assured her later.) She noted and liked his attentiveness to the girls he’d escorted. She noted, too, that the smoke-blue eyes were frequently turned on her, yet never in any discourtesy to his guest. “He’s not flirting exactly,” she decided. “Just trying to be charming.” Possibly in acknowledgment of this feat, she once said, “Good evening,” striking Rory dumb. If he made any response, which he doubts, it must have sounded something like buh-buh-buh.

From Le Pavillon she moved to the Mocambo. Rory moved with her. Again taking a girl. For the first week. But at length dawned a day when Calhoun addressed himself sternly. “You’re twenty-six, brother. Stand or fall on your own.”

That night he went to the Mocambo solo. But not without a friend at court. Johnny, one of the waiters, alert and romantic, had allied himself to the cause of young love. With no wastage of words between them, Rory knew it. “Give me a table near the bandstand, Johnny. So she has to pass me.”

Greg Bautzer, with the same idea, was there ahead of him. His table was closer to the bandstand—an advantage Rory took philosphically. Nice guy, Bautzer—a guy who showed excellent taste. Rory countered by ordering a magnum of champagne. As far as he was concerned, you could take all the champagne in France and dump it into the Seine. But it looked festive. It gave his table a flourish.

Lita’s rumba band alternated with Eddie Oliver’s American band. Her turn over, she stepped down and walked by Bautzer’s table. “Hello, Isa—” (pronounced Eessa in the Spanish way).

“Good evening, Mr. Bautzer—,” and on he went—toward the widow’s peak and he black hair and the lashes.

Johnny Cupid, hovering unobtrusively, tepped forward. “Isa. I’d like you to meet Rory Calhoun.”

He was on his feet. “Won’t you sit own?”

“I don’t sit with the customers.”

“Please? Just for a minute?”

She’d never broken her rule. In her own words: “I never let myself fall for something I didn’t know was going to be mine.” But at close range she found the blue eyes oddly—and if the truth be told—sweetly disturbing. Almost against her will she eard herself say: “Well, for a minute.”

He seated her. He seated himself. He said: “Will you have some champagne?”

“I don’t drink.”

“Neither do I. But here it is. We’ve got to do something with it.”

He poured a glass for each. In courtesy, she took a sip. Soon they were chatting away. But it wasn’t a twosome for long. Refusing to be left stranded, Bautzer turned from his table and chatted with them. His stint done, Eddie Oliver spotted the champagne and hied himself over. Lita rose to rejoin her band. “Please come back,” begged Rory. And she did. Meanwhile, between them, Bautzer and Oliver polished off the magnum. “If I’d known,” grinned their host, “I’d have ordered a gallon of milk.”

The evening wore on. The crowd thinned out. Helpful Johnny kept asking Bautzer if he’d like his check now. Either sleepy or discouraged or both, Mr. B. departed—and Lita fractured another of her rules. She danced with Rory, rationalizing her singular conduct to herself. “After all, we’re not really strangers. Our eyes have met so often across a smoke-filled room. And he’s not a wolf. I can tell from the way he talks. And I’ve watched him dance with all those other girls, so I just want to see how it feels to dance with him.”

Into the midst of this logic Rory plopped a question. “How do you get home?”

“My brother calls for me.”

“Couldn’t you tell him not to? And let me take you home?”

What excuses she conjured up to topple precedent again, Lita no longer remembers. Suffice it that Rory drove her home in his brand-new Studebaker. But not straight home. They paused at half a dozen drive-ins. For hamburgers. For pie a la mode. For coffee and more coffee and another cup of coffee. He was the hungriest kid she’d ever met up with—and the gayest. Neither a caldron of coffee nor one glass of champagne could account for the fact that every so often he’d stick his head through the window and give out with the Woody-Wood-pecker hoot. “Oh-ahhah-haaaah!”

One kiss??

Having scored on all fronts that evening, Rory lost on the last. Once parked in the driveway, Lita’s movements were brisk and unmistakable. Out of the car she hopped and up the porch steps, unlocked the door, went in, pulled it half shut and spoke through the aperture. “Good night and thank you.”

“Good night and thank you,” said the mannerly Mr. Calhoun.

She closed the door and leaned against it for a moment. Here was a boy she wanted to see again. If you want to see him again, you don’t make it too easy. You don’t let him kiss you first thing . . .

For a month she neither saw nor heard from him, which left her with mixed feelings. Disappointment. “Such an eager beaver all those weeks. Now not even a call.” Uncertainty. “Maybe I should have let him kiss me.” Indignant resolve. “They told me about actors. Just forget him, Lita.”

What she couldn’t know, since he hadn’t informed her, was that Rory had started working next day. When he worked, he didn’t date. That, however, was only half the story. Still mapping his strategy, it occurred to him that a touch of caginess at this point might do him no harm. His job done and his wages paid, he phoned her one day. “This is me,” he announced.

“Who is me?”

“Rory Calhoun.”

“Oh—”

“I’ve been on a picture.”

“Out of town?”

“Yes. But I’ve come in every night.”

“You could have called me.”

“I could have,” he conceded. Pause. “When’s your night off?”

“Monday.”

“Will you have dinner with me?”

As punishment, she should have turned him down. Or anyway, played hard to get. But she felt not the faintest inclination to punish either him or herself. “All right.”

“I’ll pick you up at 6.”

He was there at five of. Mama Castro fed him coffee till Lita finally appeared at 7:30. That’s according to Rory. According to Lita, he exaggerates. Whatever the hour, he started driving up the coast. And drove and drove. “Are you kidnaping me?” she demanded. “Where is this dinner?”

“At the Colonial House.”

Since the Colonial House sits fifty miles from Hollywood, they arrived hungry. The dinner was fine. Only over-social. Three wandering violinists who’d once played with Lita’s band hung around all evening. To compensate, Rory took the long road home. This time she invited him in. “Progress,” he thought happily—and entered to find himself facing a panel of sorts. There stood the whole family, lined up and waiting. Papa acted as spokesman. Bred in the patriarchal tradition, he sounded rugged. “How come you bring my daughter home so late?”

Rory’s heart sank. He wanted Pop to like him. If things turned out right, Pop might be his father-in-law. “I’m sorry,” he said. “I didn’t realize the time. We went to Oxnard for dinner.”

“Oxnard?!!” roared Pop, as one might roar Outer Mongolia!

“I brought her home late,” said Rory, “but I brought her home safe.”

His sincerity was patent. Pop allowed himself to be appeased. The family evaporated and Lita produced some Tony Martin records. Rory noted that they’d been autographed to her, which made him feel not so hot. They listened to the records, after which Lita rose. “I must go to bed now. Good night.” Again a dry run. No kiss. No nothing.

It came after an evening of dancing. He’d seen her home. “Let me kiss you good night,” he whispered. She slipped into his arms and stayed there a good ten minutes. It was worth waiting for.

A new world

They began going out together. He borrowed Guy Madison’s jeep and took her on picnics. Busy all her young life with singing and dancing lessons, she found his woodland world fresh and enchanting. He taught her how to be quiet in the forest, so they could watch the deer come down to drink. He taught her how to use the bow.

“But not to kill,” said Lita.

“A sportsman,” he explained, “never kills what he can’t eat.”

“I know. Still I cannot bear to kill and I will not.”

He learned she was all he’d dreamed and more. Little by little out came the story of his boyhood—the thefts, the prison record. “Sure, sure,” she laughed at first, convinced he was kidding, since kidding is as native to Rory as the breath he draws. Nor could she reconcile the bizarre tale with the man she knew him to be. But Rory didn’t laugh. Rory, she finally realized, was telling the sober truth. It was then that he plumbed the depths of her compassionate understanding. Her heart yearned toward the boy who’d paid and maybe overpaid for his mistakes. Through suffering he’d grown into strength and bedrock honesty. Except for its pain and its lesson, the past was past. He’d absorbed the lesson. She wanted to make up to him for the pain.

The months moved into August, and Lita faced a dilemma. Professional commitments awaited her in the east. Deeply in love now, Rory meant more to her than her career. That he was in love, too, she could hardly doubt. Yet he left the big question unasked. What ailed the man? Didn’t he know she must either keep or cancel those eastern engagements?

All right, it was Leap Year. In Leap Year a girl has the right to nudge. Lita’s not an aggresive type. Nudging came hard, but as they drove home one night, she made it. In a small voice. “Where,” she inquired, “is all this leading to?”

He parked the car carefully like a piece of glass. His big hands swallowed hers. “It’s all leading to matrimony,” he said gently. “I’d like you to marry me, Lita. If you’ll have me.”

“When?”

“Soon.”

On proposal night you ought to feel rapturous. Lita’s rapture was alloyed. Her problem remained unsolved. Soon can mean anything—next week, next month, next year. Soon can leave you up in the air, especially with fifteen singing dates to meet. Parting on that indefinite soon, Lita felt a little lost, a little woebegone. Sadness tinged her voice when Rory called back to tell her good night again. “Darling,” he said, “we both have birthdays in August. How about August? On the 29th?”

“Darling, the 29th will be lovely,” she lilted, all sorrow gone.

She canceled her dates. They arranged for the blood tests, the license, the church in Santa Barbara. But Rory had one more river to cross. “You’ll have to talk to my father,” said Lita.

“What for? I’m not marrying him.”

“It’s an old Spanish custom,” Pete explained. Lita’s brother was their confidant. “The old man,” he continued, “figures the whole bit. You wine him, you dine him, you ask for his daughter’s hand in marriage.”

“I don’t want to talk to him. You talk to him.”

Pete obliged by preparing the ground and reported back. “He still thinks you should ask him.”

Formality isn’t up Rory’s alley. Moreover, he was scared. When he’s scared, he takes the bull by the horns. Instead of asking Pop, he told him, making sure that Pete was around for moral support. “Lita and I are getting married in Santa Barbara Sunday. I thought you’d like to know in case you want to be there.”

“Hm,” said Pop. “Don’t you think you should wait a while?”

This was Pete’s cue and he picked it up nobly. “What for? They’re in love. Why waste good time? It’s next Sunday and that’s it. Come on, let’s go.”

Against two such stalwarts Pop didn’t stand a chance. Shrugging one of those all expressive Latin shrugs, he threw in the towel. “Okay. Let’s go.”

To seal their troth, Rory gave Lita a heavy gold-link bracelet with a heart-shaped medallion, whose inscription read: “May we live as long as we love and love as long as we live.” She gave him a watch inscribed: “Yours forever. Isabelita. August 29, 1948.” Only their families attended the ceremony at All Saints Episcopal Church. Rory’s mother, dad and two cousins. Lita’s parents, two sisters, two brothers. She wore a blue-gray sheath with an overskirt of gossamer Chantilly lace, and a Juliet cap. He was nervous, his bride having shown up a half hour late. Nervousness. makes him loud. In the quiet church, his response boomed. Lita’s voice you could barely hear. They exchanged matching. gold bands, plain and very wide.

“I didn’t want there to be any mistake,” says Rory. “I wanted a ring that looked like a wedding ring.”

For a while after the honeymoon they lived in Rory’s bachelor apartment, then moved to Ojai by grace of Lita’s folks. It happened this way. Rory’s grandfather had died intestate, leaving a ten-acre ranch which the grandson craved. But he hadn’t the wherewithal to acquire it. Mom and Pop Castro put their heads together and came up with an answer. For love of Rory, they’d buy his grandfather’s ranch. “If you and Lita will move in with us,” they said—

To a gesture so warm and spontaneous, what can a man do but give thanks? For two years they made their home with the Castros—till, twenty miles over the mountain, they bought Rocking Star Ranch for themselves. When work called Rory to town, they stayed at hotels—which proved expensive. “In the end,” said Lita, “a house would be cheaper.”

“A house,” said Rory, “would take all our capital. Let’s wait.”

Waiting, she nevertheless kept her eyes peeled. One day they lighted on a little jewel in Beverly, early American ranch style, for sale by the owner. After dinner that night she suggested a drive, steered her unsuspecting victim down the right street and managed a gasp. “Isn’t that a cute place? And for sale, too!”

“So it is.”

“Let’s look, Rory. What does it cost to look?”

A man answered their knock. “Oh, hello, Mr. Calhoun. I’m glad you could make it so early,” and drew from his caller a blank and bewildered stare; which he disregarded. “Your wife was here this afternoon. She said you might come tonight.”

Rory shot a glance at the innocent schemer beside him. A grin tugged at his lips. Suddenly he couldn’t bear to disappoint her.

In any case, it turned out to be a good deal. They moved in on their fourth anniversary.

Out in the patio stands a metal bucket, now filled with lemon leaves—the same bucket that once held a magnum of champagne on a far-off enchanted evening at the Mocambo.

Lita’s career, while not in the discard, is a sometime thing. If it doesn’t interfere with their common plans, she’ll take an occasional job, as she did in Red Sundown. But she prefers freedom to go where he goes—whether it be to Ojai, to their boat at Wilmington, or on location for Universal’s Raw Edge.

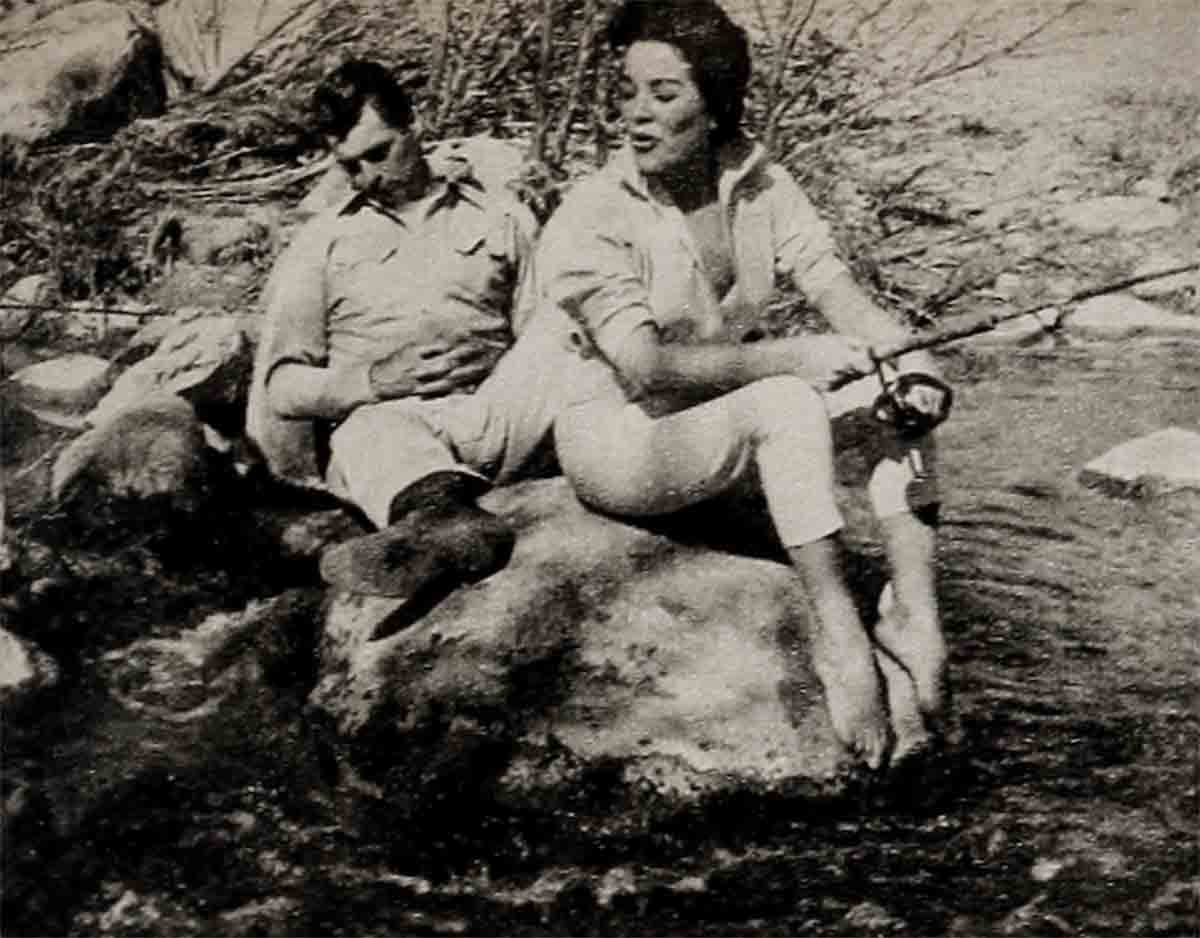

“If it’s a marriage, you want to be together. If it’s a marriage, you don’t change your husband’s habits, but learn to like what he likes. For me it’s been fun to learn. Once we went fishing with friends in the Colorado River. Everybody put money in the pool and the money would go to whoever caught the first fish, the biggest fish and the most fish. And who do you think won this pool? Lita Calhoun. I was in heaven. It’s entirely a new life and a better life. You don’t have to wear greasepaint all the time.”

Each has his theory of what makes a sound marriage, differently expressed but resolved to the same elements. “Some people,” says Rory, “fall hot in love, they marry, they hit the stars, time marches on, the glory fades, they didn’t marry an angel. Who’s an angel? They start wondering about all the others they passed up. They’re not satisfied with the one they loved in the first place. I am. Lita has plenty of temperament. So have I. Sure we argue. If you’ve got no fire, you’re not worth a tinker’s dam. But whatever’s bothering us, we lay it on the line.”

Says Lita softly: “You grow to love each other more as the years go on. The beginning and end is trust. If there is no trust, there is nothing.”

The years have drawn them closer in sorrow as well as joy. They’ve longed—and still long—for children. Twice their hopes soared and crashed when Lita miscarried. She thinks it hit Rory even harder than her. At first she was too sick to realize. When she did realize, he was standing beside her, his only thought to make her smile again. “Don’t worry, darling. Next time we’ll have twins.”

“Or quintuplets?” she quavered. cause you know I want twelve.”

Meantime they’re looking for a child to adopt. A boy of four or five, so Rory can take him fishing.

THE END

—BY RUTH HARRIS

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE JULY 1956