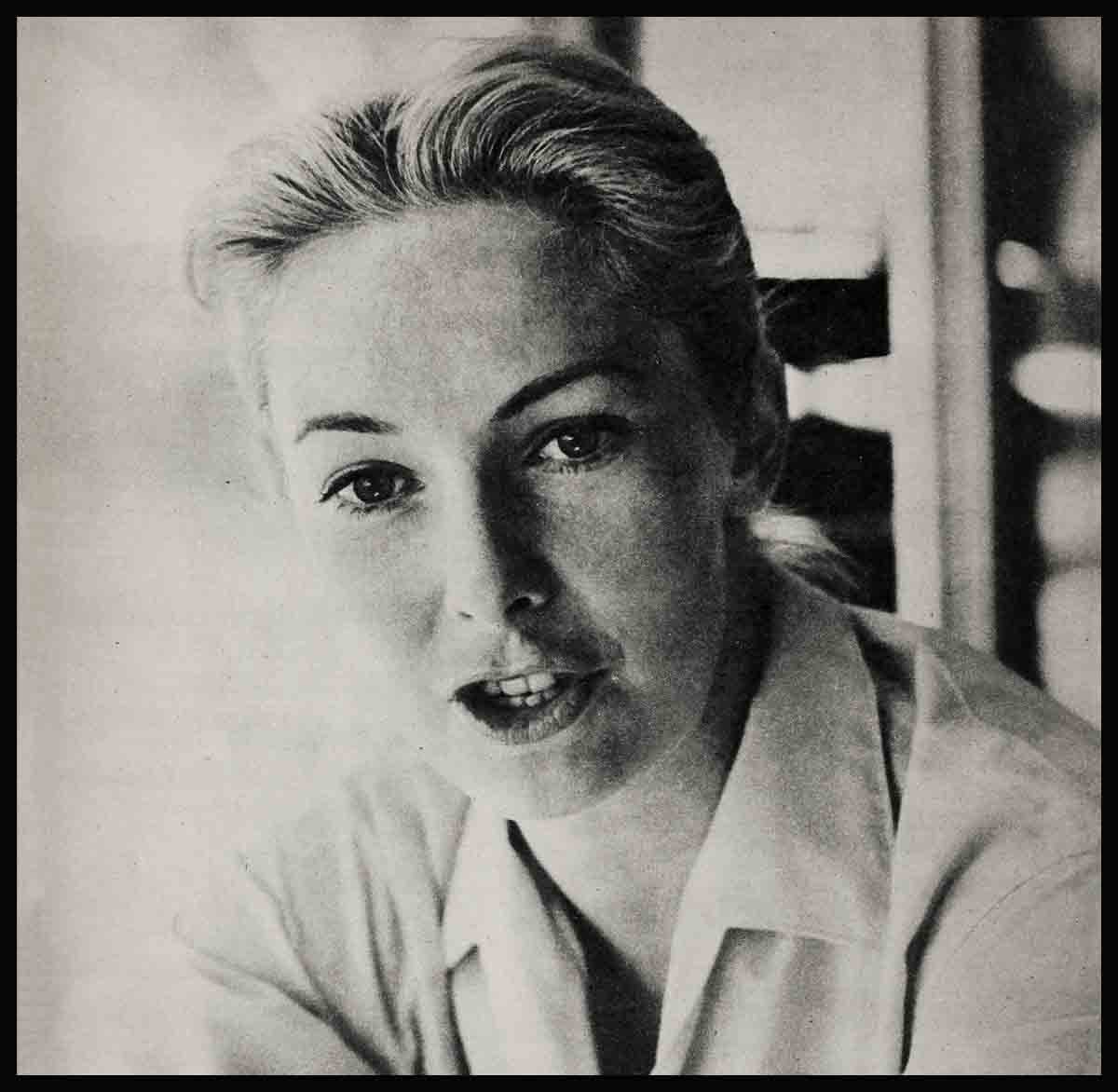

Sprite With Spunk—Jean Seberg

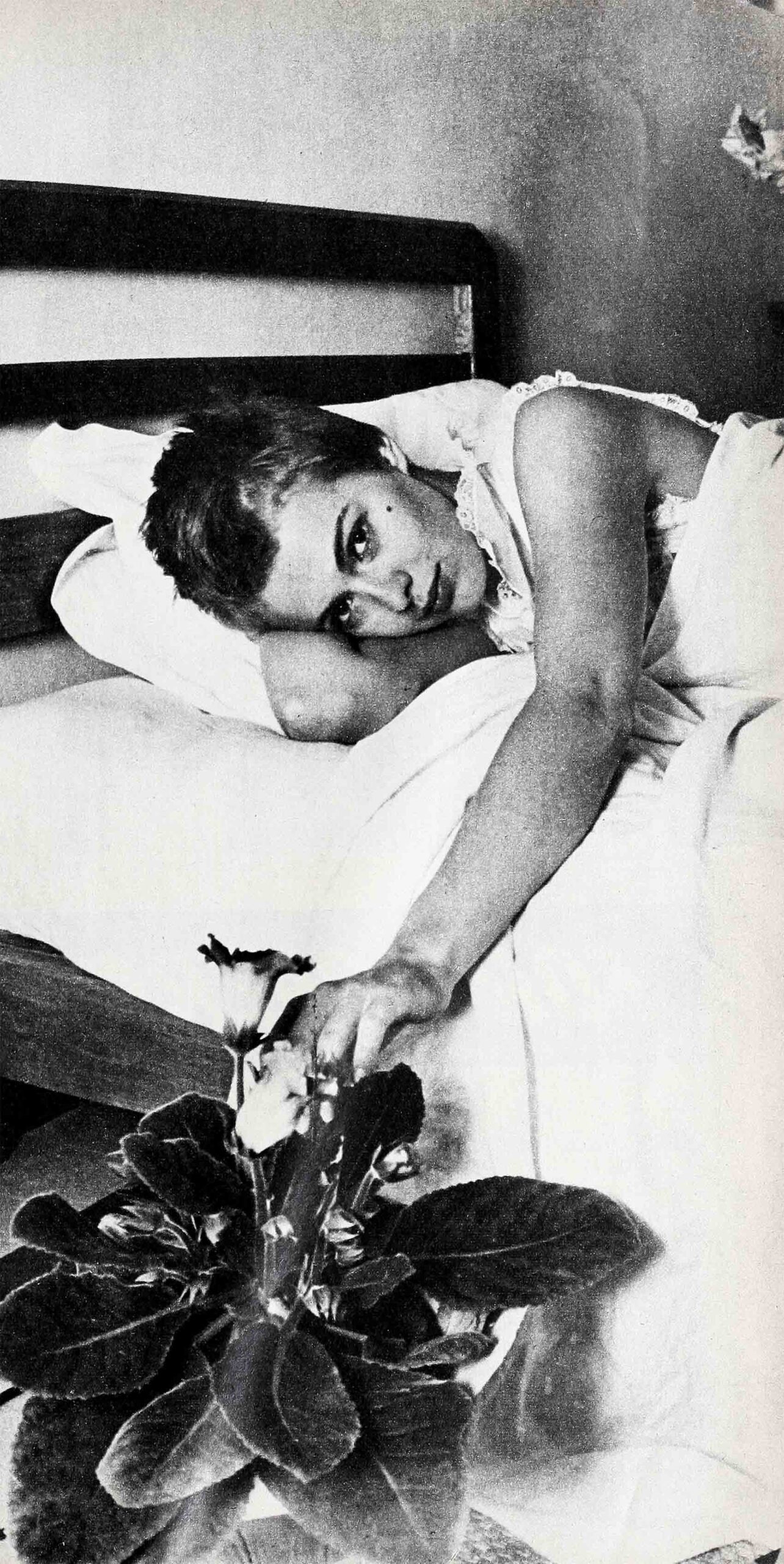

Jean Seberg reached for the glass of lemonade that was on the table. She sipped the drink thoughtfully and stared down the Riviera coastline that led to Nice. “You wear armored plating . . .” the columnist had said. She glanced across the table at the seat he had just vacated. “You wear armored plating, Jean, as a human being as well as an actress.”

She’d been in Nice only two months before, alone, without armor. Completely without armor the night she’d stood at the window of her small apartment, looking out at the lights, but not really seeing them. Finally, she’d turned back into the room. It was a tiny room, not the sort of place you’d expect to house a vacationing movie star.

Star? Her thoughts tripped on the word. Her name was on theatre marquees all over the world. But was she a star? More important, was she an actress?

She walked over to the table, where her mind had been all along. She carefully picked up a bulky envelope and reached inside for a pile of press clippings. Then she spread them on the table and began to read them again.

They’d come that morning, the “Saint Joan” reviews. The first ones she’d found, those carefully placed at the top of the pile, were the ones with the praise. The good notices. But the others were the ones she’d read, re-read, set aside, and kept coming back to. They were the ones she read through large, bitter tears. They were about “the girl in chain mail bobby sox,” the teenager who’d misinterpreted, mis-read, mis-emphasized” the wonderful lines of George Bernard Shaw; the new discovery who just didn’t measure up to her first part.

The girl in the apartment in Nice put her head in her arms and clenched her fists until they were like knots on the table. “Jean Seberg, you’ve got to get tough. You’ve got to learn to be tough!”

Mr. Preminger had tried to tell her what might happen, the evening she’d been packing to go home from London. The picture was finished. They’d all worked so hard, for so long, she was certain it couldn’t miss. Before the opening, she’d have three weeks with her family in Marshalltown, a month of personal appearances, then back to Paris for one of the biggest premieres ever staged. She was all but waltzing from the closet to the suitcase when Mr. Preminger stopped by her suite to talk to her. “Sit down for a moment, Jean. . . .”

She sat, but not terribly still, not very seriously. She hadn’t realized how hard it must have been for him to make the speech. As a producer-director, Otto Preminger was a recognized artist. He knew that you couldn’t always make pictures that would please everyone. He’d said before the start of the “Saint Joan”: “This is the biggest gamble of my film career.”

“Saint Joan” was more than an exceptional story, just as Joan, herself, was more than an exceptional heroine. In the theatrical world and the world at large, Joan was a legend, someone special and familiar. It was only reasonable to expect that everyone seeing the film would have his or her own personal ideas on the portrayal of Joan. Any production about the Saint would automatically be a sitting duck . . . and whoever played the role the first to be shot at.

Preminger knew that an experienced professional would understand if a barrage came. But he’d taken a teenager from Iowa with virtually no acting experience, given her the lead, coaxed her, bullied her, driven her through the filming . . . wondering all the while how much more she could stand while she was trying so hard to please.

Aside from her talent, he’d chosen her for her spirit and he was certain the combination would take her as far in the movie field as she wanted to go. He didn’t want the talent discouraged, the spirit broken by a few lines of small print. He had to make his speech long before the reviews were due, to give her time to accept the possibility of harsh, critical words, although they might never come. “Jean, you’ve got to realize that everyone may not like ‘Saint Joan’. . . may not like you.” He took a deep breath. “In fact, maybe no one is going to like you. You’ve got to be prepared. Do you understand?”

Yes, she understood, she said. Yet, when he left, he noticed the stars were still in her eyes. He only hoped they’d stay there.

They were washed away with tears not long after when the first reviews of “Joan” began coming in. “I’ve got to be tough,” she sobbed when she read them—so many times she’d lost count. And then, the tears would start again. “But right now,” she admits only to herself “I don’t feel very tough.”

So she donned her armor. As it turned out, she was still going to need it, on and off the set. When one scribe asked her about some of the more devastating reviews, she shrugged and said, “It’s too late to change anything now.” It was too late and she couldn’t imagine what else she could be expected to say. In print, however, it appeared that she had shrugged “a sophisticated shoulder” in a rather bored tired-of-it-all manner, to end the interview.

The sophisticated Jean Seberg? Well, she had to admit that she’d tried . . . the night of the Paris premiere. Mr. Preminger had given her a Givenchy gown for the event. “I was going up the stairs, very ritzy in all my finery,” she recalled later. “I was trying very hard to be sophisticated. But people kept crowding around, stepping on the train of the gown and I had to keep jerking it out from under feet. It isn’t exactly easy to smile and be dignified while you’re pleading, ‘Please get off my train.’ Sophistication-wise, I had the distinct feeling that I was falling flat on my face!”

Jean was beginning to learn what every star must learn. That verbal slings and arrows don’t necessarily stop with reviews. There were other reports, the ones that seemed to assume that her thoughts were a million miles from Marshalltown and that she couldn’t care less about going back, except for occasional red-carpet treatment.

That particular reporter should have been with her on her return from London. He could have listened as she frantically tried to recapture her mid-western twang, after three months of being coached for a British accent . . . read the one thought that was uppermost in her mind: “If I get home and say cawn’t or beeen just once . . . well, then I’ve had it!”

What a blow the scribe would have gotten if he’d been along to meet her brother David, aged seven. According to her mother, when the family had been getting ready to drive to Des Moines to meet her plane, brother David had sighed resignedly, “Guess we got to drive all that way to get the actress again!”

The actress was at home for three weeks. She swam at the YWCA, slept late, and went to the library. She put on her bobby sox again and went out for pizza with her friends, who’d come home from college. They still had common interests. They’d talk their heads off, and sometimes drive to Des Moines for jazz concerts. “Of course, there were changes,” says Jean today. “And I guess you’re well aware of the fact that everyone is watching you to find out if you’ve changed. I did feel that . . . especially since so many people were dropping in and mother was suddenly doing a lot of entertaining.”

But home is home. “And one thing certainly hasn’t changed,” grins Jean. “Mother was still giving me a hundred reasons why I should help with the dishes and clean up my room.”

“Being in movies hasn’t made you any neater,’ her mother sighed. “And Jean, some people are coming by. Would you please go upstairs and. . .”

“And put on something presentable,” finished her blue-jeaned clad daughter.

They both smiled, remembering the morning her mother had made the request several years before. At that time, Jean had trudged unhappily to her room. Her reappearance made her mother gasp. Daughter was nonchalantly floating down the stairs in her new purple formal.

When she reached the living room she graciously greeted the guests and then went about serving refreshments, quite straight-faced in her full length gown.

“I suppose I should have realized that you were eventually going to become an actress,” her mother told her later.

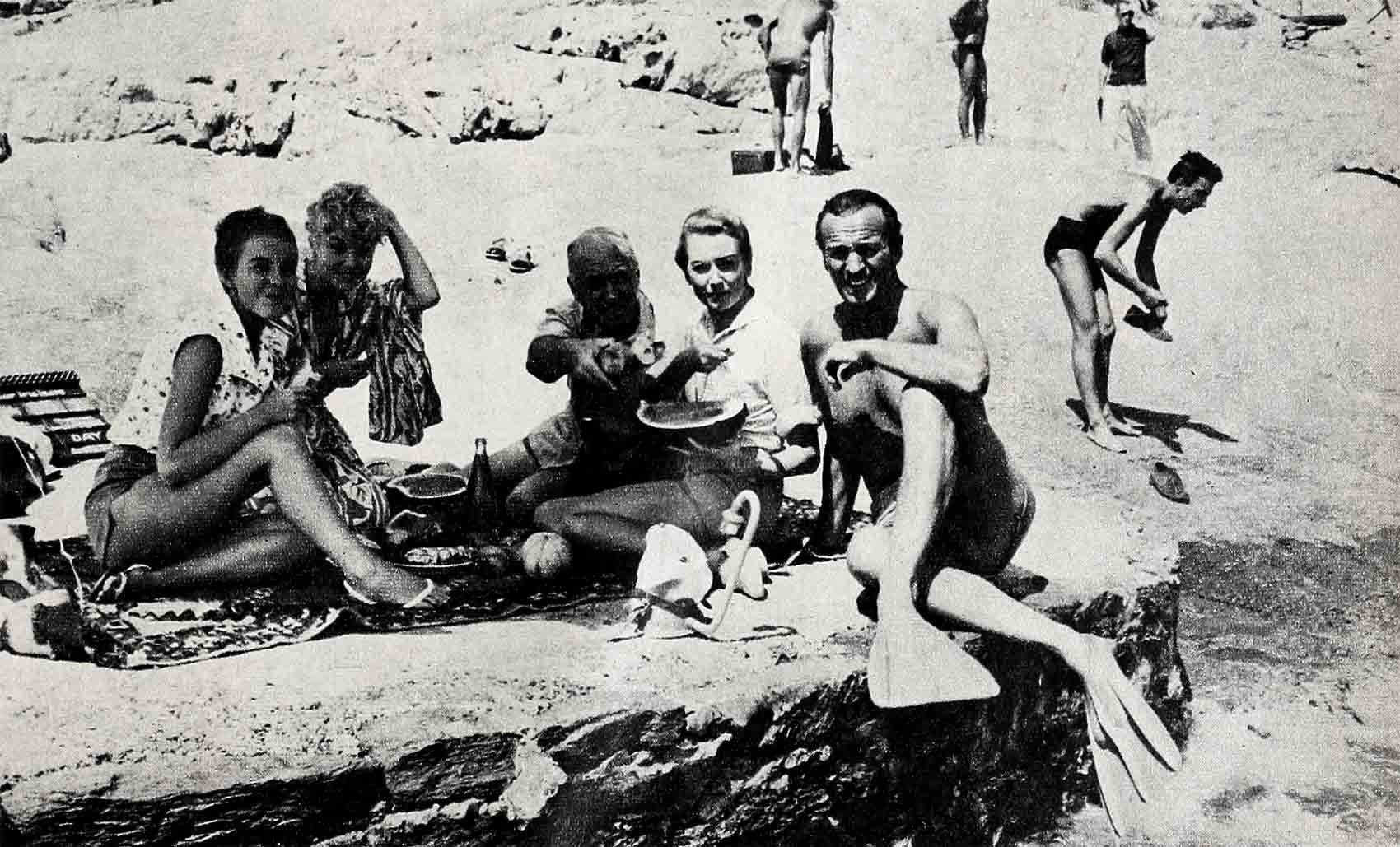

Home . . . and then Nice . . . after twenty-seven days of personal appearances. According to the papers, she’d run away to Nice, being as blase about it as if every eighteen-year-old vacations in Nice alone. She was the self-sufficient Miss Seberg.

Yes, indeed. Very self-sufficient. Especially the day she carefully locked the car with the keys inside and had to call a mechanic, a fellow who advised her that the only way to open the door would be to take it off the hinges.

She was going to be independent. Very independent. And she had every intention of living on the money she had in her purse. But then came the day she looked and found her wallet almost bare. It was, she concluded, a good thing her father was handling her finances. She had, she figured, about enough to wire him for more money.

She sent off a cable and went home to take stock of her cupboard. She found one huge candy bar and a package of tea bags. And she dined less than lavishly until the money arrived two days later.

But she got the rest she’d hoped for, and she had the chance to do a great deal of thinking . . . about the past, the present and the future. She took one memorable cue from a French traffic cop, the day he found her little car in a No Parking zone. He began to quote all kinds of traffic rules to her in French and, she recalls, “the ham in me came out. Two large tears rolled down my cheeks.”

The policeman asked for her identification and she gave it to him. “You have played Jeanne d’Arc?” he sputtered.

“Yes,” she replied in a small voice. He eyed her closely, then threw the license into her lap, hopped on his bicycle and pedalled away muttering, “Jeanne d’Arc never cried!”

Jean Seberg dried her eyes and murmured, “And Jean Seberg won’t do any more crying either!”

There was nothing she could do about the past, she realized. The results were in. “At first,” she remembers, “I felt so awful. Of course, everyone wants whatever they do to be an enormous success. But that’s something you can’t always have. Still, when there’s such a big letdown, you begin to doubt yourself. You seem to have done your best and it doesn’t seem to be good enough.

“You have to learn to be objective and analyze it. Perhaps emotionally I just wasn’t ready for the role. Perhaps I didn’t have the depth of emotion that comes just from growing up and living.

“Mr. Preminger was wonderful about it. It would have been very easy for him to have taken the role in ‘Bonjour Tristesse’ away from me. But he insisted that he still had confidence in me.

“The role of Cecile is much easier. She’s a girl whose personality is closer to mine. Every girl should aspire to be just like Joan of Arc, but how many can be?

“The reviews, the bad ones, I put them away . . . but I still make myself read them. I suppose I’ve always tried to face things. Back in Marshalltown, I used to be terribily shy. So I used to bluster and bluff my way through things—all sorts of activities.

“In a way, I suppose it sounds corny, and very idealistic, but now I feel that I’m much better off for having gotten those reviews. Otherwise, I might have felt that there was no need to work as hard again, that I could coast. But this way, I’ve become increasingly aware of what I have to do.”

No one is selling Jean short. “She has the talent and the stamina for stardom,” says a publicity agent who toured with her for personal appearances around the States. “And how that girl can work. She’s fantastic.

“In Montreal, seventy-five percent of the people speak French. So we got to Montreal and Jean went on the radio and talked for fifteen minutes in the language. After only a few French lessons.

“At one midnight show in Philadelphia, she adlibbed for forty minutes with the m.c. There was never a minute’s hesitation; she was never thrown by questions, never at a loss for words.

“Her poise was remarkable, even when things weren’t going so well. At the party for her in Los Angeles, some of the columnists were trying to antagonize her. ‘How do you feel about starting your career by playing a part like Saint Joan?’ one of them asked.

“Jean answered, ‘It’s very challenging.’

“After which, the columnist snapped, ‘That’s a cliché. I want an honest answer.’

“Jean bit her lip, but she didn’t lose her temper. She just said, ‘I’m trying to give you an honest answer.’ ”

“She’s changed since ‘Joan’,” says a friend who worked with her in both London and in France. “She’s the same girl, but she’s different, if you know what I mean. ‘Bonjour Tristesse’ is her second film and she is taking a different attitude. To a great extent, she’s learned the ropes of the business. She’s no stranger.”

Still there was a certain tenseness. And a tiredness. “But such a wonderful tiredness,” she says. “I’m finding out what kind of routine I have to follow when I work. I usually have dinner alone in my room at night, read and then go to sleep. Once a week, I go out for dinner.

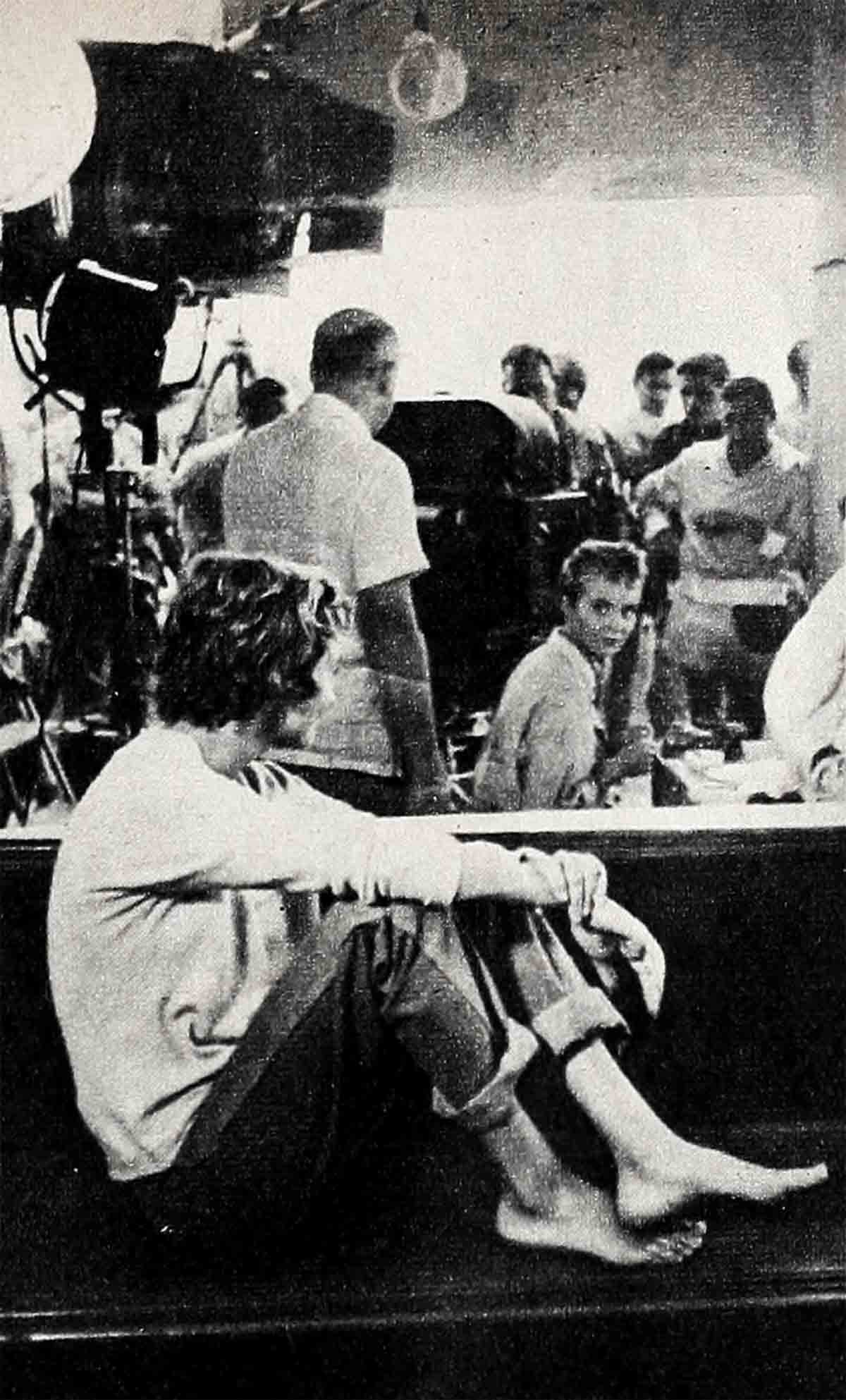

“On Sundays we drive for three hours to see rushes. I don’t like to watch. It’s terrible to have to look at yourself blown up on the screen. And if you do see something you don’t like, there’s nothing you can do. I think there’s a risk of becoming very studied and mannered.

“But on the other hand, if you’re doing something wrong, like bobbing your head or adopting any other sorts of mannerisms, you can catch them and correct them. And,” she adds, “Mr. Preminger thinks it’s good for me to see rushes.”

She grins, “And what he says, goes. He doesn’t make exorbitant demands. He’s begun to let me have more of a separate life now that I’m getting the hang of the movie business. He doesn’t call my personal life part of work.”

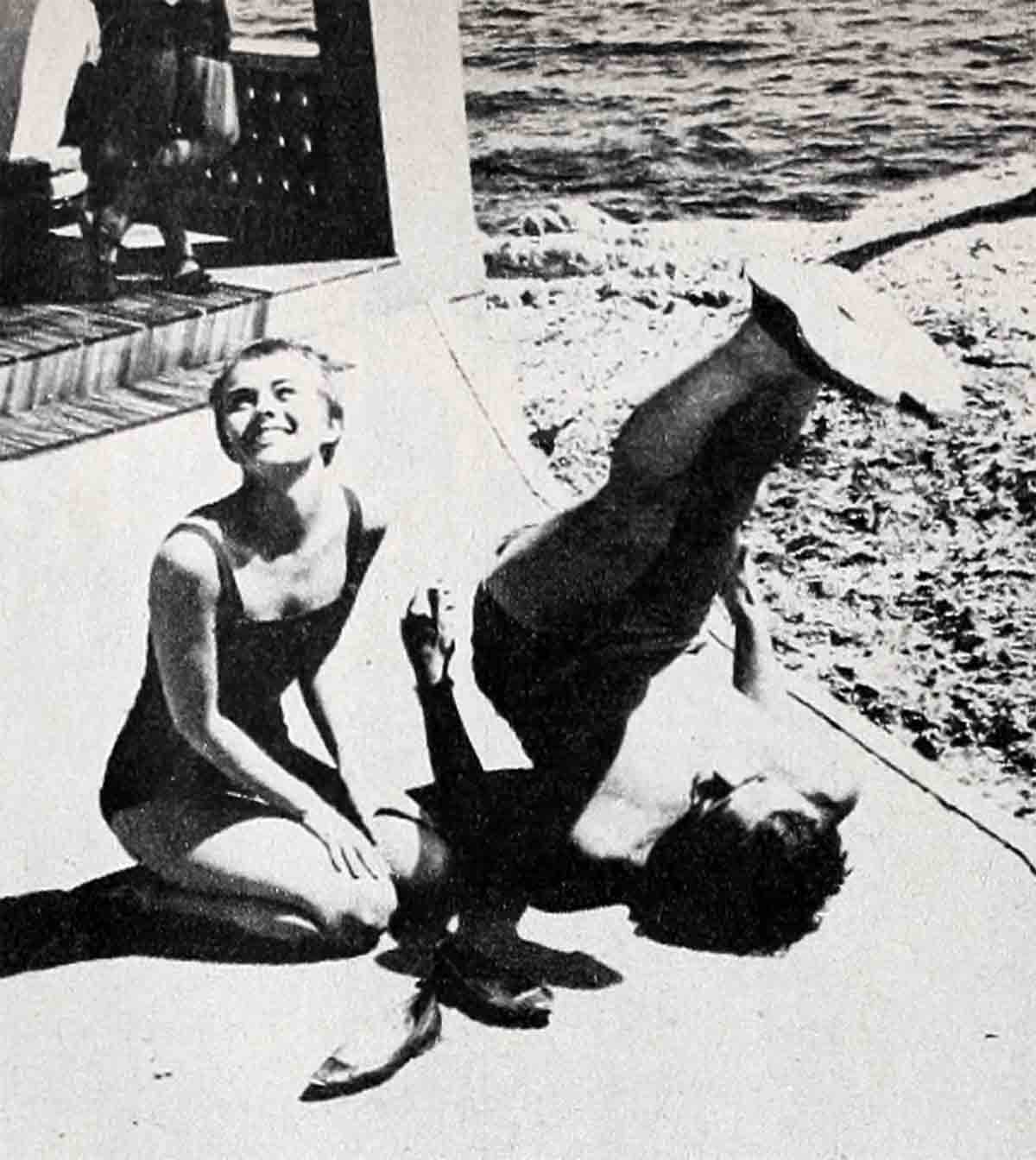

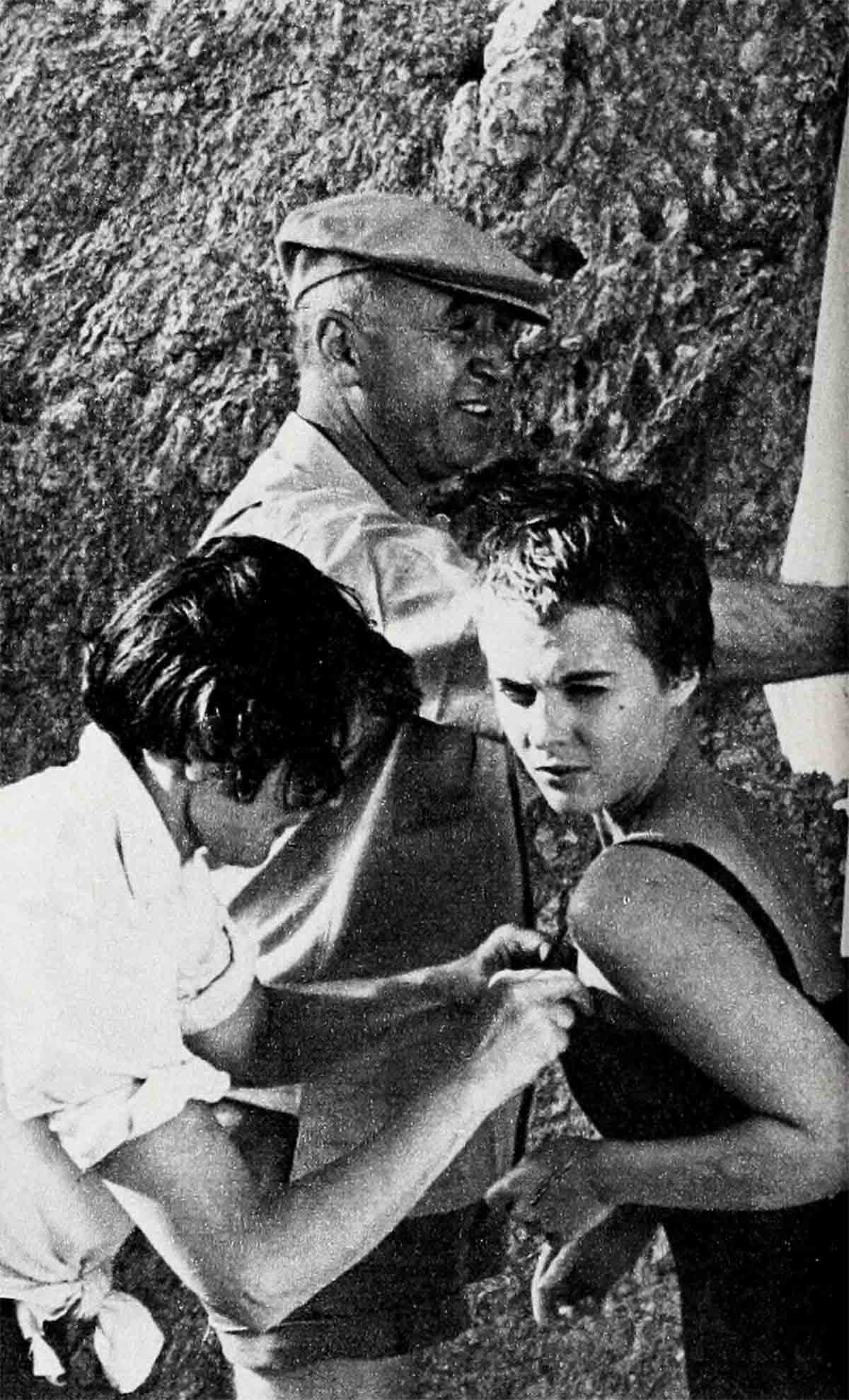

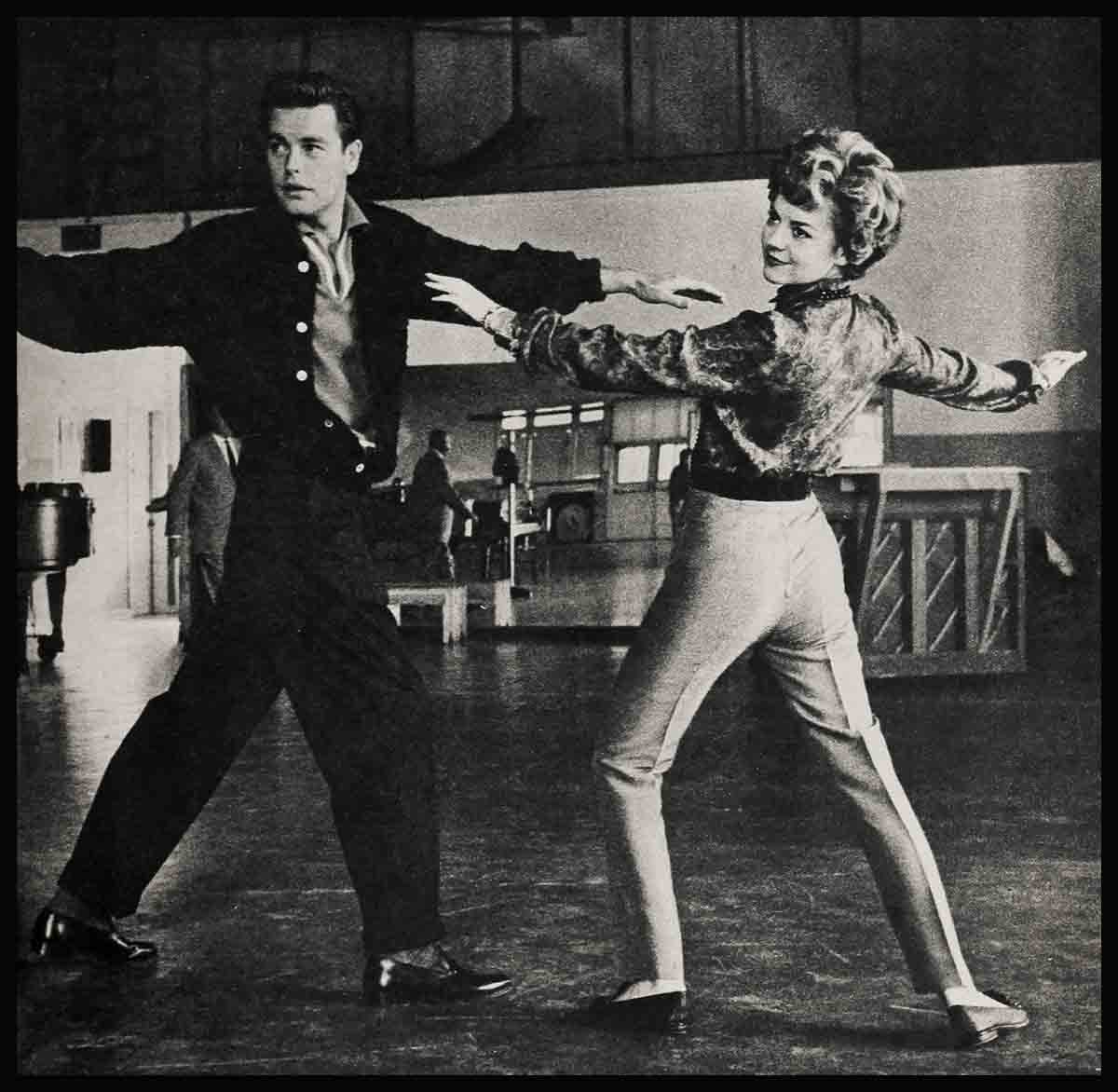

She goes on, “I have a lot to learn about acting, but the only way I can learn is to act. This time, I’m not in the hot, hot spotlight, and David Niven and Deborah Kerr have been wonderful.

“They’re so relaxed and easy. Nothing seems to upset them. They can talk to people between scenes and still not break the spell. That’s something else I’m having to learn.”

Invariably before the cameras would turn, David would make the atmosphere light with joke. Once, when he saw a frown on her face, he patted her on the shoulder and remarked, “Remember, it’s only a movie and people are going to pay seventy-five cents for a ticket and say, ‘Who was the guy with the mustache?’ ”

As “Bonjour Tristesse” was ending, Jean was preparing to return to the United States. “First I’ll visit my family. Then I’m going to New York. If there’s no other picture right away, I’ll take ballet lessons and some drama lessons and I’d like to visit movie sets. I’ve no idea of how other actors work. And I still haven’t set foot in Hollywood! My set is about the only one I’ve been on,” she laughed.

But she was a girl certain of her future. It’s as David Niven said on the set one day, “I feel so sorry for anyone who isn’t an actor. Oh, sometimes I get discouraged and gripe . . . but then I ask myself just what I’m griping about.” He shook his head and repeated, “I do feel sorry for anyone who isn’t an actor.”

Jean smiled. She knew what he meant. And she said softly, “And so do I.”

THE END

—BY BEVERLY OTT

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE DECEMBER 1957

gralion torile

11 Ağustos 2023Very interesting subject, appreciate it for posting.