Why Robert Wagner Dates A Girl Only Once

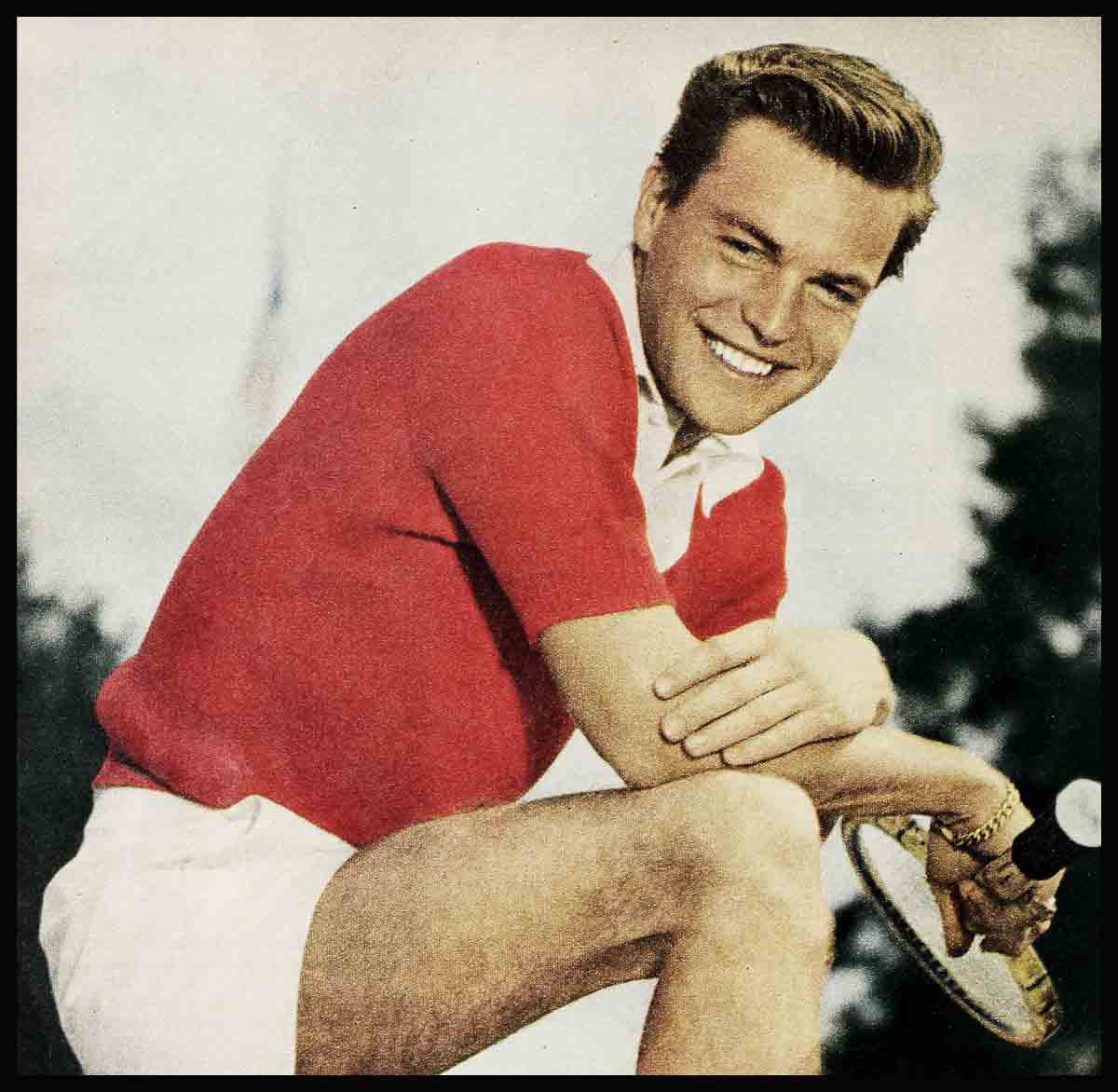

Bob Wagner woke up in a Wichita, Kansas, hotel one morning last February, officially a year older than when he had turned out the lights the night before—twenty-five to be exact.

Sleepily, he yanked a fan of yellow Western Union greetings from under his door—happy returns of the day from his mother and dad in La Jolla, California, his married sister in Claremont, pals at 20th Century-Fox and interested parties, male and female, around Hollywood.

He read them all before he scraped his face, pulled on his clothes and ordered his breakfast. Then, bucked up and happy, he breezed into an auditorium packed with 3000 high school students. That was the reason he was in Wichita—to make new friends for himself, and to publicize his latest picture, White Feather.

The gang greeted him singing “Happy Birthday.” For an hour he had a ball holding open forum on movie-making and Hollywood life in general. He answered questions about everything—screen stunts, camera tricks and techniques, the joys and headaches of a screen star’s life. When they yelled, “Hey, Bob—when you kiss Marilyn Monroe on a set how do you really feel?” he came back, “When you kiss a girl how do you really feel?”—and the meeting turned into a good-natured riot as ordinarily happens when Bob hits a town.

He was just making his exit when a deeper voice hailed him, this time in a cynical tone. “Say, Wagner,” needled a reporter, “you’re a big boy now. What’s the matter with you? Why don’t you fall in love? When are you going to get married?”

Bob Wagner felt his face get hot, and suddenly the starch drained out of his act. “I’ll have to pass on that one,” he said. “So long, everybody. Got to make a plane.” But his voice was flat. For him the party was over.

The bellhop was slinging his bags into a cab at the hotel when the clerk beckoned him. Hollywood calling. And the gossip columnist’s insistent voice was too familiar. “About this Anne Stebbins, Bob,” he pressed. “What cooks? Is it. a romance? Are you engaged? Give me a quote.”

“Okay,” replied Bob wearily. “I will. She’s a nice, attractive young lady—but we’ve never had a date. You’re on a crazy, cold trail. I’m just a friend of her father.”

“How about that picture of you two?”

Bob had been at the Friars’ testimonial to George Burns and Gracie Allen down at the Biltmore. Alone. He ran into Artie Stebbins, his wife and their eighteen-year-old daughter. A news photographer shot He hadn’t seen her since.

“Ha!” scoffed the skeptic. “Still kidding the public, hey?”

Bob hung up, thinking you can’t win, The others they’d romanced him with raced through his mind —Barbara Stanwyck, Debra Paget, Terry Moore, Joan Collins—women and girls he’d never even taken out on a date. Suddenly he felt a hundred and two and as jumpy as a jack rabbit. In the rest of the twenty-three cities he visited he didn’t dare show up with a girl in public, including New York, although a very beautiful one he knew lived there and he liked her a lot. But on his last visit he had escorted her to a premiére. One date and the columnists had him engaged to Josephine Abercrombie.

Bob Wagner has been back in Hollywood since early spring, but in his own home town he’s still a bachelor on the run. If he gets within two feet of a girl people say he’s in love. If he is seen out on a date its a Big Thing. He’s had his telephone number changed twice since he got home and he’s thinking of yanking it out.

Now, most eligible young Hollywood males learn to live with this hunted feeling, as others besides Bob—like Rock Hudson, Tab Hunter or George Nader—could easily confirm. Bob has been in pictures since he was eighteen, a swoon star for almost three years now, and except for a supposed romance with Debbie Reynolds, very hard to stick with a Valentine all that time. In fact, you practically have to dig out Wagner’s dates with a Geiger counter, a fact that reporters find increasingly annoying as Bob’s years and his fame grow.

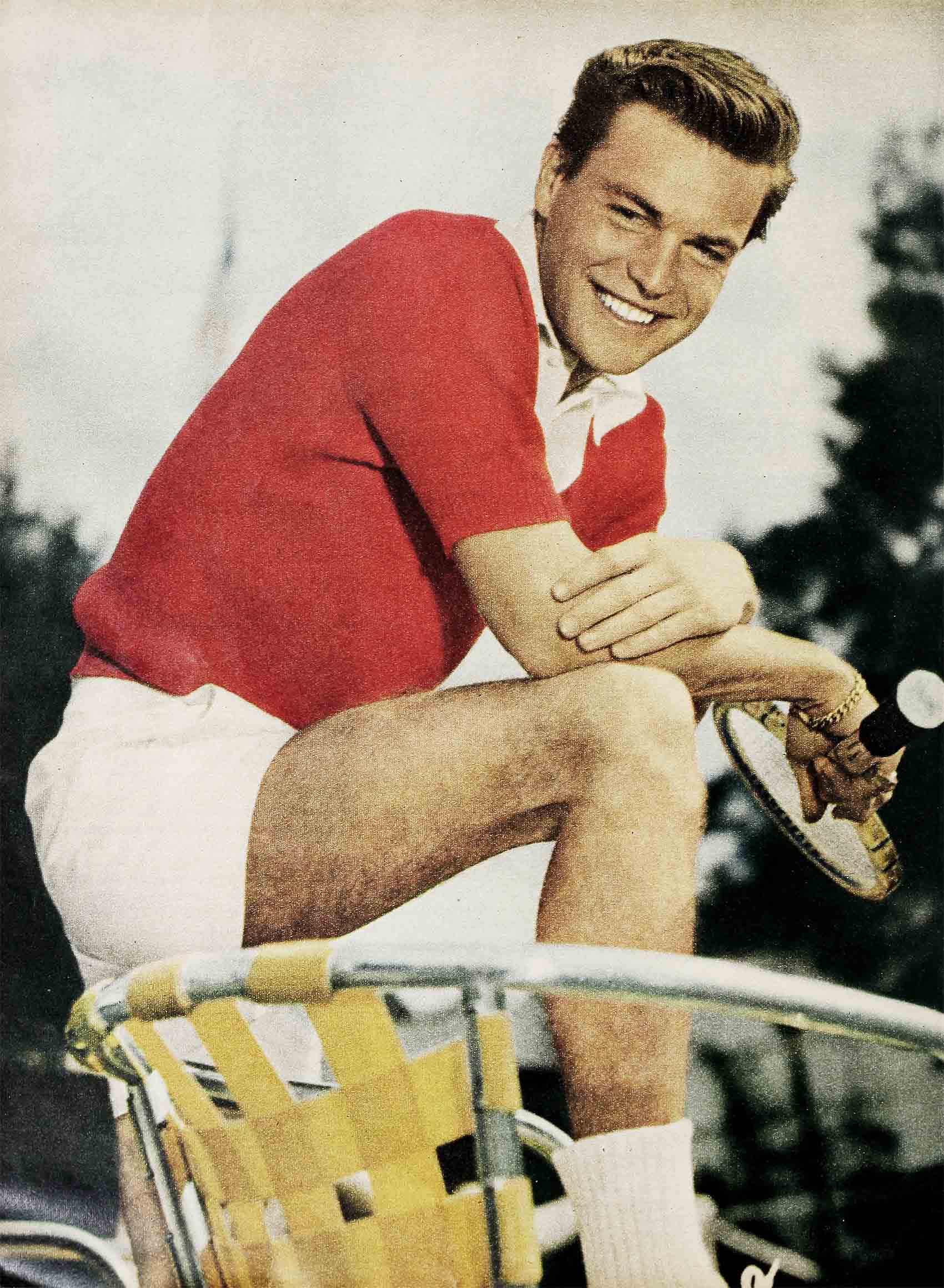

Of late Mister Robert John Wagner has been popping in and out of his apartment in Beverly Hills like a restless gopher. He came back from three months in Mexico to take off on this nation-wide personal appearance junket. Home again, he had barely riffled through his mail before he roared off in his Thunderbird to La Jolla to visit his folks. Before a phone call could reach him there, he had hopped on the invitation of Leo Durocher over to Phoenix, Arizona, to pepper it up with the New York Giants in spring training. Finally cornered at home, he was packing his bags to run up to San Francisco next day. Bob looked frayed and he confessed he was twelve pounds under his fighting weight. Asked why he didn’t sit still for a while and cool off, he grinned.

“This town’s too small,” he observed nervously, gazing out the window at a sprawling community which approximates 4,000,000 souls. “It’s the greatest when I’m on a picture, but right now I’m not.” When Lord Vanity ran into leading lady trouble and was canceled until summer, Bob doped out this good will tour himself.

“When I’m not busy I blow,” he explained. “If I hang around here on the loose I just get involved.”

What’s wrong about that?

“You mean with girls? You, too?” sighed Bob. But he can be reasonable.

“For some guys, nothing I suppose,” he began reluctantly. “But for me everything. The main reasons are: I’m not in love. I’m not interested in getting that way. I don’t want to marry yet. And I don’t want to waste all of my time, my thoughts and my energies on something that doesn’t yet make sense—I’ve got other places for those. On top of that, I find it sort of silly, embarrassing and undignified to have this heartbeat fiction floating around when it’s so crazy. Now, if I did tumble I’d want everyone to know it. But I haven’t yet, so why work up a storm over nothing?

“I date girls all the time,” allowed Bob. “But usually I duck in and I duck out because that’s the way it has to be for me. Usually one date and goodbye. No entangling alliances. And when I do that I don’t let anyone know about it or catch me if I can help it, because then it’s the old story: I’m hooked, I’m going to get married, it says here, I’m this and that—and who cares? I don’t believe my love life means a nickel to my career. I don’t think anything does except what Robert Wagner does up there on that screen.

“That may sound selfish,” Bob conceded, “but actually it’s not. Nobody’s in love with me either, and when a phony item gets out—well, I don’t like to hurt anybody. Now I know reporters run out of something to write. So they take anything that looks promising and build up a story. I don’t blame them. If they catch me with a girl, well they’ve got me and it’s okay— an occupational hazard, I suppose. But frankly, I dodge.”

A case in point, Bob said, was Anne Stebbins. When Bob was in Phoenix working out with the Giants it wasn’t mysterious that Anne was there, too. Her dad, insurance man Artie Stebbins, is an old friend of Leo the Lip’s. In fact, he introduced Bob to Durocher. But even with that tie-in Bob figured it was risky to be nice. When he was asked to a party at Leo’s it was natural for Anne to expect him to take her. Instead Bob had to dodge. “What do I want to waltz you around that gang for?” he kidded her out of it. “I want to spend my time with Willie Mays.” He felt like a dog, but he also knew what would happen if they showed up together again.

“I made a silly statement once when I first hit pictures,” grimaced Bob. “Said I’d get married before I was thirty. Now each birthday the heat’s on. What a crazy crack!

“How could I possibly know then when I’d get married? You don’t just wake up some morning and say, ‘Nice day—think I’ll get married.’

“I’ll give you a scoop,” razzed Bob. “I like girls. Couldn’t get along without ’em. I’ve dated since I was in knee pants. I’ve gone steady and I’ve thought I was in love. I’ve been unofficially engaged a time or two. I’ve tossed over some girls and been tossed hard myself. But I’ve never regretted it. Maybe if I had stuck with the steel business I’d have been married by now. But something else happened to me. And that something else makes a big difference. You don’t just walk out and say, ‘I’ll have a career,’ either. You work for it. I work almost every day, shooting or not. It’s a full time job. So is marriage. Something’s got to give.”

A stack of mail three feet high stood by his desk. “Came in while I was gone,” he revealed. “I get up at six o’clock in the morning and wade through it. Two thousand letters pile into this apartment every week, not counting the rest. It costs me $150 a month to take care of that. But a lot of it has to be taken care of by nobody but myself. I’m lucky to get it, of course.

Bob kept the phone hot. “I’m on this thing all day long sometimes,” he explained. “Contacts. In this business you have to keep them warm. It’s ‘Root, hog, or die!’ You’ve got to keep rustling jobs for yourself even when you have a studio contract. People say I’m too serious about my job. Maybe I am. But I’m not kidding myself. I’m not really a big star. I want to be so good they can’t ever fire me. Then I want to make my own pictures. I tried to buy a couple of stories but I couldn’t clear all the rights. That reminds me—” he dialed another number.

“I’m a quiet romance item strictly because I want to be,” stated Bob later. “Truth is, I’m just in no hurry. My dad married my mother when he was thirty-seven and he went with her two years before that. They’ve made a great team. One of my best friends married first at forty-five—same result. In fact, when I look around I’m not sure early marriage is such a good idea in Hollywood. But of course,” admitted Bob, “there are others who make you think it’s the greatest idea on earth—like Rory Calhoun and Lita. I don’t know about that side of the picture—it must be terrific. All I know is my side.” He waved his hand around. “People say, ‘But don’t you want a home of your own?’ Man, I’ve already got one!”

Bob has lived for a year in a house in Beverly Hills, five minutes from his studio and less from the best restaurants, movies and shops. Inside there’s a big fireplace, sturdy furniture, soft rugs and soft music. Remington prints deck the walls, guns slant against corners and books line the shelves. Upstairs two bedrooms will put up his folks for the night. A phone exchange handles his calls, a valet and a cleaning woman keep things tidy.

“But the best thing of all,” said Bob, “is that when I flip the key I’m off and free as the birds. No waiting around and nobody to run a check if I don’t hurry back. Right now that’s how I like it.”

Bob’s off quite a bit these days. Up to Del Monte for golf, down to Palm Springs for some sun, away to La Jolla for home life. If you press him he’ll admit he’s got girl friends in each of those places and a few more besides. “Just girls you wouldn’t know,” he claims, “and I hope you don’t find out about! But none of them threatens to change the picture.

“The truth is,” he analyzed himself. “I’m not too sure I’m psychologically ready for marriage, even if the right girl walked into my life tomorrow. As of now, I’m not certain I’d make the ideal husband at all. I’m pretty independent and always have been. I’ve got a temper, too, and when I blow I can go real good. I haven’t any sense of time—oh, I’m reliable for a set call or a business appointment, all right. But when I’m off the hook I don’t wear out my cuffs digging a wrist watch. I’m extravagant. Maybe I’m selfish, too, although I don’t think so. At least this doesn’t look like it.” He flipped over a jeweler’s bill. $3500. “Don’t get excited,” he teased. “Mostly for my mother.”

Bob drags down $75,000 a year now, but he’s in a seventy-eight per cent income tax bracket, and he keeps around $12,000. He could tally more if he wanted to on sidelines. But he’s not interested. “Pictures are all I’m trained for and that’s it for me,” he said. “I don’t really give a damn about money. I like to spend it, sure, but piling it up worries my business manager more than it does me. I’d rather have a good part than the pay check for it. Right now I’ve got one in mind Id do for nothing—if they’d let me. What would a wife say to that? Probably crown me with an egg beater!

“Besides, there are lots of things I want to do before I settle for a picket fence. I want to travel all over Europe and South America, study the museums, see the country, meet the people. How can I ever get really good on the screen unless I keep putting things in here?” He tapped his handsome noodle. “I didn’t go to college. Until I made pictures I hadn’t gotten around much. You know what I’m doing most nights when people think I’m out holding hands with some doll? I’m camped here on this couch, reading. Sometimes all night. They aren’t romance. yarns,” he added.

“Romance just has to wait, that’s all,” stated Bob. “You get on a spin with a girl in my spot and you spend all your time answering questions. Get seen twice with the same one and you’re on a hayride. True or false, your public believes it, even your best friends, and after you read it day in and day out, sometimes you do yourself, which is worse. It’s insidious. So when the time comes—as it always does unless it’s real—and you have to do something about it, well, you just take off with a bump because it’s the only way. I know,” declared Bob. “I’ve had experience.”

It wasn’t necessary to ask him with whom, because that was easy to figure—Debbie Reynolds. Publicity built that friendship up for Bob to a Big Thing—and publicity broke it up, too.

Bob Wagner isn’t cynical, though. Nor is he a misogynist or a hermit. You can’t blame him sometimes for his skittishness about affaires de coeur. But that can be a prescription for loneliness, too.

“Well,” he conceded, “of course you can’t have everything. I’m not saying this lone wolf routine is one step from Heaven. There are good things and bad. But I can’t honestly say I’m ever lonely. It’s no fun eating alone but that doesn’t happen often. At breakfast I know all the waitresses at Armstrong Schroeders, at lunch I’ve usually got an appointment and if I haven’t a date I’ve usually got an invitation for dinner. You know how it is with young, unattached guys in Hollywood. You don’t pick up the phone—it picks up you!

“Seriously, though,” said Bob, “I’m very lucky. I’ve got some wonderful friends in this business—oh, a slew of them. They’re not all exactly in my age bracket but somehow they let me hang around—and if I have a girl she’s welcome, too. They don’t have photographers around those places.

“Of course,” he said, “maybe some day I’ll wear out my welcome, I’m not kidding myself that I’ll float along solo all my young life having a ball. I know things will change—me, too. I want to get married some day, for sure. I want children. I’m a nut about kids. Always have been. On this tour I can’t tell you how many thousands of kids I visited and my heart flipped a hundred times because most of them were in polio and muscular dystrophy wards. You can’t beat a family. Maybe though,” grinned Bob, “when I tie up with one girl nobody’ll believe it. Or they’ll pull a switch—and try to break it up!”

Asked what kind that lucky girl might be, Bob confessed, “That I wouldn’t know. I’m not too sure she’ll be an actress. It might be rough having a professional rival for your wife. But on the other hand, when you’re in this business you’re really in a world apart. People who aren’t actors can’t understand a lot of things you have to do, ways you have to act. Why, even my own folks give me blank stares sometimes when I try to explain and they’ve lived around Hollywood quite a time. So, I don’t know, I really don’t. My type? Well, I guess I’m not being particularly original, but I like Grace Kelly’s type—smart, independent, beautiful—and a lady. Maybe it’s a corny word but she’s got class. I’m a great admirer of Jean Peters, too. There’s an honest, sincere girl for you. I like Mona Freeman; she’s really an old friend. Just say I like girls. And I only hope when the chips are down, the one I love loves me.

“When that happens I’ll get, married so fast it’ll make your head swim,” Bob promised. “And I hope for as long as the vow says. Tell you what, Dad, I’ll call you first and tell you when I’m ready to take the gas. But meanwhile, come on over to Romanoff’s. I’ve talked so much my throat’s cracked. I need a drink. Got to kill those amoeba bugs I picked up in Mexico.”

So he flipped the key. At Romanoff’s, Bob ordered a Martini and sipped it reflectively. “You know,” he said, “it may sound silly and even superstitious. But I guess the really big reason I don’t want to get mixed up with anyone in the heart department just yet is because I don’t want tines to change. I’m the luckiest guy in the world and I’m scared to rock the boat.”

The Mexican bartender took Bob’s empty glass. “Mas?” he asked in Spanish.

“No mas, gracias,” refused Bob. “I don’t need it,” he explained. “I’m feeling on top of the world right now. Anyway, I’ve got to blow. Where you going?”

Home to the wife and kiddies, and how about him?

“I turned the key, didn’t I?” grinned Bob. “That means I’m off—and don’t you wish you knew where!”

THE END

—BY JACK WADE

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE JUNE 1955