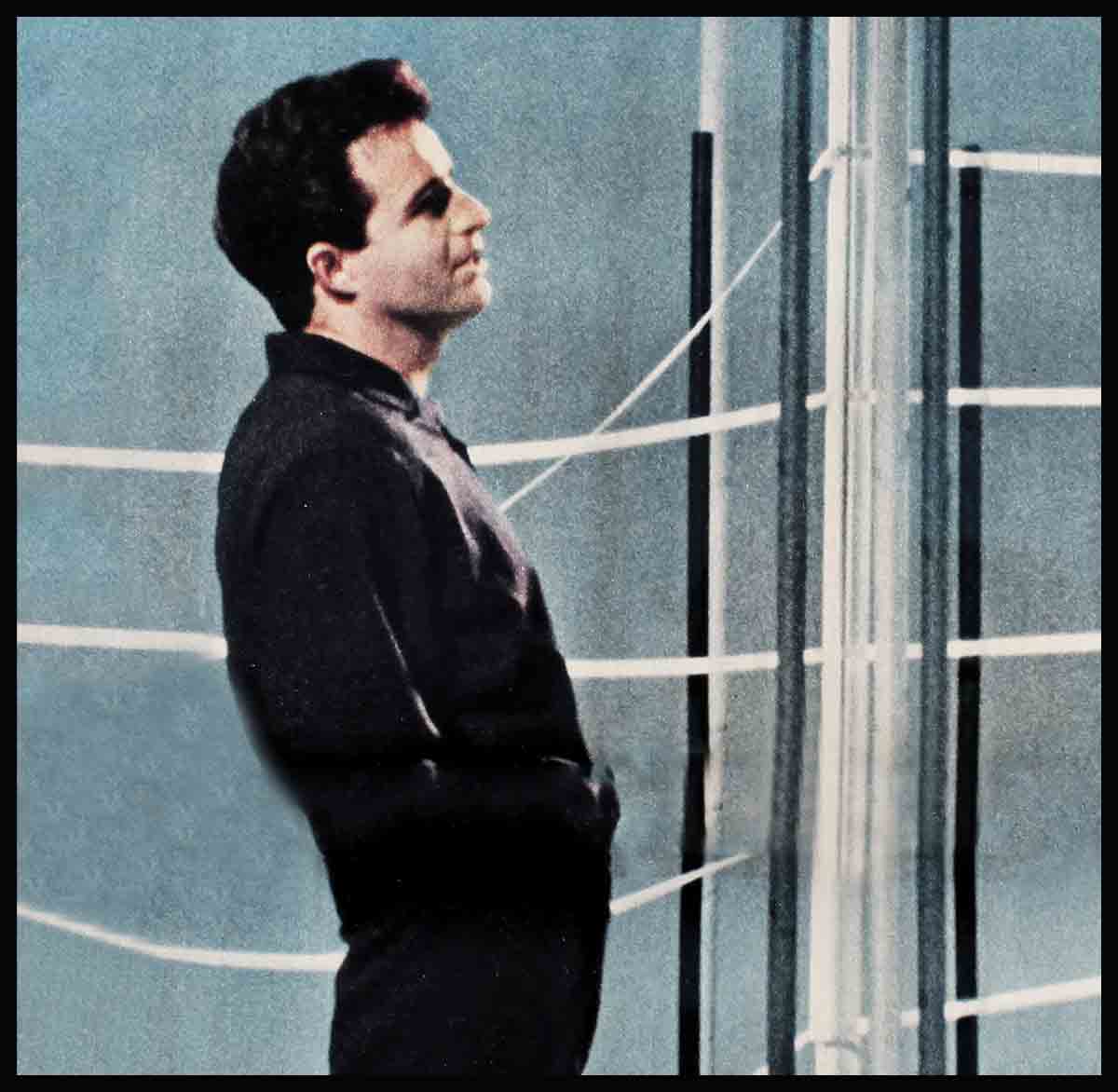

Vince Edwards His Life Story

BOOK-LENGTH BONUS One night about five years ago, Vince Edwards was singing in a Hollywood night spot called Plymouth House, when a burly type stalked up to the mike, snarled, “You sing sarcastic”—and punched Vince square in the mouth. In a flash the man, a big-time West Coast racketeer, was flat on the floor with a broken nose. For days afterwards, two hoods were out looking for Vince Edwards. Luckily, they never caught him. Some months later, while knocking around the Orient, Vince strolled into a night club on the outskirts of Manila. “Who owns this place?” he inquired.

“I do,” rasped a voice. Vince turned to see his old Hollywood assailant rushing toward him.

“I thought he was going to kill me,” recalls Vince today, still puzzled. “Instead, he threw his arms around me and greeted me like a long lost pal. I sang at his club and was a guest in his home for two months.”

The anecdote illustrates a perverse but potent fact about the black-browed, brooding, six-foot-two, 213-pound bundle of contradictions called Vincent Edwards: At first exposure, he often irritates, sometimes infuriates people. But in the end he has them hooked.

Some thought like this flashed through Vince Edwards’ mind last spring at Hollywood’s annual Academy Awards. Striding unannounced into Santa Monica’s Civic Auditorium, Vince drew the loudest cheers of any Hollywood star. Standing by his side that night was Shelley Winters, the only friend Vince had when he first hit Hollywood. “It gave me quite a turn,” Vince later admitted. “Up there handing out Oscars with Shelley—after twelve long years of obscurity. Ironic, don’t you think?”

Nothing but “dogmeat”!

What Vince Edwards meant was that not one of the Hollywood elite who honored him would have looked up—much less given him a break—before “Ben Casey.” In those twelve barren years they relegated him to dogmeat acting jobs—mostly hoods, thugs and gangsters—occasionally dangling a prize bone before his nose, only to snatch it away when he snapped hungrily.

In that time, to keep his stubborn hopes and big body alive, Vince was often reduced to living like a beach bum, operating out of Schwab’s drug store, bunking with any buddy who would take him in—and even fast-talking meals from random girl friends.

To keep going he peddled real estate, labored on an oil exploration gang, sang for peanuts in small cafes and was cage boy for a lion tamer’s act. He was once down to a lone two-bits which he spent for a sickening dinner of fudge.

“Until two years ago,” sums up Vince, “I was deep in despair with no idea where my life was heading. I’m lucky,” he adds with massive understatement. “Usually Hollywood uses up guys like me and throws them away.” About that time, in fact, one friend thought he was doing Vince’ a favor by telling him, “Look, Vince, you’re over thirty. You’ll never make it now. Why don’t you quit and try something else?”

“Ben Casey,” of course, changed all this. For almost a year Vince has amazingly scowled his way to record Nielsen ratings and Emmy nominations. He’s made 10 to 11 P.M. Mondays a prime sweet-agony hour for 35,000,000 Edwards addicts. Mostly they’re women reluctantly fascinated, like the one who wrote him: “I hated you at first,” she confessed. “But after a few minutes—golly!”

Now, postmen get lumbago lugging mail sacks Vince’s way, crammed with marriage proposals and romantic raves of all kinds. When Dr. Ben Casey first ventured out in public in Houston, Texas, he was mobbed by 40,000 squealing females. They swelled to 75,000 in Phoenix, Arizona. Last June his p.a. tour swept away records in a tidal wave of skirts. For girls and grandmas from Seattle to South Key, Vince has made a sour-pussed bedside manner the New Look in American medicine. At thirty-four, he suddenly finds himself a national savior-hero, sultry sex-symbol—the greatest Hollywood powerhouse since Clark Gable.

All this has undoubtedly lifted Vince from deep in the discard pile to what his stand-in, Ray Joyer, recently described as “the very pinochle of success.” It’s raised him from chronic poverty to an income of $100,000 a year, set Hollywood and Broadway producers chasing him with fabulous offers, brought him—among other things—his own recording company, stocks and bonds, a black Lincoln Continental and $25 dinners. Also a brain-fagging grind five days a week on what he calls, “The Black Hole of Calcutta”—stage 8 at Desilu Studios.

It has also brought Vince Edwards to,, another stage in his life where again he finds himself odd man, out of place and uncomfortable. By a miracle of casting, he fits the sullen image of Dr. Ben Casey like a surgeon’s glove. But in the romantic role of a Hollywood star, he’s decidedly a misfit.

Physically, Vince lacks almost nothing. “After all,” says his colleague, veteran actor Sam Jaffe, of Vince’s hypnotic effect on women, “he’s quite a hunk of man, isn’t he?” Vince certainly is. He could model for a Roman gladiator, which isn’t too far-fetched, because his ancestors were Romans. Beneath a helmet of coarse black hair sits a classic brow and a bold Roman nose, flattened slightly at the bridge by a baseball bat when he was a kid. His jaw, over which a five o’clock shadow creeps at noon, is rock-firm, with a cleft chin bracing a strong, sensual mouth. But his eyes are Vincent’s most commanding feature; they’re dark and deep enough to get lost in.

Vince’s physique is even more impressive and shows the respect he gives it. “I think my regard for my body is what kept me straight all these years,” he says. It’s a swimmer’s body thickened now by years of heavy exercise and maturity. When he peels off his shirt, the muscles stand out on his hairy arms like tree roots. His shoulders slope, punch-powered like a prizefighter’s—which is what Max Baer once tried to talk him into being, and what he once played as Joan Fontaine’s heavyweight boy friend in “Serenade.”

“Vince could have been the greatest heavyweight of them all,” believes Bennie Goldberg, himself an ex-bantam weight title contender who officiates today as the star’s valet and secretary. “Vince can go pretty good in the ring right now.” Vince goes, in the ring or with weights, regularly at the Beverly Hills Health Club, Vic Tanny’s or Goodriche’s gym—where recently, in his zeal for condition, he almost killed himself. He was lowering a 220 pound weight from above his head when his foot slipped. Vince fell on his face, the bar crashing down on top of hint. “Only the discs hitting the floor first saved him from a busted neck,” reports Ray Joyer. “He still gets a backache from it now and then.”

Another way Vince risks destruction is swimming straight out to sea until he’s invisible. He water-skis recklessly, skin-dives deep and occasionally tests his reflexes skittering his car around hairpin curves like Steve McQueen. For these feats he fuels himself with health foods—carrot juice, yogurt, wheat-germ, pineapple smeared with honey and such. His favorite dining spot is the Aware Inn, Hollywood’s temple of organically grown fare.

Backing up Vince’s animal majesty and magnetism is a considerable helping of brains. His IQ is 135. He has three years of college credits and a year at the American Academy of Dramatic Arts. He likes to delve into the modern philosophical writings of Ouspensky, Kazantzakis and Nicol. He has written several play scripts, including a symbolic fantasy. He uses almost perfect English and has nearly licked a heavy Brooklyn accent. As for acting, he has some twenty-three movie parts and as many TV shows behind him, plus work with Tony Quinn’s experimental group. “What people forget about Vince,” says Sam Jaffe, “is that he’s no green pea. He has what any star role like Ben Casey takes—experience. It gives him a great deal of ease. Also, he’s sincere and dedicated.”

Least likely to lure

Yet with all this, Vince Edwards is unquestionably the most unlikely figure ever to come up Hollywood’s king of hearts. Too often he exudes the charm of a Las Vegas gaming room cop. He seems incapable of lifting a finger to be gracious or win new friends. He’s never “on” offscreen to project a pleasing personality, which both Gable and Vince’s idol, Humphrey Bogart, could manage when they had to. Vince has no poses, pretenses, artifices or—some people believe—manners. “It would be so nice,” sighs a girl who works on “Ben Casey,” “if just once Vince opened a door for me.” His attitude toward strangers seems hostile, rude and even menacing. It’s a negative trait Vince recognizes but believes himself powerless to change.

“I can’t gladhand,” he admits. “I’m no greeter or Charlie boy. I think my own personality had a lot to do with the long time it took me to score. I could never butter up important people, not even producers who might give me a job. I still can’t.”

Right now Vince Edwards doesn’t need the jobs. But to measure up to his star rating he does need to project an attractive personal image. Unfortunately, his image is being battered in the very places where it could be made to flourish. One of these is the press.

Vince’s secretive and suspicious nature makes him a natural antagonist to reporters. The questions they fire at him, trying to open him and reveal the interesting man they suspect is in there, only strike Vince as prying. He retaliates by being cavalier, curt and diffident, cancels interviews if and when he feels like it and, when cornered, tries to confine his answers to bare facts. Usually he omits the story of his beginnings in Brooklyn. “My formative years,” he insists unrealistically, “started when I got out of there and went to college.” For a time he avoided giving his right name, Zoine, and only when undisputed public records hit print has admitted his true age, thirty-four. He still angrily resents reporters “researching” around his boyhood neighborhood. “Impressions—just impressions—what do they mean?” he growls. “I didn’t know half these people. What do they really know about me, any: way?” He’s flown into rages when reporters have interviewed his mother and other family members.

“I think,” sighed one thwarted inquisitor, “Vince Edwards wants to forget everything up to now. I think he wants to start life all over with Ben Casey.”

As a result, Vince has been unfairly taken apart in print, boobed by some writers, abandoned by others in disgust, and by still others made the subject of repetitious treatments based on the fictitious Dr. Ben Casey. By now “dour,” “surly,” “sullen” are Vince’s widespread tags and a snarl too often his trademark. Unfair or not, this is mostly Vince’s fault. Nonetheless it bugs him. Because, beneath his hard-cooked manner, he is as thin-skinned as an onion, as volatile as Vesuvius and as unpredictable as a March sky. Since Vince is Ben Casey,he sets the mood on that show with his own. “And,” says a crew member, “if Vince has just read something nice about himself, everything is rosy-dosy. But if he’s read something bad—watch out! It’s going to be a long, tough day.”

Matt Rapf, producer of “Ben Casey,” backs this up. “Ordinarily,” he reveals, “Vince gives us no trouble at all. He’s not temperamental in a classic star sense. But two things will upset him: One, if he reads something about himself he thinks is unfair. And two, when as Dr. Ben he has to say or do something Vince doesn’t believe in.

“For instance,” Rapf recalls, “we did a story about a prizefighter with a brain injury—before the Benny Paret death scandal—and the script took a stand against boxing. Vince balked. I explained why a neurosurgeon particularly would be against legal destruction but it didn’t make any difference. His attitude was that he’d offend millions of boxing fans. He’s one himself. It was a very small hassle really. A few changed lines fixed it in minutes. But Vince was pretty worked up.”

A host of Vince Edwards’ pals are fighters. “I like fighters,” he says simply. “I like their company.” One of his best friends is Rocky Marciano. Three who’ve been in the ring now work for him—Bennie Goldberg, Ray Joyer and Mickey Golden, who plays an orderly. There was a time when Vince himself was fast with his dukes.

“Sure, Vince had lots of fights,” remembers Mickey. “But he was never a brawler. Usually it was defending some underdog—or a lady. Once I saw him wade into five guys outside Schwab’s who’d insulted a passing girl. He made them apologize.” Those days are gone, but not Vince’s temper, although it’s more controlled.

“I keep clear of fights,” explains Vince. “No, I’m not afraid of bad publicity or trouble. I am afraid I’ll hurt someone. I’m big and pretty strong.”

The last time Vince saw red and acted on it was some months ago. Driving along Sunset Boulevard he saw a man whipping a boxer dog with a chain leash. Vince curbed his car, leaped out, grabbed the leash and started to give the man a dose of his own medicine. The boxer, rather ungratefully, sank his teeth in Vince’s ankle!

He hides his charms

Unfortunately, Vince could never tell a story like that on himself. He is as lock-lipped about his appealing qualities as he is about his private life and background. One is a protective fondness for all animals. Time and again he has been invited to join his pals on deer hunts. “I don’t like to kill anything,” he begs off. Cruelty to any animal anywhere makes him boil. A few weeks ago, in company with an animal trainer pal named George Fraser, Vince attended a circus near Hollywood. During the elephant act he spotted blood streaming from one elephant’s flank where the trainer’s hook bit in. “After the show,” says Fraser, “Vince was raring to go back and chew out that trainer. I finally talked him out of butting in.”

Even when Vince was hungry himself, he fed and sheltered a parade of assorted pets, including a peacock who strayed into the yard of a small house he Tented once on Lookout Mountain. “Esmerelda,” as he named it, spent three pampered months before Vince took “her” back home over the hills to Griffith Park Zoo. At the same place he was host to two lions.

George Fraser tells about that, too. “I had two lions I used on tour in a comedy routine,” he says, “but bookings petered out, I was broke and the lions were hungry. I met Vince on the parking lot at Schwab’s drug store. I had the cats in a truck but no place to keep them. Vince said, “Take them up to my place, and gave me the address. I’d just met him, understand. I didn’t know then he was about as busted as I was.”

The Rons (George, too) stayed as Vince’s guest for two months, rending the night with roars, and drawing squawks from neighbors. Police came—and an SPCA man to see if they had good treatment and meat. He found them in top condition, because Vince was spending far more to feed the lions than for himself. When the cops finally laid down the law, “Get them out of here,” they were in shape again and Vince went with George to Thousand Oaks and Jungletown to help with the act. Today George Fraser has a steady bit player’s job in “Ben Casey.”

George Fraser is only one of scores of obscure buddies Vince collected in his knockabout years in Hollywood. They make up what one calls, “Vince’s mafia.” The term is apt: Vince remains fiercely loyal, in Sicilian fashion, to anyone who has befriended him, or vice versa. Curiously, he calls himself “a loner,” which he is anything but. “Vince has more real friends in this town than any man I know,” states Mickey Golden. “Only they’re not the people you read about. He’s never lost that common touch and he never will.”

“Yeah,” chimes in Ray Joyer, who has known Vince since 1951, “I’ve been in this business thirty years and he’s the only one I’ve seen hit it who hasn’t changed one bit. The other day,” Ray relates, “we had an extra working here, whose wife was about to have a baby and mighty sick. He didn’t have a dime. Vince found out. He called me over and pressed $150 into my hand. ‘Give this to him,’ he said, ‘and if you tell him who it’s from I’ll fire you.’ Look,” Ray warms up, “see that guy up on the catwalks? They were going to let him go, but Vince heard about it. He’s still up there. And me—they said I was too short to be a stand-in. ‘If Ray doesn’t work I don’t either,’ said Vince. I’ve got big lifts I wear in my shoes, Vince’s idea.”

Mickey and Ray are natural cheerleaders for Vince Edwards, but there’s no reason to doubt them in this respect. A sign on the door of Stage 8 at Desilu: “Absolutely No Visitors,” is the biggest joke in Hollywood. Inside, the set-phone light flashes as regularly as an airport beacon. “Who?” asks Vince. “Ray? Sure, let him in. Frank? Yeah, I thought he’d be by.” A steady stream of pals from away back filters in and waits until Vince shuffles out of a take like a big, weary bear. They might be anyone from a puffy little man named Ray Burns, a tech writer with a missile firm, to Rodolfo Acosta, a rock-faced Mexican who specializes in playing Indian chiefs. Vince drapes a giant paw over the visitor’s shoulder and leads him to a dressing room with a black door labelled “Vincent Edwards,” which serves as office, sanctum, confessional and nerve center of his Hollywood life. They enter, the door closes until the assistant director starts a call rolling, “V-i-i-i-n-c-e ! Ready!” In the interim Vince Edwards has listened, weighed, judged and assured on a docket of mutually personal problems. This goes on all day and every day, often while reporters and people with business important to Vince cool their heels waiting for a precious word with him. “Vince,” sighs one affiliated observer, “operates like ward boss, or maybe a Chicago beer baron, circa Al Capone. He wants to be Papa.”

“If his friends don’t come by, Vince calls them,” says George Fraser. “He wants to know, is everything all right.”

For several months after “Ben Casey’s” instant success, Vince knit his dark brows anxiously. All of his mafia had reported except one, a Negro singer named Buddy Lucas. Vince is fond of Buddy and it hurt him that not a congratulatory chirp about his big strike had come in. Unable to bear the silence, he sent out tracers and located Buddy singing in a Miami night spot. Vince put in a call pronto. “Why haven’t you called me?” he demanded. “Why the hell didn’t you let me know where you were?” Buddy said he’d just been busy. Only when he had put that oversight to rights was Vince satisfied.

“That old gang . . .”

“Vince likes to have all these people swarming around him,” believes an associate, “because it makes him feel important. It’s a more personal and satisfying flattery than—say—a mob of fans or abstract fame.”

But Mickey Golden, who has known Vince twenty years, shakes his head. “Vince simply has great compassion because of his own background,” he believes. “He had a rough struggle himself and he knows what it means. There’s a bond. He’s like Mario Lanza, who was a real buddy to Vince. Mario was from a tough South Philadelphia neighborhood, like Vince was from Brooklyn. He cottoned to Vince the minute he met him, when Vince was fighting to pull himself up—and he gave Vince his first good movie job. Until the day Lanza died, Vince could do no wrong with Mario.”

Whatever the reason—compassion, a need for flattery, insecurity or what—Vince Edwards clings to the pals of his hard luck days, in striking contrast to almost any other big star you can name. They are his set, his social circle, from which he has expanded almost not at all since “Ben Casey” made him famous. Today, gates to more distinguished, influential and prestigious Hollywood social groups swing wide open to Vince Edwards. He has invitations to parties and musters of all kinds crowded with Hollywood’s top brass. Except for professional events—Screen Writers and Directors Guild dinners, the Academy Awards and such—he turns them down. One or several of his old gang are with him almost every waking hour at work and play. They share his most intimate confidences and he theirs.

“Should I get married?” Vince asked George Fraser recently.

“No,” George, a married man and father, replied. “It wouldn’t be fair to your wife. Right now you’re married to Ben Casey.” That’s almost true. At this point, nothing in Vince Edwards’ life can seriously compete with his labors on Stage 8 at Desilu. Vince may call it “The Black Hole,” but it’s the center of his world whose walls close out almost everything usually associated with a Hollywood star’s existence. He works there from 7 A.M. to 7 P.M., often rehearsing through the noon hour and munching an apple for lunch. Barbers trim his hair on the set; he shaves and showers between takes. Anyone who has any business with him grabs him there for catch-as-catch-can meetings—his press agent, business manager, his agent, even Bing Crosby, who produces “Ben Casey.” Throughout the long acting day Vince is in virtually every scene. “And,” points out Sam Jaffe, who plays Dr. Zorba, “we do three-fifths of a full play script every week. That means sixty pages of dialogue loaded with tongue twisting medical terms. Vince has to learn these at night.”

Vince himself says, “This job takes more guts than talent.” By the time he rolls off the Desilu lot in his black Lincoln, it’s usually dark. Then, unless he has a recording session booked until midnight, he goes to his big treat of the day—a gargantuan meal at Martoni’s, Trader Vic’s, Villa Capri or a health food feast at Aware Inn. At bis side, almost invariably, is the girl who prompts those cautious marriage thoughts with Vince—his steady, Sherry Nelson. And that’s another thing. Most bachelor actors, when they blast off to such Hollywood heights as Vince has, start swinging right out with stars, or at least starlets, for sweet publicity and to soothe a suddenly swelled ego. Vince Edwards has already swung far and wide in Hollywood—curiously not now, but when he was nobody much and in the depths of despair about ever being anybody.

Years ago the late Mario Lanza liked to drive down to State Beach in Santa Monica, stand on the sea wall and sing out in his resounding tenor, “V-i-n-c-e-n-zi-e!” A hairy Hercules would bound up from somewhere on the warm sands and shapely nymphs in brief bathing suits would scatter in all directions like coveys of quail.

“Ah, yes,” Mickey Golden, who often observed the phenomenon, recalls fondly, “there were always beautiful women around Vince. A man’s man, but a ladykiller, that he was. He was a terrific beach man, at State Beach and Muscle Beach too, but not only there. Vince was involved with plenty of starlets—and you can leave off the ‘lets.’ He dated the big ones, too.” One on his date roster was Marilyn Monroe.

Vince doesn’t deny it. “I got around pretty much in those ‘wild days,’ ” he’ll allow. “Sometimes a different actress every night. And dancers, I always liked dancers somehow. I suppose because I admire graceful, healthy bodies.” He was engaged twice, both times to dancers.

To Sherry, he’s “shy”

Sherry Nelson is neither an actress, a dancer or any kind of a Hollywood figure. “I’m just a Burbank High girl and I’ve never really done anything or been anywhere,” she laughs in a friendly, ingenuous way. A leggy blonde with a pretty face and ready smile, Sherry lives with her mother and occasionally helps out in the offices of her two brothers-in-law—both, appropriately, doctors. She has been Vince’s best girl almost exclusively for three years.

By now Sherry knows Vince about as well as any girl ever has. And to her, his outstanding trait is “a sort of shyness.” Vince is devoted to acting,” she says, “but he’d like an anonymous life if he could have it. He doesn’t like being a celebrity.”

Recently Sherry was dining with Vince at the Brown Derby when a tourist approached their booth with an autograph pad. “Aren’t you the girl who was on the Groucho Marx show last week?” he asked eagerly. Sherry said, sorry, she wasn’t, and the man drifted away. “I had to laugh,” says Sherry. “Right beside me was sitting the hottest star on television.” Far from being annoyed at the oversight, Vince only sighed in relief.

Vince explains one strong attraction Sherry Nelson has for him, thus: “Sherry likes me for what I am,” he says. “Not what I’m doing.”

Vince’s tribute to Sherry actually tells more about himself. It explains, at least in part, his clannish clinging to old friends who knew him and liked him when they had nothing to gain from him—as well as the suspicious face he shows to new ones who swarm around him now. Perhaps it is also the key to Vince’s incongruous position in Hollywood: He’d like to be Ben Casey without involving Vince Edwards. He’d like to be a star without a star’s noblesse oblige.

Almost every weekend Vince Edwards disappears when the “Ben Casey” set closes. “We don’t ask him where he goes. We don’t care, so long as he’s on the set Monday morning,” says his director. Where Vince goes—by himself or with Sherry—is as far as he can comfortably go from Hollywood and make it back. Usually it’s to the Catamaran Club in La Jolla, where he swims and dives in the coves or skis on Mission Bay. Often he makes a side trip into Mexico to watch the horses run at Caliente. Sometimes he takes a fling at Las Vegas.

Vince explains these getaways, with some justice, as necessary change and escapes from the grind of his murderous work schedule. But even when he returns, he keeps as stubbornly away from the social arena of Hollywood which most novas in his position seek to cinch their success. He doesn’t even maintain an adequate living establishment. Until a few weeks ago he roomed in the house of an “aunt” who wasn’t his aunt at all, but the mother of a one-time pal, Frank Russell, who took him in when he was broke. (Since Frank brought a hundred thousand dollar suit against Vince, the old friendship isn’t all that close.) And now Vince lives in an obscure Hollywood apartment whose address he tries to keep secret from all but a necessary few of his intimates.

These are all Vince Edwards’ attempts to divorce what he is from what he’s doing. They put him at odds with his status in Hollywood, but for him that’s nothing new. Most of his life Vince has been a stranger somewhere, eternally displaced by his drive to lift himself by what he could do from where he was and what he didn’t want to be. At college in Hawaii, on Broadway, in Hollywood, the Orient and back to Hollywood again, Vince has never fitted in. Not even in the slums of Brooklyn, where life began for Vince on July 9, 1928 in a bleak flat on a street ironically named Pleasant Place.

Vincent Edward Zoino (or Zoine, as they Americanized the spelling) was the last of seven children born to Vincent and Julia Morante Zoino; or rather he was two of the last, because he was a gemello, or twin, a fact about which, for some curious reason, Vince is touchy. “So we were hatched from the same egg—so what?” he snaps. He could hardly resent having a double of himself, two Ben Caseys at large. His twin, Robert, was not identical; he doesn’t even resemble Vince and today he’s certainly no Hollywood rival. He drives a bus.

The Zoines were a self-respecting, solid, close-knit Italian family, but painfully poor. Both parents were uneducated. Vince’s father, now dead, was a bricklayer who earned $18 a week—when he worked, which was off-and-on after Vince’s arrival on the lip of the Big Depression. The children, as they grew up, found jobs to help and so did their mother. But life was never easy; the house they moved to on Marion Street was bigger but not much better than the one on Pleasant Place. It was sweltering in summer, draughty and dark in winter.Pasta was the staple entree on the family table. It’s hard to believe now, but Vince suffered from rickets, a disease of malnutrition. Baby Vince obviously recovered early. He remembers, “I was always a sturdy kid. In school I weighed ten pounds more than my brother.” With such shaky starts, others of the Zoine brood were less lucky. Three of them—Carl, Marie and Helen—died early in life.

Vince—he kept clean!

“I grew up like most kids in a tough city neighborhood,” Vince is inclined to dismiss his boyhood. “The Blackboard Jungle and all that.” Actually, the reverse is true: Vince is where he is today because he grew up very much unlike most kids in poverty-ridden, hope-starved Flatbush. Most kids there had no ambition other than to stave off the gray tide of under-privilege that threatened to swallow them. Just to keep out of trouble, grow up, find work and follow the bare survival pattern of their parents was success. Others, rebelling, took violent paths to break out. The brawlers became prizefighters; the vicious became hoodlums. Too many of these wound up punchy derelicts or landed in places like Dannemora and Sing Sing. “I’ll bet half the guys I knew are in jail today,” sighs Vince Edwards.

But anyone who knew Vince Zoine was sure he’d never be one of those. For one thing, all the Zoines stayed clear of trouble. Poor as they were, they held their heads up. Julia Zoine kept her children neat and clean, was in touch with their schoolteachers, yanked them in off the streets to study, encouraged all of them to make something of themselves. “My mother was my greatest guide and inspiration,” says Vince, “and after her my big brother, Carl, who died so young.” Carl always told Vince, “Get an education, Vinie. Learn, learn, learn.” Vince didn’t have to be prodded much. Behind his agate brown eyes lay an inquisitive, impressionable mind.

One Sunday, when Vince was six, the Zoine family took a rare excursion into the Long Island countryside. It was the first time Vince had ever seen an expanse of trees, grass, water and blue skies. “It was a wonderland to me,” he recalls. “For a long time that sight symbolized some sort of paradise I wanted to find.” Normally his playground was the bare street where, with other neighborhood urchins, he had to dodge trucks while playing kick-the-can, stick-ball or Johnny-on-the-pony.

Vince was a leader. He was bigger than most, agile and strong. He could beat any kid chinning himself on the high bar at school playgrounds, although once he slipped and broke both arms on the paved surface. He led the pick-up teams at touch football. When he was only eleven he was husky enough for a job shovelling snow off the railroad tracks. At fourteen he could handle a man’s job excavating for the subway. But when the pack drifted off to raid fruit stands, swarm inside drug stores to hook candy bars and other loot, Vince wasn’t along. The only thing he swiped in drug stores were long solitary looks at the magazines, packing his head with facts about far away places.

“I kept away from trouble,” says Vince simply. “That’s not too easy to do where I grew up.” As he grew into his teens, traps lurked all around him. Like Harry Belafonte in Harlem, Bobby Darin in the Bronx—or any kid in a poor district crowded with school drop-outs, rejects from bad homes and charged with racial tensions—the one chilling fear that never left Vince Zoine was that somehow he’d be caught and branded before he could escape. The West Side story is an East Side story, too. Gangs roamed the streets all around Vince’s neighborhood. Murder, Inc. operated around there. Kids on his block lost their fathers to the hot seat at Sing Sing.

Older neighbors approved of Vince Zoine. “Nice, high-type kid . . . a young gentleman . . . serious . . . reserved . . . smart . . . knew he’d make it,” are how some remember him today. But at times young toughs his own age had less kind slurs . . . “Chicken . . . Sister . . . Miss Mary”—because he wouldn’t mess in their rumbles. Then there were fights. Vince didn’t lose many.

“Fights? Sure, I had plenty,” admits Vince. “In Flatbush you had to fight to survive.”

One reason Vince Edwards has no police record to haunt him is that he was almost never idle and open to temptation. He kept busy. School to Vinie Zoine was no blackboard jungle, it was opportunity. He always liked it and worked hard. In elementary P.S. 155 he skipped a grade twice. In P.S. 73, a junior high school, he skipped again. He was in East New York Vocational High at twelve. In all three places he joined every study club open to him, dragged down A’s, was invariably in the top ten of his classes. Teachers liked him, kids respected him. He held school offices, starred in sports. During his last two terms at Vocational, he practically lived after classes at the Flatbush Boys’ Club, training to swim right out of Brooklyn into a world that looked better to him even back then.

Up and out via show biz

Vince Edwards tells you today, “I think I always wanted to be an actor, even as a kid.” If so, he kept that wish locked inside him so tight it never showed through. Show business, like gang rackets and the fight game, was a quick way up and out of poverty, all right. Jackie Gleason had clowned his way to fame out of grinding poverty in Vince’s own neighborhood. Flatbush boasted plenty of famous alumni—Susan Hayward and, ages ago, the “It” girl, Clara Bow. But Vince Zoine had no contact whatever with performers unless you included the dinky horse-drawn carousel that sometimes tinkled through his street, or the itinerant organ grinder and his monkey. There was no trace of talent in his family—except perhaps his sister, Marie, who had a pretty voice and liked to sing. But Marie died early.

In the neighborhood movie houses, where Vince sat fascinated when he could scrape up the admission and spare the time, he identified himself with heroes on the screen, as all kids do, and wistfully dreamed of an exciting life like theirs. His favorite was tough, snarling Humphrey Bogart. He never appraised himself as good looking, or romantic. He seemed never to notice the giggles, glances and flouncing skirts that broke out at school or on the streets when he passed, like a dark young Apollo—165 pounds and pushing six feet when he was only thirteen.

“Girls flipped around Vince, but he never seemed to notice,” says an old schoolmate. “He was the YMCA type. Sports were everything.” Says Vince, “I never had a teenage, or really a childhood either. No time for foolishness. I was always working at something.”

At East New York Vocational. Vince worked at learning to be an aviation mechanic. After that be hoped to get a steady factory job. He was obviously college material, but how could a poor kid afford college? The Flatbush Boys’ Club answered that. Via a lifeguard at Coney Island named Sy Schlanger.

Vince had learned to swim early, at Cypress pool. He was powerful but crude. “There’s no doubt,” he says, “that I had a natural swimming talent, but it wasn’t developed.” After his sophomore year he took a lifeguard test and got a summer job at Cypress and then with Sy at Coney, lying about his age. Between dragging weekend athletes out of the surf. Sy told him, “You’ve got the makings of a great swimmer, Vince. Why don’t you join the Boys’ Club and try for the team?” Sy was already a member there and top man. He told Vince his plan: He was out to win races and a scholarship to college. Plenty of colleges were scouting the swim clubs for team material—Yale, Northwestern, Ohio State—a free ride to an education.

“For the next two years I barely dried off enough to go to school,” is the way Vince puts it. Twice he was New York State Champ in the 100-meter backstroke. Sy Schlanger got his scholarship to Ohio State. Vince applied there too and got a green light. There was only one big hitch: He lacked college entrance requirements.

At Vocational High. Vince’s schedule was heavy with shop and tech classes. To make up solid credits he moonlighted at Thomas Jefferson High. “I don’t think I ever worked so hard in my life—until now,” he muses. “I went to school—two schools—some days from 8 o’clock in the morning until 10 at night. But it was worth it.” In the fall of 1944 he left for Columbus, Ohio. He was sixteen and it was the first time he’d ever been West of the Hudson River.

THE END

—BY KIRTLEY BASKETTE

See Vince Edwards starring in ABC-TV’s “Ben Casey,” every Monday, 10 P.M. EDT.

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE NOVEMBER 1962

zoritoler imol

1 Ağustos 2023Hello there, just was aware of your blog through Google, and found that it’s really informative. I am going to be careful for brussels. I will appreciate should you continue this in future. Numerous other people shall be benefited from your writing. Cheers!