Elizabeth Taylor Is Leaving Eddie Fisher?

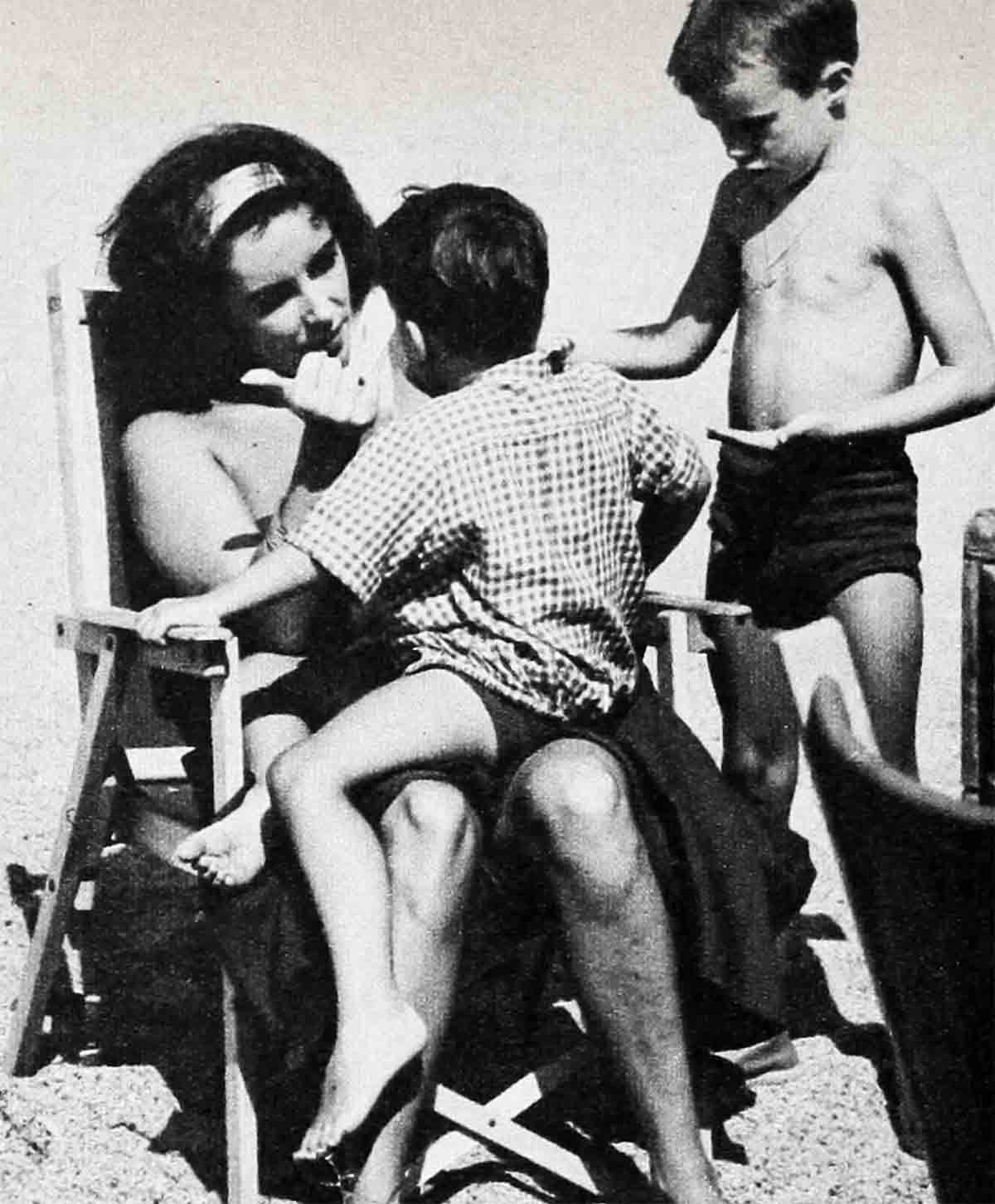

“I was on the beach near where Liz Taylor was picnicking with her boys,” said a woman who had worked with her on “Butterfield 8” in New York. “And another of those things happened that make you simply sick. It seems so unfair when people attack her through the children. Which is exactly what had happened that day on the beach.

“It was an exceptionally hot day, and Liz had taken Mike and Chris out of the city to the beach. After a while she evidently felt they were getting too much sun because she spread a blanket in a spot of shade formed by their picnic table. She got down on her knees, fixed the blanket just so and fussed a bit to make it comfortable.

“As she did, a voice came clear as a bell—you know the way voices, especially women’s, carry on the beach. ‘It makes me tired,’ the voice said, ‘the way that Liz Taylor emotes all over the place with her children. It’s corny—if she really loved them she’d stick with one husband long enough to give them a steady home. What happens to those poor kids again—now that she’s leaving Eddie?’

“I could feel the stab as if I were Liz herself,” said the woman. “Liz must have heard it, but she didn’t budge, she stayed where she was on her knees. But she looked over at her boys. I imagine she was trying to see if they’d heard, too. But how could you tell for sure?

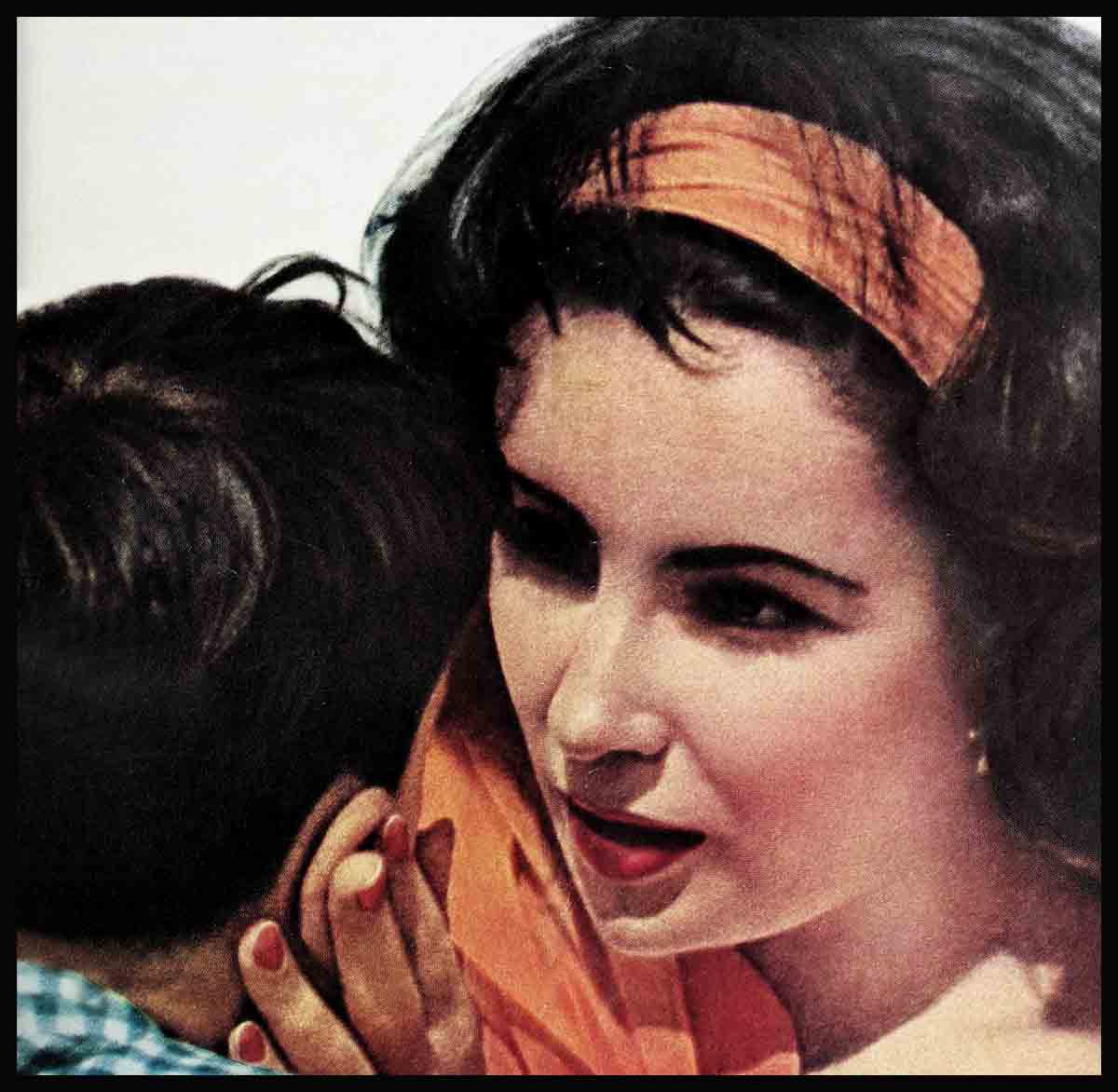

“Then the little one, Chris, came running and she got up off her knees. When he was as close to her as he could get, her arm went around him and she talked to him softly. Whatever it was, he didn’t answer, he kept his eyes down and away from her, his mouth pressed tight and unhappy. I had a feeling he’d heard every word, but he’d die before he let on.

“Liz sat down on her beach chair and lifted Chris onto her lap. She took his little face in her hands, and the way she talked, right into his eyes, she must have been trying to reassure him. By now Mike Jr. had joined them and was standing with his hand on his mother’s shoulder, listening. Naturally, I couldn’t hear and wouldn’t want to, but I could guess. Can you imagine a mother trying to tell a five and a seven-year-old, ‘Don’t you boys worry over a thing people say about Mommy and Eddie, because it isn’t so. People like to make up stories—you know, the way we make up stories at bedtime?’

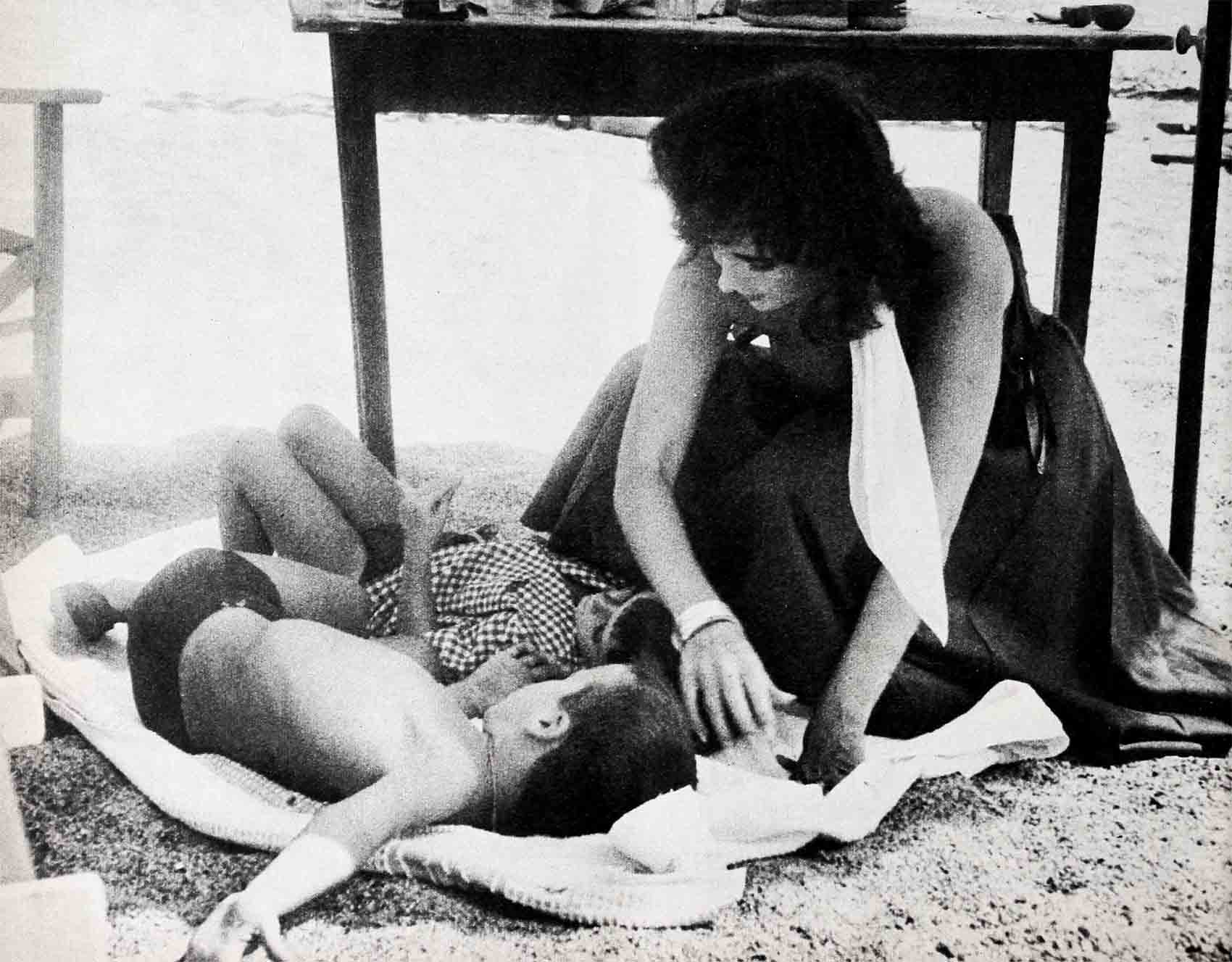

“Finally Liz coaxed them into lying down on the blanket, and they closed their eyes. She squatted down by them for a few minutes, gently stroking the hair away from their faces. Then she gave each of them one of those now-go-to-sleep-because-everything’s-fine kisses. After that she went back to her chair and sat alone, staring out at the water, right over the heads of all those hundreds of people, and she didn’t seem to see a thing.”

Liz is aware that many rumors get to her children’s ears and do a great deal of damage. Once, someone asked her how she felt about it, and she said simply, “I do my best.” She keeps the three children with her whenever it’s at all possible and when she has to be away, she phones them every day. Between calls she worries. She doesn’t want her children growing up to be troubled kids because she knows herself what it means; what that glamorous career cost. And she’s willing to give it up at a moment’s notice.

That’s why it’s silly—the rumor her career is coming between her and Eddie. Although they may be having their troubles, it can’t be blamed on this. To Liz a career has meant twenty years of work, sweat, illness and confusion. She never wanted it, she was pushed into it at eight. Her mother had been on the stage as Sara Sothern until she gave it up to marry and have children. She was determined that Liz should have what she herself had sacrificed—a career. She campaigned until she got a movie contract, and then better and better parts. She did everything, she was mother and manager. Liz was never allowed to speak for herself or think for herself or even act for herself.

Liz has never forgotten any of this. And a career that cost her so much of living doesn’t mean enough to her now that it should come between her and Eddie. If anything is pushing them apart, it’s for some other reason.

There are rumors of a growing gulf between them because Liz can’t give Eddie a baby, having already had three Caesareans, and so a fourth is forbidden by her doctor. But that couldn’t be a reason for separation. Eddie loves her children and they adore him. He plays with them, looks after them when Liz is working, he’s Daddy. Liza is too young to remember still another bond between them, but the boys might. It was Eddie—Eddie who took them to his home and cared for them when Mike Todd crashed to his death and Liz was half out of her mind with grief.

Yes, a good reason why Liz’s and Eddie’s marriage would stick is the children. She wouldn’t want them put through the wringer another time. The boys, especially, have been through it twice—when she left their real father, Michael Wilding, and when Mike Todd died. Liz would hate to do it to them again. She’s a sensitive woman, despite talk to the contrary, who has always felt their hurts as if they were in her own flesh. Right from the start. Soon after Mike Jr. was born, a reporter once asked her how she was getting along as a mother. She raised weary eyes in a peaked face and said, simply, “When he cries, I cry.”

A meeting of strangers

Knowing how her children feel about Eddie, Liz wouldn’t want to put a wide gap between them as there is between the boys and their real father. She hasn’t forgotten the time she and Eddie were in England with Mike and Chris, and Michael Wilding wanted to see his sons. So the Fishers invited the Wildings—Michael and his present wife Susan—to dinner at the place where they were living during their stay.

As it turned out, no one of the four around the table felt relaxed, the conversation was superficial small talk, and it was almost a relief when, after dinner, the boys were brought in to have a visit with their father. What happened next was seen and described by a British chauffeur who drove for the Fishers while they were in England, and to whom the children had become very devoted.

“The boys came in, already in their pajamas for the night,” he said. “They didn’t run to their father to be hugged and kissed, they walked over to him and shook hands like little gentlemen. He asked them how they were, they said they were fine, and then nobody seemed to have anything more to talk about. The boys stood around stiff and helpless, they didn’t seem to know what was expected of them and what to do next. I never saw two more uncomfortable children. It was like a meeting of strangers, not of father and sons.

“Finally Mrs. Fisher got them out of the situation. She kissed the boys and said, ‘All right, children, bedtime, say goodnight now.’ They shook hands with their father again, and went off to bed. I can’t remember seeing a more strained evening in my life.”

Liz has not forgotten it either. And the kids are a bond between her and Eddie—not a gulf. If something is wrong, it’s because of Eddie and Liz—nobody else. But to understand how such rumors start, you have to understand Liz.

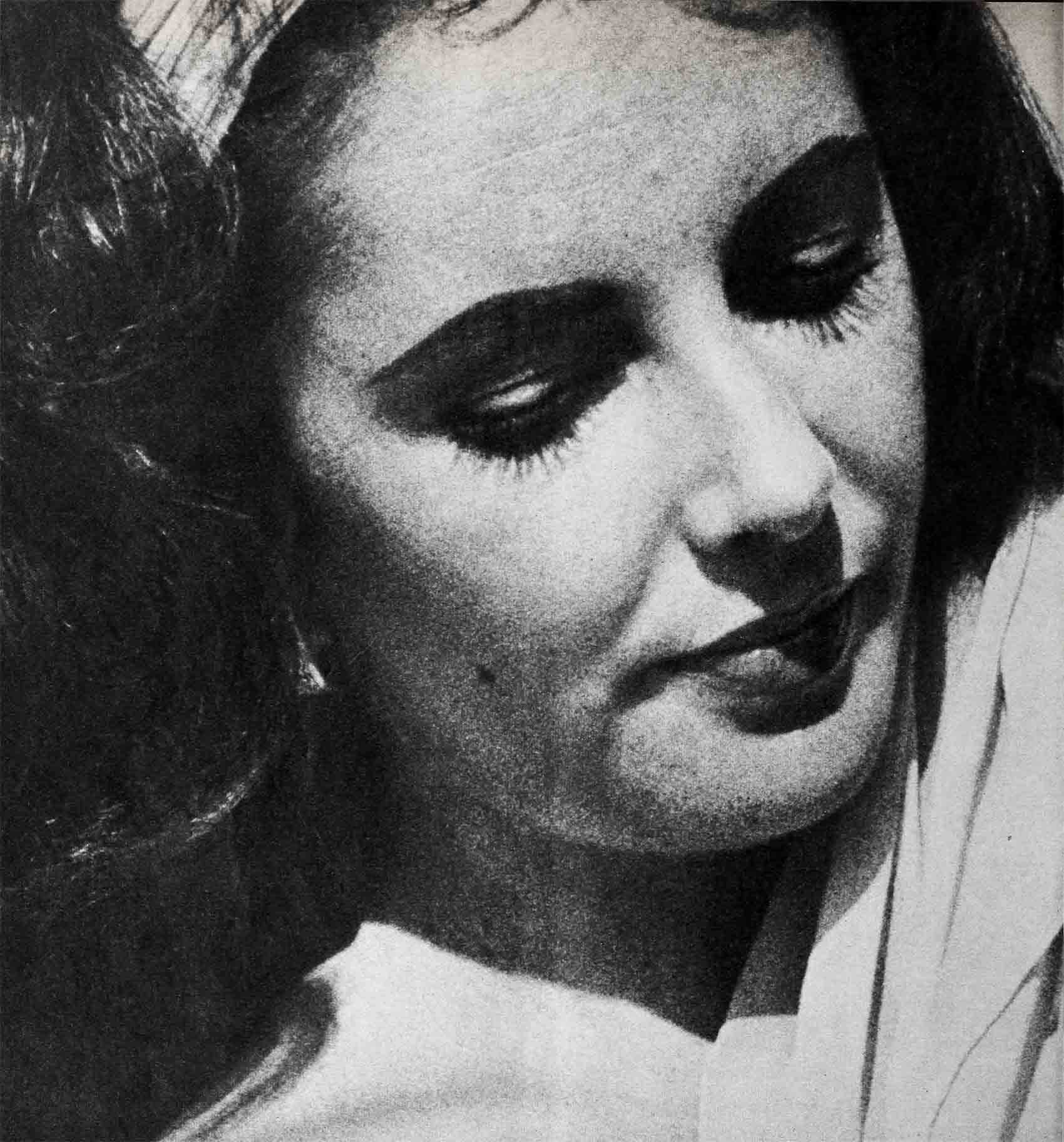

Liz has been accused of being moody, cold and selfish . . . partly because she won’t try to explain her actions. Sometimes she acts like a little girl—she has a whooping, little girl’s laugh—and then sometimes she’ll walk on the set, eyes straight ahead and not looking at anybody, like a queen. When not in costume, she comes wearing very tight jersey toreador pants in wild colors—yellow or green or orange—with a polo shirt, while in the evening she’s dressed to the hilt in plunging neckline. For daytime, she likes a kerchief of some bright wild color. She wears little makeup and looks like a little girl. She may look as though she has a lot of makeup on, but she doesn’t really. She looks like she wears a lot of eye makeup but that’s the way her eyes look naturally. And she eats constantly, mostly in her dressing room rather than in the commissary with the rest of the crew and will have special food brought in for her. She’ll have an enormous lunch, then have a three o’clock snack of something like pizza or chili; next day she may prefer champagne—nobody can guess what it’ll be the next day. If Liz’s mercurial change ever bothers Eddie, he’s not mentioned it to anybody.

On set, she sits alone, looks bored, continually chews on the inside of her cheek nervously. She looks as though she wants to reach out to people and she always lights up and looks grateful and interested when they do talk to her. But she’ll never be the first to start a conversation. It’s also true, though, that the people around her seem to want to discourage people from talking to her. But more than that, it’s almost as if she were afraid of offering her friendship to a human being and having it used against her later, so she lavishes her feelings on animals. One day she came on the set bringing her two puppies, Gittel (Gittel is the character she’ll play in “Two for the Seesaw”) and Schlermie. She seemed satisfied to sit there quietly, saying nothing, but just stroking the puppies.

“If you don’t talk to her first, she can go for hours, even sitting right next to you,” one of her co-actors said, “without saying a word.” When someone remarked it was a nice day, her answer was, “a nice day for anything but working.”

Eddie’s career comes first

She seems to think she’d like to retire and talks about it but would probably be bored without acting, although how would she know since she’s been working since she was eight, and is a real pro as an actress, never ever fluffing a line? But she makes no bones about it, Eddie’s career comes first.

The day they were shooting Eddie’s first scene in “Butterfield 8,” she was so nervous, she did fluff. She kept staring at him anxiously, even mouthing his lines. This was the day she’d been looking forward to for a long time. Earlier in the picture’s shooting, when someone had asked her when Eddie would start, she knew the exact date, though it was three months away. When, what with the delays, he didn’t start till even later this only added to her anxiety.

“When the day finally arrived,” one of the “Butterfield 8” crew said, “she was on pins and needles.” Few people know that she made a stipulation that Eddie’s company is to record all the background music on her films, like her next, “Cleopatra,” and together they have formed their own production company. The bits of gossip that Eddie resents her pushing, dislikes her working, feels her talent and career outstrip him seem, at least from the outside looking in, completely un-founded.

When Eddie comes on the set, Liz’s face lights up when she sees him. They greet each other loudly—hi, darling—and kiss, almost as if to show people their marriage s all right. But they do look, in fairness, in love. When Eddie was away on the Coast, Liz was ill—when he returned, she immediately seemed better. On the set, she is always introduced as Mrs. Fisher, although the crew calls her Liz and Eddie calls her honey or darling.

She acts like a little girl with him and seems to defer to his wishes—not Eddie to hers. Once, on location on Fifth Avenue, about a dozen people were trying to decide where to go to eat and they asked Liz, deciding to go wherever she wanted. She immediately turned to Eddie and asked what he’d like to do. And Eddie decided. He is not as boyish as he used to be and seems to be trying to assert himself, a la Mike Todd, when he’s with Liz. He’ll clown around loudly, jokingly shout orders to people and always gives the impression that he’s the boss in the family.

Her joining the Jewish faith was a sincere act and whenever anyone, like the director, made a point of making Jewish jokes, she got a big kick out of it. If someone used a Jewish word, she’d always say, “What is it? What does it mean?” She seemed very anxious to learn them. And occasionally, she’d use a Jewish word herself, like saying her Mishpochah (family) were all in town when Eddie’s mother was in New York. In a way, it seems she wanted to please Eddie.

There seemed to be no feeling against Liz from the crew or the cast because of marrying Eddie. At Stony Point, N. Y., when Eddie arrived on location and she kissed him in front of 200 townspeople, they all clapped. Yet, Liz knows every time people see her and Eddie what they’re thinking. One day, early in production, almost as a relief to break the tension she sang, out of the blue, “Tam-my, Ta-a-mmy, Tammy’s in love. . . .” It was as though she wanted to say, I know what you think, but I would rather we all brought it out in the open.

Liz’s illness has been the center of much talk. Every time she’s not happy, she gets ill—the rumors run. And she’s never felt worse than the past six months. Trouble? “Certainly, between her and Eddie,” people insisted. “It’s an emotional reaction—she’s not sick. She’s temperamental.”

But those who worked with her on “Butterfield 8” confirm that she was ill. That any temperament comes from illness rather than the other way around.

Like the day she was supposed to have walked off the set in a huff. Liz has a mind of her own on the set and will make suggestions and give her own ideas to the director, but one has to admit she does work well with people, is friends with the crew. She never asks for special camera shots or lighting to, say, hide the fact that she’s overweight. She is overweight and she knows it. In one scene, she was supposed to be picked up and lifted onto a bar. Worriedly, she asked her co-actor, “Are you sure I’m not too heavy for you?”

The day she let temperament fly she was ill. She was upstairs in her dressing room, something like a half-hour late coming onto the set. Director Daniel Mann sent the assistant director to see when she’d be coming down, and she said right away. She had pains in her stomach. Later, after an hour or so, another messenger asked when she’d be down. More time passed and finally Mann went up himself. “Either we do it or we don’t,” he said, meaning the picture. She said, “Maybe we won’t.” There were more words and finally she started to cry. It’s true, she had been late and out sick a great deal, but this was the only blow-up. She had been very ill all through the picture—stomach pains (eating too much? tight costume?) trouble with her back (can’t stand or sit in one position for too long—must rest) . . . injured leg . . . throat is hoarse (can’t speak). On her wedding anniversary, Eddie had planned a surprise party on the set and had ordered a cake for 40 people. But that day she was sick and didn’t work. There was no doubt that she had hurt her leg when she fell on the ice; that she’d had repeated operations on her spine and that her throat did give her trouble, no doubt aggravated by fatigue and complicated by strenuous dieting. If there were small tensions, as people reported, between her and Eddie, there were also tensions with her work, but these could be traced directly to physical discomfort.

She obeyed but never forgot

Crowds congregate to stare at her whenever she’s on location. So she is very careful not to bring the children to the set. This is not part of a child’s world, she feels, and who would know that better.

She has never forgotten her mother standing in some inconspicuous spot behind the camera, where the director couldn’t see what she was up to, and giving out hand signals for the girl to follow. They were very subtle little reminders that she was forgetting what Mother had taught her. Anyone glancing at Mrs. Taylor might merely see her touch a finger to her neck as if she had a momentary itch. But to the harassed child on the stage, trying to watch her director but knowing she must also watch Mama, that touch was code for “Elizabeth, you’re overdoing this scene. You’re hamming.” If Mother’s hand touched her blouse over the heart it meant “Show more feeling, Elizabeth.” Finger to cheek, as if deep in thought, warned the child, “You’re not smiling enough.”

Liz obeyed, but she has never forgotten. And another remembrance she’ll never lose is how an old family friend once stuck her neck out trying to fight for the girl’s right to grow up and get an education. From eight years, right through high school age, Liz had gone to school on the studio lot. It meant working on stage every morning, studying in any odd corner whenever she had a free minute between takes, and going to class every afternoon. “If you felt like daydreaming,” Liz remembers, “you had to go to the girls’ room.” But if she liked a subject, like English composition, she got A’s in it. So when she got her high school diploma from the studio school, her mother’s old friend went to bat for Liz.

She came to Mrs. Taylor and said, “Sara, this girl has a fine mind and wants to develop it, she wants to be educated. I think you ought to let her go to U.C.L.A. or some other college. She ought to be more among young people her own age—and more on her own.”

The girl listened breathlessly. Going to college would mean learning a lot. And it would also mean freedom. Maybe she could finally get to pick her own clothes, and even her own dates, instead of having Mama choose her wardrobe and screening every boy who wanted to take her out. So she hung on the answer.

But it wasn’t yes. Mrs. Taylor looked her friend squarely in the eyes and said, “Nonsense! I bet all those girls at—wish they were Elizabeth Taylor.”

Whether Liz Taylor wishes she was Liz Taylor is another matter. She never says. But, right now, despite gossip, rumors and jobs, Liz Taylor does wish to be Mrs. Eddie Fisher. This she will say.

—BY JULIA CORBIN

SEE LIZ AND EDDIE IN M-G-M’S “BUTTERFIELD 8.” WATCH FOR LIZ IN 20TH’S “CLEOPATRA.” HEAR EDDIE RECORD ON THE RAMROD LABEL.

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE OCTOBER 1960