“Mommy, I’d Like A Brother Or Sister.”—Jayne Mansfield

I used to be very sorry for myself, and all because I was an only child. I might still be—if it hadn’t been for that hot summer evening in Dallas, Texas, when I was eight. But I’m getting ahead of the story. Because my story really starts five years before, when I was only three—and it dates back to a night on the highway leading into Philipsburg, New Jersey. I remember it very hazily, because I was just three, but that was the night I first felt loneliness . . .

We were coming back from a visit with relatives. Daddy was driving, as usual. He was a young man, just thirty at his last birthday. Handsome, too. And so kind. We were pulling around a curve about forty miles from town when he suddenly collapsed.

If Mother hadn’t grabbed the wheel, we would have crashed. She managed to pull the car over to the a side of the road, bring us to a safe stop, and turn off the ignition.

But Daddy was dead. He had died of a heart attack.

At three, a child’s reasoning, like her love, is not rational. At the funeral, which I hardly remember, I cried because I loved him, and he would no longer be with me. It took several years till I realized I would never have the brother or sister I had wanted so badly. Even after Mother remarried, when I was six, she had no more children.

This feeling of being alone, the envy of watching other children play with their brothers and sisters, of envying even their quarrels grew into a constant, underlying feeling of discontent and self pity. Yet it didn’t really break to the surface till that summer day in Dallas.

I had been playing jacks with Tessie Malone, e freckle-faced, usually good-humored little neighbor girl whom I had known since we moved into the street. When I kept winning, Tessie got annoyed. Finally she cried out. “Go home. I don’t want to play with you anymore. I want to play with my sister . . .”

“But what will Ido . . .?”

“I don’t care. Leave me alone. Go home. . . .”

On the “way back I passed the Leutweilers’ house, near ours. I played with Jackie and Walter and Gale almost every day, but this afternoon they weren’t on the porch. I took a chance and rang the bell.

Mrs. Leutweiler, tall, stately, kind and firm, opened the door.

“Could Jackie and Gale come over?” I asked.

“Not today, Jayne. They’ve been bad children. They’re being staying home . . .”

I hesitated. “May I come in and play with them here?”

“No, Jayne. They’re being punished today.”

When I passed their window, I overheard their giggling inside their rooms. That’s being punished? I thought, disappointedly. I would have liked to get punished too if it meant having such a good time.

A dog isn’t enough

I sauntered on home, slowly, aimlessly. Mamma was out when I walked into my house. Corky, my wire-haired terrier enthusiastically wagged his tail, but I didn’t want just a dog to play with.

I don’t know how long I sat on my bed, not knowing what to do except feel sorry for myself. Finally I took all my belongings out of my drawers, walked to the five and ten, bought two rolls of shelf paper, came back and lined all the drawers before putting back my clothes and knick-knacks, just to have something to do. Then I sat down and stared at the ceiling . . .

At the Leutweiler house Jackie and Gale had sat out their punishment. My face brightened with anticipation as I saw them head for my home. They didn’t stop. . . .

“Where are you going?” I shouted, breathless from having dashed out of my room, down the hall, and through the living room to the front door, but trying to be very casual about it.

“To the movies,” said Jackie.

“May I come along?”

They went into a huddle. Then Gale looked up. “Naw. We want to be alone. Why don’t you get your own sister to play with.

Run-away

I ran into my room, slammed the door, flew onto my bed and buried my face in my hands. That’s how my Mother found me when she got back from the store.

Her voice was soft, her hands caressed my head, neck, and shoulders. “What’s wrong, darling?”

“Nothing,” I cried out. “Nothing! Nothing at all! Just leave me alone!”

I didn’t have tantrums very often, so this worried Mother.

Tm still not sure why I blew my top on this particular day, except maybe it was so hot and so many different things happened within a few hours.

By dinnertime I had calmed down somewhat. I noticed Mamma and my stepfather exchanging glances. I knew she must have told him, but he too said nothing about it.

After dinner I went back to my room, picked up my favorite doll, and cuddled it in my arms. “You’re my sister,” I said. “I do have a sister, I do, I do, I do. . . .”

I had done this often before. Only this night I just didn’t feel like playing make-believe. My ‘sister’ was just a piece of plastic dressed in cloth.

Suddenly I knew what I had to do. . . .

Mother was drying the dishes and my stepfather reading the paper when I sneaked quietly out of the house. In my right hand I carried a small suitcase into which I had hastily thrown my toothbrush, nightie, slippers, and piggy bank. In my left I held my winter coat in spite of the ninety-some degree heat even after dark.

I didn’t know where I was heading. I just wanted to get away. As long as I had no brother or sister, I reasoned, I might as well be all alone.

I wasn’t for long.

About a half a mile from the house I could hear the patter of paws and the hard, exhausted breath of a dog. A few seconds later Corky caught up with me, and licked my hand. Now I really bawled.

I was still crying when I limped back into the house. Mother didn’t even know I had left, for all in all I was gone just a little while. And when she saw me, she didn’t scold, didn’t ask for an explanation. She just sat down next to me, put her arm around my shoulders, and drew me close. She was crying too. . . .

“I’m sorry, Mamma,” I sobbed. “It’s just. . . .”

I didn’t know how to say it. I didn’t have to. She knew. . . .

“Jackie and Gale didn’t want to take you to a movie, did they?” she asked softly.

I nodded my head.

“And Tessie sent you home . . .”

I nodded again.

Feeling sorry for herself

“And you feel sorry because you have no brother or sister of your own, and you envy the other children who do, isn’t that it, Jaynie?”

“Yes Mom. . . .”

“Have you ever thought that they might envy you too in some ways . . . ?”

It had never occurred to me.

“Do Gale and Jackie have their own room, like you do?”

“No, they don’t.” My face brightened as I perked up. “But you know, they’ve often said they wished they did . . .”

“And didn’t I hear Tessie say the other day she wished she could have a dog, like Corky, but that her father insisted if he gave her one, he’d have to get pets for her sisters and older brother as well, and he couldn’t afford to keep that many around the house. . . .?”

“She did.”

“And do you know that we might not have been able to let you take violin and acting lessons if you weren’t an only child?”

I had to admit she was right again. And Mother hadn’t even brushed the surface. . . .

As the days and weeks and months went by, I began to appreciate more and more the advantages of being an only child, and I wasn’t just thinking of things like having my own room, and desk, and vanity set, and the prettiest dresses of any girl in class.

I realized how Mother had given up her bridge games to take me to my drama lessons; how my stepfather had always arranged to take me along on his business trips; and while he talked to his clients, how Mother took the place of my teacher by going through my lessons with me; how both constantly and joyfully arranged their lives to give me the best education and best opportunities and the many little luxuries I could never have enjoyed if they had to be shared between two or more children.

My home too

“I don’t want to,” I had replied. “I want to do something creative. Why can’t I sketch?”

“Planting roses can be very creative,” Mother had smiled. “And besides, this is your house as much as ours, and is should be a privilege to help beautify it don’t you think?”

I didn’t think so. At least not till a rose bloomed and I brought all my friends over and cried out, “Isn’t that the most beautiful flower you’ve ever seen?”

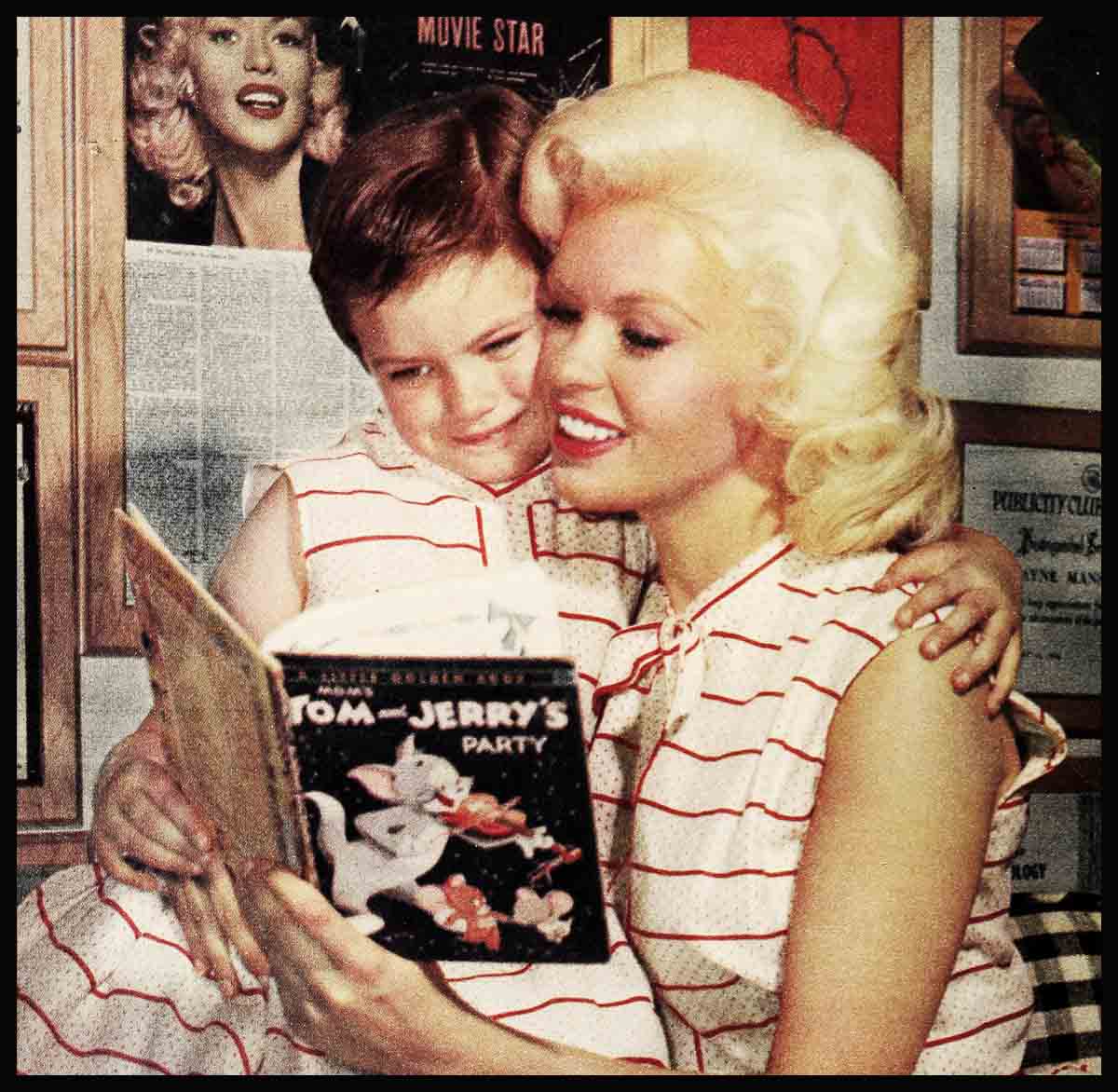

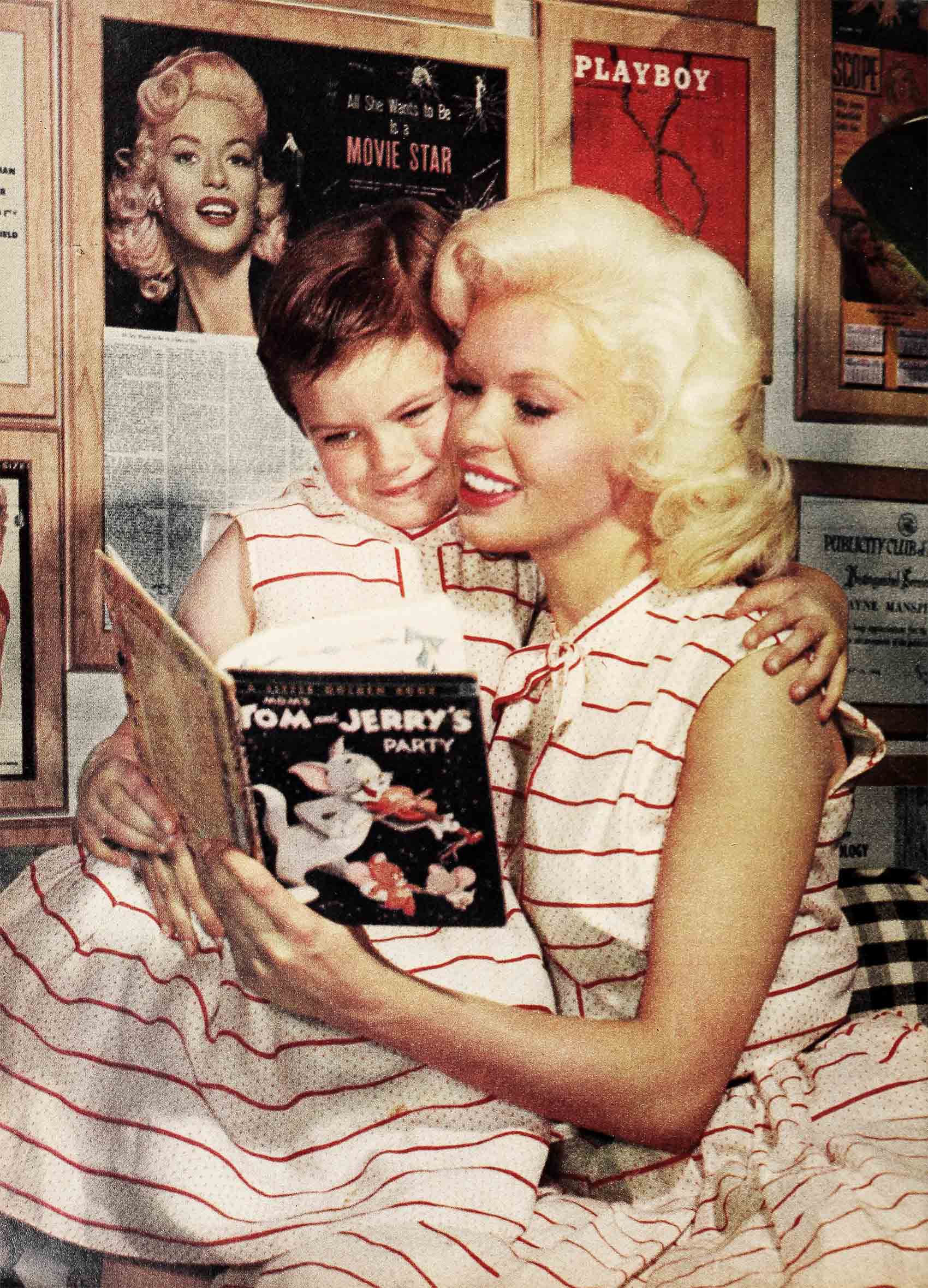

Today I am convinced that the day in Dallas when I realized how fortunate really was not only helped me grow up more happily, but helps me rear my own daughter. Jayne Marie, also an only child.

Had my feeling of loneliness and self-pity persisted, I couldn’t have kept he from feeling exactly the same way. A it is, by remembering my own childhood and my parents’ wonderful attitude I can help her be a happier, better adjusted child as well.

Just a few weeks ago, for instance, she was sitting on the pool deck, dangling her feet in the crystal-clear water, her mind miles away. “Mommie,” she announce finally, “some day I’d like to have a brother or sister. . . .”

“You will,” I assured her, “and I hope soon. . . .”

She wasn’t satisfied. “Some days I just don’t know what to do all by myself Like today . . .”

“I’ll tell you what you can do: you can help Mickey and me carry bricks up from the street to the patio so he can finish the terrace . . .” and with that got up from my lawn chair.

“But Mommie,” she cried out. “Why should I carry bricks? I’ll get tired. . . .

“Not if you take one at a time. Besides, this is your home as much as mine and the patio we build will also be your as much as mine . . .”

“It will?”

“It most certainly will,” I assured he as I headed down the steps to the road where Mickey was already unloading the truck parked in front of the house.

Jayne Marie soon joined us. She was tired that night, when we stopped. But she was happy and she didn’t comment again on being lonely, or an only child. And I didn’t feel sorry for her any more than my mother did for me when I was her age—because I had learned that there’s really nothing to be sorry about. . . .

THE END

See Jayne in 20th Century-Fox’s WILL SUCCESS SPOIL ROCK HUNTER?

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE DECEMBER 1957