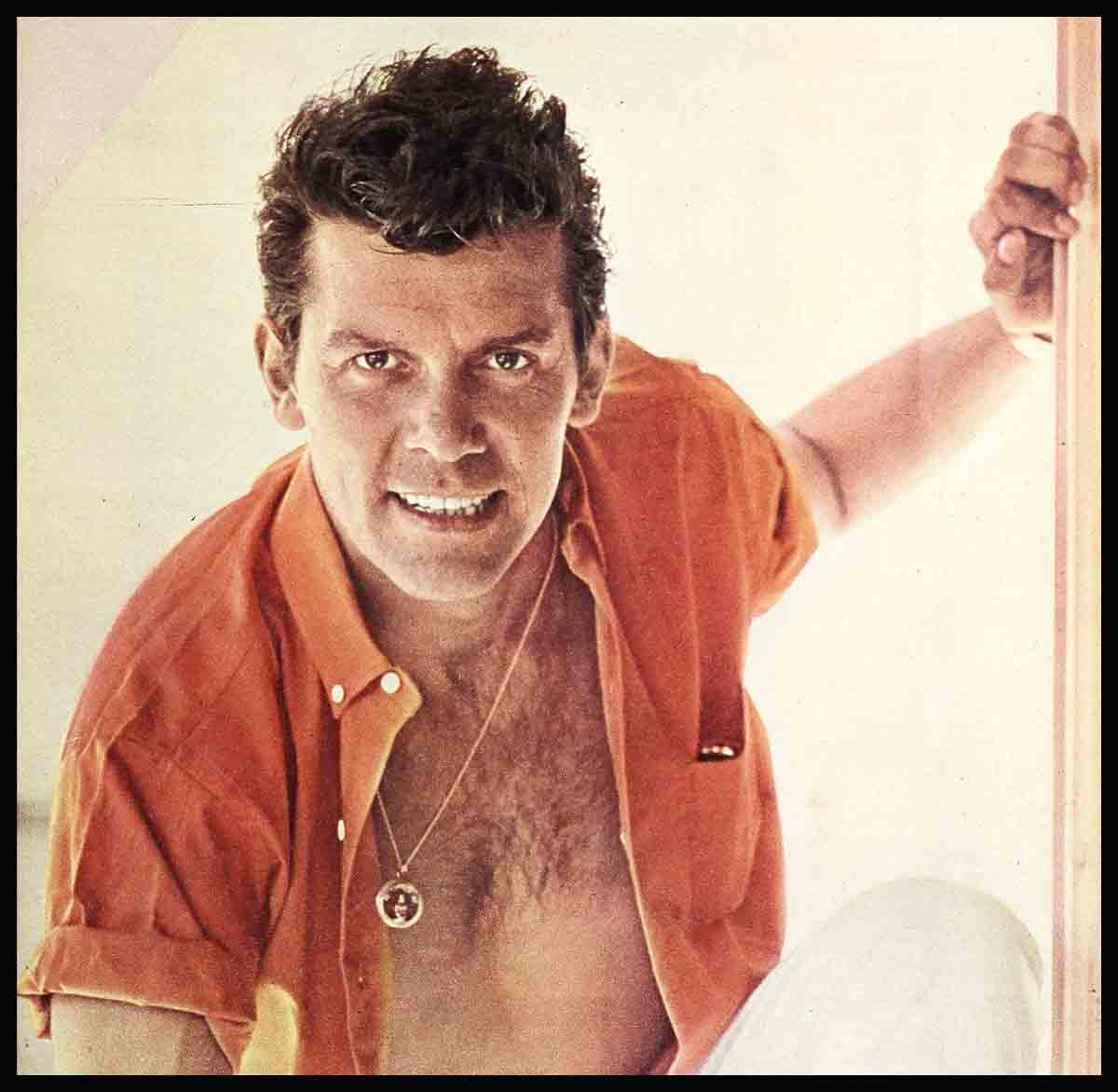

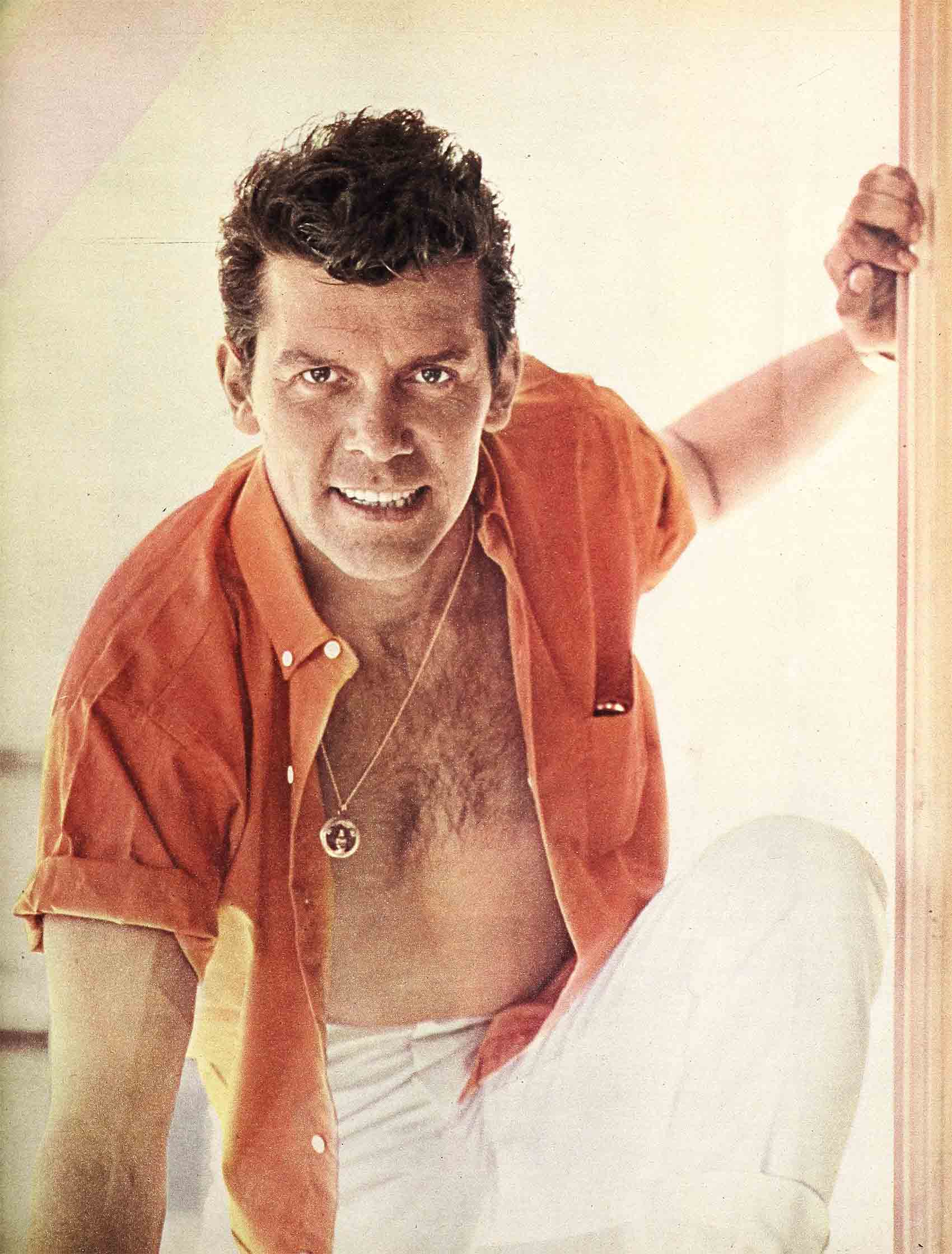

Lee Patterson

Lee Patterson. A new name. A new star. A strange guy. Legends— incredible legends —collect around him. Even his myths have myths. Not since Yul Brynner has an actor worked so hard to wrap mystery around himself like a magician’s cloak. Watch!

Myth 1: He’s at a night club with a girl. A stranger tries to move in on his date. Lee edges the fellow out. “See here, old buddy, do you mind ? This lovely lady’s my wife.”

Result: The word is out—Lee is married.

Myth 2: It’s another day, another girl. He’s taken her and six London youngsters on a charity outing— he’s a do-gooder at heart. . . . A friend runs into them. “Isn’t it amazing?” Lee asks the friend. “Half the children look like me, and half like my wife.”

Result: Lee is married and has six kids!

Myth 3: He’s at a party—brooding darkly into his glass. “And then,” he confides, “there was a hideous moment . . .” “Ah, poor Patterson,” go the whispers. “Imagine, his wife and children wiped out by a wartime tragedy.”

Result: Lee Patterson is now a widower.

Myth 4: He’s walking down the street. One passerby murmurs to another, “That’s Lee Patterson. Do you know that isn’t his real face at all? Every inch was rebuilt by plastic surgery . . .”

Myth 5: He’s in a roomful of people. Without warning, he drops like a corpse—full length, face forward. But before he hits the floor, his arms are out and he’s doing perfectly timed push-ups.

“Did you know,” goes the buzz, “that he trained Israeli Commandos against the Arabs? He’s an underground fighter . . .”

Legend-making at thirty-two is precocious stuff. But the wiry, curly-haired costar of “SurfSide Six” is no wet-eared kid. Many of the myths are triggered by his own sardonic outlook on life. They rise out of his seething anger, his running war with the world and with himself. It is one way of getting the last laugh—by imprudently mocking the mockery of life.

The truth scrambled

His myths are a scramble of truth and fantasy. They mirror his own whirling conflict. Some of them are pure hoax. Some are products of innocent misunderstanding. Some have just enough substance to offer unexpected peeks under the mask that most men wear.

Take myth number three. It’s a Lee Patterson catch-all. His life has been full of hideous moments. He could have been referring to any one of scores. But there is no accounting for the wild rumor that he lost his wife and children in a wartime tragedy.

Perhaps at some memory-blurring cocktail party, with his imagination turned loose by a little fire water, Lee said something like that just to see how much people are willing to believe. Fantasy, after all, is an actor’s prerogative. Or perhaps it was all a case of mistaken identity.

“They say everybody has a double,” he grins. “I must have ten of them.”

But he also insists he’s never been married, and never has fathered any children that he knows of. There’s nothing to do but take his word for it.

Myth four at least has a hook to hang its hat on. Before Lee emigrated to Hollywood he was a tireless swinger—as well as an incurable kidder—on the continent. He made the scene at Cannes, Paris, Rome, Berlin and Madrid. On a holiday in the south of France a truck rammed the rear of his sports car. Lee climbed out with a gash in the back of his head. Three stitches repaired the damage. But by the time he got back to London, the story had taken off on wings of fancy. His three piddling stitches were embroidered into a full face restoration.

Myth five pulls forth a riddle within a riddle. Time and circumstance suggest that Lee couldn’t have been in the right neighborhood at the right time to have been an underground fighter training Israeli commandos. When he told this tale of derring-do at a Hollywood cocktail party, it may have been the Walter Mitty in him talking—or a forgotten movie role come to life. But it’s true that because of his own troubled childhood, he has always identified with the underdog. His sympathy for the plight of the Jewish people, and his admiration for their homeland, are genuinely felt. When he made pictures in Italy, he would fly to Israel, weekends, to do the night clubs there. Maybe it would have pleased him better if he were a warrior, rather than a reveler, in Israel.

The man and the legend remain unfathomable. That is part of the mystery—and the strange charm—of Lee Patterson. You wonder about him—and guess at what you can’t know.

This is no myth

But his reputation for a withering tongue is no myth. He rises in full scorn to the slightest bait of sham and idiocy. At a London cocktail party one afternoon, an opinionated English producer was denouncing an actress friend of Lee’s who had just tried to kill herself—reasons undisclosed. Lee grabbed the oaf by his lapels and told him through clenched teeth, “Listen! You’ve been moneyed up to your bloody ears all your life, and you don’t know what it is to suffer. I’ve got one thing to say to you, Buster: If you ever attempt suicide, I hope to hell you make it.”

Early in Lee’s moviemaking career in London, a naive reporter picked up a juicy rumor going around the pub circuit and asked Lee pointblank if he really was a deserter from the American Army.

“Of course,” Lee snapped. “That’s why I’m trying to get my face on the screen all over the world—so nobody can see me.”

In Hollywood he is a loner, a pub-dodging bachelor who putters around his spanking new two-bar, two-bath and two-bedroom split-level home.

He is discreet about his conquests. Actresses are anathema to him, and he isn’t bashful about stating the reasons.

“It puts me right off, the minute a woman has a career,” he admits bluntly. “I can’t look at her as a woman. Nothing clicks. I’m spoiled rotten because I’ve been with women whose only thing in their lives is the man. Every breath you take, every move you make. And boy, when you’ve gone that route, and you’ve had the best like that, the other doesn’t mean a helluva lot. You’ve acquired a taste.”

An interesting blend. Pampered by women—roughhoused by life.

Lee Patterson fits a deceptively familiar Hollywood mold. He’s tall, dark and handsome. He’s a rangy six foot three. His jet eyebrows accent a deeply sunbronzed face drawn tautly over high cheekbones. His black, wavy hair is something that bosomy starlets dream of running lonely fingers through. He looks at the world through sometimes mournful brown eyes, and he is also adorned by a straight nose and a warm mouth that turns up in an appealing, sometimes unsettlingly gent!e smile.

Behind the good looks, the myths and the repartee. is the man. Troubled. Needing. Masking uncertainty with clever talk. Running from life. Searching desperately to find it. Comforted in the bosom of love—yet backing away from it in distrust bred from childhood.

In London, Lee lost himself in a tempestuous love affair with a beautiful Scotch-Lithuanian girl. She was a natural platinum-blond model who did nothing about her acting aspirations. because professional ambition died when she was in Lee’s arms. For three years he loved her as he has loved no other woman—but he turned her away. He was bedeviled by fear—fear of what he would do, fear of what she would do. He tries to dismiss it as yesterday’s news, but he can’t. She’s still in his blood.

“It was a big thing, a big sex thing, a big everything.” he nods. “There were about ten other times I thought I was in love, but boy, after that, you know that you don’t know anything. After that big one, all the rest are written off.”

Trouble in paradise

Their paradise was repeatedly invaded by trouble. Once, by accident, Lee found out that his girl was in tax trouble with the government. He was furious with her.

“In heaven’s name, why didn’t you tell me?” He grabbed her by the shoulders. “What am I—a stranger or something? You ought to know by now that I’m the sort of person who has to know everything. Trouble or anything doesn’t scare me a bit. But not knowing does. I must know everything about you—everything. The way you think. Every little thing you do when I’m not with you. I cannot find out from somebody else. I must know, because I can’t handle it otherwise.”

He alternately shook her and swept her up in his arms. He kissed her in one breath and upbraided her in the next. She trembled in the storm of his torment, tears burning searing rivulets down her cheeks.

“But I wasn’t trying to deceive you,” she wept. “I didn’t want to worry you. It’s because I love you so much that I didn’t tell you. Why can’t you believe me?”

She was right. He couldn’t believe her. He wanted to—so hard that it twisted him into knots. But he couldn’t. His jealousy wouldn’t let him—nor her beauty, nor her secrecy.

He kept telling himself that everything would be all right. Only he kept digging for secrets, and eventually he would find them. If it wasn’t taxes, it was—other men. The real knock-down-and-dragger-outer came when he returned from film location in Italy.

After a reunion that was heady with love he asked, “Well, darling, what did you do while I was gone? How’d you keep yourself busy? Where’d you go? Who’d you go out with?”

“Oh, nobody,” she said, kissing him gently on the lips. “I stayed in every night.”

“But that’s so foolish, honey,” he protested.

She put an affectionately silencing finger across his mouth.

“I’d rather be lonely than bored. When I’m lonely there’s only room to think of you.”

In the weeks to come, he learned otherwise. She had gone out with other men. He tried to overlook it, but it ate away at him.

“Why?” he yelled. “Why couldn’t you be honest about it? Why did you have to lie? Why did I have to find out from someone else? Don’t you know it destroys me? Is that what you’re trying to do?”

She threw her arms around his neck and sobbed. He pulled them away, and she flung them back desperately.

“Lee, why can’t you understand?” she pleaded. “Why won’t you understand? Try to be reasonable. Look at the rage you’re in now. What would have happened if I had told you? I couldn’t tell you. Don’t you see? I couldn’t. I was afraid I would lose you.”

He tore himself away from her, and shook his head helplessly.

“. . . the way to lose me. . .”

“Don’t you know that’s the best way of losing me?” he cried. “If you’d told me you’d gone out, okay. But if you hide it from me, what am I going to think? The worst!”

And thinking the worst, in agonizing heartbreak, he quit the one woman he loved. The wound still bleeds fresh, and he talks as if it happened an hour ago.

“I’m not saying that she was fooling around,” he still debates in his own mind. “And if she was, what could I do about it? You hope to God that if you’re the right sort of man you can hold a woman. And if you can’t, then you’re lacking in yourself. You can be manly as hell and some of them still have to go their way.”

So they’d fought over what they couldn’t change—just as his mother and father used to. When that hit him, in the full flush of panic, when it suddenly put him back in his childhood, and he could see his parents at each other’s throat every misery-filled day—that was when he ran from the one place he wanted to be. With her.

“Sooner or later we’d have gotten married.” Lee says, “and I wanted my marriage to be better than what I saw at home. I probably wanted too much. I’m beginning to realize that everything isn’t perfect—you’ve got to give and take. But when it’s been very bad at the beginning, you want everything.”

No, his childhood did not fill him with impatience for the day he would marry. In Ontario, Canada, John Atherly Patterson was a struggling bank teller embittered by the backbreaking burden of supporting his wife and four sons on meager earnings. Lee, born Beverly Frank Atherly Patterson, was the second oldest, the most sensitive and most rebellious of the four boys.

He was also the one stricken with polio as a small child. He had to learn to walk all over again before he could start school, well after his sixth birthday. When he did so, the children taunted him for his patched trousers. The teacher rapped him with the ruler because he wrote the way his mother had taught him at home, while he was invalided.

Through the growing years. up into high school, Lee felt he was always being unjustly picked on for punishment. When he struck back it was worse—he got into trouble with his father. When his mother defended him, the battles raged.

He can still hear the tortured words from his own dry mouth.

“You leave my mother alone . . . you can’t talk like that to my mother!”

The skinny boy, throat aching with held-back tears, would fly at his father, fists swinging. His father would angrily fling him aside, and Lee would drop back whimpering. His mother would scream at his father to leave him alone, and the bedlam became horror.

Home became unbearable

Lee ran errands and made deliveries for drug stores and grocery stores, in the chill of a Canadian winter, he held bottles in freezing fingers. Sometimes he slipped on the ice, and the bottles shattered as he fell.

“You’ll have to pay for them out of your own earnings,” his father told him. “Maybe next time you’ll be more careful.”

Now Lee says his father just was trying to make a man of him. At the time he couldn’t see it. When he was fifteen, home became unendurable to him. The fights between his parents became one never-ending fight, raging day and night. His own battles worsened. The night his father lunged at him and kicked him—and Lee fought back with his fists—was the end. He left and never went back.

His father is sixty-nine now, a traveling man. Every few years their paths cross. There is an overlap of forgiveness, now. The father thinks adversity made a man of his boy. In a way, Lee agrees.

“I say now he was right, bless his heart,” Lee philosophizes with a tired smile. “Indeed it did prepare me. I had a dollar eighty or two thirty or some ridiculous sum in my pocket when I ran away from home, and it lasted two days. I had only the clothes on my back—a sports jacket, a pair of flannel pants, a shirt. My family didn’t know I was leaving—I just disappeared. I traveled around, worked at many jobs, and hitched thousands of miles. I could just about eat and try to stay alive.”

He washed cars, worked on barges, hired out as waiter, bartender, caddy, busboy; worked in jungle surveys, in mines, in lumber mills, criss-crossing Canada until he was nineteen. An inborn artistic talent found expression when he got a job in Toronto, building papier-maché floats for a Santa Claus Parade. In time he was commissioned to design the famed Montreal Santa Claus Parade.

He began to do sculpture and portraits, and enrolled hopefully in the Ontario College of Art. He became interested in designing, and went to Paris to study. But he thought the profession overrun with dilettantes and sub-masculine types. After three days he crossed the channel to England.

“In England,” he relates, “I worked at many different jobs again—as an usher, a trucker, and as boss of a roofing gang made up of Polish D.P.’s (displaced persons) who were tearing down old army camps outside London. There were some rough times on that—fights, knifings.”

His revived interest in designing led to a menial job at the British Broadcasting Company. One day he had to pick up a BBC performer’s check at an agent’s office. He had to walk all the way, he had no bus fare. The agent took one look at Lee and asked if he was an actor. Lee took one gulp, and ad libbed his first myth. He said that he was.

The very next day he was on his way to audition for the part of Happy in “Death of a Salesman.” No richer than the day before, he sneaked on the train to get to downtown London. He brazened his way through readings, landed the part, and was launched on his career.

Before Hollywood tapped him for “SurfSide Six,” Lee performed in twenty-eight pictures up and down the continent. He made movies—and lived it up—in Spain, Italy, France, Switzerland, Germany, Denmark and England. He loved and frolicked in Cannes, Biarritz, London, Paris.

It took six weeks of hassling before Lee signed a seven-year Warner pact, paving the way for his co-starring role in “SurfSide Six.” Negotiator William Orr asked Lee why he was being so hard-headed.

“Because,” Lee answered, “when I put my signature on this contract, I’m going to honor it.”

Not only does Lee like it at Warners, he likes it so well in the United States that he intends to sign a longer term contract—as an American citizen.

The hand that feeds me

“I couldn’t be more American than I am,” he reasons with a chuckle. “I’m so pro-American that I’ll attack my American friends if they criticize the country. I’ve just built a home here. This is the hand that feeds me. And once I’m a citizen I’ll have the right to comment. I don’t feel that I have, now.”

Despite that disclaimer, there are some observations that Lee Patterson just can’t hold back—about himself and the country of his adoption.

“Do you know how wonderful it is to live here?” he exclaims. “To be able to go twenty-four hours a day and get cigarets because everybody has that kind of money in his pocket! You get the slightest feeling you’re thirsty, and you can turn on the tap and get a glass of water. There are countries in Europe where you have to buy water. I’ve seen people go thirsty all day because they’re allowed one glass of water. They can’t afford any more. When you see this kind of stuff, boy, you gotta know you’re lucky.”

Lee feels that he’s often known “the wrong end of the stick,” but that he’s matured without wearing it as a chip on his shoulder. For all his roller-coaster moods, he feels that adversity has enriched, rather than enraged him.

“I could have gone two ways,” he nods soberly. “Sure, I could have been bitter, but that would have meant shutting my eyes to everything good that’s happened to me.”

Meanwhile the myths multiply, and the legend grows. You have only begun to hear about Lee Patterson.

THE END

—BY ALLAN TROTTER

Lee Patterson is seen in “SurfSide 6” on ABC-TV, Mondays at 9:30 P.M. EDT.

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE OCTOBER 1961

Caviggia

11 Ağustos 2023I really like and appreciate your blog. Keep writing.