Marilyn Monroe’s Dream Is Coming True

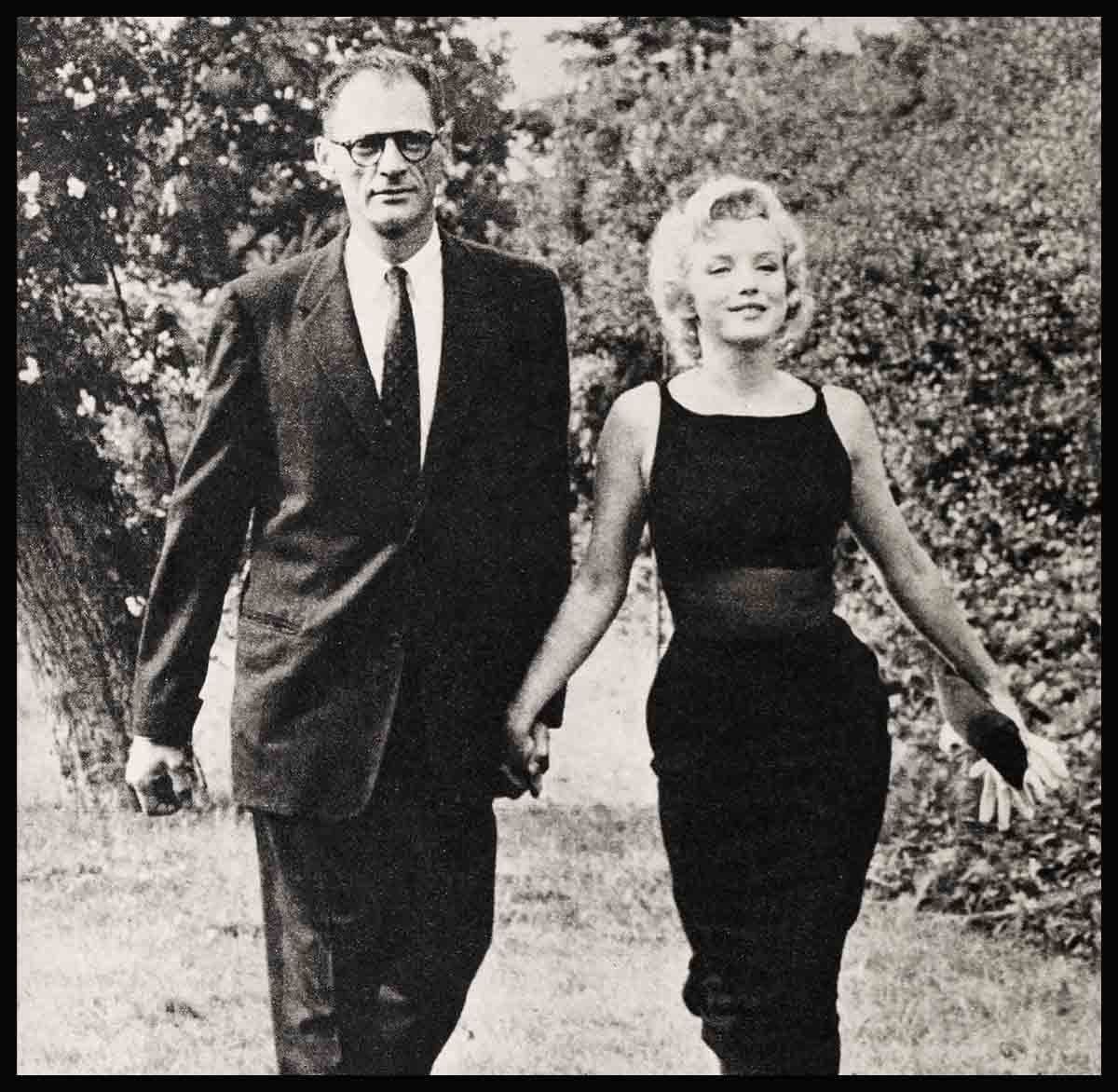

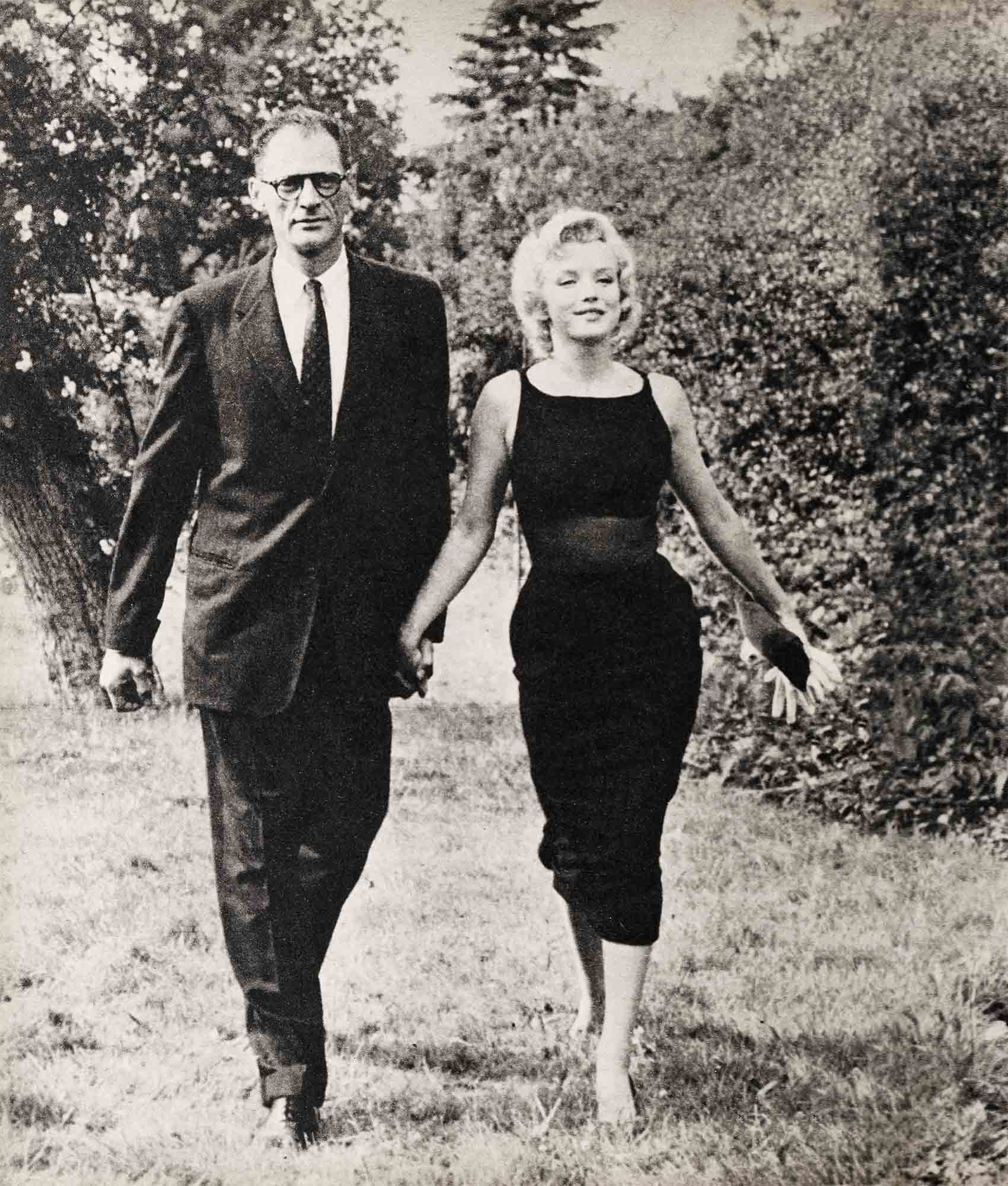

The receptionist in the obstetrician’s office was all excited. Marilyn Monroe, looking very intense, had come in a little while earlier with her tall, serious-faced husband, Arthur Miller, and intense-looking wives didn’t usually come here with their serious-faced husbands unless they thought that maybe they were going to have a baby.

For the next half hour or so, the receptionist kept taking calls and telling people to have a seat, please; the doctor’s busy right now, very busy. While her eyes stayed glued to the door through which Marilyn and her playwright-husband would soon come out, she knew the news would be good news and could see it now—the big smile on Marilyn’s face, the grin on Mr. Miller’s face, the way Marilyn would come over to her and excitedly say, “I have an appointment with the doctor two weeks from today. . . . Would you please be sure to put that down in your book?”

The receptionist was very surprised when the door finally did open. She saw Mr. Miller first. He wasn’t grinning. Not that he looked sad, or anything—but he sure wasn’t grinning. And the receptionist saw why when Marilyn came out. Marilyn was crying. You could see the tears streaming down her cheeks and you could see that her lips were trembling, trembling hard. Mr. Miller put his arm around Marilyn’s waist and whispered something to her as they walked out of the office.

A few minutes later, a nurse walked out of the doctor’s office. The receptionist called her over. “No baby, huh?” she whispered.

The nurse nodded. “Sure she’s going to have a baby.”

The receptionist looked stunned. “But she was crying!”

“I guess some people,” said the nurse smiling, “really do cry when they’re happy. And I don’t think I’ve ever seen happier tears in my whole life.”

The nurse was right. Marilyn couldn’t have been happier than when the New York obstetrician told her she was pregnant. And according to some of her close friends, she was continually in and out of tears for the next three days. “But it’s bad for the baby,” her husband told her the next night when they were sitting at dinner with a few pals and Marilyn, just like that, began crying into her soup.

“The baby will understand,” Marilyn said, putting down her spoon and burying her pretty face in a napkin. “The baby knows why I’m crying.”

Later that night, Marilyn—normally a listener during these after-dinner conversation hours—chatted away. With Arthur sitting beside her, gently rubbing the back of her hand with his warm palm, she talked about the baby she’d just learned she was going to have, about how she and Arthur were going to do everything possible to make the baby healthy and happy. And as she talked, you couldn’t help thinking back to the loveless misery and hurt of her own childhood and you couldn’t help knowing the fight in this girl’s heart to guarantee that her still-unborn child would never, never be touched by any of that misery or hurt.

“My little girl,” says Marilyn—she’s sure she’s going to have a girl—“is always going to be told how pretty she is. When I was small, all the dozens and dozens of people I lived with—none of them ever used the word pretty to me. I used to have this very special dream. I used to dream that Clark Gable was my father and that he had five daughters and I was one of them and that when he came home from work at night he used to come running over to me—not any of the others, but me —and pick me up high and say, ‘Norma Jean, you are so pretty . . . you are so pretty!’ I used to wake up in the morning smiling, for a little while at least.

“It want my little girl to smile all the time. All little girls should be told how pretty they are and I’m going to tell mine, over and over again.”

The horrible childhood

God, too, is going to be made very special and important to their baby. When Arthur was a boy, his Jewish upbringing taught him that God was love and God was good and He was the best friend anybody could have, along with mama and papa. But Marilyn’s mother was away in a mental sanitarium and her father had never been her legal father. And, anyway, he was just plain away. So Marilyn was shipped off to live with a minister and his wife.

Here are the horrible childhood introductions Marilyn had to religion:

“When I lived with the minister and his wife,” Marilyn says, “they told me that if I went to a movie on a Sunday, God would strike me dead. The first time I dared to sneak away and go to a Sunday movie, I was scared stiff to come out. When I did, it was raining. There was thunder and lightning and I ran all the way home, expecting to be struck dead any minute. Even after I was home and in bed, with my head buried underneath the covers, I was terrified. I don’t think it’s right to use God to frighten a child like that. I’ve learned in all the years that have passed that God is everything that is wonderful in this life—and that’s something my baby is going to know from the minute she can begin to understand things.”

It’s no secret to anyone who knows Marilyn well that she’s been waiting for this baby of hers for a long time. “After all,” a friend of hers says, “she’s thirty now and Arthur is her third husband and you might think that if she’d wanted a child badly she’d have had one a long time ago. But there’s some kind of big justice in life—and looking back, it seems only just to Marilyn and her two former husbands that there was no baby then; equally right to Marilyn and Arthur that a child is now on its way.”

When Marilyn was just a kid of sixteen and married to twenty-one-year-old Jim Dougherty in Los Angeles, she knew two things. One was that, like most new brides, she wanted a baby; the other was that she wasn’t in love with her husband. Sure, Jim was a nice guy and all that. But a girl’s guardians can’t come up to her one day and say we’re leaving town soon and we’d rather you didn’t come with us and we’d like you to meet a fellow we happen to know and we suggest that after you meet him you marry him pronto—and expect that girl to be really in love with this all-of-a-sudden husband.

Well, that’s what happened with Marilyn and Jim and, despite Marilyn’s desire for motherhood she and that too-young husband were lucky: they didn’t have a child. After a year of bickering and unhappiness, Jim joined the Merchant Marines, and that marriage was that.

A more complex marriage

Marilyn’s life with Joe DiMaggio was a lot more complex. The wedding took place in 1954, some eleven years after Jim Dougherty had walked out on her. In those eleven years, Marilyn had become the most famous face and figure in the world, a pin-up girl, a Hollywood star. There was nothing now that she couldn’t have. And she decided, after a couple of years of courtship, that she wanted Joe.

On the surface, it was all very glamorous and exciting. Marilyn had just rebelled against her studio for the first time, refusing to make Pink Tights. Joe told Marilyn to pack her bags and come to San Francisco with him. He asked her to marry him.

Yes, all very glamorous and exciting on the surface. But deep in her heart, Marilyn knew that as far as she was concerned, she was simply marrying the man she thought she was in love with, the man who would be her perfect husband and the perfect father of her children.

“And how she wanted children with Joe!” a very good friend of hers will tell you. “Of course, she was attracted to Joe for lots of the obvious physical reasons—big man, Yankee Stadium muscles, soft pleasant voice. But she was also attracted to the fact that he came from a large, happy Italian family, and to the idea that some day she, too, would have a flock of bambinos all over the place.

“Maybe someday . . .”

“She was so happy in the beginning,” her friend continued. “I was with them in San Francisco once and she and Joe invited me over to dinner at his family’s one night. As soon as we got there Marilyn made a bee-line for the kitchen to watch the DiMaggio women go to town with all the antipastos and the spaghetti and what-have-you. They were a quiet family and most of the time Marilyn just stood there watching, sort of not daring to ask any questions. At one point that night, I remember, one of the women started pouring raisins into the meat she was preparing for meatballs and then she sprinkled something else, a kind of white powder, over the meat and Marilyn whispered to me, ‘I wonder what that is?’ I said to her, ‘Why don’t you go over and ask?’ And she said, still whispering, ‘No, I don’t think they want to be bothered now.’ . . . But they were a very nice family and Marilyn liked them an awful lot and she liked it especially when it came time to sit down at the tremendous table they had in the dining room, and you could just see those beautiful blue eyes of hers looking from behind her forkful of veal scallopine and counting all the heads that made up the family and thinking, ‘Maybe Someday. . . .’ ”

That same friend remembers another night, a little more than a year later—a night that was not so pleasant. This time the place was New York, up in Marilyn’s and Joe’s fancy Sutton Place apartment. And this time a GRAUMAN’S THEATRE klieg light couldn’t help you find any feeling of family love around the place.

How pretty she is

Just like Clark Gable used to do in her dreams, Arthur comes out of his Judy and hugs his wife, hugs her hard, tells her how pretty she is. Then he weeps her up off her feet, carries her wards the kitchen and tells her, “I’m going to throw you into one of those pots if you’re not making something I like.”

Then his face lights up into the kind of smile you rarely see in newspaper photos of him as he asks if it’s gefulte fish or chicken soup or other favorites of his.

And Marilyn won’t answer him until he kisses her—and then she’ll say, very softly, “Just for you.”

At least once a week, Arthur’s mother and father drive over from Brooklyn for dinner with Arthur and another new daughter-in-law. And on that night, unlike those nights a few years ago when Marilyn used to stand back in a corner of that kitchen in San Francisco and watch the DiMaggio women prepare the big family meal, Marilyn prepares the meals from beginning to end with Mrs. Miller—who gave her a few lessons in cooking Arthur’s favorites—allowed to do nothing more than help set the table and then sit back and enjoy herself.

After dinner, Arthur and his father—and brother Kermit, if he happens to be along—usually sit in the study and play some cards while Marilyn and Arthur’s mother and sometimes Arthur’s attractive sister Joan, sit in a corner of the living room sipping tea and talking about their favorite subjects—Arthur and the expected baby.

“I think it’ll be a girl”

“Now I must tell you,” the elder Mrs. Miller will say, “that in a Jewish family, before the birth of the baby, there must be no infant’s furniture or clothes brought into the house because it’s a bad luck sign. So no furniture or clothes for the baby.”

“No anything for the baby,” Marilyn will echo, nodding.

“And of course you know that the baby is named only after a relative who is dead,” Mrs. Miller continues. “Of course, it doesn’t have to be the complete name if you don’t want it. Just the initial will do.”

“Just the initial,” Marilyn repeats.

“And if it’s a boy. . . .” Mrs. Miller may start to say.

“But I think it’s going to be a girl,” Marilyn will interrupt.

“Never mind you think a girl,” Mrs. Miller will interrupt right back. “Now if it’s a boy we must get ready to have the bris eight days after the birth, and get the cake, and the wine to drink to you and Arthur and the baby. It’s all very nice.”

And all very nice it is for Marilyn right now, these few hours every week, sitting there with her down-to-earth mother-in-law, feeling good and important and happy with family love in a way that no mere movie star, no matter how beautiful or famous or rich, can just pick up a script and feel.

In fact, those mid-week visits by the Millers are as much fun as the weekly Sunday visits with Arthur’s two children by his first marriage, Joan Ellen, thirteen, and Robert, nine.

Squeals with joy

Every Sunday. morning at nine on the dot, Arthur drives out to Brooklyn to pick up his two children. He goes inside the house for a few minutes, says hello to his ex-wife, and then he and Joan Ellen and Robert all pile into the car and are back at the apartment by about eleven. A friend of the Millers, a photographer, who spent a week end with them recently, described the arrival: “Joan and Robert rushed up to Marilyn and gave her a big squeeze and kiss and then Robert asked if it was time to eat yet. Marilyn kidded him, saying she’d forgotten to do any shopping for the week end and asked Robert if maybe he’d like to walk up the street a few corners and get them all some hot dogs. Robert, a very polite boy, gulped and said sure he’d go. Then Marilyn laughed and took him into the kitchen and showed him the roast beef and baked potatoes she’d made and the ice cream cake she’d ordered and you should have heard that boy squeal with joy.

“After lunch, my wife and I hung around the apartment while Marilyn and Arthur bundled up the kids and took them up to Central Park for a walk and a visit to the zoo. They were gone a couple of hours and it was great to see the four of them walk in together, all holding hands and laughing and trying to outdo one another in imitating a sad-faced giraffe they’d obviously spent most of their time looking at.

“By this time it was time to eat again and Marilyn set up all kinds of luscious cold cuts and potato salad and cole slaw and ginger ale. We all sat around the living room eating buffet style and this was the part of the day devoted to serious conversation—Arthur sitting with Robert having a long talk about how the boy was doing in school, Marilyn sitting with Joan and talking about a few new friends the girl had made and, as I recall, about a very important dress Joan had just bought for a very important party the following Saturday night.

“After supper, we all relaxed for a few hours watching television—Arthur still sitting next to Robert, Marilyn sitting and holding hands with Joan. And then at nine o’clock it was time to go. The good-byes were very excited, filled with lots of exclamations of this and that and lots of laughter. I remember too that they took about half an hour to get over with.

“Then the door closed. Arthur had left to take the children back home. Marilyn was crying. My wife and I have known her long enough to know that she always cries when she’s very happy.

“We’ve known her long enough, too, to know that she’s going to make—you should pardon the expression—a damn wonderful mother!”

THE END

—BY ED DEBLASIO

Marilyn will soon be seen in an L.O-P. Limited Production The Prince And The Showgirl for Warner Bros.

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE MAY 1957