The Truth About Frankie’s Gang

The summer dusk lay soft over the city of Hoboken. Supper was over and from the few tall apartment buildings and the many red-brick row houses, the kids drifted out to enjoy twilight hour.

The boys, proud of their voluntarily washed ears and slicked-down hair, whistled to their friends for a game of stick ball. The girls, having dishes to do and pin curls to comb out, were slower. It was almost dark when they arrived, wearing their fresh cotton dresses and all the lipstick their mothers would allow.

As darkness deepened, they clustered on their favorite steps. A slender lad had a uke; others played kazoos. All of them had the urge to sing. “Always” followed “Let Me Call You Sweetheart,” and “Remember” was paired with “Stardust.” On and on they sang, bewitched by the night and their own music.

Parents, too, came out to hear them, for in this neighborhood everyone loved music and in this group there were at least four remarkably good voices (later professional) to weave the thread of melody. But for one particular listener, all charm was lost. From an upper window came a roar, “Shut up, you kids!” and down plunged a pailful of cold water. Mr. Dunn, who worked the midnight shift t the local firehouse, had his own way of getting those three more hours of sleep to which he felt entitled.

The showers may have dampened their clothes, but never their spirits. Now, more than twenty-five years later, one of the crowd says, “Nothing could stop us singing. We’d just run across the street and start all over again. But I’ve often thought, wouldn’t Mr. Dunn have been surprised if he could have known that one of the kids he doused would become famous— Frank Sinatra.”

“No more surprised than he would have been if he could see some of those stories people now write about Frank when he was a kid,” retorts another member. “So we waked up a fireman—and it later comes out that he was always fighting the cops. The only trouble I remember—if you can call it trouble—was the time we turned on the fire hydrant and ran through the water in our bathing suits. The cop on our beat found our clothes and took them to the station house. We had to go after them, and boy, did we get it from our folks!”

Not too long ago, a retired policeman came to Mrs. Martin Sinatra and said, “Where do they get this stuff about Frankie? That little fellow of yours never gave us any trouble. All of us liked him—what little we saw of him.”

The men and women who knew young Frank Sinatra strongly resent the many stories, appearing in even some of the most respected magazines, which picture Frank as an apprentice hoodlum. Remembering him as “a scrawny lad with a wide grin and a heart as big as himself,” they wonder if some writers aren’t getting Frank’s boyhood mixed up with the plot of “On the Waterfront,” filmed in Hoboken.

Hoboken, they will admit, has garnered its share of headlines. It is a mile-square city just across the Hudson from lower Manhattan, and ships from all parts of the world anchor there. However, Frank Sinatra’s friends would like people to know that any violence which broke out on the docks never touched him.

“Frankie a fighter?” says Terry Bartletta Carmody, now the wife of Hoboken’s city administrator. “The only time I ever saw Frankie fight was when he caught a couple of boys tormenting a dog.”

“He never needed to fight,” says Terry’s sister, Lee Bartletta Amorino, who until recently combined a career as a legal secretary with her full-time job as a wife and mother. “Everyone liked him and the Sinatra house was a second home to all of us. And manners—that boy was loaded.”

Because Mrs. Amorino treasures these memories, she decided to do something about the many erroneous reports. She wrote a letter to Photoplay citing facts of Frank’s childhood. “I know,” she wrote. “This was part of my life, too.”

Thanks to the help she gave, this reporter was also able to talk to a few of the other old friends—Mrs. Carmody, Tony Maccagnano, now the owner of a dairy, Daniel Hannagan and his wife, Agnes, both employees of Hoboken firms, and finally to the woman who should best know what actually happened during those formative years, Frank’s mother.

With a mother’s loving patience, Mrs. Sinatra explained why—even when they have all been hurt by false statements—they have never lashed back at those who published them. “I’ll admit I was terribly upset by one particular article which ran in a magazine which is supposed to be accurate,” she said. “When Frank phoned me that week, I said, ‘Frankie, this time I’m going to write a letter.’ Well, Frank reminded me, ‘Mama, you know the time I got so mad at a guy I was going to tell him off?’ ”

Dolly Sinatra well remembered. She had calmed that particular case of teen-age sputters by suggesting Frank take a tip from a politician they both knew. “When someone prints lies about that man,” she advised, “he never issues a contradiction. That would be just what the opposition wants him to do. That would keep the fire going. So he waits for a chance to let people find out something good about him instead. You try it too, Frankie. You’ll find out silence is golden.”

Frank never forgot. Now, when it was her turn to sputter, he replied, “Remember how you told me silence is golden? Mama, please take your own advice.”

Mrs. Sinatra heeded and never wrote the letter, but when Frank’s old crowd chose to tell Photoplay the true story, she arose from a sickbed to verify facts and add those vivid details which only a mother can recall. “The stories about Frankie running with a tough gang concern our friends, too,” she said. “They don’t want their children to believe them. They were

all such wonderful kids and they’ve grown up to be such fine men and women.”

Frank, too, cherishes their friendship. “The first thing he does when he comes home,” she said, “is to ask about them. Not just the men and women you met, but all the others—Billy and Marie Roemer, the Schreiber boys, Billy Bradley, Hilma Paulsen, and many more.”

One of the most effective ways these long-time friends have of setting the record straight is to conduct a tour of the old neighborhood. The Carmodys, the Hannagans, Tony Maccagnano and a number of the others still live there. Many of the people who grew up in the area have remodeled the substantial old houses to suit today’s convenience. It’s still home to them.

Lee Amorino, who was this reporter’s guide, now lives in near-by Ridgefield, New Jersey, but returns often to visit family and friends.

She pointed out her house and those the Sinatras had, a few blocks farther on. “The higher you went in the numbered blocks, in our day, you were just a teeny bit ritzier. None of us had money to burn, but we weren’t poor, either. We were just middle-class people living ordinary lives.”

The center of the community is Church Square, a pleasant park where slides and swings surround a bandstand. Along one side of the square is the beautiful St. Mary’s Roman Catholic Church, together with its hospital, its schools, its orphanage and the residences of the priests and nuns. On the opposite side is Demarest High School which Frankie attended. On the side nearest their homes is a library, a vocational school and a private school. Leading from it are the streets where the Sinatras lived. They were first at 705 Park, then bought the eight-room redbrick row house at 841 Garden.

Both Martin and Dolly came from large, happy Italian families. Martin was the handsome, husky young man who achieved some local recognition as a boxer, tended bar a bit, then joined the Hoboken fire department. When he retired last spring, he had attained the rank of captain.

Dolly, tiny, pretty, bright-eyed and volatile, became a practical nurse. “My mother took care of Frankie whenever I was working. That boy was never alone,” she says.

It was her love of people, however, which opened up a new career for Dolly. “When Women’s Rights came in and we got the vote, Mayor Griffin sent for me. Because I knew everyone and spoke practically every Italian dialect there is, he asked me to become the leader of the Ninth District. It’s one of the largest districts in the city.”

Energetic Dolly has reason to remember every step of it. She covered her district so thoroughly she was credited with swinging it from Republican to Democratic.

The next mayor, Bernard N. McFeeley, had an additional task for her. The official title was that of interpreter to the municipal court. Speaking of it, Dolly now says, “Actual interpreting took very little of my time. Sometimes, when I had appeared in court only twice in a week, I’d tell the mayor I felt ashamed to accept my check. Then he’d remind me of all the other things I was called on to do.”

The “other things”—all unofficial, but important—might be described as being social worker, welfare agent, parole officer, family relations counselor and little mother to the community. Whenever there was trouble in a family—hunger, sickness, minor infractions of the law—Dolly, being unofficial, could often win a confidence and find a solution faster than the “authorities.” She knew how to counsel, comfort, rebuke or find help. There were no office hours for this sort of task. Her phone could ring at midnight, a frightened woman might knock at her door at four a.m., or a teenager might just drop in for a bit of advice. Many of her dollars went to tide over someone in need. Some magazines have dismissed all this by saying, “Mrs. Sinatra was in politics.” Her younger neighbors affectionately offer a more intimate view.

“In the Thirties,” Agnes Hannagan remembers, “after we finished high school, there were no jobs to be had, but the mother of one of the girls pushed her out of the house every morning at eight o’clock to look for work. She’d stop to get me, and then, because neither of us knew what to do, we’d go see Mrs. Sinatra. She’d give us a cup of coffee and cheer us up. Sometimes she’d know of some temporary job where we might earn a little money. We could always count on Mrs. Sinatra.”

“The Sinatras were always open-handed and hospitable,” says Lee Amorino. “We knew that any time we asked, Dolly would let us gather in their home for an evening.”

All of the old friends speak of those evenings, and especially the two extra added attractions—Frank’s radio and Pops’ cooking.

“Pops” was Martin Sinatra’s father who had come to live with Martin and Dolly after his wife died. “With both of Frankie’s parents going to business,” Lee Amorino remembers, “his grandfather was the one who kept an eye on him, and on us, too, for that matter. He was a fine, gentle old man. He and Frankie were very close.”

“Not just Frankie,” Mrs. Sinatra says, “but all the children in the crowd became Pops’ whole life. When they were coming in for an evening, I’d get cold cuts, cake and cream soda, but that wasn’t enough to suit Pops. He’d always cook up a batch of spaghetti—and could those kids eat it!”

“He was our chaperone and a more lovable one you couldn’t want,” says Lee. “We’d sit around and listen to the radio. Rudy Vallee, Russ Columbo and Bing Crosby were our idols. And we’d dance—the Charleston, the Black Bottom, the Lindy Hop. Frankie’s radio was something special. It looked like a small grand piano.”

One of their parties still brings chuckles to members of the old crowd. The Hannagans speak of it as “the time the girls got locked in the bathroom.”

One of the boys thought it quite a prank, Agnes explains. “My sister Margaret and Hilma Paulsen got into one of those long, girlish gossip sessions, so somebody sneaked up, locked the door and hid the key.”

When the girls found out they er trapped, so much commotion ensued, culprit lacked the nerve to confess and open the door. Two hours later, the girls were still shouting. Tony Maccagnano says, “It was Frankie’s particular pal, Billy Roemer, who figured out what to do. He always was mechanical. So he pulled the pins out of the hinges and he and Frankie lifted the door right out.”

Frankie and Billy maintained a workshop which was the envy of all the other kids. “Lindbergh’s flight had made us aviation bugs,” says Tony. “Frankie and Billy built the best model planes of all of us. They were always winning first prize in contests the merchants put on.”

Such a prize brought Frank his first plane ride. “He came in all excited,” Dolly Sinatra recalls, “and said, “You be sure to look up, Mama. Ill wave to you.” And, do you know, I was just as ignorant about flying as he was. I went outdoors and craned my neck, expecting I’d be able to see him. It was about that time that we began planning for Frank to go to college and become an aviation engineer.”

While their early teens had been carefree, the Thirties drew the kids even closer together. The deepening Depression put bald spots on many a family’s budget, and the kids often pooled their wealth. “After a stick ball game,” Dan Hannagan remembers, “we’d pitch in whatever money we had to buy three-penny lemon ice. It was the same with movies. No one was ever left out just because he didn’t have the price of admission.”

“I get a funny feeling, now,” says Agnes, “when we go to one of our theatres and see Frankie up there on the screen. I remember how many times he sat in those same seats beside us.”

Frankie had a bit more money than some of the rest of the kids and was always generous. Agnes cites an instance when that generosity took an unexpected turn. “One of the boys had been having a pretty rough time, but he finally earned a little money and Frankie decided it was time he had some better clothes.”

Frankie and friend repaired to Geismar’s, a men’s shop where, even then, young Mr. Sinatra had a charge account. His credit would supplement the other lad’s cash. Frank wanted the boy to look real sharp.

“It’s the only time I’ve known Frankie to go wrong about clothes,” says Agnes. “Trousers with checkerboard waistbands were the rage. Frankie could have worn them, but not this other fellow. Frankie also insisted he get some pointed shoes.”

Dan takes up the story: “I’ll never forget seeing those two come down the street. By the time they reached Sixth and Washington, those pinching shoes had become unbearable. So there was Frankie, looking miserable and embarrassed, and our other friend, in those silly checkerboard pants, was limping along, carrying his shiny new shoes. You never saw two sadder guys!”

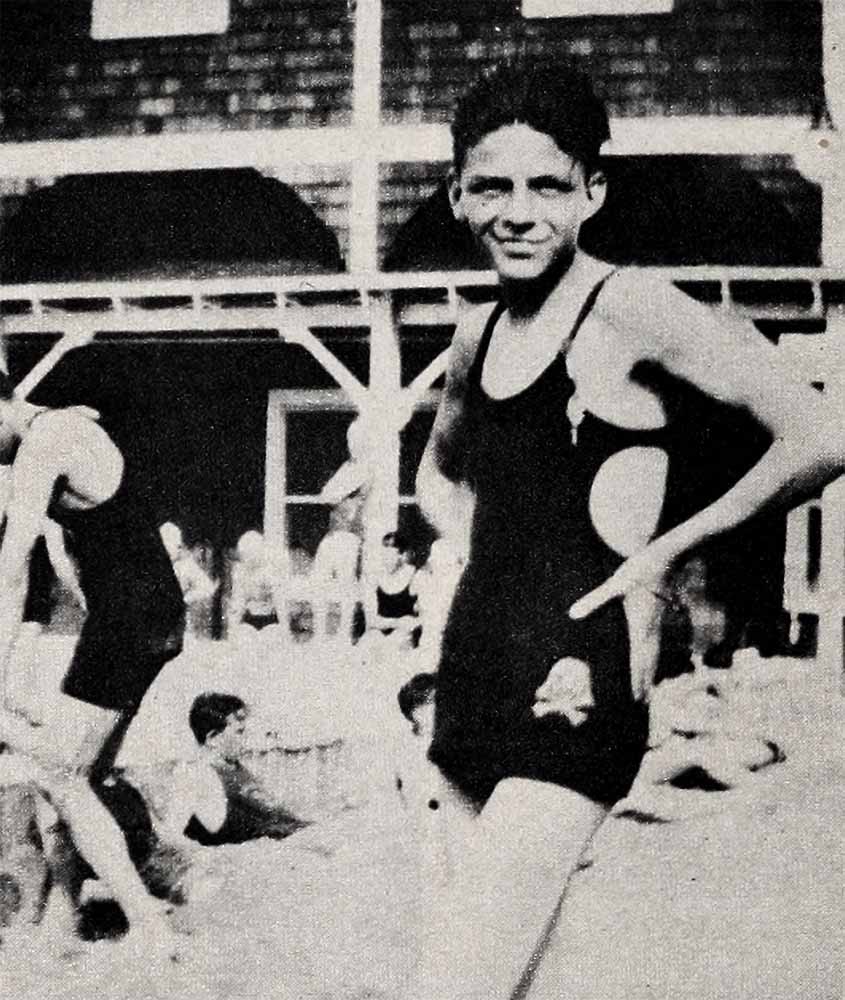

Mrs. Sinatra was responsible for the most elegant of their outings. All the crowd loved to swim and usually, having the price of admission but lacking carfare, they piled into Schreibers’ truck and went to a neighborhood pool or to Palisades Park. But to a political rally at Rye Beach, they went in style.

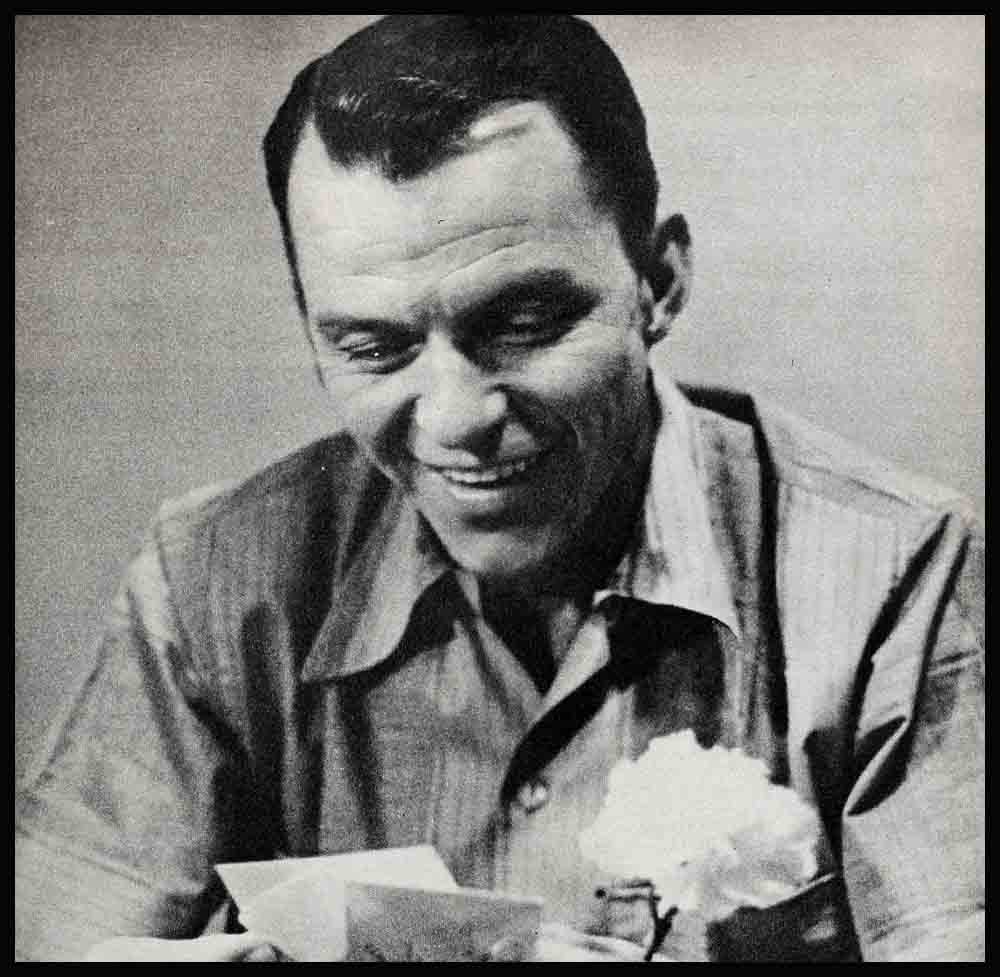

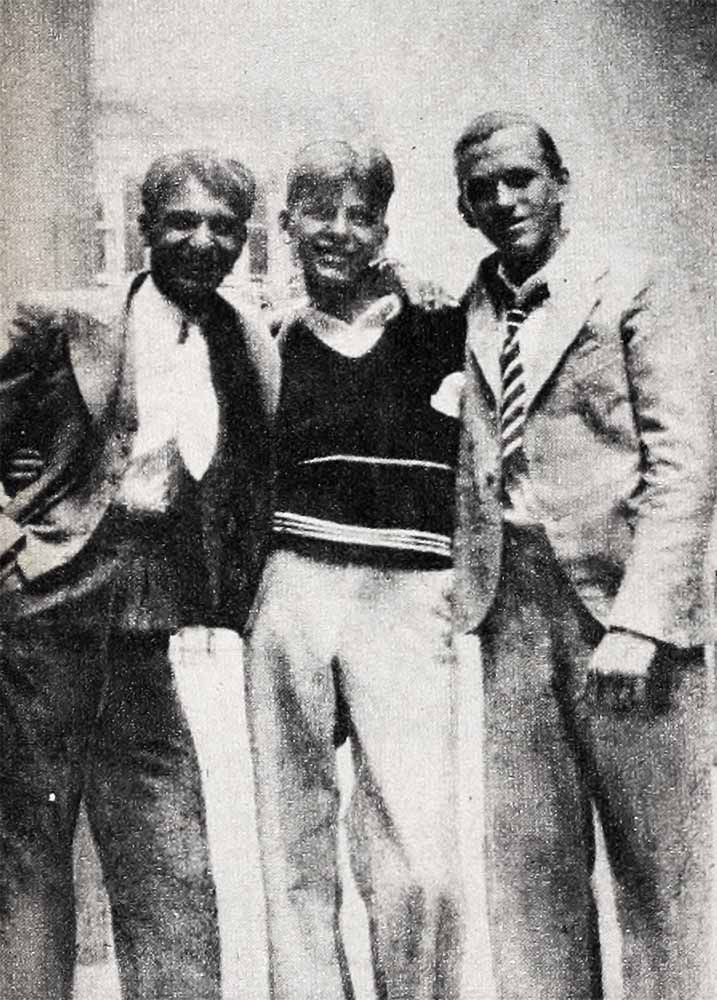

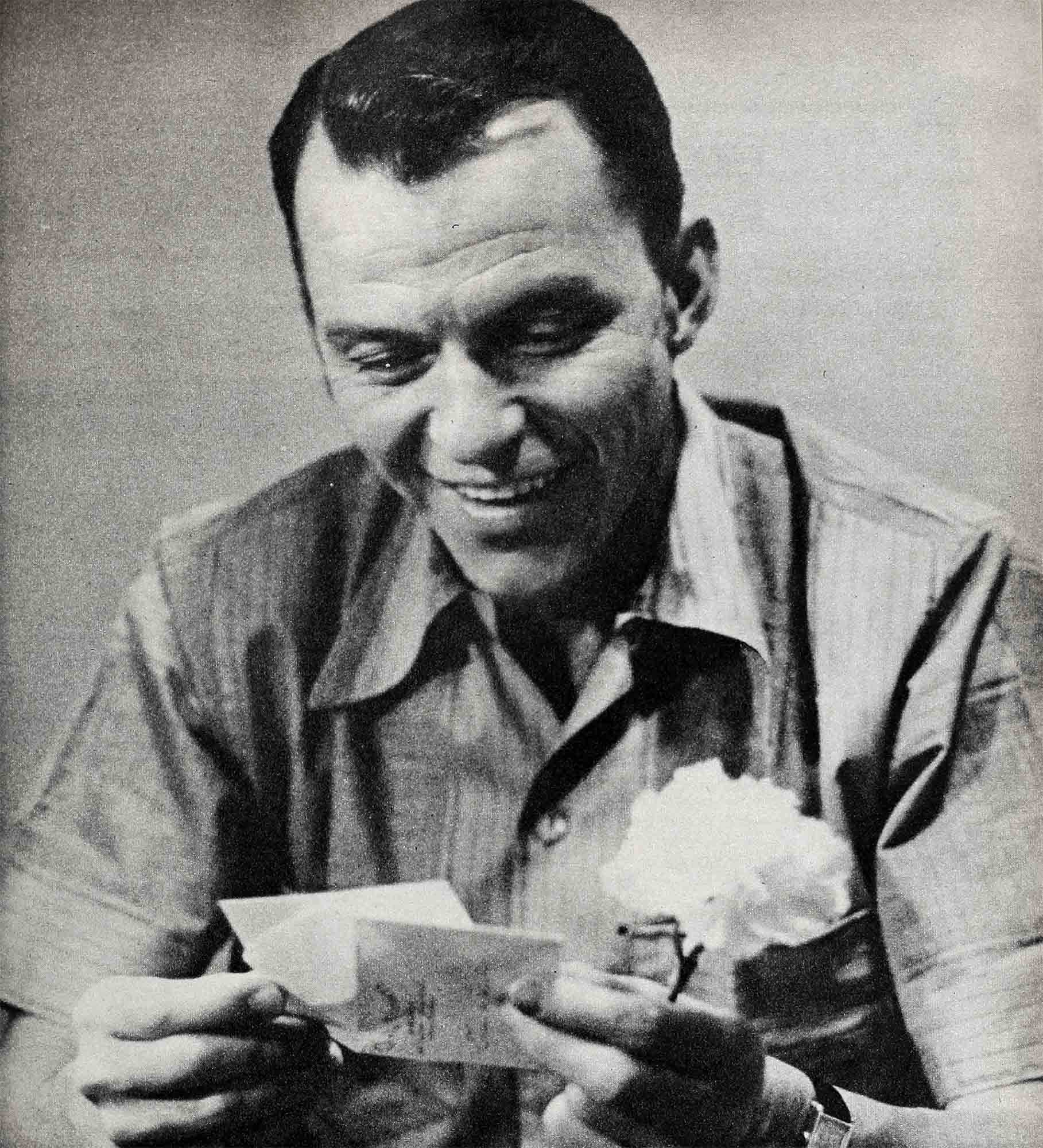

“Mrs. Sinatra had a taxi call for us,” says Agnes, “and she sent a man along to carry the big picnic basket. I suppose he also watched out for us, but we never thought of that. We were too busy being big shots. Although we usually didn’t have the money for films and developing, we did take pictures on that outing.” She has cherished the snapshots all these years; two of them are included at the beginning of this story.

Marie Roemer, pictured on page 54, was Frank’s first girl. Lee Amorino recalls that she was called on to play amateur Dorothy Dix. “I was a bit older and inclined to feel like Frank’s big sister, so he asked me how to win Marie’s attention. I tried to help him out, to the best of my sixteen-year-old knowledge. When we got around Marie to the extent that she accepted a birthstone ring he bought her for St. Valentine’s Day, you’d have thought she had handed Frank the world on a silver platter, just by agreeing to go steady.”

Dates, of course, called for a car, and the crowd’s first automobile was a sensation. “That was a corporation,” laughs Dan Hannagan. “It cost a total of twenty dollars and we all owned shares. Billy Roemer stayed up all one night working on it.”

The paint job, too, was a joint project, and Frank was thrilled beyond words with it. “It’s a dreamboat, Mama,” he reported.

“Dreamboat!” says Mrs. Sinatra today. “It was a nightmare. Every wheel was a different color, it had no top, and there were wisecracks scrawled all over it. When he parked it in front of the door, I made him take it away. I was afraid the neighbors would think I had gone crazy.”

Frankie held the only driver’s license and, one day, with him at the wheel, as many of the kids as could pile in set out for Atlantic City. The motor may have been smooth, but the brakes were smoother. At Elizabeth, New Jersey, a stoplight turned red in Frank’s face and he crashed into the car ahead. No one was hurt, but an SOS was sent to Martin Sinatra.

“Boy, was he mad,” says Tony. “He had that car pushed onto a vacant lot right on that corner where the crack-up happened. He set fire to it and wouldn’t leave until it was all burned up. We sure mourned the work that went into that motor.”

Dan Hannagan, who was employed in the stock room of a New York publisher, was for getting Frank his first job. He spent the summer as a clerk.

That marked the end of Frank’s formal education. The story has been printed that Frank was expelled from Demarest High School for “general devilishness.” This, Dolly Sinatra asserts, is not true. “When fall came, he just refused to go back to school.”

Still cherishing the dream that he would become an aviation engineer, the Sinatras were much troubled. “We talked it over with a professor,” says Mrs. Sinatra, “but to our surprise, he agreed with Frank. He told us that if we insisted on sending Frank to engineering school, we’d be wasting our money, Frank’s time, and the school’s facilities. He pointed out that glee club was all Frank cared about.”

Dolly Sinatra was particularly reluctant to accept the decision. Frank compromised by going to work for The Jersey Observer, first on one of their delivery trucks, then as a sports reporter.

Terry Carmody holds a fond recollection of Frank Sinatra, newspaperman, age approximately seventeen. “I was just enough younger to think Frank was a hero. He had a brown corduroy jacket, a porkpie hat, that bow tie of course, and then he added a pipe. He had no tobacco in it, but it became his favorite prop.”

Interesting as it was, sports reporting could not compete with singing, and Frank soon found that a public-address system his mother had given him provided an open sesame. “It had a mike and speakers and a case covered with some sparkling stuff,” Tony recalls. “Those things were rare in those days, so when Frankie would let a band use his p.a., the leader would usually let him sing—for free, of course.”

Because Tony sometimes joined in those songs, he felt he had a right to be critical when Frank did his first radio program. “I heard him on WAAT and the next time I saw him, I said, ‘You’d better quit. Boy, you were terrible.’ ”

Tony wasn’t the only one who thought so. Dolly Sinatra will never forget the day that Frank came in, anxious and unhappy. “Mama,” he said, “there’s an opening at the Rustic Cabin.”

Dolly, who had her own ideas of what her son’s future should be, replied, “Opening, closing, it’s all the same to me.”

“But the bandleader doesn’t like me.”

“That’s just fine,” said Dolly. “I won’t have you staying out until all hours, singing in one of those night clubs.”

Her objection was the final crusher. “Frankie just looked at me,” she says, “and he didn’t say a word. He took his dog, Girlie, in his arms and he went up to his room. Then I heard him sobbing.”

To have her grown-up, happy-hearted son cry was too much for the devoted Dolly. “I stood it for a couple of hours, and I suppose I realized then, for the first time, what singing really meant to Frankie. So I got on the phone and I called Harry Steeper, who then was president of the New Jersey musicians and now is James Petrillo’s assistant. I said, ‘What can we do? Frankie wants to sing at the Rustic Cabin and the bandleader doesn’t like him.’ Well, Harry had heard Frankie sing, and he must have noticed the start of that quality which Frankie later learned to bring out so effectively. So Harry said he’d fix that—that I was to tell Frankie he was as good as hired. That’s how it happened. So many people claim to have started Frankie professionally, but the truth is it was actually Harry Steeper.”

The engagement at the Rustic Cabin brought Frank’s first break with the old crowd. “We would have liked to go hear him every night,” says Dan Hannagan, “but the prices there were too steep.”

Tony has his own reason to recall another memorable day in Frank’s life. “I had a milk route, the truck broke down and I was having a horrible time trying to carry milk bottle crates in a rumble seat. It was just daylight when along the street came Frankie. I asked him what he was doing out so late and he said he had just cut a record with Tommy Dorsey. That must have been his first hit, ‘I’ll Never Smile Again.’ ”

At the same time, they all could have sung, with feeling, “Wedding Bells Are Breaking Up That Old Gang of Mine,” for Frankie had met and fallen in love with Nancy Barbato.

“Everyone,” says Agnes, “expected that Dan and I, who had been going steady all through high school, would be the first to marry, but it turned out to be Frankie.”

Their days of close association were over. Some went on to school, some found jobs, some married. Different interests gave a different direction to their lives.

But they were to learn that Frankie, though famous, was still their friend. In the midst ofthe screaming riot of bobbysoxers who—during his first big engagement at the New York Paramount—overflowed into Times Square, Frankie saw to it that old friends from Hoboken had a clear path through the swooners.

All members of the old crowd have their favorite stories of similar visits through the years. Terry Carmody remembers when she and her husband, Daniel, chose not to do an I-knew-him-when act while at a New York night club. Frankie, however, spied them in the audience and came racing over to their table.

Tony tells a particularly story. A neighbor’s daughter had been ill, and because the youngster adored Frank, Tony thought it would give her a boost toward health if she could see him. Warmhearted Tony went to the trouble of getting a night-club manager’s permission to bring the young girl to see the show. He promised her he would get her Frankie’s autograph. When Frank learned about the little party, he came to the table and sat with her until time for the next performance. “She was so thrilled and excited,” says Tony, “she just trembled.”

Not too long ago, Dan and Agnes Hannagan went over to Manhattan to watch Frankie do a television show. An usher was insisting it was impossible for them to go backstage to say hello when Dolly Sinatra discovered them. “She threw her arms around me,” says Agnes, “told the usher to take us on stage, and we ended up being guests at Frankie’s birthday party.”

Frank’s generosity in appearing at benefits in Hoboken also endears him to his old friends. “If he’s in New York and we have something going on,” says Terry Carmody, “we know that if he can manage it, he will be over.”

The path to fame is always a lonely one and, in Frank Sinatra’s life, it has often been turbulent. Yet through the years, he has continued to earn, and give, both affection and loyalty. Those who have known him the longest still love him the best.

Tony sums it up. “Come to think of it, I know of only one thing Frankie has ever said he would do that he didn’t. Last time I saw him, he noticed I was getting kind of bald on top. So he yelled out, ‘Hey, Tony, when I get back to Hollywood, I’m going to get you a rug—a hairpiece. I’ll put your curly locks right back on your head.’ That’s the only thing I’ve ever known him to forget, but at that, it might be a little inconvenient. How could I get my head to Hollywood for a fitting when I’m kind of busy using it right here in Hoboken?”

The defense for Frank’s youth rests.

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE SEPTEMBER 1956