The Triumphant Years—John and Patti Derek

There are those who say that every marriage is a gamble. The more cynical will go farther, maintaining that every marriage is a gamble with the cards stacked against the two principal players. In Hollywood, particularly, this view is widely held.

John and Patti Derek do not share it. Emphatically, they do not.

A few months from now—in October, to be precise—the Dereks will have been married six years. Their son, Russell, will be almost five, their daughter, Sean Catherine, just one. They will be either just a shade less in debt than they are now—or a great deal more. They will be quite ridiculously content.

Because in not quite six stormy eventful years, they have discovered what many young couples in Hollywood, as in Peoria, Illinois, never do discover—that marriage is not a gamble, nor a game of any kind, but an education. That whether you flunk out or get passing grades is strictly up to you. More, that while flunking out would leave you, oddly enough, less of a person than when you began, passing grades (there is no diploma) enrich you ever more and more.

They are in love, the Dereks. Not in the wild, fabulous, out-of-this-world manner of young lovers who have no thought beyond the immediate date they are sharing. They are not even in love as were, seven years back, John Derek the young film discovery and Patti Behrs the petite young actress with the faint French accent, the saucy figure, the eager, personal ambition.

No, they have advanced from both those giddy moods. They are a couple now. They are parents now. They have gone through the problems that almost every young husband and wife experience, the quarrels, the worries, the fears of childbirth, the agony of a baby’s nearly fatal illness, the money uncertainties. The latter are very much with them still, for in actual cash, the Dereks have practically not a dime.

Liberated from his contract with Columbia Pictures, which gave him his first chance at fame with “Knock On Any Door”—and, after that, gave him little except misery and a regular salary—John is now a freelance actor. Freelancing may mean something very great for him. Or it may mean nothing. Here, if you like, is a gamble. But John and Patti are facing it with courage and serenity, according to their separate natures.

“I’m not afraid of the future,” John tells you almost angrily. “I’m not afraid of it either,” Patti echoes, her voice very gentle. Across their most uncrowded living room, which would be much the better for a few more chairs, tables, and other objects of creature comfort, their glances meet; the male, challenging; the feminine eyes reassuring.

Oh, they’re master and mistress of a big rambling house set on a high knoll overlooking the San Fernando Valley. They have three and a half acres of land and a swimming pool. But half the land is untilled because the only gardener John can afford is one willing to work for $100 a month or less—and few are. He cleans the pool himself to save the $25 monthly a regular pool man would cost him. Patti has no maid, and they do their own babysitting, spending most of their evenings at home alone with the children, watching TV. Their monthly mortgage payments just about break them.

Not having things—material things—can be a strain on any marriage; it can be more of a strain on a Hollywood marriage. Talking to John and Patti, you have the feeling that in their case the importance of money has been assessed and put in its proper place—not at the bottom of the list but nearer there than to the top.

About them both, after more than five years, you still sense the glow, the aware- ness of the really big miracle—that out of all the people in the world each might have met and married, John found Patti and Patti found John.

John was born of two incredible people in the incredible town of Hollywood in the fantastic twenties—August 12, 1926, to be exact—and brought up in a way to make child-guidance experts cringe. His father was a producer. His mother was an actress. From both parents, John inherited astonishing good looks, which have been more of a misfortune than a blessing to him. The world gives lavishly to beautiful girls, but it tends to be stern with extra-handsome boys—as if beauty were something they could help if they’d only try.

John—actually his given name was Derec, Derec Harris—was a very rich and pampered little boy. Sometimes. Sometimes he lived in a great white house on the then-fashionable Sunset Boulevard and had a swimming pool—when pools were very rare—and rode polo ponies and went places in block-long automobiles. Other times, he didn’t have anything.

Sometimes he had a mother and father who lived together and showed him off like a favorite pet. He was supposed to behave perfectly when being shown off, and he did.

His mother loved to walk down Hollywood Boulevard holding two white Russian wolfhounds on the leash. They looked as beautiful and aristocratic as she. Her little son looked beautiful and aristocratic too, and he knew that mother didn’t like it if he cried, or even laughed too loudly. Today Patti says, “If only John could learn to express his emotions more! When I’m angry, I explode. When I’m happy, I literally dance with joy. The night we thought our baby was dying, John was like a statue. I know he was suffering even more terribly than I was because he couldn’t let any of his fear come out.”

With his own lifelong habit of repression, John was first attracted to Patti by her vivacity, her naturalness and charm. And for a romantic nature—which he has—her background had enchantment too, for she was born a Georgian Princess, she had been educated in Paris and she was expected to become a star at 20th Century-Fox, which had imported her.

It’s likely, too, that she charmed John with the oldest trick in the feminine lure book—by being unaware of him. They met in a drama class at 20th Century-Fox and she barely glanced his way. This was a disturbing novelty to John. Ask him now about his frantic popularity with girls in high school and he’ll answer carelessly, “Any guy with a convertible is popular in Hi.” He knows better than that. Girls in school swooned when he went by, just as later, when he’d clicked in “Knock on Any Door,” established glamor girls rolled their mascara’d eyes at him.

All except Patti. Actually, she was annoyed at him. “I was dying to act,” she explains, “and John just didn’t seem to care. I couldn’t understand how anybody could be so indifferent.” Now that she’s his wife, she knows he wasn’t indifferent at all. His attitude was just the protective shell he’d learned to cultivate, in order to hide his real feelings from a world he suspected of being unfriendly.

John at that time wasn’t too long out of the Army, where he’d again had a rugged time on account of his looks and Hollywood background. He was known—vaguely—around Hollywood as a “possibility.” He’d had many screen tests, a couple of minor contracts. His parents had been divorced since he was five. He was a rootless young man whose principal strength was that he honestly believed he needed no one and could feel no emotion so strongly that he couldn’t hide it.

But somehow Patti’s antagonism pierced that shell He began calling her. She gave him one date, then a second and a third. He heard himself confiding to her an ambition he’d hardly dared confess to himself—to play Nick Romano in “Knock on Any Door.”

The spring melted into summer and John Derek knew he was happy as he had never dreamed he could be. One mid-August day he woke up smiling, thinking of the date he had with Patti that evening. He hated dressing up—still does—but he’d promised that just for her he’d go not only as far as to wear a shirt with a collar and tie but even a jacket. That he’d be on time went without saying. He is a bug on the subject of punctuality.

Thus, seven on the dot, he rang the bell at her small apartment. The door swung open and he saw a crowd inside—his friends, Patti’s friends. “Happy Birthday!” they shouted.

His reaction was shocking. White-faced, he backed away, slamming the door, shutting himself out, alone, in the hallway. In an instant, Patti flew out and threw her arms around him, pulling him back inside. He was twenty-two that evening in 1948, and in all his life, this was the first time anyone had ever given him a birthday party.

It’s possible—more than possible—that the process of education which was to continue for John throughout his marriage began then and there. For see what came next:

Not many days afterwards, two things happened to him in quick succession. He was dropped from his contract at 20th Century-Fox—and he landed the role of Nick Romano at Columbia. The day he was signed for it, he rushed to Patti, begging her to elope with him to Tia Juana.

She was too sincerely in love with him to agree. She knew he must keep his whole mind on this great acting opportunity. But she didn’t tell him that. Instead, she invented an excuse—she had to get her passport in order before she could cross the Mexican border.

The climactic scene in “Knock on Any Door”—climactic, that is, for John’s role—required him to break down and cry. On the day that scene was to be shot he was very nearly a nervous wreck. No tears would come. Nick Ray, the director, talked to him. Bogart talked to him, sympathetically. He walked back and forth, while the whole stage waited. He clenched his fists. He felt as though his whole body were aching—and he knew he couldn’t cry.

Then he found himself thinking of Russell Harland, the cameraman who had virtually adopted him after his parents had separated and who had taught him to ride and box and to understand a little about life. He thought how, if he failed in his part, he would be failing Russ who had never once failed him. He would be failing . . . Patti.

The realization overwhelmed him, broke through his proud reserve. He began to cry. But the actor in him remembered his lines, remembered his position before the camera, remembered cues.

He heard applause. He knew the scene was finished and he had scored. He heard Nick Ray praising him. He felt Bogart shaking hands with him. But he went on crying. They were slapping him on the back, they were laughing, sympathetic laughter. He went on crying. He got out to his car, finally, but he was blinded by his tears, he couldn’t drive. It was nearly three hours before he could stop, this young man who had trained from babyhood not to cry.

Who can tell—certainly not John—whether or not he could have measured up to the emotional demands of that scene if it hadn’t been for the birthday party, and Patti, and the release her love gave him? The fact is, he did.

Even before he got home that evening, the news was going around. Word that a star has been born travels faster through Hollywood than a jet plane over it. He drove straight out to Patti’s. They fell into each other’s arms, kissing and laughing and talking all at once. It was some time before John could say, “I can afford a wife now. To go to Las Vegas, you don’t need a passport. Let’s elope tonight.”

He didn’t tell her that days earlier he had bought matching gold wedding rings—but then Patti didn’t tell him that she’d already bought a black, sheer nightie and a just-as-black and twice-as-sheer negligee. They intended to surprise each other.

They didn’t elope to Las Vegas that same night because Hollywood stepped in with the special problems Hollywood has for young love. “Elope?” Columbia Pictures snorted at John. “Well, all right, but not until Saturday night, so the story can make the Sunday edition.”

“Elope?” 20th Century-Fox snarled at Patti. “On Saturday night? Well, okay, but don’t you forget to be back on the set of your picture by eight Monday morning!”

Meekly, they obeyed orders. Today they both wince as they recall their fast, un-romantic wedding at the Las Vegas Hitching Post. They laugh ruefully, remembering how they took the first possible plane back to Hollywood and the little bungalow in Santa Monica Canyon which Patti had rented for them “because it was cheap.” Most deflating of all, in their excitement, John had forgotten to take along the wedding rings and Patti had neglected to pack her nightie and negligee.

But none of that mattered—for they were in love, in the first mad, glorious, exciting, thrilling moment of marriage.

It was sheer heaven. Except . . .

Except that the little bungalow in Santa Monica Canyon was dark and dirty—and John hated thrift of any kind.

Except that Patti, with her French upbringing, was a wonderful cook, and on their first morning together she proudly turned out a breakfast that would have made Escoffier himself smart with envy. How was she to know that John never feats breakfast—“unless it’s a gallon of milk”? Or that he considers any meal great as long as it is steak and sliced tomatoes? Anything else is just show-off.

On that honeymoon, which they spent largely cleaning house, Patti learned that John is supremely unhandy. He is not one of those dependable males who accomplish miracles with a screw driver, a hammer and a saw. He is baffled by a leaking faucet or an uncaulked window or even a burned-out light bulb.

But John also learned that Patti is afraid of horses and would as soon sleep on a bed of hot coals as without a roof over her head. She is not the outdoor type.

It is dangerous to life and limb, Patti found, to waken John too abruptly in the morning, no matter how early his studio call. While John discovered that Patti can see little wrong with being anywhere from fifteen minutes to two hours late for all appointments.

Their extravagances didn’t match, and neither did their notions of thrift. Patti bought a very expensive dog, Annie, thinking cleverly to breed her and sell the puppies at fantastic profits. What happened was that she loved the puppies so much she couldn’t bear to let one go.

On the whole, like any bride, Patti had to learn more than John—for no real man ever does change very definitely, even for the one he loves.

In addition to the normal adjustments all newlyweds must make, there were the special hurdles peculiar to Hollywood marriages. Take the night they hired a limousine to attend the premiere of “All the King’s Men,” John’s first picture after “Knock on Any Door.” He wasn’t too happy about his role in this—it was small and a step down, rather than up, from his spectacular debut. But the picture itself was important, and so was the premiere. John knew their own car was too shabby to use in such swank surroundings. Hence the rented limousine.

Appalled at the cost of the car, Patti nevertheless threw thrift and caution to the winds and bought a lovely new dress. (John had been able to borrow a dinner jacket from the studio, but this wasn’t a service available to her.) She knew she looked exquisite as they set off to the theatre. But when they reached it and stepped out, the crowd swirled around John. He was borne off and away before he could rescue her. She cried to the police, “Let me through—that’s my husband!” The cop holding her back laughed. “That’s what all you girls say.”

While John was being asked to pose for photographs, to speak on this radio mike and that, he did manage to send a studio attache back for Patti. She came through the lane held open for her, smiling and trying to protect her new dress. “Pose with your husband,” a photographer yelled at her. She went into her prettiest stance.

The next day a tactful spokesman for the studio called on her and suggested that in the future she should wear a less conspicuous dress. “You took the attention away from John in the photographs.”

A situation like that is probably an old story to wise women like Mamie Eisenhower or Eleanor Roosevelt, but it was a bitter pill of realism for a pretty girl like Patti. She swallowed it, though. She didn’t mention the incident to John and she was certain he noticed that thereafter when they were out where spotlights would hit them, she wore the simplest black. He didn’t mention it to her either, but one evening before a big opening he brought home a great package bearing the name of one of Hollywood’s most famous custom designers. She tore it open. Inside was a dress that would have dominated Marilyn Monroe rolled into Hedy Lamarr rolled into Marlene Dietrich.

Patti broke down and cried. “Oh, darling,” she wept, “I’m not going to waste this on the public. I’m just going to wear it when we go out alone together.”

“Wear it tonight,” John said with a touch of grimness, “when we stay home.”

They were learning, both of them.

And the fans—John’s fans. Patti would have been less than human if her feminine jealousy hadn’t occasionally gotten out of hand when she read letters from girl admirers that said, “Please, please on this personal appearance tour, don’t take the plane. If anything happened to you, I would kill myself.”

Or, once the location of their home became known, the girls who came prowling around, hoping for a glimpse of John. Patti will never forget the morning some months after Russell was born when, wearing a beat-up pair of jeans, with no make-up and her hair piled up any old way, she was pushing Pablum down a reluctant baby throat. Two girls peered in the kitchen window at her, and one said clearly to the other, “Is that messy thing John Derek’s wife?”

“It took me a long time,” Patti says now, “before I came to realize that these girls didn’t love John enough to wash his socks or iron his pajamas. They simply wanted to adore him. John wasn’t conscious of them as females—as I was for much too long.”

Imperceptibly, so that they were aware of it only after they were able to look back over a period of years, marriage was changing both John and Patti—maturing them, helping them to grow. They quarrelled, yes—furiously. But even that was an advance, at least for John, who had never known how to express his own emotions. In the heat of an impassioned tirade, one night, he stopped, aghast.

“Why do I let my temper go so with you?” he asked. “I’ve never done it with anyone else in my whole life.”

Patti answered quietly, wisely. “Maybe because you know you can show any emotion to me—and it won’t change the way I feel about you.”

Among all the small milestones in the road of their life together, John and Patti remember some large ones. As for any couple, one is the birth of their first baby. Another is his near-death.

Patti was miserably ill during her pregnancy. The last four months before Russell (named for Russ Harlan, John’s devoted friend) was born, she spent in bed.

“That’s when I found out how wonderful my husband was,” she says. “He can’t cook. He bitterly loathes any form of housework. But he brought three meals a day to my bedroom. He scrubbed and cleaned and dusted like an expert.”

Then Russell was. born—with a separation of the esophagus. Only forty babies in the history of medicine have survived this condition. Russell is one of them. In the first twenty-four hours of his little life he underwent major surgery. He pulled through, and they were able to take him home. But he couldn’t be left alone a second. Four weeks after his birth, a nurse blew in his mouth to stop him from choking. His lung collapsed.

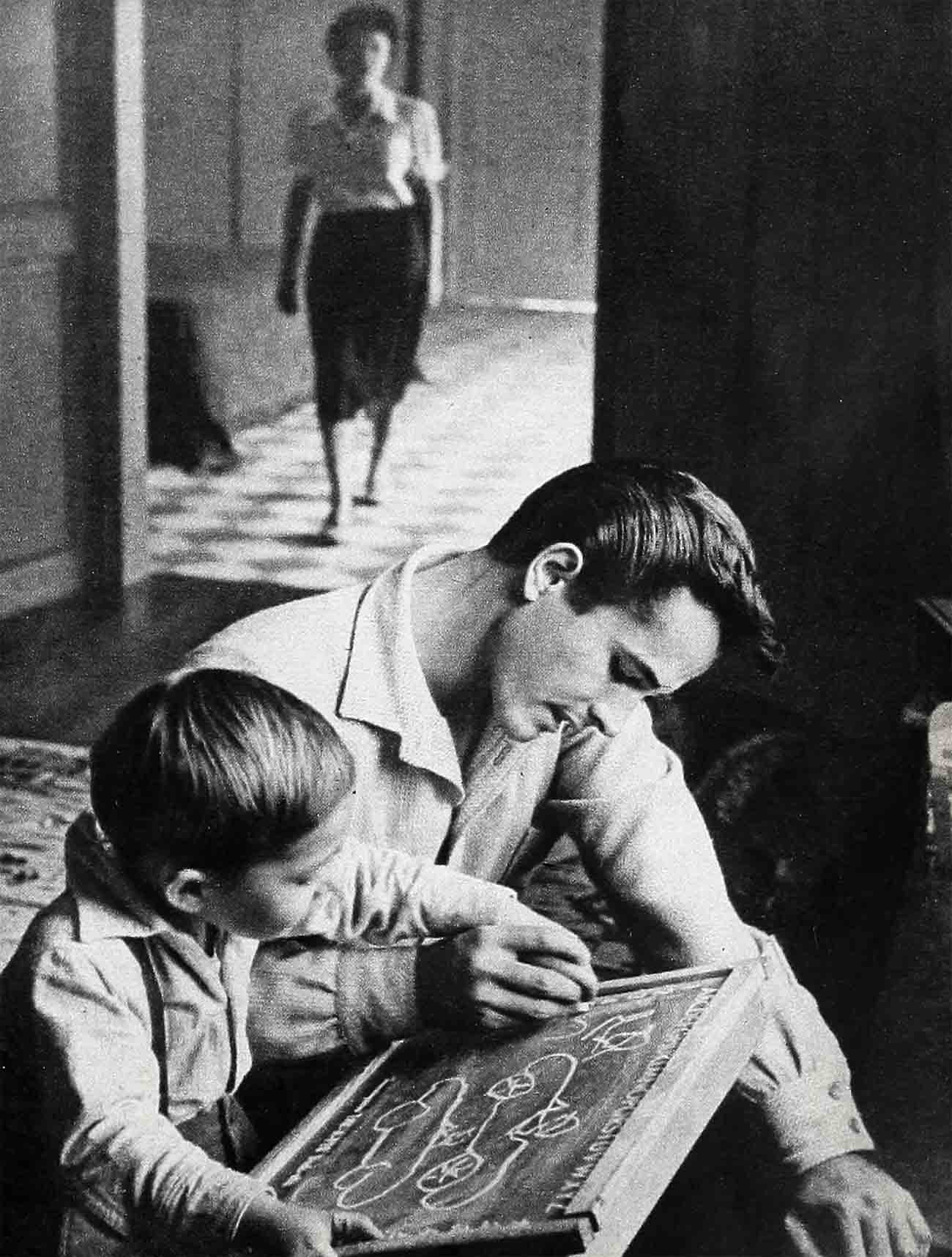

That’s when Patti gave up ail thoughts of ever resuming her career. The nurse was dismissed and Patti or John, one or the other or both, were always by Russell’s side. They forgot about parties, fun, the world outside. John left home only long enough to work, rushed back as soon as he could. The money disappeared. Their debts mounted. They ignored everything but their son and they saved him. Today, away from Santa Monica Canyon, out in the space and sunshine of the Valley, he is a healthy, happy boy. “Tarzan and Tarzan Jr.,” John remarks he and Russ swim together in the pool.

And now there is Sean Catherine in the nursery, strong as a little golden angel and just as beautiful.

With Patti’s whole-hearted support, John freed himself from the contract that made him unhappy and gained the right to work for any any studio he wants to—and that wants his acting services, of course. It is a bold adventure for a young actor, but it is what he wants, and that is enough for Patti. Already this new freedom has made it possible for him to give a brilliant performance in the TV presentation of “Place in the Sun.”

The Dereks, be it pointed out once more, haven’t two extra dimes to rub together. Their financial future is far from secure. But their emotional future is just fine. Not that they’re perfect, either of them. He still forgets wedding anniversaries and can’t seem to get it straight in his handsome head that Patti’s birthday is smack between Lincoln’s birthday and Valentine’s Day—“which ought to be easy for any man to remember,” Patti points out plaintively. And she is still very gingerly careful around horses, and won’t let Annie “be put away,” even if Annie is now a dog old before her time, crippled from an accident.

The thing is that they’ve grown from the impetuous youngsters who eloped to Las Vegas. They’ve found the way to grow and mature—they’ve found it in each other, the way it has to be found in any real marriage. They have no secrets from each other—their trust is too great. John now talks of buying a ranch in Arizona someday. “Okay,” Patti says. She wants more children. “We’ll have ’em,” assures John. “Who’s afraid?” And he smiles at her.

“Not us,” she says, and her answering smile to him is like a kiss, like a prayer and a benediction.

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE MAY 1954