The Gardner-Sinatra Jigsaw

PART II

The Gardner-Sinatra jigsaw, the pieces of which I believe will fit together in marriage before the summer ends, is not only a romantic jumble—it also involves two jumbled personalities. For both Ava and Frank are exceedingly contradictory characters.

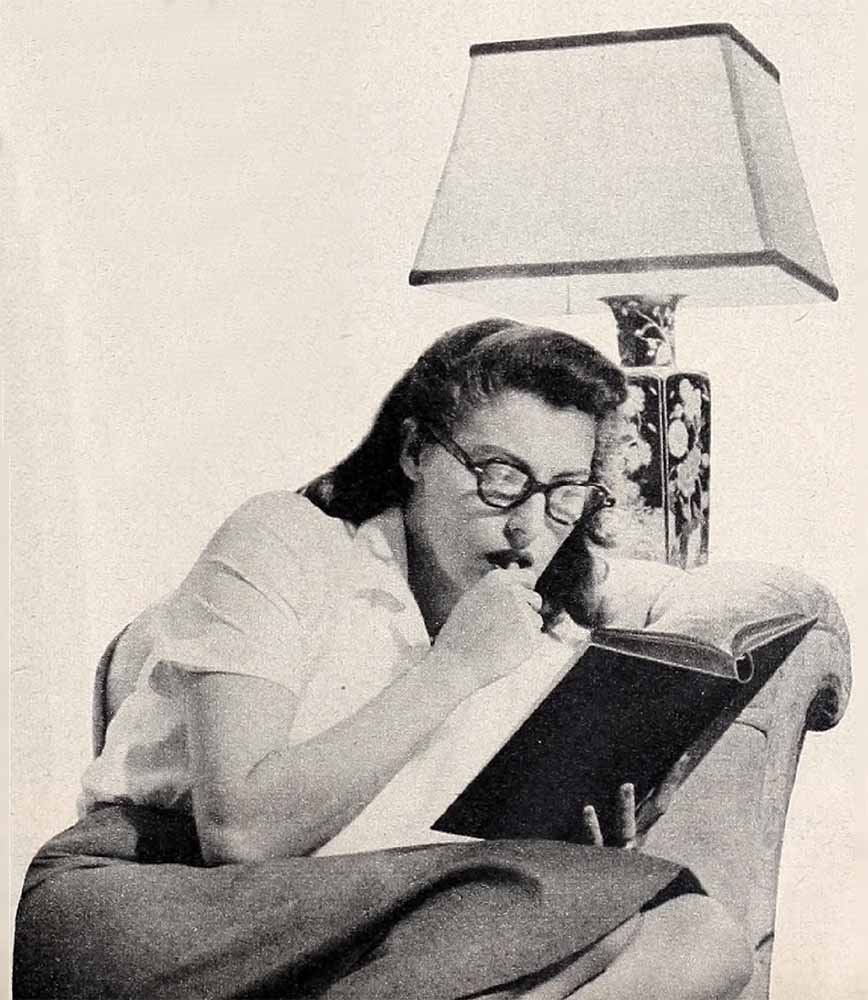

Ava makes frequent visits to North Carolina where her father used to farm the tobacco fields and where her sisters and brother and nieces and nephews continue to live in the simple surroundings which marked Ava’s childhood. Whenever life presses she goes home to Smithfield to get unsnarled. There’s no nonsense about these visits either. When Ava goes home she doesn’t live in any suite in any near-by hotel. She stays with one of her married sisters. She helps with the housework, tramps the countryside, talks to farmer friends, partakes of the local gossip at a country store owned by one of her sisters.

AUDIO BOOK

Basically, I think. Ava wants exactly what her brother and sisters have; a little house, a garden and a new baby as often as nature and the family budget will allow.

“For love and marriage and kids I’d give up my career like that!” Ava’s always said with a snap of her fingers. “Like that!”

I, for one, am sure she means it. But—and it’s a large but—there’s a strain in her which runs counter to this simple instinct. Otherwise she’d have stayed in North Carolina and married one of the young men of her home town or had some fluke of fate deposited her in the film colony she’d have been attracted to counterparts of the young men she knew at home. Instead, she married first Mickey Rooney, then Artie Shaw, fascinating fellows, it may be, but neither of them possesses even remotely the attributes of a steady husband.

And now Ava hankers to marry Frank Sinatra. Now, even though her career is on a brilliant rise, she continues to say she would give it all up—gladly. And on more than one occasion certainly she has jeopardized it for her love of Frankie.

I hope that under the dizzy influence of love Ava will not make this mistake. Ordinarily, I’m quite old-fashioned about marriage. But Frank Sinatra, let Ava face this, is no more blessed with husbandly virtues than were Mickey or Artie . . . She’ll do well, whatever happens, to keep her career as an anchor to windward.

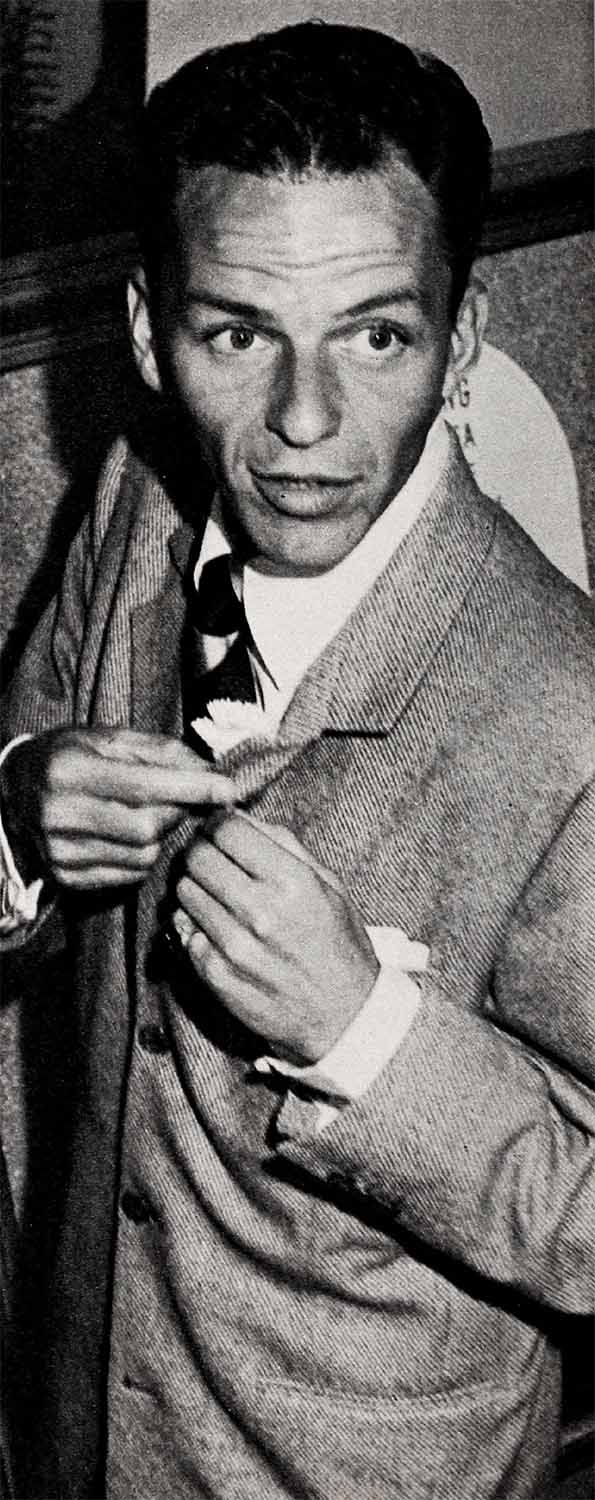

I’ve known Frankie for years. We met, as I said last month, in the first chapter of “The Gardner-Sinatra Jigsaw,” as implacable enemies when, after hearing him sing in a little cafe, I wrote dreadful things about him in my syndicated newspaper column. I criticized him because of the crowds of young girls, crowded on the sidewalk outside of the cafe and in the powder room inside, who were encouraged to squeal hysterically over him. Some of these girls were paid to squeal: Two dollars a night. But what began with commercialism grew with hysteria. I criticized Frankie, too, even more harshly, for the vulgar way in which he held the microphone.

So—when Frankie opened at the Wedgwood Room and I was a guest of Mr. Boomer who then owned the Waldorf, there was a great buzz. He has great charm, has Frankie. I still remember him approaching the mike that evening. “If I do not sing well,” he told his audience, “I ask your forgiveness. There are those here who do not like me. And when I am nervous I am not at my best.”

Later, at a party Mr. Boomer gave in his rooms, Frankie came directly to me. “You disapprove of me,” he said. “And my mother agrees with you. She said, ‘You tell that Miss Maxwell she is right!’ ”

“I disapprove of you, Frankie,” I told him, “only because I think it a pity for anyone with your naturally lovely voice to resort to such cheap tactics.”

“My press agent, George Evans, thought up the squealing girls and the way I hold the mike,” he explained. “I do not like any part of it. But it all has made the headlines. And the headlines have made me, I guess . . .”

He was so eager in those days. He sang at a White Elephant party for the benefit of Mrs. Taylor’s Child Adoption center at the Hotel Pierre at which I was to introduce him. And driving home in my car he held on his lap the little white fur jacket he had won and, again and again, picked it up to examine it, to admire it.

“Nancy’s never had a fur,” he said. “Is this real ermine?”

“No,” I laughed, “but it’s a reasonable facsimile.”

I say again that I do not doubt Frankie has associated with wrong people in his time and done wrong things. In the nightclub world there is plenty of opportunity for both. Frankie’s inherently tough, a product of the Italian section of Hoboken where he grew up. And, inclined to be bitter about his underprivileged youth, he wants boys growing up in similar neighborhoods all over the country to have a chance to become good citizens. But he lacks the background or the knowledge to judge where liberalism ends and other “isms” begin, including those isms which our underworld uses for its own evil ends.

It would take a corps of psychologists to understand Frankie—his restlessness, his complexes, his deep insecurity and, above all, his rebellion against authority. Arrogant and hot-headed, he hurts many associated with him. Frequently, however, these people remain staunchly on his side.

Nancy has forgiven his romantic truancy so many times. And her mother, even now, will let no one speak against him. She still thinks of Frank as the skinny, ambition-driven teenager who, visiting Nancy, used to borrow money for carfare.

Recently, when Frankie finished retakes on “It’s Only Money” and signed to appear at the Copacabana in New York and needed special material, his first thought was of a writer with whom he had had a frightful row. “Get in touch with Joe,” he told his secretary. The secretary located the writer in Palm Springs to find he already had the material prepared. “I thought Frankie might be needing something,” he explained. “I’ll be in Los Angeles in four hours.”

Maxine Arnold, one of my colleagues on Photoplay, has her favorite Sinatra story too—about the time they wanted Frankie to go to Phoenix, Arizona, and put on a show for the Junior Police kids. Maxine took the junior officer to the radio studios where Frankie, shuttling back and forth between two radio shows and rehearsals, was eating a fast sandwich. He could have told them all to get out. But he pulled out his little pocket calendar and put a ring around a date. “Let’s make it then,” he said.

He explained to the Junior Police officer that the latter might not hear from him again—but he’d be there. However, when the boys didn’t hear they got panicky and checked with his press agent, who knew nothing. But, he said, that date was checked on Frank’s desk calendar; so Frank, who was in New York, undoubtedly knew all about it. And sure enough a few days before the date came around Frankie called from New York to say he was bringing a show with him.

“But we can’t pay for that kind of talent,” the officer protested.

“Who said anything about paying for it?” demanded Frank. ‘I’m bringing them.”

And he brought Sid Caesar and The Pied Pipers.

These are the stories Ava likes to tell I about Frank. She’s impressed, too, with I his devotion to his children, Nancy, eleven—Frank, seven—and Christina, three, and their great love for him which their mother has protected magnificently.

When Nancy went to court for her separation agreement she turned away from the TV cameras. “After all,” one of the photographer challenged, “I’ve got a wife and kids to feed.”

“I have children too,” Nancy replied, “and they look at TV.”

It was about nine months ago that Nancy sued for her separation. Since then she has said, repeatedly, that she has no intention of asking for a divorce. She is not interested in any one other man, certainly. Her dates with Bob Sterling and other Hollywood gentlemen have been casual.

However, recently she and Barbara Stanwyck have become good friends. It could be that Barbara, who made a valiant effort to hold her marriage with Bob Taylor together before she admitted defeat in the divorce court, will convince Nancy that when a marriage is over it is wiser to let a man go, even though you do not want freedom for yourself.

And now I come to the two last pieces in the Gardner-Sinatra Jigsaw. There has been talk Frankie would like to return to Europe—to Spain especially—with Ava as his wife. He hopes, I suspect, to erase his memories of last summer when, a married man, he could not deal with the romantic rumors about Ava and toreador Mario Cabre—who appears with her in “Pandora and the Flying Dutchman”—as he would have liked to do.

Hearing this talk, I called Frankie on the phone. “I do not mean to intrude upon your private plans,” I said, “but I understand you are hoping to marry Ava. And if I could know the time of your honeymoon I would like to arrange a wonderful party for you—in Spain. I know many interesting people there. Last year my Spanish friends complained because they neither saw nor heard you . . .”

“I would love such a party,” he said enthusiastically. “But it could not be until late summer . . .”

Ava’s friends continue convinced that she never will agree to any irregular marriage. But an acquaintance of Frank’s, who knows how persuasive he always has been with Nancy, wouldn’t be surprised to see Frank, when the time is right, convince Nancy that since they grow further apart all the time and since he truly loves Ava, a divorce is in order.

When this happens the last piece in the jigsaw will fall into place.

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JULY 1951

AUDIO BOOK