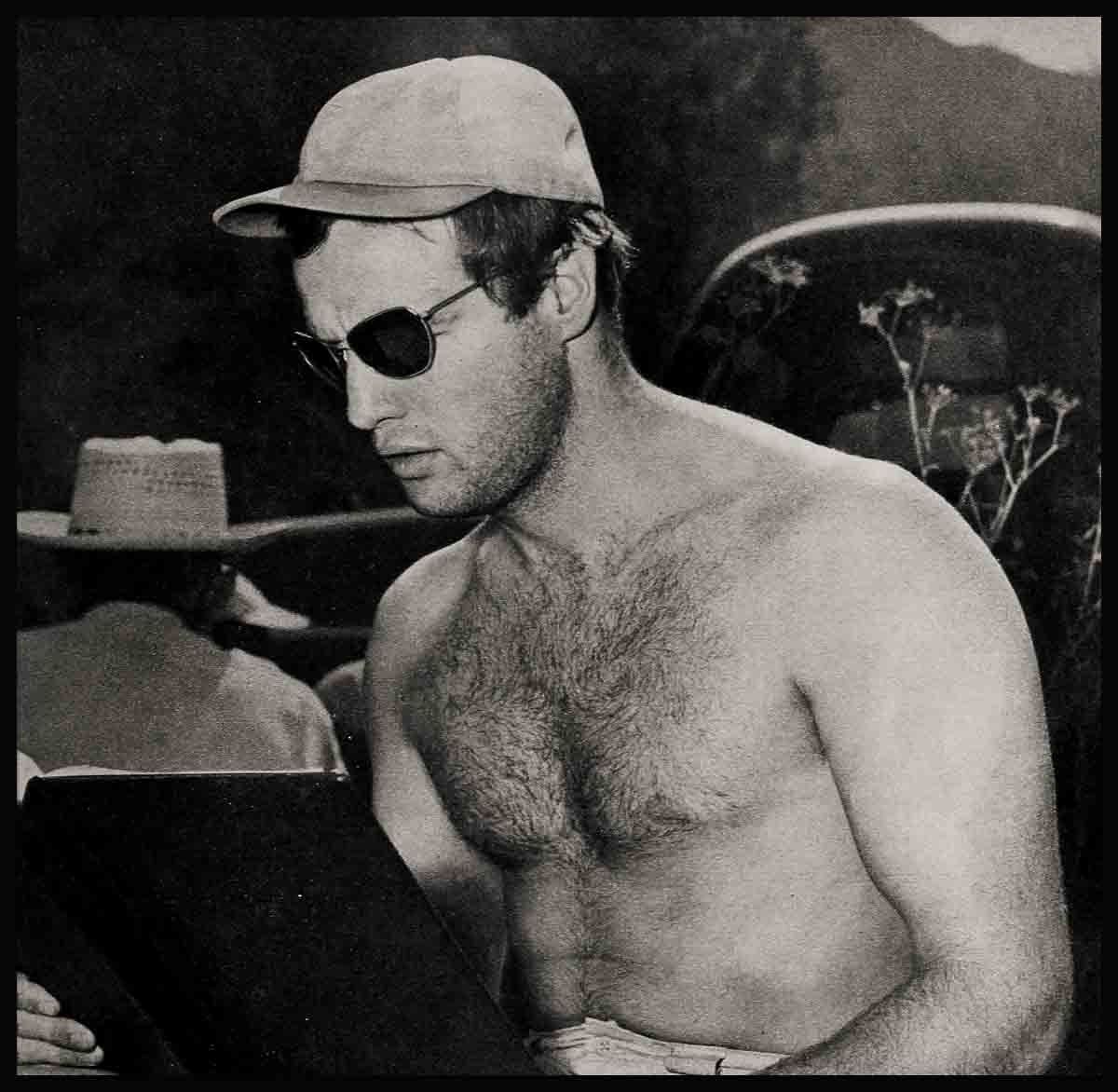

At The Top And Quitting—Marlon Brando

Marlon Brando has had it!

After only five motion pictures, The Men, Streetcar Named Desire, Viva Zapata, Julius Caesar, and The Wild One, the 29-year-old acting genius from Omaha is kissing Hollywood goodbye.

“I came out to Hollywood for two reasons,” the brooding, hawk-nosed eccentric recently explained, “loot and film experience. I’ve got ’em both, and there’s no point in hanging around. Maybe I’ll do Pal Joey, but right now I’m not sure.

“Only thing I’m sure of is that I’m getting out. I’m going to travel, maybe do some pictures in Europe. I want to go to the Far East, Siam, India, the South Sea Islands.

“Maybe later this year I’ll blow back to New York. Maybe do a show for Cheryl Crawford. Maybe just keep going, just keep strumming that guitar.

“I’ve got nothing against Hollywood. It’s been very good for me working here. It’s broadened me socially. I’ve learned a lot about the business. But it is a business, and when you’ve made enough loot, the thing to do is pull out.

“I like to travel, and I’d just as soon spend some of my dough while I’m young and can enjoy it. I’m not finished with motion pictures. I’ll make more of ’em, only maybe not in Hollywood. They make some pretty good stuff in Europe and I wouldn’t mind working over there. Also wouldn’t mind taking a crack at directing.

“I just don’t dig this Hollywood routine any longer. When I first came out here, I was very shy, didn’t know what gave. Bunch of people started asking me wacky questions. I didn’t tumble to ‘em. I just mumbled or kept quiet. Right away, they pegged me a screwball. Made up the most preposterous stories about me. A bunch of scuffing hucksters, nothing else.

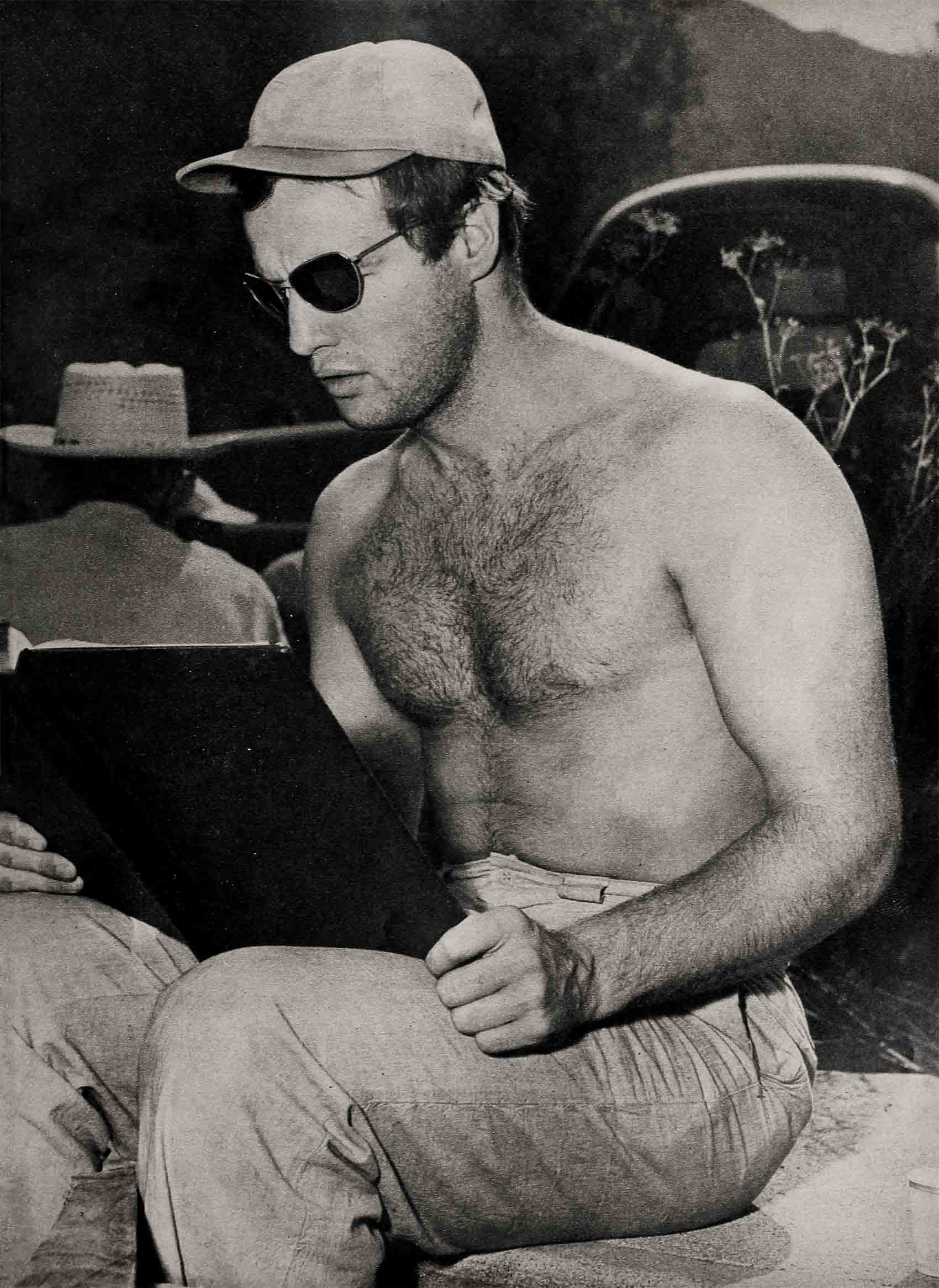

“All that stuff about my clothes, blue jeans and T-shirts. Must be a million guys in this country wearing blue jeans. They’re nice and comfortable. I’ve got suits, ties, shirts, things like that. I’m not the screwball they write about. I’m not out of this world. Just because I keep a raccoon. What’s wrong about keeping a pet? What’s wrong about playing with a raccoon? I just happen to dig animals.”

In three years of film work, young Brando has managed to save approximately $200,000, a sum prudently invested for him by his father in a holding company aptly named Marsdo, Inc. (Marlon’s dough).

This company has interests in several Indiana oil wells plus owning outright 800 head of class A cattle in central Nebraska. It is estimated that Brando’s dividends will now bring him an annual income of $10,000 which is more than enough “loot” for the most unHollywood-like actor in existence. Thus, if he never works again—and for him this is an impossibility since acting is really the great passion of his life—Marlon will still have enough of the green stuff to get by comfortably.

Brando has been able to amass this. financial nest egg by being honest, sensible, thrifty, frank, earthy—and you may not believe this—but completely unaffected. This boy believes in the essentials—nothing else.

Brando’s opinion of the “glamor life” is unprintable; and he saw through the glitter of Hollywood at once. He recognized immediately what a perfect environment this was for a fool to be quickly separated from his money.

First thing he did was to move in on his aunt, Mrs. Betty Lindemeyer, who owns a two-bedroom bungalow in a small community called Eagle Rock. He slept on her sofa.

Now, oddly enough, many Hollywood actors wear blue jeans and T-shirts. and dress most informally—Dale Robertson, Bob Wagner, Dan Dailey, John Derek, many others—but the Press typed Brando “a wack” very early in the game and never let up on him; and as evidence of what they termed a strange behavior pattern, they pointed to his scanty wardrobe, also his incommunicability.

None of the reporters who first interviewed Brando entertained the possibility that he might be afraid. After all he was so broad-shouldered and masculine. He seemed to generate so much animal sex. But the truth is that he was plenty afraid.

“One columnist started to talk to me,” he recalls. “She was very nice but she chattered so much I couldn’t follow her, so I just didn’t say anything.”

Then, there was the time Brando was playing in Streetcar Named Desire. A friend brought another Hollywood columnist, backstage to meet him. At the time Marlon was busy taking his make-up off. Catching only a quick glance of the newswoman, he turned to his friend and said, “Your mother, Jesse?”

The reporter is far too young to be the mother of a 30-year-old son, but on this particular night she looked worn, and Brando hadn’t gotten too close to her. As a result of his offhand remark, Brando is not one of these ladies’ favorites in print.

Actually, Brando is so honest he’s amazing. He says many of the things most people wish they had the courage to say. A few years ago, for example a newshen began to interrogate the young actor about his sex life. Brando was so genuinely shocked, this seemed like such a flagrant invasion of his privacy, he could call to tongue only one answer. “None of your damn business,” he rightfully said. Whereupon the writer next day described him as “a strange, withdrawn mental recluse.”

A studio chauffeur once called for him in a limousine, offering to drive him from the railway station to his residence. Brando looked at him quizzically. “Been sitting a long time,” he said. “Rather walk.” He detests any ostentatious display of wealth.

What many people don’t seem to realize—it doesn’t fit into the build-up and they refuse to accept it—is that Brando is blessed with a highly imaginative and romantic sense of humor although basically it is more adolescent than adult.

When he was making Viva Zapata he told one of the crew, “You know when I was in the Belgian Congo I used to eat gazelle eyes everyday. The natives mash them up into a paste. Very good.”

Brando has never been in the Belgian Congo but he was secretly tickled when members of the crew fell for the story. Later he admitted, “I just made that up.”

In New York, very early in his acting career, when he played the role of Nels in I Remember Mama, he was asked for some biographical notes to be printed in the program. Brando thought for a while, then announced that he’d been born in Calcutta, that his father was an itinerant geologist, that he’d been educated in India.

Later, when he acted in other plays, he changed his birthdate, altered his birthplace to Bangkok, spun a romantic story of how he had lost a passport in France and had been compelled to earn a living disguised as a Turkish beggar.

“Reason I did it,” he explains, “is that those programs are always so dull. Wanted to jazz ’em up a bit.”

Dozens of stage actors have long confided that they, too, hoped one day to fabricate romantic autobiographies; but to date, Brando is the only one with sufficient courage to be seduced: by his impulses.

Reporters cannot understand other facets of the Brando behavior. Why, for example, does he steer clear of the Hollywood beauties? Dozens of glamor girls ha tried their best to date him. They’ve worked through intermediaries and friends of Marlon, but the boy won’t give them a tumble. He is more interested in the mind than in the body.

He goes with the actress, Movita, more than he goes with any one movie star, but that’s because he doesn’t consider her the typical product of the Hollywood beauty belt-line. He likes simple, forthright girls and is more interested in their manner and attitude than in their fame or beauty. Also, he cannot abide publicity-seekers, male or female.

“He always used to go with a cross-eyed girl or an ugly-duckling in school,” his mother recalls. “He’s a boy of great sympathy and rare compassion.” And this is no maternal exaggeration, either. Brando is. inherently kind.

Actresses who have worked with him say that he gives every scene his best, never essaying to steal a scene with a clever little distraction or to block someone else out of the camera. He is completely devoid of deceit or narcissistic thinking.

Teresa Wright, who played opposite him in The Men, says, “Marlon is one of the finest, most thoughtful actors in the business. I love to play opposite him.”

Elia Kazan, who’s directed Brando both in New York and Hollywood, describes him as, “the greatest young actor in a century.”

Mary Murphy, his leading lady in The Wild One, claims, “He’s the tops. He’ll do anything to help you. In this whole picture I have yet to hear anyone say a single bad word about Marlon. He’s cooperative in everything.”

The girls who speak in derogation of Marlon are usually those he’s spurned. Before she got married to Vittorio Gassman, Shelley Winters was sweet on Marlon. For a long time he refused to look at Shelley because he felt she was putting on. A few weeks later when they met at Motion Picture Center and Shelley came down to earth, Marlon took to her very nicely.

A few months ago, Brando was at a party where one young actress—she’s popularly referred to as Hollywood’s newest sex queen—tried to attract his attention by showing more and more of her neckline. Brando has a powerful sense of concentration, the result of studying Yogi, and he refused to flatter the doll with even a sideward glance. Later, the offended sex queen described him as, “the most insufferable prig I’ve ever met.” To this very day, Marlon doesn’t even know she was at the party.

When he likes a young woman, however, he makes no secret of the fact. During the making of Viva: Zapata which was shot on location in Del Rio, Texas, he got on famously with Jean Peters. To show exactly how fond he was of this beauty, he climbed a treetop and serenaded her at three A.M.

Brando is a free soul who has always believed in obeying his impulses. He was expelled from school because he felt he simply had to wire the classroom doors with explosives. Next morning his teachers were duly shocked. His classmates, however, thought so much of their quixotic colleague that they signed a petition demanding his immediate reinstatement.

By this time, however, Marlon was fed up with school and took a job north of Chicago digging irrigation ditches. A few weeks later he moved-on to New-York where his sister Frances was studying art in Greenwich Village. He decided to become an actor and enrolled at the New School for Social Research where his dramatics instructress was Stella Adler.

After a year at the New School and a season of summer stock on Long Island Brando was signed for I Remember Mama. Four plays later he was cast as the lead in Streetcar and after that, Hollywood beckoned and he came.

Brando was paid $45,000 and ten per cent of the profits for his work in The Men. In Streetcar he got $65,000. Viva Zapata! was good for $75,000. Julius Caesar and The Wild One brought him $100,000 each.

In five pictures, Marlon has grossed close to $400,000, approximately half of which he’s given to the government in taxes.

When Marlon is working, all of his salary is sent to his father in Chicago. His father, in turn, sends him $100 each week. Added to this, Brando gets $50 a week from MCA, the talent agency that represents him.

“On 150 bucks a week,” the actor says, “I get along very well. I have everything I want in the way of food, shelter, and entertainment. When I want to travel that’s when I dig into the big loot. In Hollywood I try to rent a place, a house or something, that gives me a little privacy. In New York I have an apartment on 57th Street near Sixth Avenue. Nothing very big.”

Actually, Marlon comes from a fairly well-to-do family. As a child in Omaha, Evanston, and Libertyville, these last two cities in Illinois, he always lived in large homes—there were never less than two in service—and he was sent to Shattuck, an expensive military academy.

With this sort of background it’s a tribute to his sense of values that he understands the worth of a buck in this world. He believes more in the luxury of the mind than in luxurious material possessions of which he has practically none.

A friend who’s known him for many years says, “They can call Bud a wack, a screwball, a bum, anything they want to, but do you know any youngster in Hollywood who’s handled himself better? In three years this kid has been starred in five of the best films. He’s won all sorts of critical accolades. They gave him an Academy Award nomination for Zapata, and I predict he’ll get another one for Julius Caesar.

“In three years he’s earned enough dough to take care of himself for the rest of his life. He’s never been mixed up in the slightest scandal. He’s never been arrested for drunken driving or slugging a cop or any of the mistakes young guys are more or less e to make.

“His head hasn’t swelled one-eighth of an inch. If anything, success has made him more kind, more thoughtful, more considerate. He’s been a good son to his parents, a good brother to his sisters and a good friend to his friends. The only people who dislike him are reporters he refuses to see on the grounds that they’re ‘scuffling hucksters’.

“I’m not saying he’s perfect. He’s got a lot of blind spots. Like he’s death on movie magazines, hates them, but not without reason. A lot of them have made him look like a silly jerk, and the truth is that he’s not.

“In a town of sophistry and sophisticates and snow-job artists, he’s managed to hold his own by being honest, frank and outspoken. By being Brando, nobody else.

“If you know any other kid who’s got a better record than Bud, who’s made a better showing than him, I wish you’d speak up.

“This guy doesn’t miss a trick. He’s got all the right instincts. He’s leaving Hollywood exactly at the right time. He’s 29, and he’s on top. That’s the time to pull out—when you’re on top.”

THE END

—BY STEVE CRONIN

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE JUNE 1953

No Comments