The Heart Has Reasons—Ingrid Bergman

On the hottest days of the hot Italian summer, the roads from Rome are choked with dust. Dust coats the ripening wine grapes. It laces the black bread and cheese that the peasants carry and sifts into the wool of their grazing sheep. Towards evening it swirls above another flock—of sleek Maseratis, Ferraris and Alfa-Romeos.

On such an evening, Ingrid Bergman retreated from Rome to her villa at Santa Marinella. Like the dust she was swept along by an ominous eastern wind. The tires of her white Ferrari traced a single word across the miles of uneven brick road:

Ro . . ber . . to. Ro . . ber . . to. Roberto.

Past the shepherds. Ro . . . ber . . . to. Past the sheep. Ro . . . ber . . . to. Past the olive orchards. Ro . . . ber . . to. Past the vineyards of muscats and tokays, spicing the twilight with all the ripe smells of summers gone and summers lost.

She drove too fast. The Ferrari lurched in protest.

Roberto had always driven too fast. This car was his “summer Ferrari,” yet four times he had raced it through the mountains n January and gotten stuck in a snowbank and spent the night curled on the floor underneath a fur blanket. Inside this car he had forgotten all his problems. With those sensitive hands of his barely touching the wheel he had seemed almost drunk on speed. Speed relaxed him. How many times had she watched him smile as the speedometer edged past 110, past 120, past 130?

She pressed her foot down on the accelerator. The speedometer needle quivered near eighty. But she was no Roberto. She could not forget the reporters.

“Miss Bergman, what is really happening between you and your husband?” “Miss Bergman, what will you do if your husband brings Sonali Das Gupta back to Italy with him?” “Miss Bergman, has Rossellini asked you for a divorce yet?”

She could not forget the photographers. Two weeks ago the photographers had turned into a public carnival the first tentative, tender meeting with the nineteen-year-old daughter she had not seen in six years.

“Give us a shot kissing your daughter, Miss Bergman. A big kiss. You’ve got six years to make up for.” “How do you feel about your mother, Jenny? Are you really glad to see her?” “Don’t pay any attention to us, Miss Bergman. We’ll be following you around all afternoon.” “Sorry if these questions are too personal, but my editor wants. . . .” “Just one more shot.” “Just one more statement.” “Just one more.” “Look this way, Miss Bergman.” “Miss Bergman.” “Miss Bergman!”

Remembering, she felt her cheeks burn with anger and shame. To bandage the wounds of the last six years would have been difficult enough in private. But their only privacy had been fourteen minutes alone together at the Paris airport—locked inside the DC-6 that had brought Pia Lindstrom to Paris. Not “Pia,” Ingrid corrected herself guiltily. “Jenny Ann” Lindstrom now. She wondered if she would ever remember her daughter’s new name.

For the moment they had left the plane the world had trotted at their heels, capturing each of their tears for the morning newspapers. What a fever of excitement she had been in. She had clutched Jenny’s hand as though afraid that—if she let go—Jenny might vanish. She had wanted to show Jenny her Paris. The shops. (She had refused Jenny nothing. Clothes. Shoes. Perfume. Paintings. Even the things that Jenny did not ask for except with her eyes.) The Eiffel Tower. (They had scorned the elevator and climbed the tower on foot and leaned together—breathless—over the railing at the top.) The bookstores. The art shops. The Seine. Jenny had been cool and calm, flattered by all the reporters and photographers and curiosity-seekers who dogged their footsteps through the streets. How long, Ingrid wondered bitterly, had it been since she had been flattered by these things?

It was on the cobblestone banks of the Seine that she had been cornered—like an animal—by a pack of photographers and pushed towards the river. She had turned on them then and shouted angrily, “Can’t you leave me and my miserable life alone?”

She shifted the Ferrari into low gear. Ahead—where the road curved—she could see the lights of Santa Marinella. Already the fishing boats rocked in their anchorage at the foot of the village, and the smell of the day’s catch was heavy in the summer air.

She was sorry for the rage that had forced her into shouting back. In all the tormented, uncertain weeks since May—when the first rumors had drifted out of India—it was the only time she had lost the dignity and courage with which she tried to keep herself dressed in public. (But why was she always being asked to meet life with courage? How much courage must one person have? How much courage could one person have?) She had tried to laugh in answer to all the questions. “There is no truth to the rumors of trouble between my husband and myself,” she had said. “Soon I am returning to our villa at Santa Marinella. My husband will join me there when he finishes the films he is making in India.”

She let the Ferrari coast towards the big white house at the edge of the sea. She did not yet know, herself, whether she had told reporters the truth. Would he return—sunburnt from the long months of Indian sun and hungry for spaghetti and bread and kisses? Or would she wait here endlessly, looking through the window for a man who would never come? Or—the thought trembled at the edges of her mind—would she move on alone, leaving this place behind her as she had left so many cities, so many countries?

How many cities had she called “home”? Stockholm. Rochester. Hollywood. New York. London. Paris. Rome. Santa Marinella. Life had never been something smooth and finished for her—silk or velvet. It was, instead, a . . . a . . . sweater . . . that she was knitting from an obsolete pattern. When she managed to pick up the stitches at one end, fate took a perverse pleasure in unraveling them at the other. When she had been rich and famous, her marriage to Peter Lindstrom was ashes. When she had had Rossellini and love, the world was lost to her. When she had borne three new children, her first child was taken away. Now she had painfully reacquired glory and applause. The world had returned, sweeping around her feet like a tide. All four of her children slept tonight under the same roof. Would love be the stitch to be unravelled?

She shook her head free of these fancies and slid out of the car. The thoughtless, automatic movement held unconscious grace. At forty-two she still retained the firm, well-balanced body of an athlete. At forty-two her beauty was still perfect.

The house was cool and dark—untroubled by uneasy dreams; its only sounds the whirring of the electric clock and refrigerator. In the hall she hesitated. She had spent six summers in this house and yet tonight it seemed strange to her. It was too calm and peaceful without the electricity that Roberto brought to it. An empty house without his sudden anger spilling fury into its rooms, without his equally sudden tenderness.

Was he already on his way back to Santa Marinella? Would the telephone ring and his voice suddenly pour into her ear from Rome? Would his key turn in the lock? Or was he already on his way someplace else, with someone else?

She pushed a strand of sun-bleached hair from her eyes and moved softly down the hall—as she had done so many times before—to check the sleeping children. She paused for a moment in the doorway of each room.

Robertino. Blue-eyed, fair-skinned, his face calm and enigmatic, he looked like . a Swede. Yet all the fury of his father lay beneath that fair skin. How often, she wondered, did a face belie the true spirit?

The twins. Ingrid—curly-haired and brown-eyed—looked enough like Roberto to cause a sudden pang. And yet she alone of Roberto’s three children was calm, affectionate and Nordic. Isabella moaned restlessly. But she had no fever, and the scar from her emergency appendectomy of a month before was healing well. Another blue-eyed, straight-haired miniature of her mother, she, too, was driven by all the Latin devils that drove her father.

Pia. It was in this room that Ingrid lingered the longest. She had brought Pia—Jenny, she corrected herself—to Santa Marinella for the summer. “This summer I will have all four of my children together at last,” she had told a reporter. And yet, Jenny was no longer a child. Too big to be mothered and petted and pleased by promises of bedtime stories. Eight years ago Pia had been a child. (It was strange how her thoughts wandered tonight. They were like boats drifting on currents she had no power to control.)

That was the first winter she had known Roberto Rossellini. There had been no thought or talk of love between them. He had come to Hollywood to raise money for “Stromboli,” and she and Peter had invited him to stay in their guest house. On the last day he had borrowed $300 from her. “For expenses on the way home” he had said. Then he had spent it all on gifts—ties for Peter, an alligator traveling case for herself, and—for Pia—a three-foot-tall stuffed cow. Pia had wanted that cow for weeks, but it had cost $75 and Peter—quite reasonably—had refused to pay $75 for a toy. When Pia unwrapped the gift, Ingrid had been so moved that she had cried.

That winter of 1949 was almost the last time she had seen Pia. In March she had left for Stromboli. There had been one short visit in Sweden in 1951 and then only memories too bitter to be forgotten even yet. She had waited for Pia in the summer of 1952, but Peter had refused his permission. He had taken Pia to court and put her on the witness stand. And Ingrid—during the last week of the ninth month of her pregnancy—had read the clipping in the morning paper.

“Don’t you want to see your mother?” the lawyer had asked.

“Why I just saw her last summer.”

“Don’t you love your mother?”

“I like her, but I don’t love her.”

“But you always sign your letters, ‘Love, Pia.’ ”

“That’s only a way of signing letters.”

“Don’t you want to live with her?”

“No, I want to live with my father.”

Two days later Ingrid had given birth to the twins. She had been so afraid that the baby would be a boy. She had expected a boy—(a sign that the gods were still angry with her?). And she had felt so rich with wonder and gratitude that she had been given two girls to ease the pain of the one she had lost that she noticed little of the pain and complications and surgery and blood transfusions that followed the twins’ birth.

She had never wanted the twins to—never allowed them to—replace Pia. Among the photograph albums that she kept in a special cupboard were seven covering Rome and Santa Marinella and the years of her marriage to Rossellini. In each of these seven albums were pages that she had left blank—pages to be filled one day with pictures of Pia taken during the years of their separation.

The albums themselves had been started long before her marriage. The first one had been begun by her father. Later she kept them—filling each book with pictures and souvenirs and newspaper clippings and neat, typewritten comments to herself.

It had been a long time since she had looked at the albums. She suddenly wanted to see them again—to trace through their dusty pages the tangled web of her life. (As though, somehow, the fading photographs could explain why she had always had to experience life to the fullest. She remembered that someone had said of her once that: “A long time ago Ingrid crossed the line from living for security to demanding everything that life can offer. And once you have crossed that line you can never turn back.” Had she really crossed that line or had she been born on the wrong side of it?)

She sat down in the deep red chair and reached forward to take the first volume from the shelf. . . .

STOCKHOLM 1917-1940

Red was her favorite color. It had been her father’s favorite color too. The first time he had taken her to the theater she had worn a red dress. There was no photograph of that day except the one she carried in her mind. She was eleven years old. And the red dress had been lent by her aunt and pinned in until it almost fitted. “Patrasket” was the play and each detail of it—and of the day—would be part of her forever. The musty, safe smell of the theater and the rustle of taffeta below and her exact seat in the box in the first balcony and—above all—the rapture. It was on this day that she decided to become an actress.

How few pictures there were of her father. And only one peeling photograph of the mother who had died when Ingrid was two. Perhaps her father had taken that photograph. Justus Bergman had been a successful photographer. But he had wanted, instead, to be a great artist. He had always used red in his paintings, telling Ingrid that “Red is the color of life.” Perhaps he ached to capture life on canvas because his own life would be so short. He died when his daughter was thirteen.

How awkward she looked in that photograph, standing there with her five cousins. She was all head and neck and feet, even though she was bending her knees to seem smaller.

There were her aunt and uncle—good people, but stern-faced and forbidding. After her father’s death she had been passed from family to family before coming to live with them. They had fed her and bought her wool leggings for the winter and put braces on her teeth when she was fifteen—but they had never called her by a pet name.

At fifteen she was too tall, with a long, thin body that seemed to her to stretch to the sky, and too shy ever to talk above a whisper unless she was pretending to be someone else. Perhaps that was what had made her so successful an actress. She had always been able to wriggle into other personalities and fit them comfortably on top of her own skin. She was only uncomfortable when she had to be herself.

That phonograph her cousin was leaning against was the one that belonged to her. Her uncle did not approve of acting and so she had bought the phonograph and a dozen loud records. She had read plays aloud in her bedroom while the music from the phonograph drowned out her voice. There was the night her uncle had discovered everything and torn the book from her hand.

But she had forced him—had she really threatened to commit suicide?—to let her compete for the Swedish Royal Dramatic Theater’s annual scholarship. How her cousins had laughed. But she had won the scholarship easily. That night she had told her uncle:

“Now the whole world is open to me.”

And then the world had suddenly been full of Peter. Page after page was filled with the tall, blond dentist who was studying at night to become a doctor. Handsome, meticulous, and at ease in the world, he was eleven years older than the sixteen-year-old dramatic student. When the first film offers came, it was Peter who took charge. For the first time since her father died, she had someone to lean on. Their wedding picture: “Peter and Ingrid Lindstrom. July 10, 1937.”

ROCHESTER, NEW YORK, 1941-1943

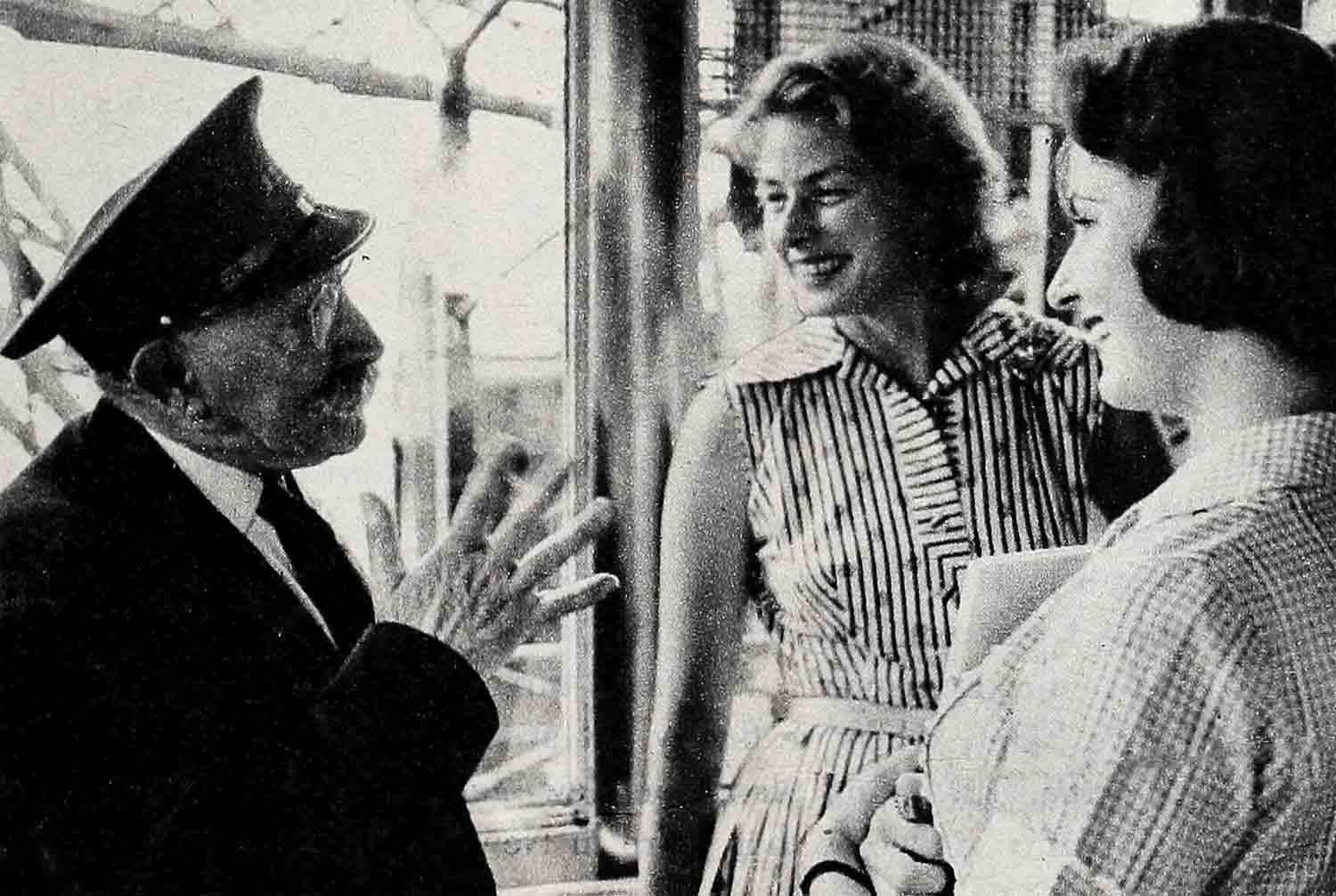

No one was at the boat the first time she came to America—to make “Intermezzo” with Leslie Howard for David O. Selznick. But after “Intermezzo” she was a star and photographers were waiting when the boat docked. There was the picture they had taken of two-year-old Pia slung over her shoulder in a wool-lined knapsack.

This was the University of Rochester where Peter would finish his studies. And this, the house where they lived. (How restless she was during the months she spent in Hollywood making movies and how eager to get back to that house.)

And there was the first newspaper clipping:

“Picture the sweetheart of a viking, freshly scrubbed with Ivory soap, eating peaches and cream from a Dresden china bowl on the first warm day of spring atop a sea-scarred cliff and you have a fair impression of Ingrid Bergman. This incredible newcomer from Sweden wants to play a fallen woman, though her ability to go that far is herewith doubted. She just hasn’t the face for it.”

Ingrid looked up and stared into the mirror across the room. The face was almost the same, seemingly unravaged by the blows that had rained down on it in the years between. It was a little thinner perhaps, the skin near the eyes more drawn, the baby roundness of the cheeks tightened over fine bones. But those were the only changes. The face. The incredible face. It was—perhaps—the cause of all her troubles with the world. Without her willing it or wanting it—or even, for a long time, knowing that she had it—that face was the embodiment of innocence, of purity. It was the face—and not the roles she had played—that had misled people into putting her on a pedestal. It had hypnotized even the cynical experts in Hollywood.

“Gaslight” had won her her first Academy Award. But when she had fought for the part, the experts had at first refused and spoken of “the neurotic wife—a role as unlike Ingrid Bergman as possible.” Of another role, Joan Madu in “Arch of Triumph,” they had asked, “How can Bergman play this frustrated, hopeless woman? Bergman is too normal, too sweet to interpret this character who achieves nothing and never solves the problem of her own life.”

The face, Ingrid thought, turning away from the mirror, was the face for a saint—and no human being can live up to the face of a saint.

HOLLYWOOD 1943-1947

NEW YORK 1947-1948

This was a snapshot of her home. “The Barn”—a house of stone and rafters rising in the hills above Beverly Hills. Two acres of land surrounded the house and lapped it in peace. Two acres where she could walk and no human voice would follow her. (Roberto—all the Italians—liked to cluster together. But she had always needed time alone. Once—at a weekend party—she had felt trapped in a roomful of people. “Lend me some shoes,” she had said to her hostess. Slipping the shoes on, she had left the room and walked alone through the afternoon.) Perhaps walking was the thing she liked best in life. With a bag of fruit under her arm she had roamed the streets of New York like a schoolgirl. It was on one of these trips that she had first come across the name of “Roberto Rossellini.” In a small theater on West 49th Street she had seen the film “The Open City.” She had been impressed and when she left the theater she had looked at the posters outside and found that it was directed by Rossellini.

The albums for these years were thick with clippings and awards. These had been the most successful years. In Hollywood there was a joke during the winter of 1945-46. “Guess what?” one man would say to another. “I just saw a picture without Ingrid Bergman in it.” That year “Bells of St. Mary’s,” “Spellbound” and “Saratoga Trunk” made thirty million dollars.

And it was that year that Ingrid Bergman first asked for a divorce.

She turned the pages more slowly. There were few pictures of Peter now. Cold, dictatorial, unresponsive, he added a steam bath to their house and made no effort to enter his wife’s world.

She remembered the evening she and some friends were discussing movies, and the name of MacArthur was brought up.

“Ah . . .” Peter had said. “General Douglas MacArthur . . . but what does he have to do with films?”

“No . . .” she had answered. “Charlie MacArthur, a wri . . .”

“I’m sorry,” he had interrupted her. “But I should have known you meant the wooden dummy with Edgar Bergen.”

When she tried to explain that Charlie MacArthur was a playwright and husband of actress Helen Hayes, he had gotten angry and flustered and left the room. (Whenever possible, she tried to put his world before her own, but he was never even to try to become interested in her life.)

By the middle of 1946, three years before she met Roberto Rossellini, she had already asked Peter for a divorce. He had refused. She asked again. He refused again. By the time her chance for escape came, she was ready to grab at it with both hands.

She closed the album and hesitated for a moment. Was she waiting for the telephone to ring or for a key to turn in the lock of the door? She was not sure. But she could only hear the Mediterranean lapping at the shore.

She did not open the albums again. She sat back in the red chair and closed her eyes and remembered each separate page and let the pictures flash through her mind.

STROMBOLI—1949

The smell of garlic in the peasant hut in which she lived. Oil lamps and candles. Tallow dripping onto her pillow. The slender young boy who came each morning with a pitcher of water so she could wash her face. Spaghetti served on broken plates and how good it tasted. The ache in her side after a day of scrambling up the volcano. Falling once and cutting herself on the sharp, black rock and Rossellini’s desire for realism, his delight as he used that scene with real blood on her leg and real pain at the corners of her mouth. And then his hand reaching for her and pulling her up. His warmth. The wonderful feeling—for perhaps the first time in her life?—of not feeling shy or awkward or lonely. The letter begging Peter for a divorce. Peter’s refusal.

ROME—1950

The months of being a prisoner in her apartment while reporters and photographers sniffed around the doors like hungry dogs. She had walked for pleasure. The agony of being cooped up, hemmed in to three rooms. The endless pacing. Waiting for the birth of her child and wondering what sort of man would keep her tied to him. Was it love that Peter felt or was it hatred? Was it his wife that he wanted or revenge? Whatever he had wanted, it was revenge that he got. His agreement to let her get a Mexican divorce came too late to save her pride.

February 3, 1950. Doubled up with pain, she slipped through the kitchen door of the Villa Margherita nursing home. The smell of fresh bread in the kitchen and then more pain.

Robertino. Waking two hours after her son’s birth to hear reporters and photographers spill down the hall and kick at the door of her room. The black-robed nuns fending them off until the police arrived. The shades that had to be kept closed because of the telescopic camera aimed at her window from the roof of the building next door. Pressing her nose to the shuttered window for a taste of fresh air.

The good things. The feeling of peace when Roberto was there. Robertino full and sleepy and curled like a kitten. The traditional ceremony of the nuns hanging up a ribbon—a white satin ribbon in the center of a blue field—to signify the birth of a boy. Roberto telling the world that Robertino was his son and that no one would take the baby away.

Then, the climax to it all. On May 24, 1950, their marriage by proxy in Mexico. She had waited in Roberto’s apartment, wearing a white dinner gown. When the news of their marriage was telephoned to them, they had toasted each other with champagne. Then, giggling because of the—or the happiness, she had said:

“Now we are legally tied for better or worse until death do us part.”

There was a sudden noise like the scratching of a key at a lock, and it was again seven years later—1957—and the memories faded back into the albums where they belonged. She turned towards the door, but the handle did not move, and the noise was only the sound of the wind tugging at the eaves.

She stood up and slid open the door to the terrace. Unlike the house, the terrace was neither dark nor calm. Splashed by restless moonlight, it hung suspended over the Mediterranean. There was a feeling of change in the air. The wind would blow from a different direction tomorrow.

Would it bring him with it? And if he did not return of his own free will, could she hold him? In holding him against his will, would she not be doing to him what Peter had done to her?

There was no answer except the barking of a dog baying at some sudden frightening shadow across the moon.

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE OCTOBER 1957