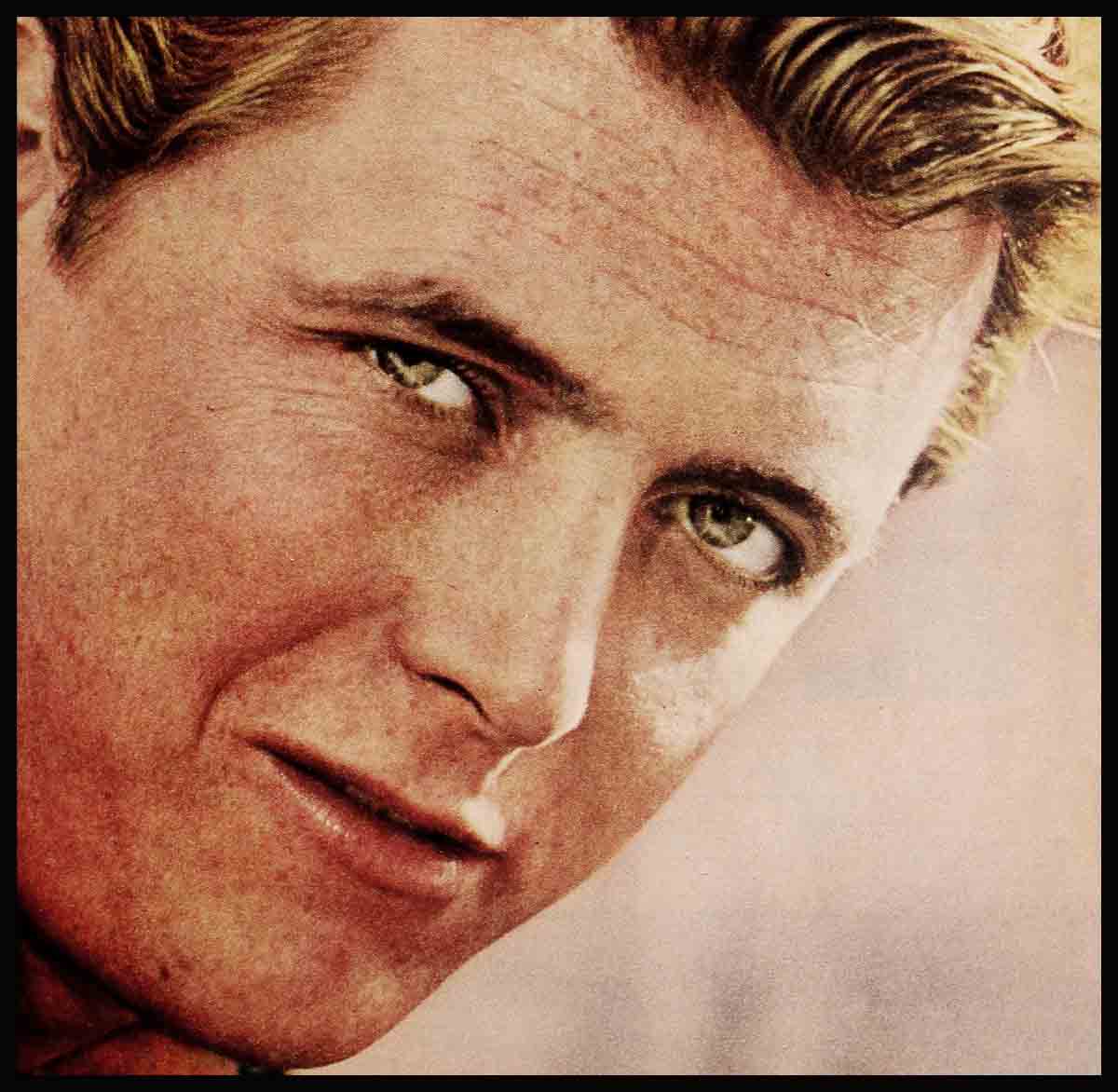

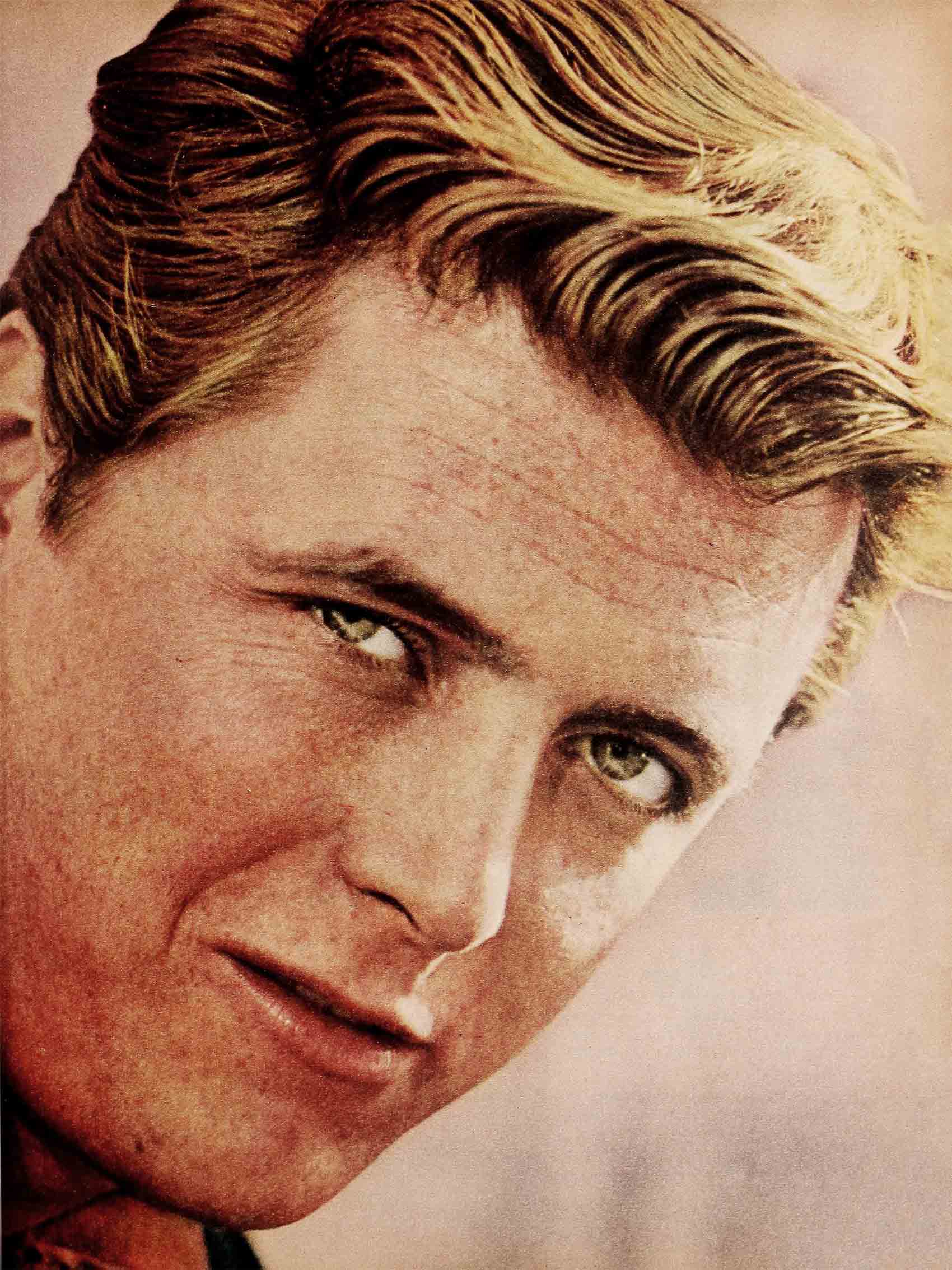

Slum Kid—Edd Byrnes

We lived in the heart—no, the guts—of the slums in a cold-water walk-up pad on East 78th Street in New York. The hallway of the six-story building had big holes in it, and the kids were always chipping away at the plaster. Or they’d write four-letter words on the walls. Sometimes a stray cat or dog would huddle in a corner and stink up the place with urine.

I lived with my younger brother Vincent and my mom. My sister, Joanne, wasn’t born then. My dad was a staff sergeant in this man’s Army, and he was never home.

Vin and I never got to know him too well. Sure, he’d get a three-day pass or a furlough, but all he did when he came to stay was drink. Now don’t get me wrong. I’m not knocking him. But facts are facts. He liked his booze, and he spent all of his money on it. That left very little loot for us.

Mom had to take odd jobs in defense plants to see us through those ‘hot dogs and baked beans’ days. And me, if I wanted Coke or candy change, I’d hop on Sunny Boy Tony’s rattletrap truck after school and help him on his rounds, hauling ice, delivering it to the neighboring saloons. Everyone called him Sunny Boy because he came from Sicily where, his mom said, ‘. . . the sun, it shines all the time.’ Or, if I wanted two bits for the movies, I’d play hookey from school and joyride with the ice truck all afternoon.

Those were the days when I roamed the streets like an alley cat, or I’d loaf in department stores where I’d look at chemistry sets. I was thinking seriously about being a chemist. I was twelve or thirteen then, and I had read a comic book about a chemist who saved the world from destruction.

And out of her pinchings and scrapings, my mom bought me a set for Christmas.

When she gave it to me that cold Christmas morning, I just couldn’t believe my good luck. I was so excited I started shouting and jumping up and down.

Dad had come home on a holiday pass, and he was still in bed. He wanted to know what in the world all the hollering was about.

I ran into the bedroom and showed him my chemistry set. How much did it cost, he wanted to know.

“Mom got it for me,” I told him.

“But how much did she pay?” he grumbled.

I said I didn’t know.

He leaped out of bed and began shaking his fists about ‘wasting money.’

Then he grabbed my mother and chewed her out for spending five bucks on such Junk. “Why didn’t you buy the kid a jacket or a pair of shoes?” he shouted at her.

She stayed calm. She told him it was Christmas, and she wanted me to have what I wanted. But he continued to rage at her. Then he stormed out to tour the neighborhood bars. When he came back at the end of the day, he saw me playing with the chemistry set. He took it all, the thin glass test tubes, the colored powders and the piles of litmus paper, and—yelling at the top of his lungs about what fools we were to waste money—he tossed the whole kit out the window, and I heard all my test tubes and bottles shattering on the sidewalk.

I wanted to cry, but I fought with myself to hold back the tears. Later that night, when I went to bed, I bawled like a baby. I hated him for doing that, hated him more than I like to admit. . . .

None of us really understood

Now that I’m older I realize something was eating away at him, something troubled him; otherwise he’d never have gotten drunk the way he did. He’s dead now. But while he lived, none of us really understood him.

But, then, in the slums there isn’t time to understand people. Everybody spends their time worrying about their next buck. Everyone’s so worried about how they’re going to feed their families from day to day that they take it out on each other—and on the kids along the block. Once, on a hot summer day, when I was playing ball in the street with a bunch of neighborhood guys, our ball bounced over against one of the tenement windows. It didn’t break anything; but a big fat man, a mill worker, came out in his undershirt and overalls and grabbed me, even though I wasn’t the one who threw the ball. He shook me up and down and told me never to do that again. He got so angry he ripped my St. Christopher medal off my neck.

So you learn to expect anything, and yet you expect nothing—if you dig me. After a while you learn to play it cool. Nothing matters. If you want to play stickball and a cop chases you, you make a face at him and laugh and run!

I’ll tell you what saved me. Movies. And girls! Not my first date, though. Man, that turned out to be an A-bomb. Though in a way it was that first bad experience that got me started on my career.

For three weeks I had stashed away my ice-truck money to take Angie out. She was in the same school with me and one day in history class I wrote her a note and asked her if she wanted to go to the movies with me on Saturday night.

She didn’t send me an answer right way, and I figured she didn’t want to go. She was poor, too; but not as poor as we were. Nobody, Daddy-O, was as poor as that! So, just about when I was giving up hope at the end of the day because she never answered my note, she came up to me and said, “Okay, Edd, I’ll go out with you. But don’t pick me up at home. Meet me at the drug store.”

I had saved two bucks. And, man, they felt like a million, and I wanted to spend it all on her. I had known Angie for some time. Her hair was dark blonde and curly, and she had greenish-blue eyes like mine. She always dressed in ruffled dresses with wide skirts.

I was flying high

Well, the night of the date came, and I got all decked out in my white shirt and blue tie, dark pants—the one pair I had that wasn’t ragged or too small—and sports jacket. It was spring, and there were warm breezes in the air, and my heart—well, it was flying high.

I had told my mom I was taking Angie out, and she was even more excited than I was. She wanted me to look good, and she pressed my pants for me so they’d have a clean crease.

She even slipped me a quarter.

I met Angie at the drug store, and she was dressed in a frilly white blouse and pink skirt, and she had a pretty pink jacket thrown over her shoulders.

I asked her if she wanted to see The Bad and the Beautiful at the Loew’s on 72nd Street.

“Sure,” she said. “But I’d like to have a Coke first. I’m thirsty.”

We sat down in a booth, and I ordered two Cokes. I asked her if she’d told her mom and dad about our date.

“No,” she said. “I decided against it. They wouldn’t understand.”

“But, gee,” I said. “You should have told them. I’ll bring you back early.”

“It’s . . . it’s not that,” she said. “It’s . . . it’s just that I didn’t want to tell them anything.”

I wondered why.

Then she added, “Oh, it’s too messy to explain. Let’s forget it. . . .”

I paid for the Cokes with the quarter Mom gave me. Then we walked to the Loew’s. The April air was fresh and breezy, and I felt like a king. I may have been the poorest boy on the block, but when there’s a sweet-looking girl by a fellow’s side, he’s prouder than a Rockefeller.

We saw The Bad and the Beautiful and it broke me up. To this day, it’s my favorite movie. I’ve seen it over ten times. I love movies about Hollywood and what goes on behind the scenes. Kirk Douglas’ acting moved me so much that he’s been my favorite actor ever since.

I had fo tell her

After the movie, I suggested we have another Coke, but Angie said she wanted a banana split.

Well, the movie cost ninety cents for each of us, and the drugstore Cokes we drank before the movie cost twenty cents. Subtract that from $2.25, and it leaves two bits.

I tried to sound matter-of-fact. “Gee, Angie, why don’t we just take a little walk? It’s a nice night. And it’s not late.”

“I’m not in the mood for walking,” she said. “I’d love something to eat.”

I didn’t know what to do. We passed a brightly-lighted luncheonette, and she looked at me, waiting for me to ask her to go in.

I didn’t.

At the end of the next block, we passed a Palace of Sweets. She was the one who spoke up. “Let’s go in here,” she said. “They make the best banana splits. And they have homemade peanut clusters!”

I fumbled for a minute, then I decided I had to tell her. What else could I do?

“Angie,” I began, feeling the blood rush to my face as I lowered my voice to a whisper from embarrassment, “I . . . I don’t have enough money.”

She didn’t hear me. “What?” she said.

I had to tell her again.

She looked at me for a minute without saying anything. Then, she said, “I think I ought to go home.”

I walked her home, and neither of us said a word. As we walked I couldn’t think of anything to say, and Angie—well, I guess she wasn’t talking to me. As we walked, I watched our shadows that the streetlights cast on the sidewalks. I couldn’t look at her. I wished I were a shadow without all these troubles. She was right, I had no business asking a girl out if I couldn’t even treat her to a sundae or a banana split. . . .

When I brought her to the door of her building, she said, “That’s what I didn’t want to tell you before . . . in the drugstore. I didn’t tell anybody, not even my mom and dad, I was going out with you because I didn’t want them to know I was dating the poorest boy in school!”

Was it too much to ask?

She turned and ran inside. I was so upset I couldn’t swallow. I gagged on her words.

I walked away, toward the Fast River where the April winds carried the salty scent of the sea along the city streets, and I walked and walked along the waterfront for what seemed like miles.

What was I going to do with my life? Were we going to be poor forever?

I wasn’t asking much out of life. But, man, a warm pad, at least, in a clean building, some decent food once in a while, enjoying a Coke and a movie without having to save up for it, an easier life for my mom . . . was that too much to ask? I knew nobody was going to reach out and hand me a sou on a silver tray. Id make my way myself. I’d be an actor, I decided. And I’d work hard, study hard, till I made it.

First thing I’d have to do was go back and see that movie. See how Kirk Douglas made that part come alive so. I’d learn from him. I’d have to get some money in a hurry and get started on my training course, so the next day I went to see Sunny Boy Tony. I asked him for a buck in advance. I’d work it out next week, I told him. With that dollar I went back to the movies and saw The Bad and the Beautiful again. From then on, every time I had money in my pocket, I went to the movies. I studied the actors.

But that day when I went over to Sunny Boy Tony’s place, something happened to make me more determined than ever. Tony was a guy who always had a smile and a pat on the back for everybody. And this kind of treatment was new to me. He introduced me to his whole family, to his wife and his mother and father and all his kids.

They asked me to sit down Aad have something to eat with them. I never really had enough to eat so I sure wanted to. But I didn’t know if they were just being polite.

To play it safe, I said no, I couldn’t.

But they all shouted, “No, no, you sit down with us!”

Somebody turned on the radio—I think it was Tony’s mom—to an Italian radio program, and we listened to some jumpy Amapola-like music while Tony’s wife fixed the feast in the kitchen.

A real home

Then, we all sat down and ate antipasto and spaghetti and some apples with cheese. We all drank red wine that Sunny Boy Tony poured for us from a big gallon jug.

Then, Tony’s small and wrinkled mom took me aside and she showed me all the picture postcards she had saved from the old country.

I liked their apartment. It was small like ours, but it was brighter. There were religious paintings on the walls and artificial flowers on the mantelpiece and there were fancy lace curtains in the front room.

I played with Sunny Boy Tony’s kids for a while and then I went to the movies.

When I went home that day, I told my mom about Sunny Boy Tony and his family. “They’re so happy,” I told her.

I realized too late I never should have said that. Mom tried so hard. It wasn’t her fault we didn’t have a happy home. She looked at me, and her eyes filled with tears. She started to talk, but then she broke down and sobbed, and I went over to her and put my arm around her and said, “Don’t cry, Mom.” But she couldn’t stop. “You wait and see. I’m going to work hard, and everything’s going to be all right.”

And I meant it. I wouldn’t let her down . . .

I got a job in a defense plant in Long Island. Every day when I worked in that assembly line, doing the ‘same thing, hour after dragging hour, I dreamed about the promise, dreamed about the future. During the lunch hour, I’d go to the locker room and eat my sandwich while I studied the movie magazines. I was getting to be quite an authority on films and actors—especially on how they got their start. I began thinking about California, and one Sunday when I went to visit Tony and his family, I told him I was going to hitchhike out West.

“Ah,” Tony’s mom said in her broken dialect, “Is where the sun shines all the time . . . ?”

The sun really does shine

So I left New York and came out to dreamsville where—she was right—the sun shines most of the time. Sure, it took a while to get started. The slums had taught me that nothing comes easy in this crazy-man-crazy world.

Besides, I promised my mom Id look after her. So I took whatever odd jobs I could find to earn enough money to send home. To this day I mail part of my paycheck to Mom and Sis in New York so they can live comfortably. My brother Vincent’s in college on a scholarship, studying to be a teacher.

And me? Well, I’m making up now for all the things I missed when I was a teenager in the slums of New York. The pad I’ve got is big and clean and bright, with a balcony overlooking the Pacific Ocean and this sunshine town. I’ve got a barbecue pit and I can charcoal-broil steaks three times a day if I feel like making up for those hot-dogs-and-baked-beans days. I go out for sports now I never had the time or the money for: waterskiing, tumbling, and driving at a fast clip in my white Thunderbird. I’ve got a good collection of popular and classical ballads. I look over my wardrobe today, all those suits and slacks and sports jackets, and I can’t help remembering that day my mom tried to make my one decent pair of pants look new for that date with Angie.

The girls in my life now? Man, there are plenty of them, and none of them like that chick. No one special yet, though. Before I settle down, I just want to enjoy these things I dreamed about back when I was a slum kid. . . .

THE END

Watch for Edd in Warner Brothers’ UP PERISCOPE.

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE MAY 1959