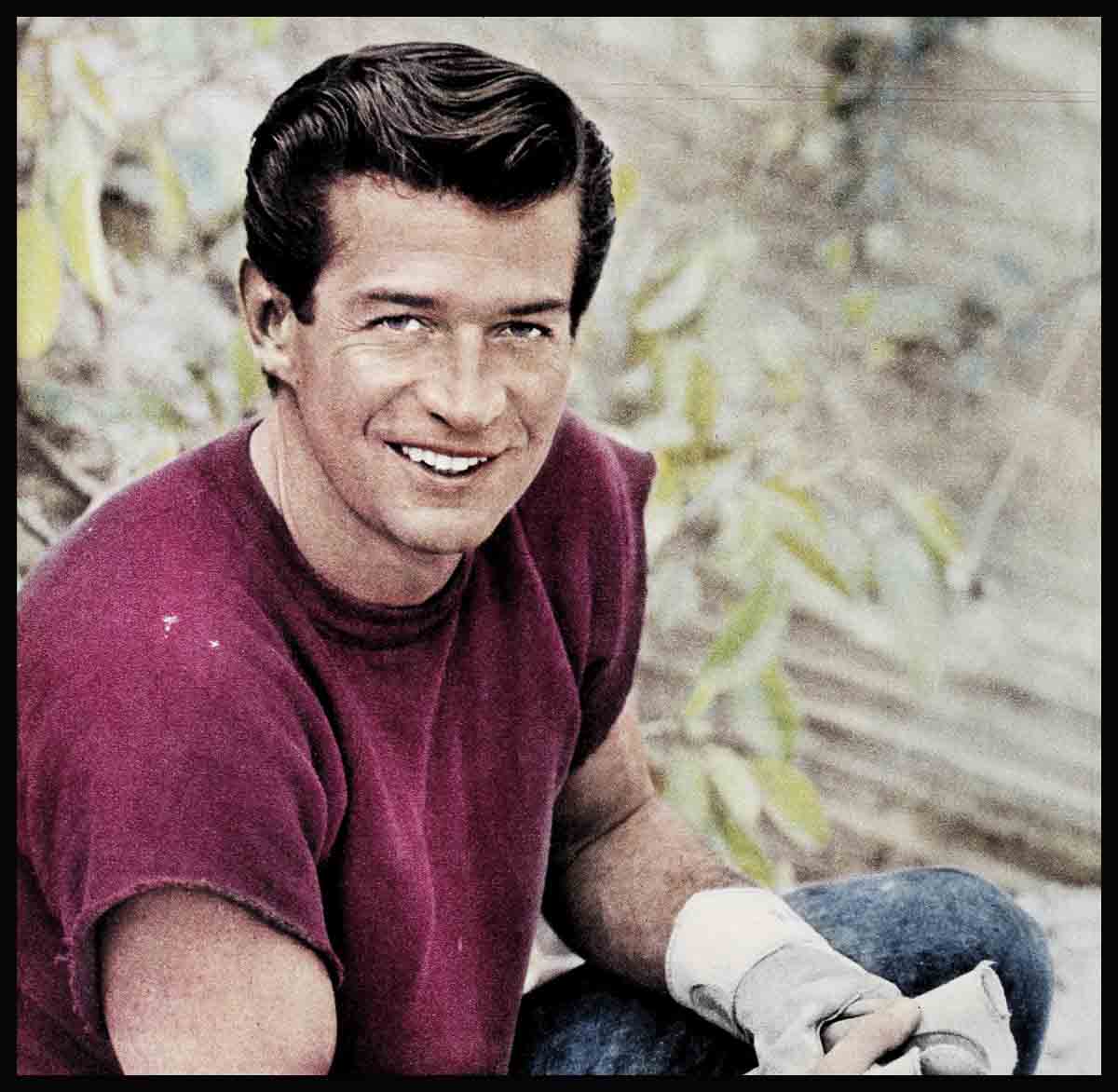

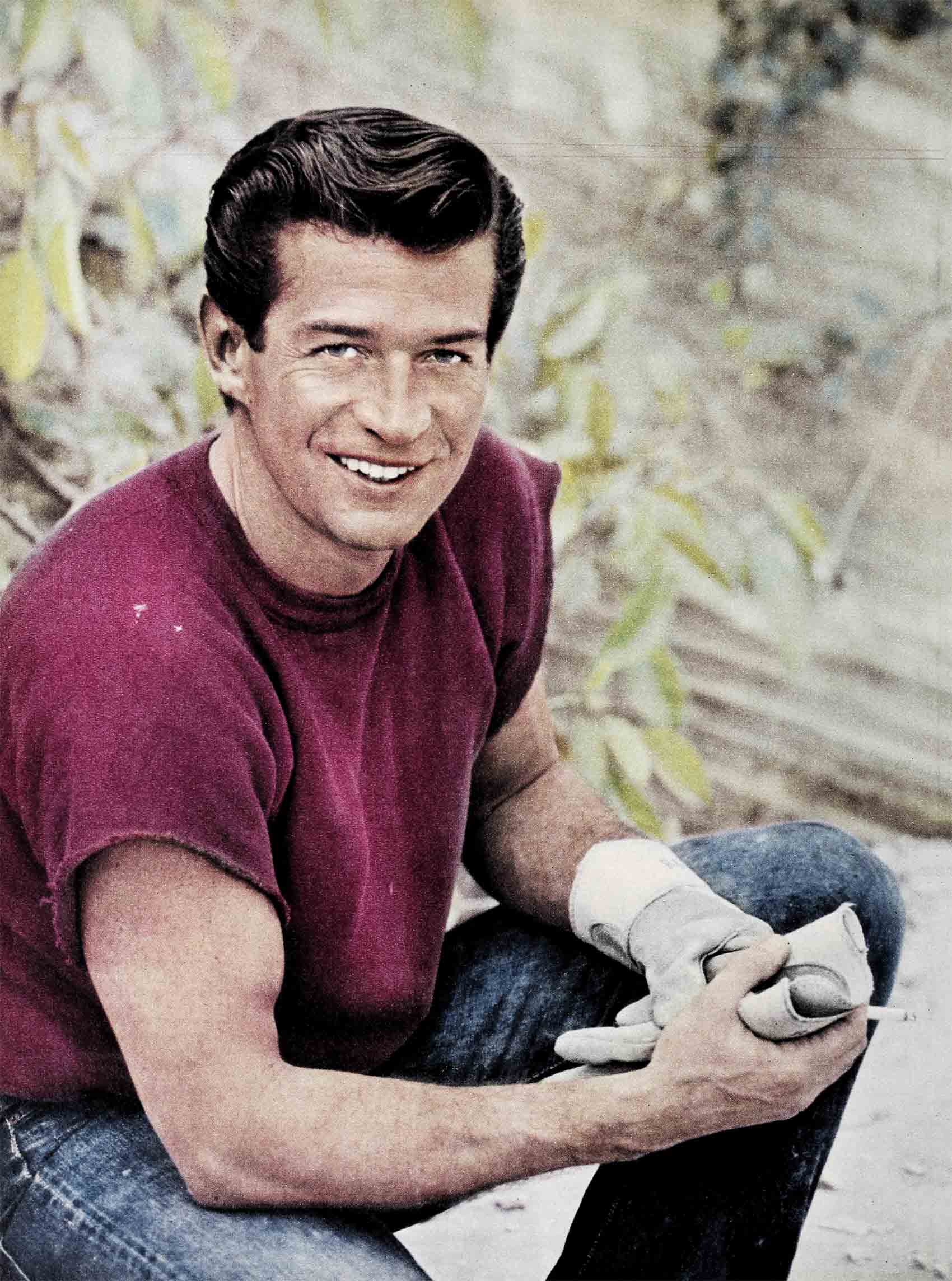

My First And Last Words On George Nader

Editor’s Note: George Nader’s father has always turned down requests for stories about his son. George explains, “My parents have no desire to capitalize on my Hollywood connections. They’ve developed a great interest in my work, but they’d be just as happy if I became a banker or a plumber. But my father is the person who knows me best, so I’ll ask him this favor, just this once.”

The other day, while reorganizing some family storage space (my wife’s polite way of saying, “Clean out the garage!”) I came across a battered old dust-covered packing box. Among other things, it contained ten model planes and trains, some carved wooden arms and legs for puppets, several baseball bats and moldly-looking mitts, two stamp collections, a group of dogs and horses modeled in clay, marbles and more marbles, three skull caps with bottle tops riveted on them and a rock collection with a sprinkling of dried lizards!

Memories are made of such stuff as this, and that garage incident was a reminder that time and maturity have wrought many changes for my son, George Nader, Jr. Today he is the man we visualized when we inherited the responsibilities of parenthood—meaning the care and concern that he’d have to survive when put on his own without discrediting himself. We tried to raise a gentleman. We think we did.

Until his college plays we never expected George to be an actor. I don’t think he planned on it. He was more interested in writing short stories, and I still wish that at least one story could have been printed for the public. Looking back, I suppose there was an early indication that George was destined to act. I remember an incident when he was about three. We had gone on a family picnic and returned home, happy but exhausted.

His mother finally succeeded in getting George through the business of his nightly bath. But when it came time for us to hear his prayers, he was obviously bored with the same old routine and came up with a new twist. By drawing his lip back over his teeth, he created an illusion of a toothless old man and piously recited, “Now I lay me down to sleep!” An act like this sprung at the end of a pretty hectic day was too much. Before we burst with laughter—we hurriedly left the room!

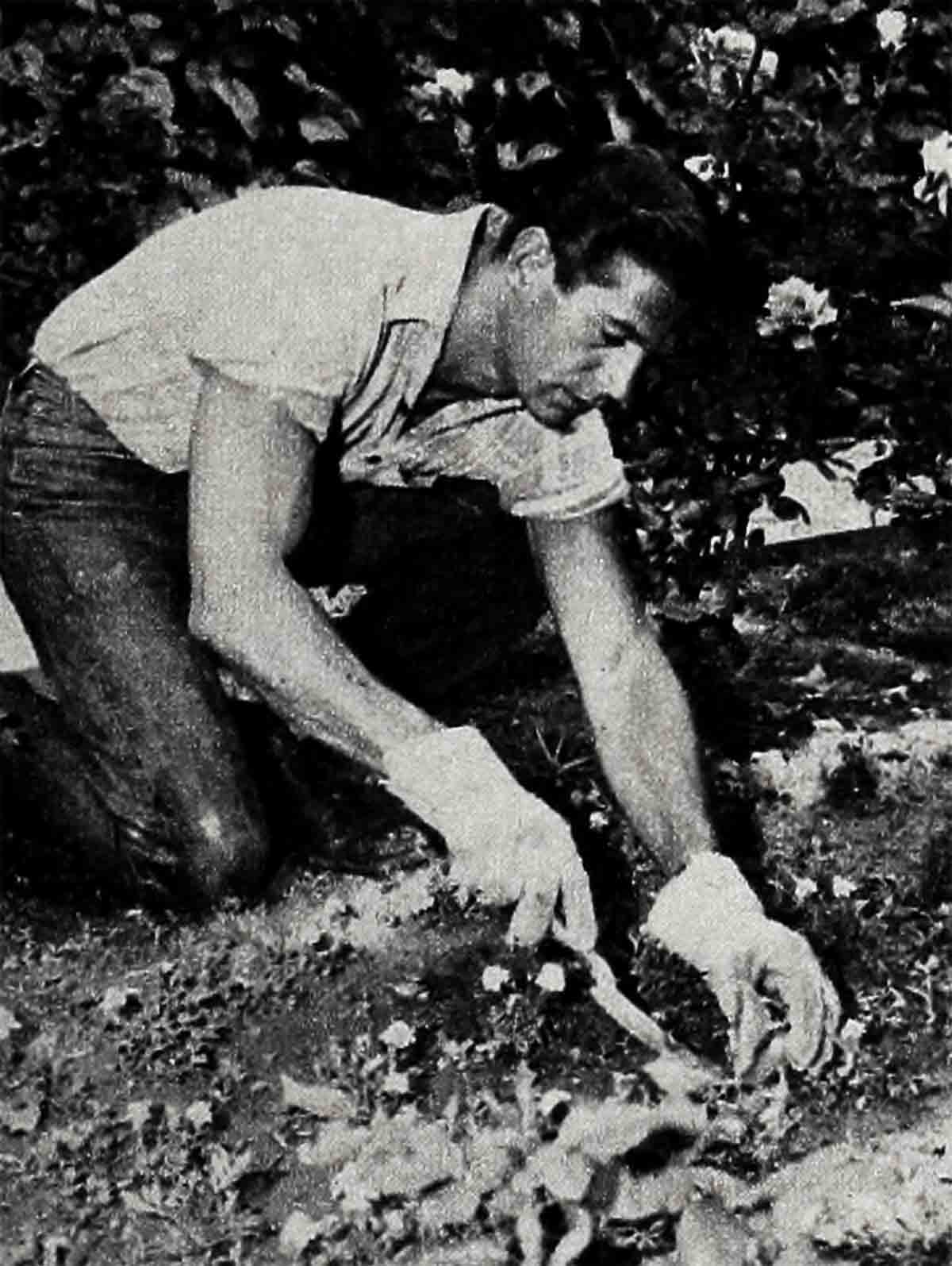

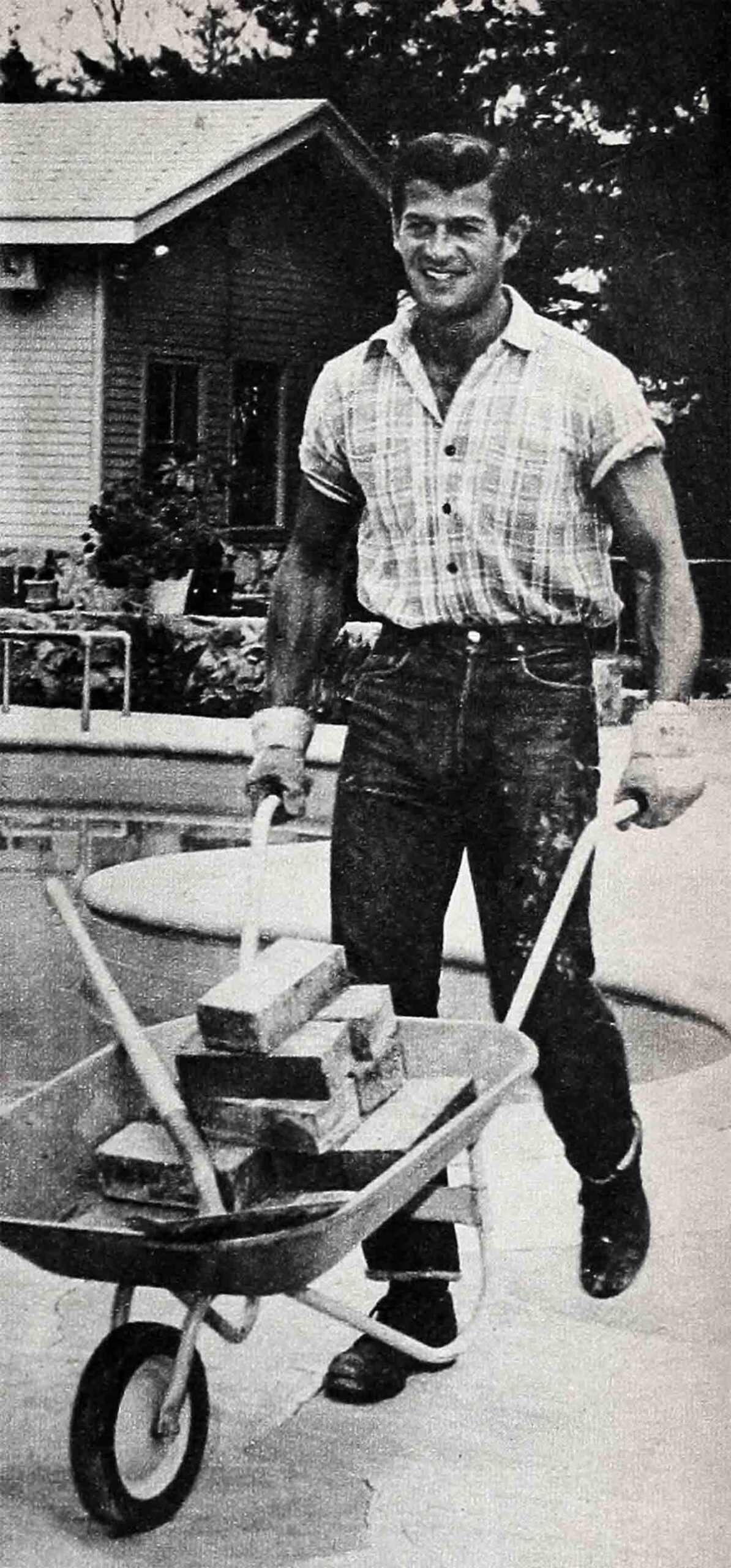

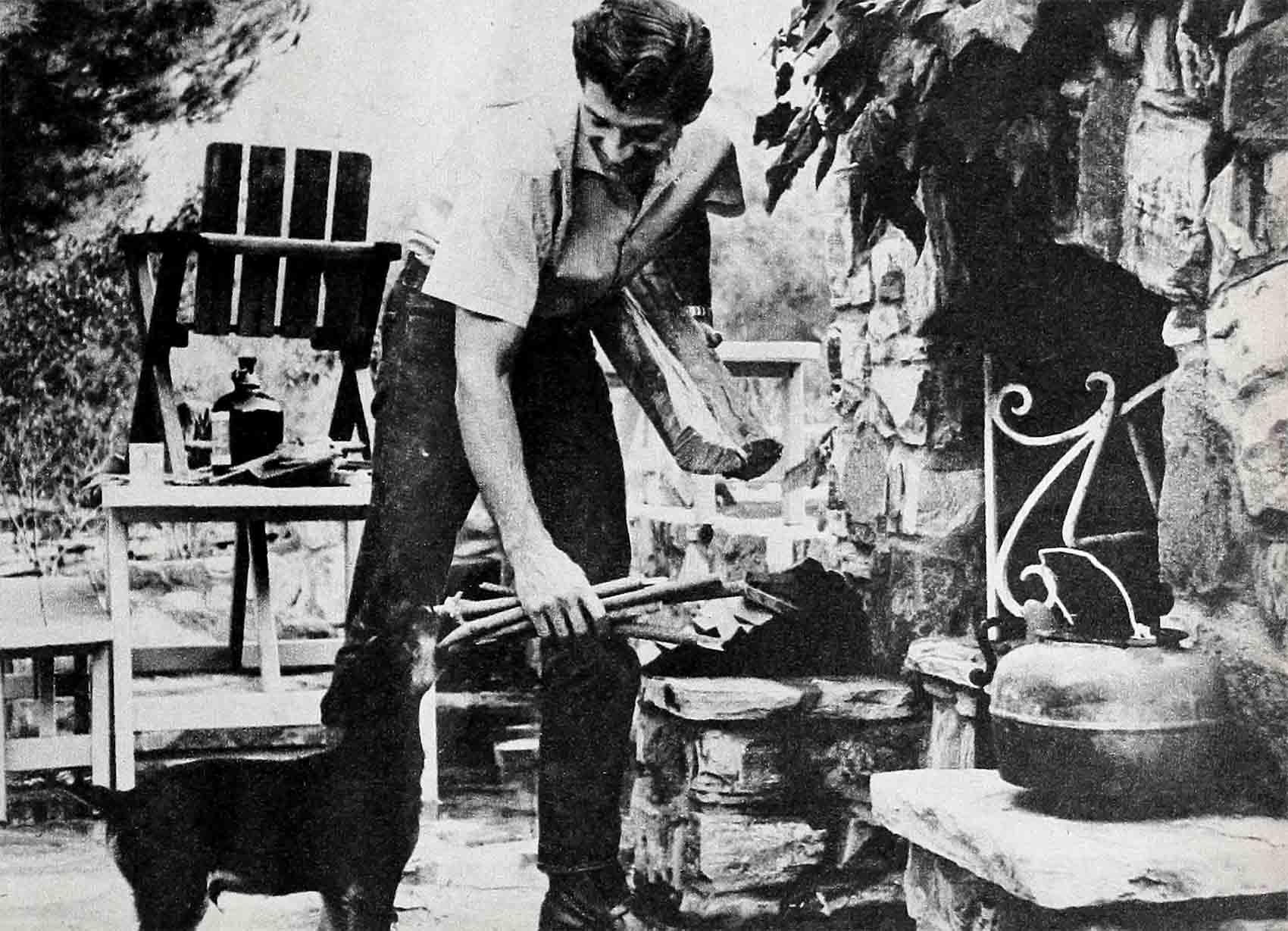

This last Easter, George invited sixteen members of our large family over to his new house in Sherman Oaks. During the conversation one of his aunts remarked: “It doesn’t amaze me so much that George has become an actor—it amazes me that he lived to become an actor!” This started us all recalling the different children in the family and the scrapes they’d gotten into. George outdid them all in the childhood art of “living dangerously.”

From the beginning, instead of walking he always ran. It’s still a characteristic today, which accounts for his going after and getting anything he needs and wants. I recall a Sunday at his grandmother’s house when dinner was announced. George was playing tag with his cousins. The playing ended abruptly when he did a sensational but unscheduled skid and nosedive from a stair landing—smack into the very center of the dining room table! Although his mother began as the type who faints at the sight of blood, she ended up more expert at bandages than the average doctor or nurse.

Being an only child, George had to be kept busy to stay out of trouble, we realized. So we tried to give him every advantage we could afford. When we found he liked the piano, he took piano lessons, and with coaxing he will still sit down and play a duet with his mother. George took to making puppets in grammar school; he liked chemistry in high school; so we bought him a chemistry set. Later on, when he became interested in photography, we managed a darkroom and equipment so that he could pursue this hobby to his heart’s content.

If we made a promise, we always fulfilled that promise. As a result, George always knew where he stood. Parents have to be careful never to break a promise, because this mistake is heartbreaking to a child. George never had to surmount domestic problems. Our home was always open day and night for his friends, and there were snacks in the icebox and bottles of pop. We treated our son like an adult from the time he could reason. At high-school age he was given his own latchkey, so that he could come and go as he pleased. By putting him on his own, we believed he’d survive if he got into scrapes. If he did, we never knew, because he never came home running. We still wouldn’t know, because George has his own quiet but forceful way of working things out. He refuses to burden or bore others with what concerns him.

It always pleases us when people comment on George’s adaptability and his easy manner with everyone, including strangers. This served him well during his stretch in the Navy. For an actor especially, it’s a most important asset. George has always liked to share with others. While we were glad he was growing up with what you might call “a highly developed social instinct,” there were times when he carried it a bit too far.

‘Times like playing in a muddy creek with friends, then bringing them all into the house all dripping with mud and insisting upon them using his mother’s dainty guest towels. Other times when he emptied the contents of his piggy bank, to treat the neighborhood kids of all ages at the candy store. At moments like this, his mother and I were left with the vague feeling that we hadn’t quite gotten the message of thrift, as such, over to him!

Although George was an actor eight years before he signed with UniversalInternational, he has never been driven by impatience or frustration. As a result, he’s been able to keep a sane perspective, and the coordination of his maturity is beginning to pay off today. Maybe it’s taken a little longer, but he can play any role within his physical limitations and be thoroughly convincing, too. George knows this, but he is not conceited. He is self-confident, and that’s quite different. It’s very heartwarming to witness the faith he has in his own future, and his enthusiasm about his current work in “Flood Tide” and “The Female Animal.”

It’s true that we’ve lived here for many years, but we’ve never had any curiosity about Hollywood. Naturally we’d be there in a flash if George needed us, but until we visited the “Joe Butterfly” set recently, we had never set foot on a sound stage or lunched in the studio commissary. I don’t believe, therefore, that I am qualified to judge any actor but my own son.

But I would like, if I may, to venture an opinion. Those actors who bid for attention with unorthodox dress and defiant attitude must be devoid of humor. We’ve always tried to have a sense of humor about life and look on the positive side of things. Both my wife and I feel that dwelling on gloom, misfortune or past unhappiness is merely time wasted. Throughout the years I’ve been happy to see that George thinks along these lines, and I know it’s saved him from much unnecessary anguish. With the many pressures of his career, it helps to be able to look on the bright side.

There was a time, for example, when my wife was to have a very serious operation. George was living at the beach, a spot where he developed his love for swimming, which was the chief means of building up his muscular body. He was extremely tanned and bleached to a towhead by the sun and salt water. In his haste to get to the hospital, he didn’t stop to shave, he wore faded dungarees and a red and orange striped beach shirt. His mother made mild comment.

The second morning following the operation, George appeared at the hospital impeccably dressed in his new tuxedo. He held a bunch of flowers under one arm and a box of candy under the other. At sight of him his mother’s near hysterical laughter made the nurse throw him out immediately. When she was out of danger and a little stronger, my wife said to me: “That visit from George was better than any medicine. His wonderful humor made me feel that all was right with the world again!”

I could recite endless incidents when George chose to apply humor instead of rancor. Although we were far from rich, it wasn’t necessary for George to work his way through college. We saved for that. But my theory was that he should work for extras, like his first car when he was a freshman at Occidental. He clerked in a grocery store to pay for it. Then there was that time he got a job at Bullock’s, to earn money for Christmas presents.

There were and are two things that bore George. Mathematics—and wearing hats. From the beginning he almost refused to learn anything about Math, and, like most younger Californians, he wouldn’t be caught dead in a hat. Bullock’s regulations insisted that all sales persons must wear head gear. With his God-given aptitude for accepting that which cannot be changed, George merely borrowed my very formal-looking Homburg—which was a couple of sizes too small for him! With a twinkle in his eyes, he would gravely place it on top of his head just before entering and leaving the store.

Generally speaking, George may give the impression of being a passive person. But he’s capable of kicking up a storm after weighing the issue against the results and deciding whether a fight would be worthwhile. After he had enlisted in the Navy, they allowed him to graduate from college. Then they gave him another year of communications training at Harvard and he went right into active service from there. I never heard him complain, because it was his duty and expected of him. George has retained this same direct and realistic approach to anything he undertakes.

Naturally we would like to see George surrounded by his own family. The reasons are obvious. Besides, while he can do almost anything, he can’t darn socks! Seriously, knowing George as only a father can know a son, I know he’ll marry the right person at the right time. He’ll make a wonderful husband, too. Love of home is instilled in him deep. Simple things like good old-fashioned “sings” appeal to him; he enjoys canned soup as much as pheasant under glass; and his sense of responsibility has the strength of Gibraltar.

The first time we saw George in a picture, he was with Jeanne Crain in “Take Care of My Little Girl.” If anyone expected me to rave, they were mistaken. George didn’t have enough to do to rave about, but I am indeed proud of what I see up there on the screen today. You know, when he became an actor, George said he was going to keep his name. This was fine with me, except I wasn’t about to change mine! So I had to learn the hard way not to say, “This is George Nader” in making business calls. It always started a chain reaction.

I remember particularly well one incident of this kind that happened when I had a business appointment with a man at his home one day. When I walked into the living room, his teen-age daughter was standing at the phonograph, going over her record collection.

I said, “Hello. ’m George Nader.” Her head shot up, and she covered the distance between me and the phonograph in one bound, face flushed, eyes gleaming eagerly. Then she stopped short, looked me over, and drooped visibly.

“You must be mistaken,” she sighed disappointedly. “George Nader is a movie star!”

“I’m aware of that,” I answered. “Our names happen to be alike.”

“Oh,” she said. “Please sit down. My father will be here in a minute.” And with that, she went back to her records.

“By the way,” I asked casually, “how do you like the actor, George Nader?”

She straightened up, and rolled her eyes toward the ceiling. A dreamy, faraway look came over her face. For a moment, I wasn’t quite sure whether she’d heard me, or this was an entranced state caused by the latest calypso record.

Then she sighed deeply and breathed softly, “He’s the most!”

George’s old man got a great kick out of that, I can tell you.

THE END

—BY GEORGE NADER, SR.

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE AUGUST 1957

No Comments