The Fighting Story of Victor Mature

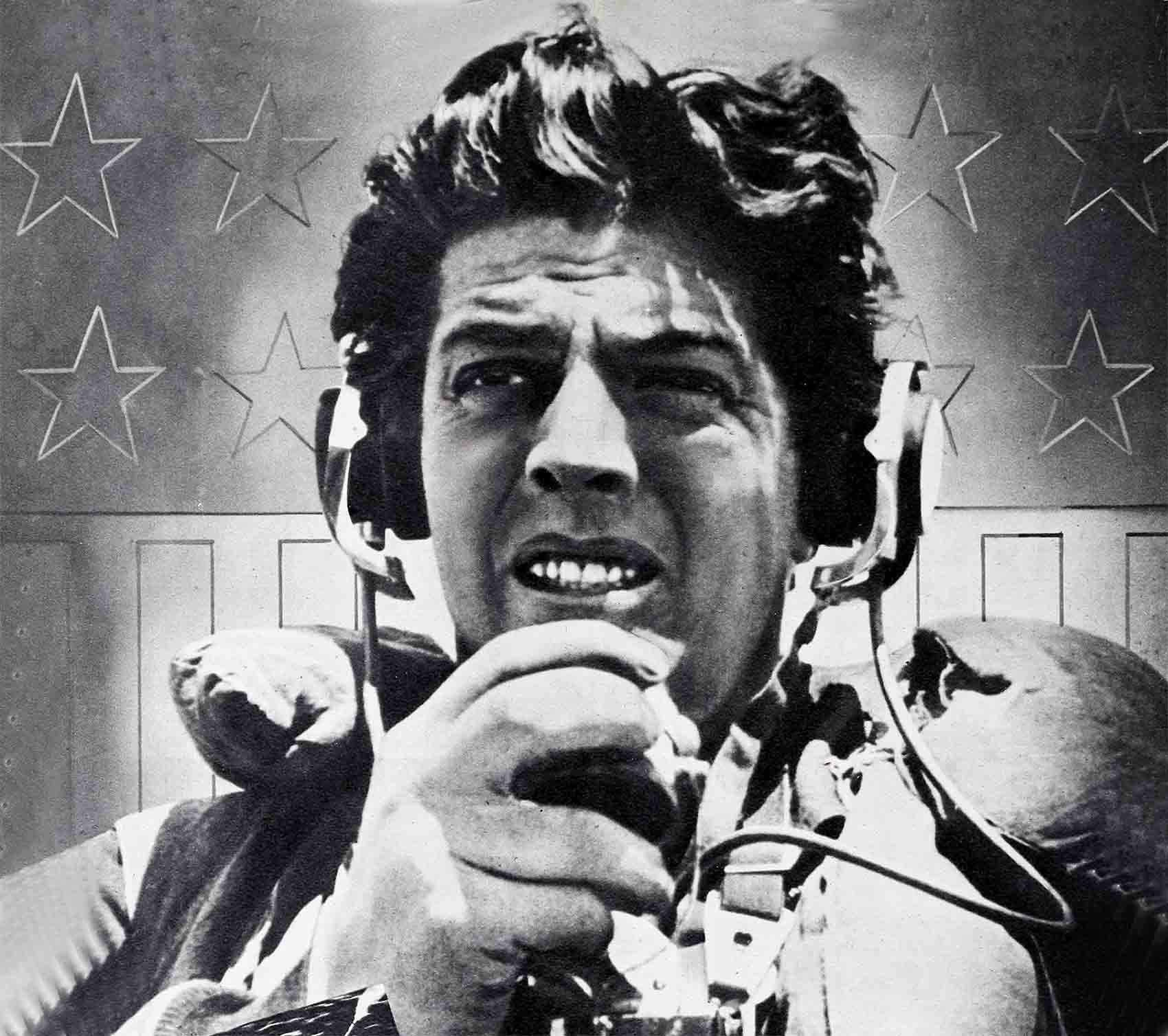

What happens to a man who has spent a year of his life cruising enemy waters, facing enemy fire? The same thing that has happened to Victor Mature—a tightening of the emotional fiber, a hardening of the nerve centers, the growth of sharp realism beneath an overlay of casualness.

No longer is he the brash Hollywood star of the colorful personality, the constant gags and the love of the limelight. These days under his hail-fellow-well-met exterior there is an undercurrent of grimness, a new intensity of purpose.

When Vic enlisted in the Coast Guard, he got boos and catcalls; boos from the crew on his ship because he was a star, catcalls from columnists who wouldn’t believe he was taking his service seriously. But aboard one of the more active cutters on North Atlantic convoy duty, Vic won his rating of Chief Boatswain’s Mate stripe by stripe, and the respect and friendship of his shipmates step by step.

Today he is a fighting man with a fighting story. Here is that story—in his own words. . . .

We were cruising off the coast of Greenland. I was sleeping in that morning. They permit you to sleep in mornings when you come off the twelve-to-four watch, as long as you’re up at eleven and ready to go on at twelve again.

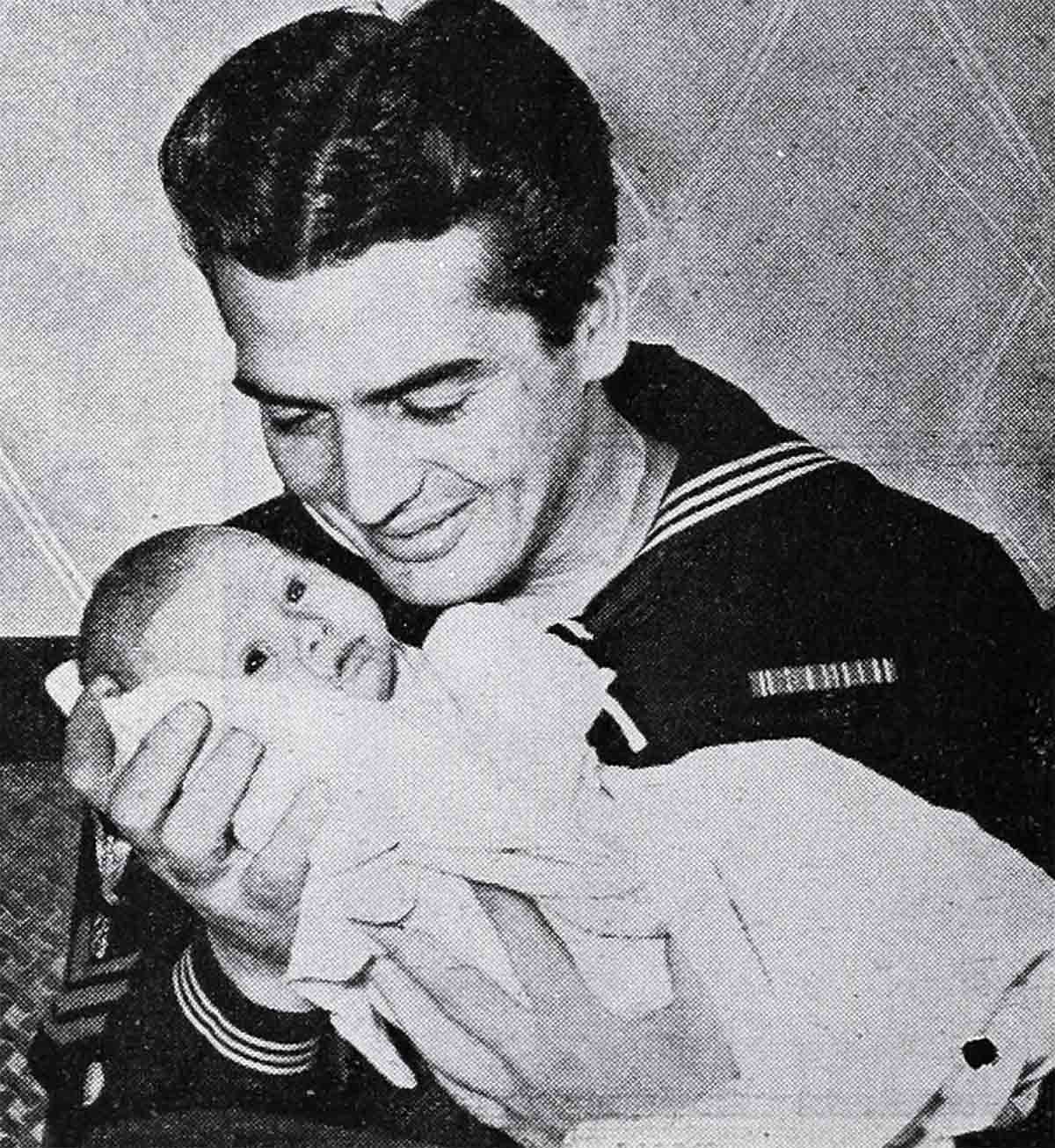

“Hunk,” Mazie called, “get up! You’re wanted in the Ship’s Office. You’re going back to the States, you lucky So and So!”

I turned over. “Go away!”

“On the level,” Mazie insisted. “A dispatch just came . . .”

“. . . from the President, no doubt!”

“May be! For all I know!” Mazie said. “Anyway, it says Boatswain’s Mate, Victor Mature, First Class, is to proceed at once to the Treasury Department, Third Naval District, New York City, to participate in the Third War Bond Drive.”

I sat up. That could be! “If you should be kidding!” I threatened that big Polack yeoman from Meadville, Pennsylvania. “If you should be kidding. . . .”

I had nicknamed him “Mazie” one day when I was inking my laundry and he had asked me to do a few pieces for him. A nickname was in order because he was a buddy and I could neither spell nor pronounce his real name. I had been given my nickname of “Hunk”—not to be confused with the Hollywood appellation “Hunk of Man” but short for “Hunk of Junk”—in the same indelible way.

Mazie wasn’t kidding. Within a few hours I was in the air. (You don’t need time to pack when you have a duffle bag. You just throw your stuff in. I made my bag myself. As a boatswain’s mate I had learned to work with canvas.)

I soon found myself staring down at the cold green water of the North Atlantic. I had sailed over it many times in many convoys. This was the first time I had flown over it. It looked flat from way up there. But I knew it wasn’t. It’s a tough sea, the North Atlantic. Year round its temperature varies only two degrees, ranging from thirty-two to thirty-four. You’ll never hear of any rescues like that of Rickenbacker and his buddies, for instance, up there. Four to eight minutes in that water and you’re a dead duck. This probably accounts for the fatalism that is so common among the kids who serve in convoys to Murmansk, Russia, and other northerly bases.

I remembered last winter . . . the way the lines stretched, day after day, from stem to bow . . . the way we would grab hold of those lines before we actually came out of a hatch. We rolled from forty-three to fifty-three degrees. We took off the lifeboats because—submerged most of the time—they were so thick with ice that they were useless. We had a gang chopping ice—four to six feet of it—off the ship every day. And their hair used to freeze while they were doing it. In bad weather eighty to ninety feet of water reared before us. We used to wrap our legs around stanchions and hold our bowls of chow between our knees. Weeks on end we slept with all our clothes on—and our life jackets too.

Brother, if you want to burn the kids in the Coast Guard just let them think you think they run around in itty-bitty boats guarding the coast.

I began to feel sorry for the fellows I had left behind. They had been swell about my leaving. But I knew they all could use a little time out too. In the past ten months we had had only four days in the States—while we laid up for repairs—and that hadn’t allowed most of them to get home. You’re not exactly scared when you go out in a convoy, it’s just that you never relax. You go around with your eyes popping, ready to laugh or yell at anything. Standing watch, for instance, is a strain. You may talk to the fellow beside you but you never look at him.

Suddenly I began to wonder what I was doing in that plane flying westward. I began to feel I belonged back on my ship, on duty with the rest of the crew. I didn’t think there was one thing I could say to you folks back home that would influence you to buy one more Bond—or one more Stamp for that matter—than you already intended to buy. Because I couldn’t tell you how tough war can be when you’re really in it—this being something every boy I knew wanted kept from you.

When I arrived at the Treasury Department in New York City I discovered I would not travel on the special War Bond Cavalcade Train with the Hollywood crowd but that I would go out alone.

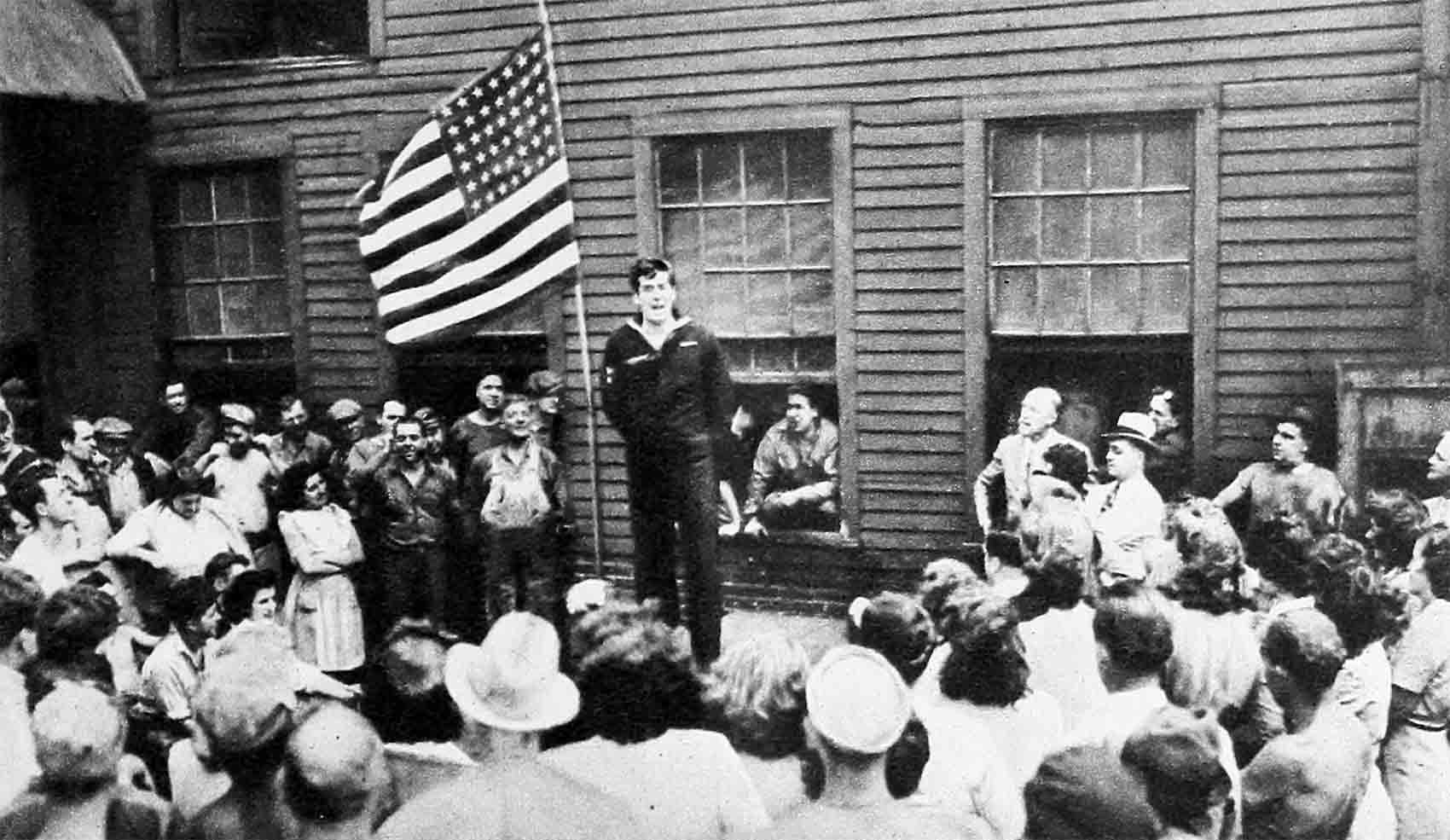

I talked at defense plants, department stores, theaters, and town rallies held in baseball parks, football stadiums and on street corners. I talked to four and five groups a day. Sometimes I kept right on talking in my sleep. At the Winchester Arms plant I talked to four thousand employees crowded into a street intersection. A trolley car ran through the middle of the crowd while I was talking but I’m darned if one of them missed a syllable.

They listened as intently as they did—I know, don’t tell me—not because I had been in movies but because, as a serviceman, I had an identification with some son or brother or husband or Big Moment who was in service too. Because it was possible I’d talked with that guy they loved or had seen him or had heard about him through someone else.

I didn’t tell how tough war can be . . . I talked, as I had planned coming over, about the lighter side of war, about things like mail time, for instance.

There’s a riot when mail call sounds. “Get a letter from her?” guys ask each other. “She still love you?” You don’t get away with saying yes, you got a letter and she loves you more than ever, if possible. You have to show the letter. You have to get it from the back of your pants—the only pocket a sailor has—and prove it’s a new letter by the postmark. Then—you can take time to fold it so no private message is exposed—you have to show the ending. If a letter ends “As Ever” or with any mild phrase like that do you take a ribbing! That’s why I told the girls always to put plenty of loving in the last line.

In Pittsburgh one evening a lovely lady came up to me. “I’m Mrs. Bukes,” she said. “My son, Ted, wrote about you.”

She had snapshots of Ted and I recognized him as one of the kids in our convoy, one of the kids who asked me to write to Hollywood for autographed pictures; of Betty Grable and Lana Turner and Hedy Lamarr mostly.

“How did Ted look when you saw him?” she asked.

Now that I had placed Ted as radio man on the Coast Guard cutter Escanaba I wanted to get away. I couldn’t tell whether or not she had heard from the Navy Department. I reasoned they might slip up once in a while.

The Escanaba was sunk June thirteenth. The explosion was terrific. She was cut in half and went down in nineteen seconds. Long after she sank you could feel the heat of her fires rising fathoms deep through that cold water. Only two boys were saved. Afterwards there are certain maneuvers which the other ships in the convoy must execute to form a patrol around the torpedoed area. Until this is done it isn’t safe to attempt any rescue. A ship making a rescue stands still, of course, and would be an easy target for a U-boat.

“Ted would be glad I’ve met you,” his mother said. Tears were falling down her cheeks by this time but she kept on talking quietly. I knew she knew.

I told her, then, I had seen Ted sixteen hours before the Escanaba was hit; that I’d given him pictures of some movie stars he had asked for just before we sailed.

“I have the pictures,” Mrs. Bukes said. “He must have mailed them home—for safe keeping—before he went aboard that night.”

She took a letter from her bag. “Ted sent me this letter last Christmas. When I heard you had come home to talk about War Bonds I thought you might like to read it.”

“Dear Mom,” Ted’s letter read,

“Tomorrow is December 7th. One year of war. It makes me feel proud to be part of the service when I see all around me what has been done in this past year. I’ve served in combat zones and I am ready to go back every time Uncle Sam wants me. I think next Christmas will be happier. I believe next year will bring success to our forces. I hope so. I am proud of all the boys in all of our services and I know that with boys like we have in America fighting for what is right we cannot fail.

“Although I am happy to be doing my part in this war what I really want is to do my best to see it gets over with soon—so I can come back home again. That’s what every fellow wants. And don’t worry. Mom, I will be back.

“But we must all do our share—and more. We all must remember Pearl Harbor. I only hope that the civilians, those who possibly can afford to, will keep buying War Bonds and Stamps so our boys will have the stuff to end the war more quickly and get home sooner. I cannot afford to buy a Bond with one payment, of course, but I am buying Stamps as are many soldiers, sailors, and Marines.

Love and kisses,

Ted.”

I asked Mrs. Bukes if I could copy part of Ted’s letter and read it to people. Because when I finished reading that letter I was through with concentrating on the light side of the war, believing the folks back home couldn’t take the strong stuff. Ted didn’t believe that; he gave it to his mother straight.

So here it is, all you people back there in that wonderful land behind the Statue of Liberty: Until a few months ago for us this war was just a preliminary skirmish. Only from Salerno on—where plenty of our kids died—have we been in on the real fight. It’s going to get worse, a lot worse—let’s not kid ourselves. But as Ted Bukes said to his mother, there’s only one way to get this war over and bring your boy home—and that’s by buying War Bonds and Stamps not only with the money you can spare but with the money you can’t spare—by buying Bonds and Stamps to a point of sacrifice.

Payroll deductions for War Bonds are fine. They go on week after week just the way the war goes on week after week. But if you have any other money—money you have put away for a rainy day, maybe—it is needed too. I’ve seen a little of this horrible mess and, believe me, it’s raining hard over there.

When you read this I’ll be back on duty in the North Atlantic. If the gang gets after me for telling you a little bit about how tough war can be I’ll still be convinced I did the right thing. And I’ll tell them in turn that they underestimate you folks back home—that the truth is what you want and that you can take it.

Back me up. And buy more Bonds to get your man home—one year, one month, one week, one day, one hour sooner. . . .

THE END

It is a quote.PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JANUARY 1944