There Was A Boy—James Dean

PART II

WHAT HAS GONE BEFORE: In the first installment of this absorbing story, Bill Bast, who was James Dean’s close friend and roommate, told how Jimmy came to UCLA and became seriously interested in acting. He showed that Jimmy was a restless, searching youth, eager to improve his mind as well as his acting ability, and revealed how Jimmy’s early association with Hollywood made him decide to move to New York to pursue his acting career. But, even though Jimmy made progress, the thread of loneliness was ever-present, connecting the past with the present, sowing the seeds of his personal tragedy.

Late in 1951, equipped with only a few radio, TV, and movie credits, his meager belongings, a pocketful of change, and a short list of future contacts, James Dean slipped quietly out of Hollywood and headed for New York. He had barely started his career, and had only begun to develop his mind. But his mental appetite had been whetted, and he was off to a strange new place where he felt he would find much nourishment for both his career and his mind.

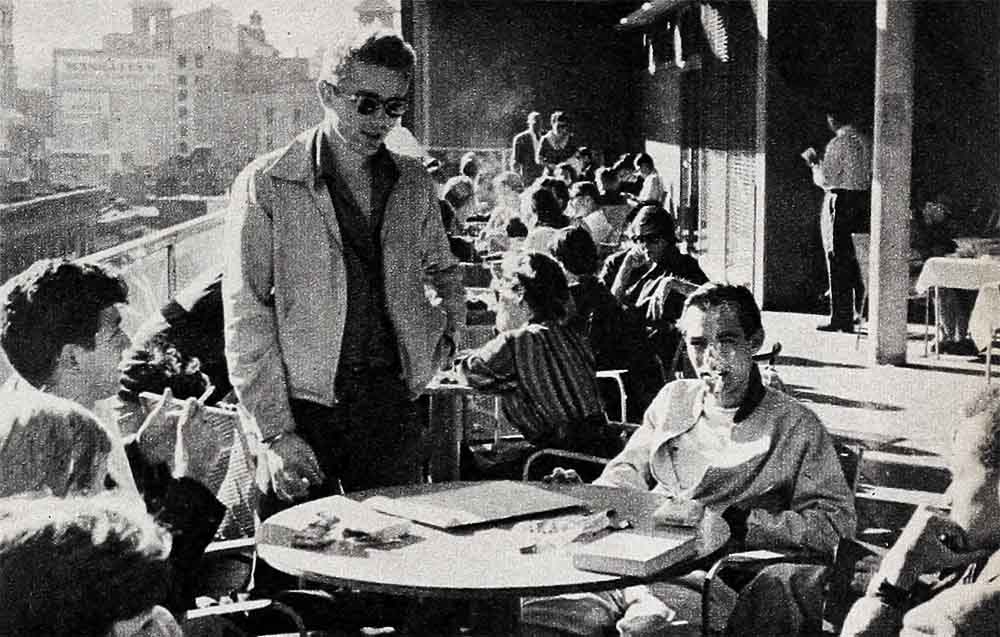

The first few months in New York were mildly successful ones for Jimmy. He utilized his handful of contacts and, through them, was able to secure several bit parts on radio and TV programs. Jane Deacy, then of the Louis Shurr office, became his new agent, and in a realistic way she made his future look promising. Slowly, Jimmy found new friends among the actors who hung out at Cromwell’s drugstore in the RCA building and at Walgreen’s in the Paramount building. Financially, things seemed to be in order, to the extent that he even bought himself a new suit, the first in years. Like his new suit, New York fit Jimmy very well. He was glad he had come East.

I had been offered a job in New York, but upon my arrival, I found it had been filled. Since Jimmy was the only person I really knew in town, I contacted him immediately. Over coffee at Walgreen’s he briefed me on the New York situation. We stopped by Louis Shurr’s office, where he introduced me and kidded with the agents and office girls. Then he made a quick phone call and we left to meet someone very important.

Jimmy had met Elizabeth (Dizzy) Sheridan a month or so before, and was completely captivated by her warmth, charm, and alert mind. Dizzy, the daughter of pianist Frank Sheridan, was a dancer—or, that is, she aspired to be a dancer. Alone in New York, she had taken a part-time job as usherette at the Paris motion-picture theatre, and was existing solely on her small salary. Somehow, she scraped together enough to study dance, her first love, and on rare occasions to go horseback riding, her second love. Dizzy had a wonderful sense of humor and was easy to know. It was understandable that she and Jimmy got on so well.

That afternoon, Dizzy, Jimmy and I took a walk through the zoo in Central Park, where it was decided that Jimmy and I should find an apartment to share. Jimmy had been staying temporarily with a friend and had been thinking of moving.

Apartment-hunting in New York, as any New Yorker will attest, is a fatiguing and complex chore. After less than one hour of looking, we gave up the struggle and compromised by taking a single room with bath at the Iroquois Hotel on 44th Street. The quarters were cramped, the rent was too high for our pocketbooks, but it put an end to a search that could have gone on for weeks.

Several members of Jimmy’s special circle of friends were living next door at New York’s famous old theatrical hotel, the Algonquin. Most of the people in the group were well established in the theatre or TV, and their acceptance of him was very gratifying to Jimmy. Prominent in the group was composer Alec Wilder, who wrote “Songs Were Made to Sing While We’re Young.” Alec had gained Jimmy’s respect and admiration and was responsible for slowly reactivating his interest in music and literature. Gradually, Jimmy began looking to both Alec Wilder and Rogers Bracket, another member of the group in whom he had a great deal of confidence, for advice and guidance.

The summer months crept on us and with them came the annual theatre and television disease, the summer hiatus. It is the time when many of the regular TV shows go off the air and the theatre becomes less active, leaving actors to either sweat out hungrily the muggy New York summer, or to take jobs in summer stock companies out of town. Jimmy decided not to try stock, but to remain in town and take his chances at getting work.

As the weeks went by and the work failed to materialize, Jimmy became more and more depressed. Summer in New York can be that way when you are not eating regularly. In an effort to offer him some relief, Rogers Bracket invited Jimmy for a weekend at the home of some friends who lived up the Hudson River. The thought of a refreshing weekend in the country appealed to Jimmy, and he accepted gratefully.

That was the first of several weekends he was to spend at the home of Lemuel and Shirley Ayers. Lem Ayers was a rising young Broadway producer, then working on plans for a fall production. Jimmy liked the Ayerses and, during his visits, he would spend his time puttering in their garden and listening attentively to the inside conversations about Lem’s forthcoming production of N. Richard Nash’s “See the Jaguar.” As time went on, the Ayerses came to like the quiet young man who came for occasional weekends. They were not aware, however, that somewhere in the back of Jimmy’s mind there glimmered a hope, a dream for the near future, which very much involved them.

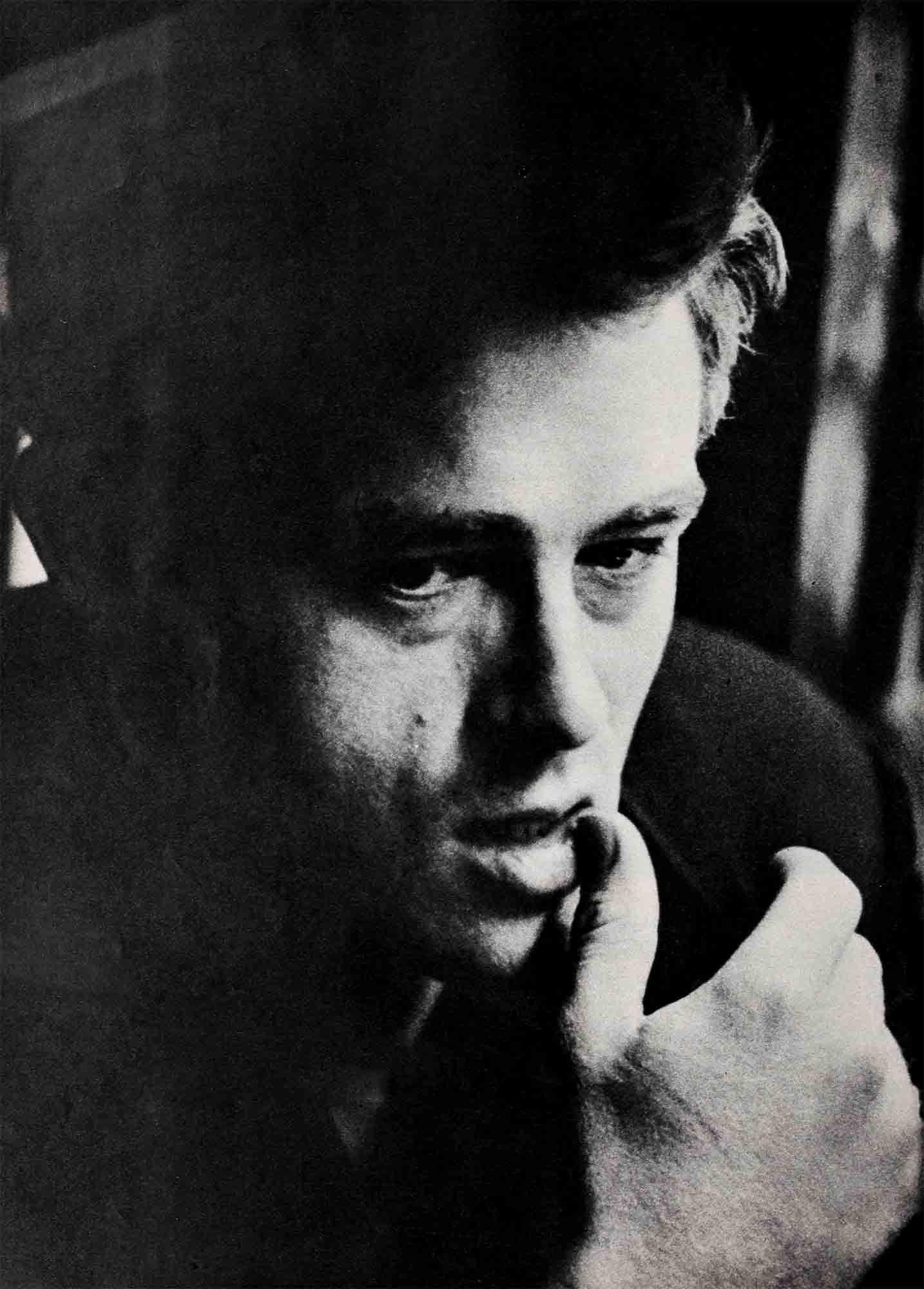

The weekends in the country made the days between in the city more bearable, but in spite of the relief, Jimmy’s despondency over the lack’ of work continued. He tried to spend his free time reading and studying. Even in his darkest hours he remained very active, meeting and getting to know new people, finding new and unusual things around New York, and discovering a little more about himself each day.

New York seemed to stimulate Jimmy’s mind to a point where it was more alert than it had ever been. One day, during a period when he had been reading a lot of modern literature, he asked me to suggest something in the classic vein to read. He seemed especially interested in Greek philosophy and drama, so I suggested he start with Plato. That night he turned up with a volume of Plato’s works and began reading a section on Democratic Education. After an hour or so, he closed the book and offered to treat me to a cooling beer at a bar near by. I knew Jimmy was an expert bluff artist, especially when he was in a corner, but I had never seen as vivid an example as I was about to get.

As chance had it, we ran into a friend of Jimmy’s at the bar. The man was a writer for Life magazine and was apparently well-educated. In less than five minutes, Jimmy had him deep in a discussion of Plato’s philosophy. Although he had read a mere twenty pages or so, Jimmy talked with the authority and enthusiasm of an expert. I am confident that when that man left the bar, he was thoroughly convinced Jimmy was a scholar of Platonic philosophy. However, I had discovered the secret of Jimmy’s little game: let the other fellow do most of the talking and you will learn what he thinks you already know.

One day in the office of his agent, Jane Deacy, Jimmy met an intense young actress named Chris White. Over coffee he learned that Chris had written a scene with which she wanted to audition for the famous Actors’ Studio. They agreed to do the scene together and began rehearsing immediately. Often they would come up to our hotel room and, using my objective criticism and direction, they shaped the scene with loving care and caution.

Slowly, things began coming his way. Slowly, Jimmy began to believe happiness might be one of them

By the time audition day rolled around, Jimmy and Chris had the scene beautifully molded. Frightened and nervous, they took their humble offering before what they considered the mighty High Priests of their craft. As I recall, they were two of the fifteen—out of the hundred and fifty who auditioned—who were accepted into the Studio. Jimmy was then reputedly the youngest member of The Actors’ Studio. He was twenty-one, and he belonged.

Late in August, the Ayerses invited Jimmy on a ten-day boat cruise to Cape Cod, stipulating that he was to act as a member of the crew. Jimmy had long been interested in boats and eagerly snatched at the opportunity to learn more about them. And, indeed, by the time he returned he had absorbed most of the basic rudiments of boating and navigation. For weeks thereafter he talked enthusiastically of boats and boating, but he avoided discussing the social aspects of the trip.

Out of a growing awareness that he needed people and had to exist in a world full of them, Jimmy had begun to develop a knack for complimenting their egos. This he accomplished by taking a deep and sincere interest in the things they liked most. By the time he took the boat trip, he had matured enough to realize that—in order to win the favor of the others on board—being friendly and genial, yet remaining true to his own character, was a simpler and wiser way to enjoy himself and to be enjoyed. When he returned, it was obvious that all had gone well and that he was due to hear more from the Ayerses.

Just before Jimmy left on the boat trip, we decided to give up our hotel room and accept the kind offer of a girl with whom we had studied at UCLA. So, in Jimmy’s absence, I moved our possessions into the large apartment the girl had been subletting and was turning over to us for the remainder of the summer. The arrangement seemed ideal, but we had hardly moved in when the people from whom the girl had been subletting returned from Europe and demanded their apartment. Helpless, we were forced to find a smaller place uptown.

The night before we moved out of the large apartment we were particularly broke, due to the advance-rent payment we had to make on the new place. Jimmy, Dizzy Sheridan and I had between us less than a dollar on which to eat. So, like scavengers, we took all the leftovers from the refrigerator and made with them a soupy stew into which we dumped a half-package of stale spaghetti. As we sat eating the mess, not one of us said a word.

All in all, that summer in New York was a torturous one. I had secured a low-paying job at CBS, but Jimmy was still suffering from the pressures of being unemployed. We had taken to pooling the little I had, the very little Dizzy had, and the occasional few dollars Jimmy picked

up by taking jobs on TV quiz programs on which they would throw pies in his face. Still there was barely enough to manage the bare necessities, such as food, rent, and cigarettes. It was no wonder, then, that about four o’clock one morn- ing over coffee in a hamburger joint, Jimmy, Dizzy and I came to the conclusion that we’d had it and decided to get away from it all. After a moment’s further consideration, we packed a suitcase, gathered together the ten dollars we had be- tween us (it was payday), and headed for the bus terminal, where we boarded a bus for New Jersey. Once there, we got off and hitch-hiked the rest of the way to Indiana, where we visited the farm on which Jimmy had been raised.

The two wholesome weeks we spent on the farm brought the kind of relief our tired souls required. The Winslows, Jimmy’s aunt and uncle, opened their home and their hearts to us. Mom, as Jimmy called his aunt Hortense, saw to it that we had plenty of delicious home- cooked food, and Marcus, his uncle, gave us the run of their serenely beautiful and efficiently clean, modern farm.

After all the years of seeing Jimmy alone and without a family, it was a wonderful thing to watch him touch once again the gentle roots of his early years. He discussed the farm and its problems at great length with Marcus, learning from his uncle the complications of farming in our present economic structure. Marcus seemed to beam with silent pride as Jimmy listened attentively, seeing in him for the first time a matured and developed young man who had, only a few short years before, left his household a mere boy.

Hortense was touched by Jimmy’s compassion and concern over her increased pain from the arthritis that had begun to gnaw at her hands. To Dizzy and me, Jimmy expressed a strong desire to offer the Winslows, someday when he made his fortune, the opportunity to move to a drier climate where Mom’s arthritis would not pain her as much.

Jimmy also spent many hours talking to and explaining things to little Markie, who is his cousin and the youngest of the Winslow children. Whenever he detected traces of his own character in Markie, Jimmy would expand with a secret pride and fond remembrance of his own boyhood days in Fairmount. He tried, in the brief time allotted, to encourage little Markie in all that he felt was important.

Jimmy took us to his old high school where, with a bit of his ego showing and the flourish of his own special brand of bravado, he took over for a few days. His dramatics teacher was more than pleased to see him, and turned her classroom over to the three of us. Jimmy spoke on the art of acting, Dizzy demonstrated modern dance techniques, and I got in my quarter’s worth by talking on TV directing and writing. None of us was really enough of a master of his craft to warrant this display of unabashed authoritative lecturing, but it was greatly rewarding to us to have those youngsters pay such close attention and regard us with so much awe. After a year of trying in vain to convince the New York professional world of our capabilities, it was a wonderful boost to have so many people accept us as masters of what we were trying to accomplish.

After too short a time, a call from New York for Jimmy brought our bliss to an end. We had slept well, been fed well, and had been accepted; we could ask for no more. Three grateful, refreshed young people were driven to the highway and deposited there to hitch a ride eight hundred miles back to the city, back to the task of finding their ways.

Our return brought with it great excitement. Shortly after we got back, Jimmy was asked to read for a leading role in Lem Ayers’ fall production of “See the Jaguar.” Jimmy had little hopes of getting the part, since another actor, who had been reading it during the auditions for the show’s backers, was almost set for the role. But it was the dream he’d had in the back of his mind all these months, and he was determined to do his best to make it come true.

His nerves were showing the night he went to read. He had no clean shirt, so I lent him one of mine. He was unable to manipulate his hands to tie his tie, so Dizzy took over for him. We agreed to meet him at the Paris Theatre after the audition. I went to the theatre with Dizzy and tried to concentrate on the movie while Dizzy worked out her hours. By the time she got off, Jimmy had not arrived, so we walked in the direction of the place where he had gone to read. We were halfway there when we saw him walking down the street toward us. We stopped, afraid to know the answer, and tried to discern from his expression what had happened. His face told the story. No one said a word; we just stood there laughing and crying like three crazy, grateful little kids. After many intense months of clinging to a slippery handful of faith and hope, the littlest part of a dream come true can be an exulting experience.

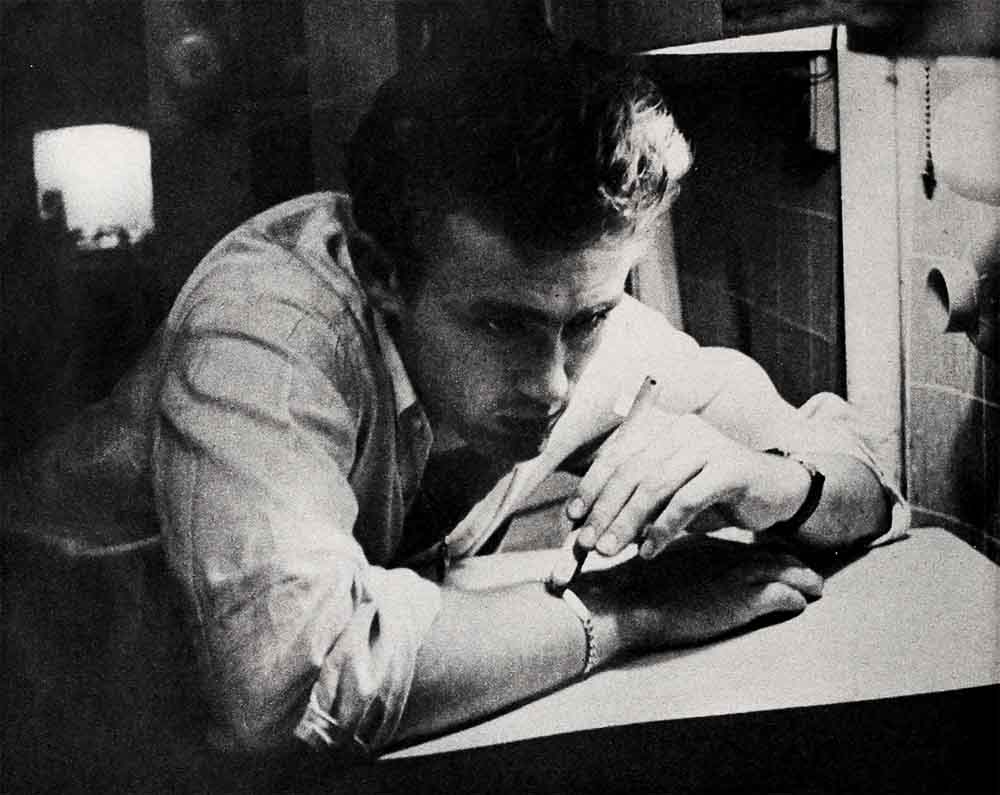

All of Jimmy’s hopes were riding on that play. It was the first time he had been afforded the opportunity to work closely with top professional talent, and he meant to absorb as much as possible. Immediately, he allowed himself to fall under the complete influence of his director and the star, Arthur Kennedy, and carefully followed their advice. The only difficulty he encountered was in trying to sing the folk song Alec Wilder had composed for the play. Jimmy was practically tone-deaf and had to be coached every evening by Dizzy or me, until at last he almost had it. During the four weeks of rehearsal, every thought he had, every conscious moment was devoted to his role. He was determined to make the most of this, his first appearance on Broadway.

Opening night in New York was especially tense for him. The out-of-town reviews of the play had been bad. Most of the critics panned the script, but they had been favorable toward Jimmy. His concern on opening night was, therefore. not as much for his singular success as it was for the over-all success of the show.

Anyone who saw his performance can attest that Jimmy did beautifully. He played a young boy whose mother had locked him in a smokehouse for many years in order to spare him from the cruelty of the outside world, and his portrayal was filled with sensitivity and pathos. The whole audience seemed to respond sympathetically and intensely to Jimmy’s acting. Backstage after the show, his dressing room was crowded with friends and well-wishers. Jimmy’s heart was filled with pride and gratitude. He had done well and he knew it.

The New York critics, however, did not like the script, even though they praised the acting highly, and the play closed after only six performances. However, as a result of his favorable notices, job offers started coming in for Jimmy almost immediately. The recognition and ensuing activity took the edge off his disappointment over the show’s closing. He was assigned several TV roles and got calls from the motion-picture studios. One such call was an offer to fly to Hollywood to make a screen test. Jimmy declined, insisting that a test could be made in New York, if they really wanted to test him. He had no desire to return to Hollywood, even to make a screen test. Ultimately the idea for the test was dropped, and Jimmy continued doing television work and auditioning for Broadway plays.

Several months went by without any major incidents. Jimmy continued to work, a little more regularly now, and studied even more intensely. He moved back to the Iroquois where he spent much of his time reading and learning to play the recorder, a flute-like instrument. Often he would sit in the window of his small room, piping out the sad strains of the folk tunes Alec Wilder had written for him to practice. Dizzy had gone off to dance at some place on Trinidad, and although Jimmy dated frequently, there was for a time no one to take her place. His anxieties were less than they had been during the past two years, but still he appeared to be waiting for something.

Shortly after I left New York to write for a TV show in Hollywood, Jimmy was cast in “The Immoralist.” I later learned from him that all had gone well in the early stages of rehearsal, but that the experience had ended badly. The out-of-town opening had proved Jimmy to be a highlight, but the show to be in need of rewriting and redirecting. A new director was brought in to take over and Jimmy’s part was drastically cut down. He had always shown a son-like attachment to any director in whom he had faith and confidence, but, either deliberately or unintentionally, this new director abused his confidence. As Jimmy related it, the director turned on him one day when he asked for guidance in his role. The experience so shattered Jimmy that he left the rehearsal for several hours.

Because of the cutting of his part and his disillusionment by the director, Jimmy gave his quitting notice the night the show opened in New York. In spite of the behind-the-scenes difficulties, the reviews of the show praised Jimmy’s performance highly. Jimmy settled down to fill out his contract and, once again, waited.

There is a point in the lives of men destined to be famous when Fate steps in and offers the perfect circumstance or vehicle to help them on their way to greatness. Once this opportunity has been afforded him, however, a man must assume the responsibility for following through and proving his worth. As James Dean prepared for his moment, another man—an active man with a power and greatness of his own—was preparing another of his many projects, a screenplay which he planned to direct. The lives of the two men had crossed occasionally, but briefly. To Elia Kazan, James Dean was an actor, a member of The Actors’ Studio, another actor to be watched and catalogued for future reference. To James Dean, Elia Kazan was a master of his craft, a champion of his school, a maker of his destiny.

It would have been normal procedure for any good agent to submit Jimmy’s name for a role in Elia Kazan’s production of “East of Eden.” But Jane Deacy isn’t merely any good agent. She is an intelligent woman with an acute eye for just the right thing, and when she read the screenplay for “Eden,” she knew it was just the right thing for her client, James Dean. So, in her own style (which shall remain a professional secret), she gave Fate a gentle nudge and nursed the situation, convincing all concerned that “Eden” was the perfect vehicle for Jimmy’s talent. Kazan was familiar with Jimmy’s work at the Studio and had been impressed by him in “The Immoralist.” He liked Jimmy and was soon convinced that he would fit the role of Cal in his forthcoming production at Warner Brothers. Jimmy was signed to do the part, then Fate stepped back to let him do the rest.

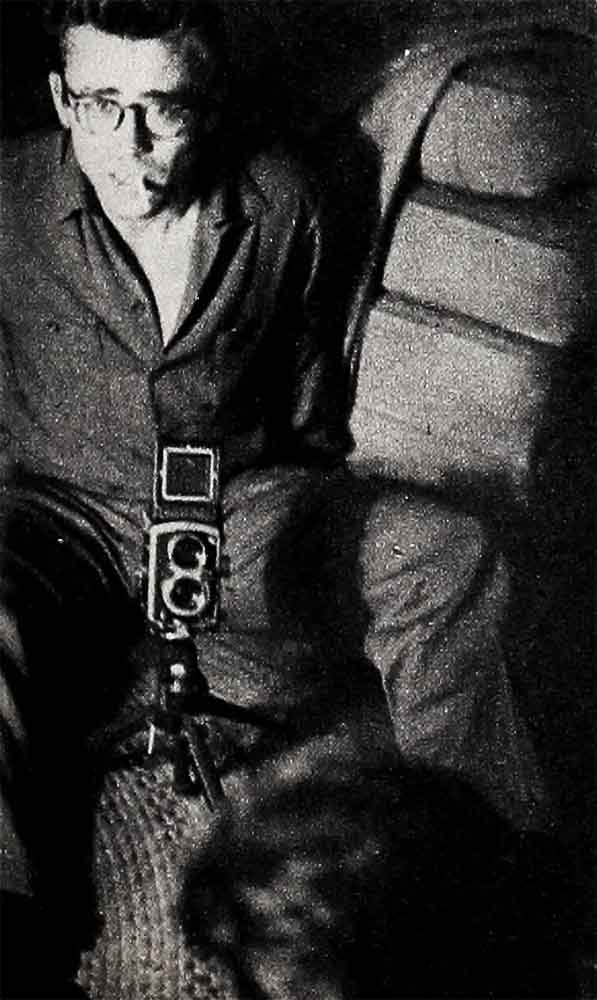

As a boy, Jimmy had had several motorcycles. In the years away from his home in Indiana, he grew to miss the thrill, the sweet sensation of whizzing along the roads and highways. As his pocketbook fattened, he found he had enough to warrant the purchase of such a luxury. New York is hardly the perfect place for motorcycling, but any place will do in a pinch, and Jimmy was in a pinch. He buzzed around town from appointment to appointment, storing the cycle in the entrance-way of his apartment building when he wasn’t using it. When people pointed fingers and called him “Brando-imitator,” he didn’t hear them. He knew what his motorcycle meant to him—they didn’t.

But, as it is so often with things you love, you get hurt by them. The week he was signed to do the role in “Eden,” Jimmy took a bad spill on the motorcycle, scraping himself seriously. Kazan had several strong words to say about the incident and concluded by instructing Jimmy to “stay off that motorcycle.” So, instead of cycling across the country to Hollywood as he had planned, Jimmy reluctantly stored the motorcycle, packed a few things, boarded a plane, and bade farewell to New York, the city he had come to love for all it had given him.

As he sat on the plane, watching the land between New York and Indiana beneath him, his dreams of the future were strange and unnerving. But they were not nearly as fantastic as the reality into which he was speeding.

Next month, Bill Bast tells about Jimmy Dean’s triumphant return to Hollywood, of his determination to live his own life on his own terms, of the people and events that had a strong influence on him, and the real truth behind the rumors that: he is still alive; or he committed suicide.

Concluding “There Was a Boy” in November Photoplay On Sale October 4

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE OCTOBER 1956