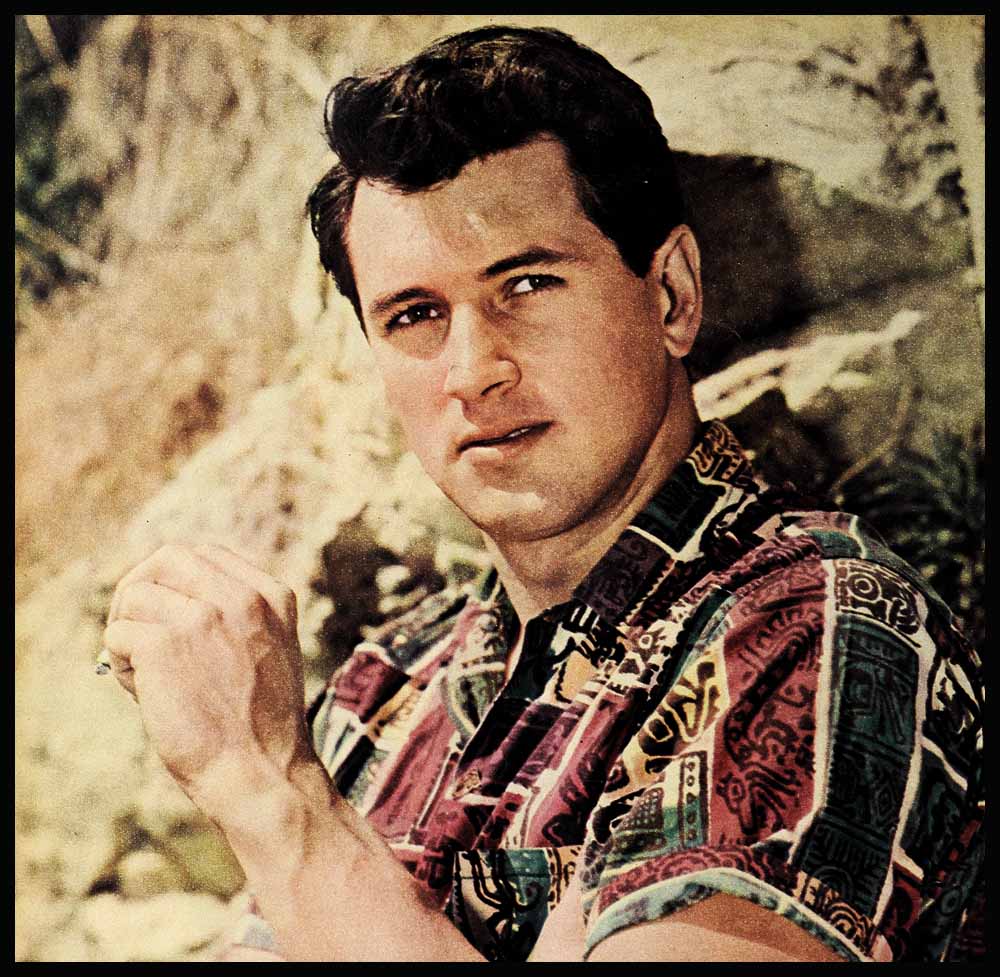

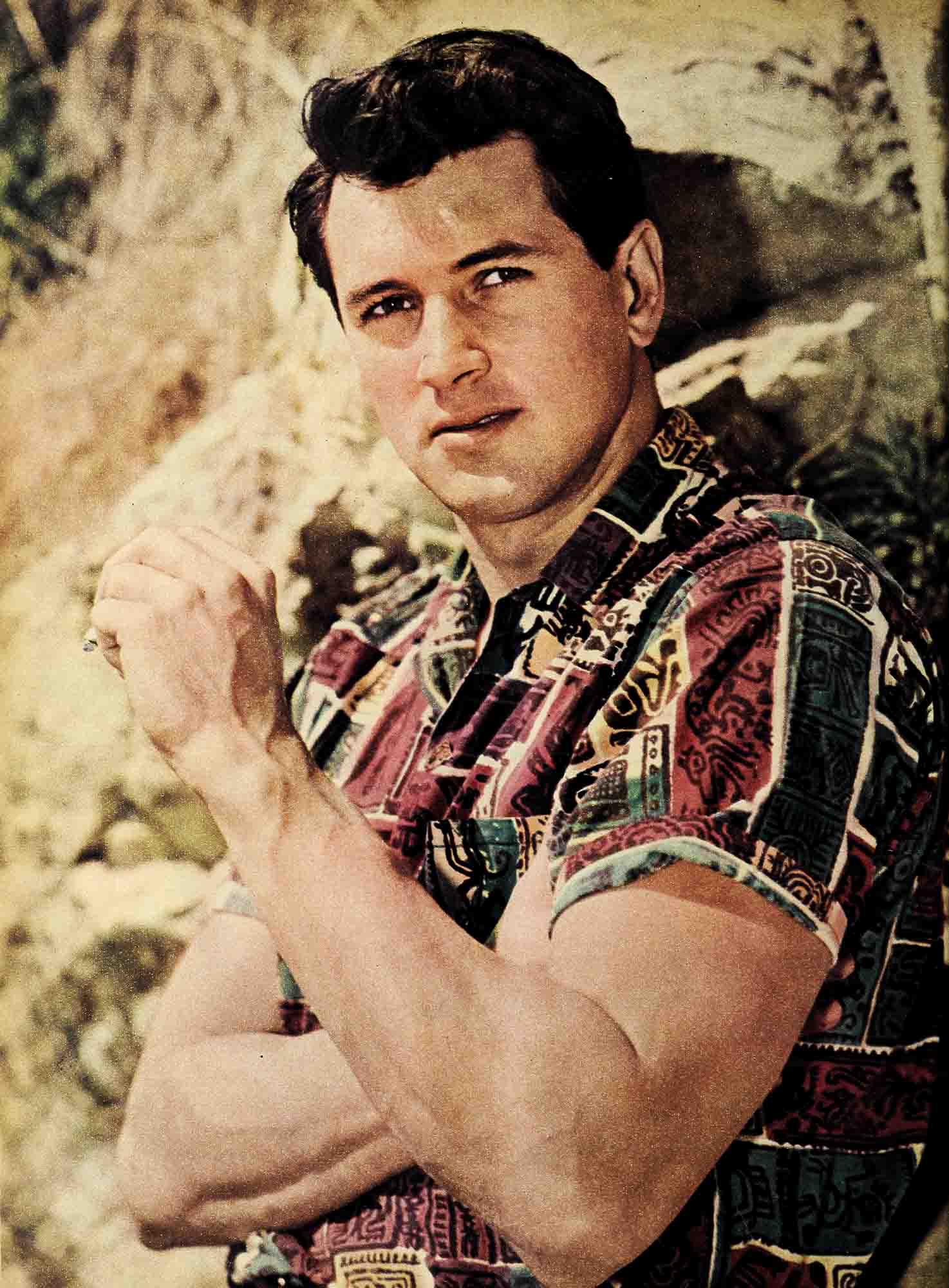

Rock Hudson’s Tip To Teen-Agers: “Don’t Call That Boy A Square”

Having nothing in particular to do one evening, I made a short hop over to see some old friends. We were all sitting around laughing and talking—having one good old gab fest—when the telephone rang. Conversation came to a fast stop as Joan, their teen-age daughter jumped from her easy chair, hurling the family pooch out of her lap, and raced to the phone as if the whole world were headed for that same call. A few minutes later, she was back again.

“That was quick,” her father said, giving her a hep look. “ ‘The Crumb’?”

“I don’t know why he keeps calling,” said our pretty heroine with disgust. “I wouldn’t be caught dead with him—let alone alive at the movies.”

“Why not?” inquired not-so-hep old Uncle Rock.

“Somebody might see us together.” She shuddered at the thought.

“New-type monster?” I asked pleasantly.

“Same old kind,” said her father. “There’s a crop every year, I understand.”

“Two heads—both square,” I guessed.

AUDIO BOOK

“Well, no,” grinned our girl. “But it might help. At least, then he’d have a choice. It’s just that he’s so laughable. Gawky. All hands and feet.”

“Jimmy’s an awfully nice boy,” the girl’s mother said. “And he comes from a fine family. Seems to me I remember a certain young lady who went through that gawky stage herself, not so long ago.”

“Oh, mother—I wasn’t rude,” said the girl. Then she flipped, “I even said goodbye before I hung up.”

Oh, brother, girls that age don’t know how cruel they are, I thought, because I have a few memories myself of a time when I was a gawky kid back in Winnetka, Illinois.

One of my teen-age loves was a girl named Nancy. It was the most beautiful name I’d ever heard. And Nancy was the most beautiful girl I’d ever seen. But something always came between us. In the classroom at New Trior High School, it was a distance of twelve desks. Outside the classroom, a fellow named Roy Fitzgerald was my worst enemy. And in case you don’t know, my real name is Roy Fitzgerald. And I was the tallest, thinnest, shyest guy in town.

Mentally, I waxed poetic about Nancy, comparing my love to the sun and moon and stars, not to mention Hedy Lamarr. However, when it came to speaking up, I was doing well if I could stammer, “Hello.” This eloquent speech seemed to take about as long to prepare as a recitation of the Gettysburg Address.

One day, at long last, I managed a good half-dozen words and asked for a date. Then I stood on my two left feet waiting her reply. “No,” replied Nancy. “I will not go out with you.”

I was shattered.

I looked up a buddy and we hitchhiked down to Booley’s Cupboard, a place near town, to drown my sorrows in a couple of milkshakes. We’d been there only a short while when my beloved Nancy and her friend Barbara came in. They nodded in our general direction but didn’t join us.

When we left, we noted that their car was parked out front. “Now why should we have to hitchhike all the way back?” asked my resourceful pal.

So we climbed into the back seat of the car and crumpled out of sight. Well, the seven-mile ride home was more like a hundred-and-seventy. With each mile, the girls’ conversation deflated me more. “That Fitzgerald boy in Booley’s,” began Nancy. “Know what he did? He asked me for a you imagine the nerve of him?”

“Are you going out with him?” asked Barbara.

“Are you kidding? Maybe silence is sup- posed to be golden, but I think it’s dull.”

“He’s probably shy,” offered Barbara.

“He’s a square,” said my beautiful Nancy.

Barbara giggled. “Who ever heard of a square bean pole?” And they both broke into hysterical laughter.

That was it. The end of the world. My world at the moment, at any rate. I was as tall as I am now, six feet five, and my 150 pounds consisted mostly of bones. I had no smooth manners, no easy line. I lacked the necessary social graces. And I wanted to cut the throat in which my words kept getting stuck and leaving me speechless. My voice? It wouldn’t change. Other guys could boom forth in their newly acquired bassos, but I was certain I was doomed to be a boy soprano for the rest of my life.

It’s called “the awkward age,” this phase. It comes to every boy and girl. Girls mature earlier than boys, however, grow out of adolescence and forget they ever went through it. And they leave their contemporaries of the opposite sex far behind. And this is what many girls simply don’t realize—and should.

As far as a girl is concerned, references to “that stage” are usually accompanied by words of reassurance that some day soon she’ll be a real beauty. She’s given credit for at least one redeeming feature—be it sparkling eyes, beautiful hair or a brilliant mind. As far as a boy is concerned, the awkward age is awkward for everybody. Someone once told me the amusing saying of a parent, speaking of his growing son. “The only time he stands up straight is when he can’t decide which way to lean,” said the father in a rather pained voice.

Teen-agers don’t intend to be cruel. They don’t mean to be thoughtless. But in a teen-age world, you either belong or you don’t belong. Nothing’s more important. And when you’re an outsider, no one gives a great deal of thought to acknowledging the fact that you’re alive. You simply don’t exist.

I remember one fellow in my class. He wore glasses and had braces on his teeth. These were temporary corrective measures. However, he could hardly go around shouting, “These won’t be here forever.” And let’s face it, he looked like a square sort of square. He spoke to no one. Primarily, I now suspect, because nobody spoke to him.

He wound up as an Army pilot in the last war with glasses and braces a thing of the past. The girls considered him one of the most handsome fellows in his air group. He’s in Panama today with his wife, who’s a real beauty. You never know.

Many times teen-agers judge one an- other on appearances. Teen-agers have to conform. And if they can’t, it isn’t always because they don’t want to. I speak from experience. Levis and sweat shirts were our class uniform. Came the time my mother bought me a new white shirt—slightly formal, mainly because it wasn’t a sweat shirt. I wore it several times out of deference to her. Then one day I heard someone snicker. At me? You know, I never actually found out. I just heard the snicker coming from some place and became very sensitive about it. So when I got home, I took off the shirt.

“l’m not going to wear it again,” I told Mother. “I can’t. It looks awful.”

Later, the sleeveless sweater arrived. My grandmother had knitted it for me. The color was khaki, and any jerk in our class knew better than to wear anything but red sweaters with sleeves. My solution to this problem was to throw the sweater away and then go home and vow Id lost it.

And what about the guy who’s neat in that blue suit, shirt and tie when the rest of his class is wearing levis? But how do you know that it’s not his family’s idea? He may rebel, but it doesn’t do much good. His folks are insisting that he become an individual long before he’s ready—and before his classmates will accept individuality. And that, my friends, is murder!

The awkward age is a time when a guy can’t seem to do anything right. And he’s clumsy when he tries. With his appearance against him, he winds up with a large type complex. He means well. And an understanding family can help immeasurably.

My mother is a jovial lady, with a fine sense of humor. Remembering the times I used to put my best foot forward and fall over it, I can laugh and she can have hysterics. But if she’d cracked a smile the times it happened, I’d have curled up and died inside.

We lived in an apartment. Once, when she was away, I decided to surprise her and paint the bathroom. It was a small room, and to brighten it, I selected a loud blue enamel. The stuff got all over the bathtub and a lavatory and mirror—and dried before I thought to wipe it off.

Mother came home and took a look at the room. “It’s beautiful,” she said. I was so proud of my handiwork I never noticed that only a short space of time elapsed before she completely papered the room.

I had a lot of good intentions that went haywire. Like the time she was in bed with a strep throat. I assumed that orange juice would help, so I went out and came back with oranges. Around ten dozen, I’d say. I squeezed every last one of them. We had orange juice in every pot, pan, kettle and pitcher in the house. There was, I recall, nothing left to cook in. But mother took it very well.

Understanding can do wonders for good intentions gone wrong. It can do wonders, period. Winnetka, Illinois, was a wealthy town. And the Fitzgeralds were somewhat less than wealthy. One of my chums, whose family was a prominent one, arranged for me to go to dancing class with him. Such activities are usually viewed with horror by the participants, but this was considered fun by everyone concerned because Miss Pratt, the teacher, was a genuinely nice woman. She used to ask me to help whenever she was illustrating a new step. She was tall and I thought she preferred me as a partner because I was the tallest guy in the class. Now I realize she must have sensed my terrible lack of assurance and wanted to help me. Gradually, I began to acquire some social poise. My height wasn’t so disgraceful after all. Miss Pratt let me attend the classes for free for the next three years, letting me feel that I was contributing to the lessons. It’s only recently that I realize how kind she was.

I really needed help! I can’t blame girls for not stopping to understand what agonies their male contemporaries are suffering. And, as a kid, I didn’t help the girls either. It rarely occurred to me to tell a girl how nice she looked. And when it did occur to me, I couldn’t put the sentence together. I’d blurt out crazy things and I didn’t mean them the way they sounded.

“You sure look funny,” I once said in an effort to tease a lovely young lady. She found this non-funny. I was bewildered.

My party patter was also brilliant:

Girl: “What are you taking in school?” Me: “Oh, a few subjects.”

(Silence)

Girl: “Seen any good movies lately?” Me: “Some.”

(More silence)

Girl: “Read any new books?”

Me: “Yeah.”

When she’d given up her conversational effort, I could think of a thousand things to say. Only time had crossed me up. Ten more minutes, I’d think, and I could have been the life of the party. As it was, I was the death of it. Those were tough days—or I thought they were.

I was remembering all this that night I overheard my friends’ daughter taking such a superior attitude toward a boy who must have been much as I was at that age.

“Have you ever thought that maybe ‘The Crumb’ has feelings?” I asked her. “And that quite possibly he’d like to be one of the crowd?”

“I guess I never have,” she admitted. “He could have been in China as far as been concerned. He’s just never counted.”

“He must like you,” I said. “Or he wouldn’t be calling. Doesn’t he have any redeeming features?”

“Well,” said she. “He’s pretty smart. Ina bookish way. And he does have kind of a nice smile.”

“Could you bring yourself to smile back at him sometime—and mean it?”

She grinned. “I just might,” she said.

As a matter of fact, she did. You see, this happened a while back. By no stretch of the imagination could I call myself Cupid. But now they’re going steady. And the word “Crumb”? She’ll tell you it’s strictly for the birds.

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JULY 1954

AUDIO BOOK