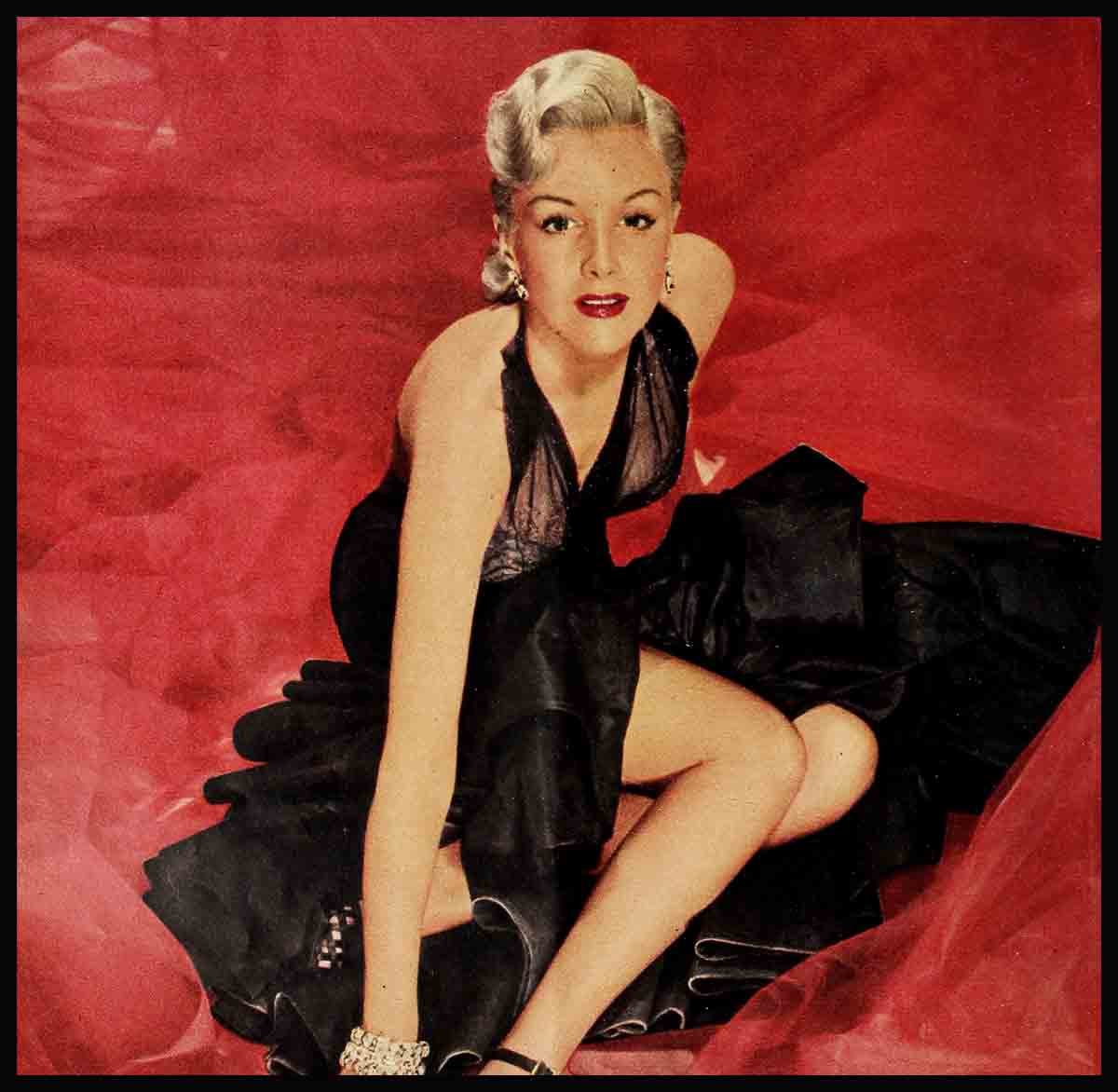

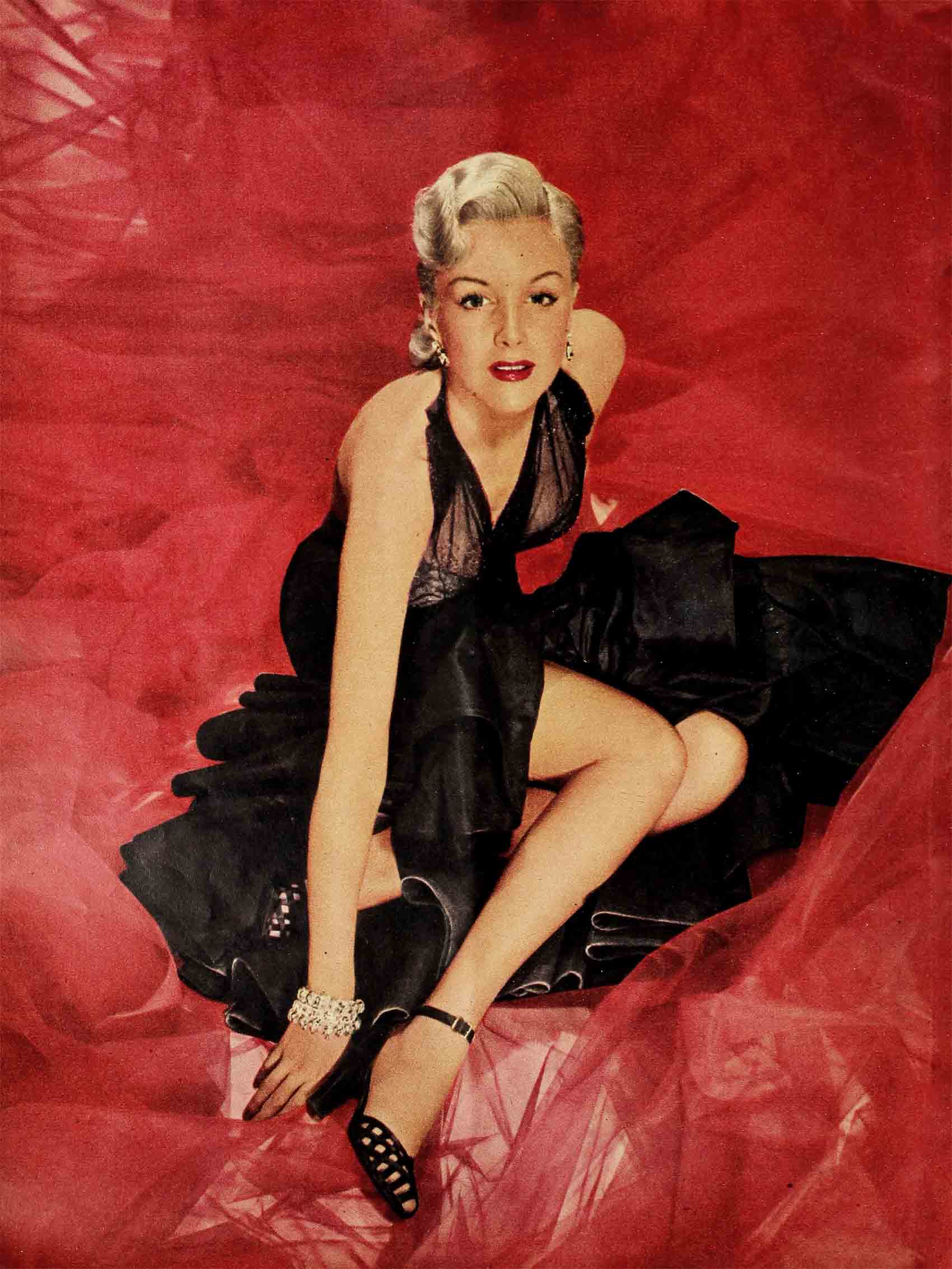

When I Hated My Mirror—Jan Sterling

In Rio de Janeiro there is a restaurant called Soveteria Americano which used to specialize in American delicacies for the young. Among the most scrumptious was one listed as Sundae Nova York: vanilla ice cream covered with hot fudge sauce, smothered with whipped cream and heaped over again with malted milk powder. It was served with hot buttered toast thickly topped with grated, tasty yellow cheese. Time will never wash out the agony of an afternoon in which I sat in this restaurant watching my 11-year-old sister eating such a concoction before my envious eyes. What I had in front of me was just a glass of water. I was only 14 but I had begun my fight.

Everyone called Mimi adorable. With her curly hair, her slimness and delicate curves she was lovely. Me? They would cast a quick glance, smile kindly and assure me, “Why, Jane, you look fine,” The devil I did! I already weighed 145 pounds. I could see 155 coming up, 165, 175 . . . and it was horrifying because in my heart had been a vision from earliest childhood that I could not give up. I yearned to be an actress, a queen of women, a supple, graceful creature who drew admiring looks from everyone. With this in my heart I could only detest the flesh I was picking up, and I couldn’t understand why this wasn’t apparent to everyone, including my own folks.

It had all started when I was 11. I already had begun to develop in a way that would have been gratifying had it been confined only to certain places. (As a matter of fact, at 13 I attended an Annapolis hop in a low-backed gown and must have passed for at least 17 or 18 because no one at all seemed to notice my juvenility.) But I didn’t stay pat. I began to bloom elsewhere too, where it wasn’t wanted and where it could only be called thickening or fattening. The morning of that day in.Rio de Janeiro when Mimi was gobbling up her Nova York I had gone to the mirror knowing it was time to believe, not the assurances of my family and friends that I had nothing to worry about, but exactly what the glass told me. I looked and what I saw was cruel. I hated my mirror for its heartlessness . . . but I bowed before its truth. That day I started a way of eating that was, of course, a way of living from which I have never departed. At 15 and 16 and 17 and 18 I was not 155 or 165 pounds or more, I was only 122 pounds. And my dream came true . . . or rather I had made it come true under the constant guidance of my family doctor who checked my diet and rate of losing weight.

That 122 pounds was fine for an actress on the stage but it wasn’t good enough for an actress on the screen. So I called on will-power and medical help again. Today I weigh only 108 pounds—and there have been other changes. As it happens I am the fourth wife of my husband, Paul Douglas. But the way he puts it now, after some of those changes, “You’re both my fourth and fifth wife!” That’s nice “changing!”

When I was about six my parents divorced and my mother remarried. My step-father, Henry James White, was an oil man with interests in both Europe and South America, and we seemed to beat a constant path between these two continents and the United States. Most of my education came from tutors and in my whole life I have had only one year of formal schooling. That suited me because no matter what subject I studied I always translated it in terms of the stage. History to me was full of characters with costumes and good or bad lines to say rather than people of political or cultural significance. English was something you talked—not wrote or analyzed. Geography concerned places where there were different forms of entertainment; opera in Italy, intimate theaters in France, outdoor concerts and folk dramas in Austria and Germany, weird all-day shows in China.

All my life I had always wanted to play at being someone else . . . but I didn’t know my first big role would be the real-life one of simply not being me. I think the customs of my family cemented this desire. My mother, like many mothers, used to dress Mimi and me alike. I think this is a practice which pleases the parents, is complimentary to the younger girl, but darn unfair to the older one. I still remember the sack-like dresses we wore—the kind that hang straight down, when Mimi was seven and I was ten. The minute I’d get alone I’d find something, even if it was only a piece of string, and pull it around my waist, trying for a shape. And then . . . the bloomers! I tried so many experiments trying to unbloomerize them that generally I’d wear out the elastics and time and again these would break and I’d be all bloomers down to my ankles.

I gave my first performance for other than children at the age of nine. The audience was composed of the elevator operators in the apartment building we lived in on Park Avenue in New York at the time, and the stage was the lobby. When the operators agreed to watch my “show” I ran out to the drug store and bought theatrical make-up for myself. I always wanted to be professional. At ten the family was back in London and I persuaded my mother to get me a permanent. But then I didn’t like the color of my hair, which I correctly called “dirty blond” and started experimenting with bleaches. I’d buy these myself, do the rinse myself, and almost always end up with a mess; the color settling in the parts which had been curled.

I know I was a source of constant upset to my elders. My step-father’s attitude toward me was one of astonishment as if he couldn’t understand what made me so restless, so discontent. Once he had most of the gendarmes in Paris looking for me because despite winter weather I was gone from the house all day. When he learned what I had been up to he was completely perplexed; he couldn’t even understand why my mother could understand. It was just that I was a Jean Harlow fan and, having written her a letter and figuring it was time for a reply, had been hanging around the home of a friend where I received my “secret” mail. Harlow, and Constance Bennett (with her divine, thinness!) were my idols.

This is what was buzzing inside of me and keeping me a harried young miss. When my family assured me I looked all right I instinctively felt I was being lulled into false security. When I talked about the stage they wouldn’t believe I was being motivated just by thoughts of a career. They hinted at boy friends, that I was responding to the call of life rather than the call of drama (as if one didn’t, somehow, go with the other!).

“It isn’t right for a child to worry too much about the future,” my step-father said. “There is plenty of time. You’ve got too much drive in you.”

I wanted to believe him, and to some extent I did, until that day in Rio. From then on pastries, starches, fats of any kind, were practically out of my life for good. When I recoiled from the mirror I sat down and did some realistic thinking. The girls whose shapes I envied—they weren’t any different than me under the flesh. I knew enough about anatomy to feel sure that our skeletons were exactly the same. It was just a matter of how much fat and muscle you had covering it—and where. That would be up to me. I liked my eyes, I could cope with my mouth which I thought was too small, and mascara could handle eye-brows that were far too blonde. My choice was clear. Was I to be a contender for the world of my dreams or was I going to give up? The answer came to me instantly—if I couldn’t be the best looking girl in the world I didn’t want to be anybody! (Actually I knew I’d never be, but I wanted to get close enough so that there could at least be some hopeful and wonderful confusion about it!)

Lord knows it was hard at first. I’d eat a sensible lunch and then still crave for something. After the first four or five days it wasn’t so bad. And in time, that same year, came my reward. The first time I stopped taking a size 14 dress for a size 12 I knew it was going to be worth it. I smiled deep into my insides, feeling so elegant, so feathery, that I loved the whole world. For the first time I began to accept myself as a person whom I would be willing to live with for the rest of my life.

I remember my mother saying one night, “Darling . . . you’ve been losing weight.”

“She doesn’t eat anything,” my little sister said, accusingly.

I didn’t reply. I was brimming over with a good feeling and my eyes must have been full of it. My mother, who had been going to argue with me, sensed it and changed her mind. “Well . . .” she said, and shrugged. But there was both respect and admiration in her manner; not just mother for daughter, which any girl can get, but woman for woman, if you know what I mean! My little sister sensed it. Something must have penetrated through to my step-father because he studied us all and then apparently decided not to intrude into the feminine mysteries going on around him. Something was happening in the family all right . . . and that something was me!

That old saying, “Him who hath, gets,” is not exactly right in my estimation. It should be, “Him who goes out and gets . . . can get again!” I had gained respect in my family. On the strength of it I was able to put over something I would never have been able to . . . starting from scratch. Mother had kept Mimi’s and my name in the New York Social Register and had planned this year to start me in finishing school at Farmington, Connecticut. But I thought it was time for me to start being an actress rather than waste time preparing to be a debutante. I had no interest whatsoever in confining what I thought was a great talent on a closed circle of bluebloods; the world was where I wanted to play! I put on a campaign towards that end which involved arguments, minor and major hysterics, and plain defiance. In the end I got a small concession, principally because I had proved I wasn’t just a little girl. I could go to New York and have a month’s time in which to find a job in the theater. If I failed it was Farmington for me. I’d be “finished” one way or another.

At that time I listed my assets as follows: name, Jane Sterling Adriance; age, 14; stage experience, years of it in my mind if none in actuality; beauty—I felt like one! I neglected to consider something that proved to be most important. In the years we had spent in London I had picked up an English accent (which years later I was to work hard to lose). One afternoon I accompanied a friend to the Shubert offices and one of the famous producer family, Milton Shubert, heard me talk. He was casting a play to be called Bachelor Born, and needed a girl with a veddy, veddy British accent.

“What’s your name?” he asked.

“Jane Sterling . . .” I began slowly, sounding off with all the Mayfair I could.

“Excellent name!” he cut in, and offered me the part right then and there. I wrote mother and she was properly shocked. Mimi was delighted. And my own father, William A. Adriance, who was in New York at the time, found consolation only in the fact that Milton Shubert hadn’t heard my whole name and thought of me as just “Jane Sterling” without the “Adriance” attached. Later on I cut Jane down to Jan at the suggestion of a theatrical friend.

On the stage there are no close-ups, you are there in person and in color instead of in black and white which can accentuate faults. At 122 pounds with my height of 5 feet, 5 inches, I considered myself perfect. And nothing ever happened to make me change my mind until six years later when I began seeing myself on the screen. One look—and, a little sadly, I said to myself, “Here we go again.”

At my height all the beauty authorities said my weight was perfect . . . but the screen disagreed. It said I was fat. It said that my hips were too big, the upper part of my arms, and, I knew, the upper part of my thighs. It said that because my cheek and jaw bones were small there was an impression of fatness in my face in closeups. I admit I felt like rebelling but, as the saying has it, go argue with City Hall! There was nothing to do but shut off even a bigger part of my stomach. I ate nutritious foods; eggs, hamburger, steak, tomatoes. Nothing else. I controlled the distribution of weight with massage and with exercises—but posture exercises only. From childhood on I had had a fear of developing muscles that would go flabby when I quit exercising them. And instead of getting on the scales daily I walked into the wardrobe department of Paramount Pictures one afternoon months later to check results a different way.

I knew that they kept a dummy of my form on which to check costume measurements and that it was constantly altered to conform to any change in my own dimensions. “Have you had to do anything about it?” I asked the wardrobe mistress.

“Yes,” she replied. “We’ve had to take it in two and a half inches practically everywhere.”

That’s all I wanted to know. I got on the scales and I was 108 pounds. Perfect . . . except it wasn’t. When I saw the rushes of my next picture something else hit me. At 108 pounds my face had lost its fatness all right but in such a way that my nose was too prominent . . . and I realized that my nose was of a kind which could not stand concentrated attention. “Not a nose bobbing,” I thought to myself. “Not that!” But I knew darn well, that very second, that it was to be exactly that.

The facts were as plain as the nose they had to do with. My nose at the top started flush with my forehead and stayed flush—there was no inward dip, no rétroussé or tilt. Further, the high bridge was not only flat, instead of rounded, but much too wide and flat. You may wonder, in view of an itemized list of defects like this, why my nose had not perturbed me before. The reason is that I had always considered it an individual nose, one which helped to make me me, and when my weight was higher it was not at all a bad nose. But with the more delicate modeling which characterized my whole build after I reduced, every defect about it stood out too sharply. There was no doubt about it . . . it had to go or I’d never be really self-confident before a camera again!

First I talked to my husband, Paul, about it. Then, because the studio had invested heavily in me, I discussed it with them. After this I mentioned the idea to friends. In the end it was up to me . . . nobody opened up my eyes to anything I hadn’t already thought of, either beneficially or otherwise. Paul said simply, “I liked you as you are well enough to marry you but if you want to go ahead I like you well enough not to deny you my blessing.” The studio officials were wonderful. They were grateful for my thinking of their interest in them but what I planned was a personal matter. They urged me not to consider them in any way. My friends said everything from, “Great!” (which was oddly uncomplimentary) to, “What do you want to do that for?”

I paid exactly $1,000 for everything connected with the operation. The doctor—and I made sure that he was a good one—hummed and sang while he worked, and I heard him because the anesthetic was a local one. There was no pain. It felt as somebody were fumbling with my nose but there was no greater discomfort. Once I knew the nurse was handing him some instrument and after a moment she said, “Well! That little gadget didn’t work out, did it?” I couldn’t help bursting out with a cry. “What little gadget?” I wanted to know.

For about three days my eyes were discolored and that was all. Two weeks later I was entertaining in Korea and when an army commander leaned over to kiss me during a presentation ceremony (they gave me a tank on condition I leave it in Korea and, not needing a tank at the moment, I did) the rim of his helmet hit me right on the bridge of the nose. I nearly pased out from the pain, and felt sure that there was nothing but a squashed blob on my face. But there wasn’t a mark and my pretty reborn nose was just as pretty as before.

Paul was pleased, I know he was, but like a man will he just grinned and said, “Well, now I have a new place to slug you.”

Well, it may be a new place to slug me but it is a much smaller place than before. You know the mirror I hated? Well, after a nose operation you don’t hate your mirror, let me tell you. For months afterwards I couldn’t stay away from the mirror. “Is that really you?” you keep asking yourself. You do this because you love the thrill of answering. “Yes! Really! That’s you!” And sometimes I add, “And that’s the way you should have looked all your life.” But I’m satisfied. Satisfied and happy.

Now whenever there happens to be a moment when I feel low I just pull out the mirror, look, and a big smile spreads all over my face. “Well! Well! Well!” I think to myself. “Look at me! Well! Well! Well!”

THE END

—BY TOM STERLING

(Watch for Jan in Paramount’s Pony Express. Paul’s latest film is Forever Female, also for Paramount.)

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE MAY 1953

No Comments