The Day Was Thanksgiving—Bette Davis

The time was eleven years ago. The place was Tudor Close Inn at Rottingdean on the English coast, 60 or 70 miles from London. The girl was Bette Davis.

She stood at the window of her tiny room, and you’d have thought she was enjoying the view, lovely even in late autumn. But you’d have been wrong. She didn’t even see the view. Her eyes were turned inward, and what she saw was a wall—high, blank and hopeless.

She’d fought, and been licked. All her dreams since she was old enough for dreaming lay toppled in ruins. It seemed one of those nightmare things, incredible in the light of day. She was broke, jobless, desolated.

The room was cold. Should she put a shilling in the meter and get some heat, or go down to a solitary luncheon? Neither prospect offered much cheer. Tudor Close was a lovely inn, but for good and sufficient reasons she’d taken its smallest room, and with her trunks standing packed, she could just about thread her way in and out. Downstairs she’d sit with her dreary thoughts for company. No chance of distraction. The British were a sterling race but, like the Yankees of her own New England, far from social. You’d have to stick around the place a good six months before they’d say hello.

Well, George Arliss was coming to tea, and tomorrow she’d be on the boat train for Southampton and home. Tomorrow was the 27th, she’d be in New York by—Wait a minute. Tomorrow was Friday—the last Friday in the month. Then today was the last Thursday; today was Thanksgiving!

Imagine forgetting! But there’d been so much else crowding in, and nothing to remind her of her own American holiday. In England they had no Thanksgiving. Naturally. No Pilgrim Fathers, no Plymouth Rock, no Thanksgiving. But across the sea there’d be snow in New Hampshire maybe, and if not snow, then that beautiful zing! in the air, and you’d take a walk for the simple pleasure of breathing it, and scuffing the leaves underfoot, and watching clouds scud high through the blue overhead. Then back to the fire roaring and the turkey roasting and the family gathered round.

Twisting, she flung herself face down on the bed, and let the storm of misery tear through her.

This was the climax of what had started months back.

Over a period of time, Bette and her bosses had differed on the subject of pictures. Who was right and who wrong is no concern of this story. Let’s play it cagey, and say there was much to be said on both sides.

So we arrive at a picture called The Man with the Black Hat, which nobody mentions now, and we touch on it briefly only because of its part in advancing the plot. Against every instinct, Bette made it, dusted her hands off and decided the next one would have to be good, or the law of averages was certainly going to the dogs.

Up comes the next one. “This,” said our forthright heroine, “is the most diabolically boring script I have ever read.”

“It is nevertheless the script of your next picture.”

So Bette walked off the lot.

two irresistible objects . . .

Now there’s nothing phenomenal in that. Stars walk off lots every Monday and Thursday, and after a while somebody makes an overture and the star comes back, and everything’s divine again. Only this time nobody made an overture. Firm in the right as God gave them to see the right, the parties of both parts stuck to their guns. Allowed to stay off the screen for months, Bette’s position grew ridiculous. An actress who wasn’t permitted to act. Not to mention a bank account battered by the law of diminishing returns.

At this juncture, a producer named Toplitz rushed in where others feared to tread. Would Miss Davis make a picture in England? Miss Davis would adore making a picture in England, but she was, after all, under contract to Warner Brothers.

The contract was studied under a lens. The consensus of opinion was that in England it wouldn’t be binding.

“But if I’m injuncted,” said Bette, “are you willing to fight it in the English courts?”

“If you’re injuncted,” Toplitz agreed, “we’ll fight it.”

Well and good. Bette packed. But every time she caught sight of a man with papers, she’d duck. On the advice of experts, she flew to Vancouver, trained across Canada, sailed from a Canadian port. By the time she set foot on English soil, men with papers had lost a certain sinister quality.

Till a courteous voice at her elbow said, “Miss Davis?” And a courteous man with a paper handed it to her.

Recovering from the shock, Bette’s She’d have had the thing to fight sooner or later. Okay, gentlemen, let’s get it over with.

The law was in no hurry. First, you waited for the preliminary hearing. Then for the judge’s decision as to whether the case was worthy of trial. It was. Then you engaged counsel. Then you fooled around two months more till the case came up.

During these months she discovered the little inn at Rottingdean, where living cost so much less than in London. Loneliness was better than crowds who stared, and newspaper people who asked questions you wouldn’t have answered. even if your counsel hadn’t warned you to keep quiet. Not till the evening before the trial did a slim, gray-suited figure slip into a London hotel and sign the register.

“I want a back room,” she said, “away from the street.”

That sounded nice and elegant, as if one couldn’t endure the noise of traffic. It was nobody’s business that one couldn’t afford a front room.

The trial lasted four days. Now, even in England, where journalism is supposed to be less flamboyant than ours, any movie star makes news, and a battling movie star is good for headlines. But the quiet girl in the courtroom proved disappointing. The press craved drama.

All Bette wanted at the end of the day was to make that back room, and stay there. All the newshounds wanted was news. Morning and evening they waylaid her. First they were baffled, then they grew desperate. Failing everything else, they picked on her clothes. Ah Hollywood, ah luxury, ah purple and fine linen—ought to be color there. But Bette wore the same gray suit with a change of blouses.

“How about another outfit tomorrow, Miss Davis?”

“Sorry, this is the only suit I brought along.”

From this, some enterprising scribbler—probably a husband—whipped up a feature story, slanted at wives. “Bette Davis,” he chided, “wears the same suit in court every day. Who are you to want more?”

She couldn’t get back to Rottingdean fast enough. There she waited again, but with a difference. Now everything hung on the judgment of one man. A kindly man—that was clear from his manner. But kindliness had nothing to do with the law.

At first, things had seemed to be going her way. Then some legal twist had sent them in the other direction. Now, where the balance would fall was anyone’s guess.

Don’t think, she cried to herself, try not to think of anything, put your mind to sleep. But you couldn’t keep the surge of agonizing suspense from rising every so often to suffocate you.

Toplitz phoned the day before the verdict was to be read. “Don’t you want to come up to London to hear it?”

“That,” said Bette, “is the last thing in the world I want.”

“Very well, then, I’ll phone you. Keep your chin up.”

Good old Toplitz, good old England, keep your chin up. How did you keep your chin up when you were a mass of quivering nerves? How would she ever get through this night?

People are tougher than they give themselves credit for. She got through the night and some hours of the following day, and across the room to the phone when Toplitz called.

“I’m sorry, the verdict’s against us.”

At first, the blow had been cushioned. Before she’d really taken it in, Toplitz had added: “But I think we can still make the picture. I’m coming right down to talk it over with you.”

She hung on to that. If they could still make the picture, if she could work, if she could go on fighting, then there was hope. Toplitz must know what he was talking about. She watched the hands of the clock crawl round, she stood at the window, mentally pushing his car along the London road, she flew down to meet him when at last he turned into the drive.

one more chance . . .

His plan was simple. They’d make the picture in Italy. There wasn’t a thing anyone could do to stop them. He’d gone over and through it and criss-cross, hunting for loopholes. looked as if they’d be strictly legal in Italy.

For a day that had started so black, it wound up all right. That evening a cable came from Ruthie. the verdict, Bette’s mother had packed bag and baggage into a car, reserved space on the next steamer, was even now tearing cross-country and would shortly be with her daughter, car and all. Ruthie to the rescue, bless her, as she’d dashed to the rescue on so many other occasions.

Then the crusher fell. releasing company in the States. Terse and unanswerable. Wherever it was made, they wouldn’t touch a Davis picture.

“We’re licked,” said Toplitz. “We’re licked 100 per cent, and we might as well face it.”

At a dock on the New York waterfront, they were lowering a dusty car into the ship’s hold as one of the passengers raced to the purser’s office.

“I’m sorry, youll have to get my car ashore. I’m not sailing.”

Her hand clutched a cable. “Have to come home,” it read. “Leaving Friday, the 27th. Wait for me there. Bette.”

She lifted her head from the pillow. Well, now she was really through with tears, if only because there couldn’t be an ounce of moisture left in her. Come on, do something useful. What, for instance? All but the last-minute stuff was packed.

She must look a sight. This the mirror confirmed. Better start making herself presentable before her guest arrived. Wringing out a towel, she lay down again with the damp coolness over her eyes.

Think of something pleasant. All you’ve got to be thankful for today—health, family, friends. Think of your friend, George Arliss.

“I’d like to come down to see you on Thursday,” he’d written. It was so gracious of him, to make the long trip from London. But he’d always been kindness itself. Since that faraway day in Hollywood.

She’d been ready to return to New York, convinced that she and the movies could never mean a thing to each other. Then the phone, and a voice saying, “This is George Arliss,” and the incredible wonder dawning that it was George Arliss, and he wanted her for a picture called The Man Who Played God.

That was the beginning, that was the picture she’d clicked in. And this was the end. Her head moved wearily.

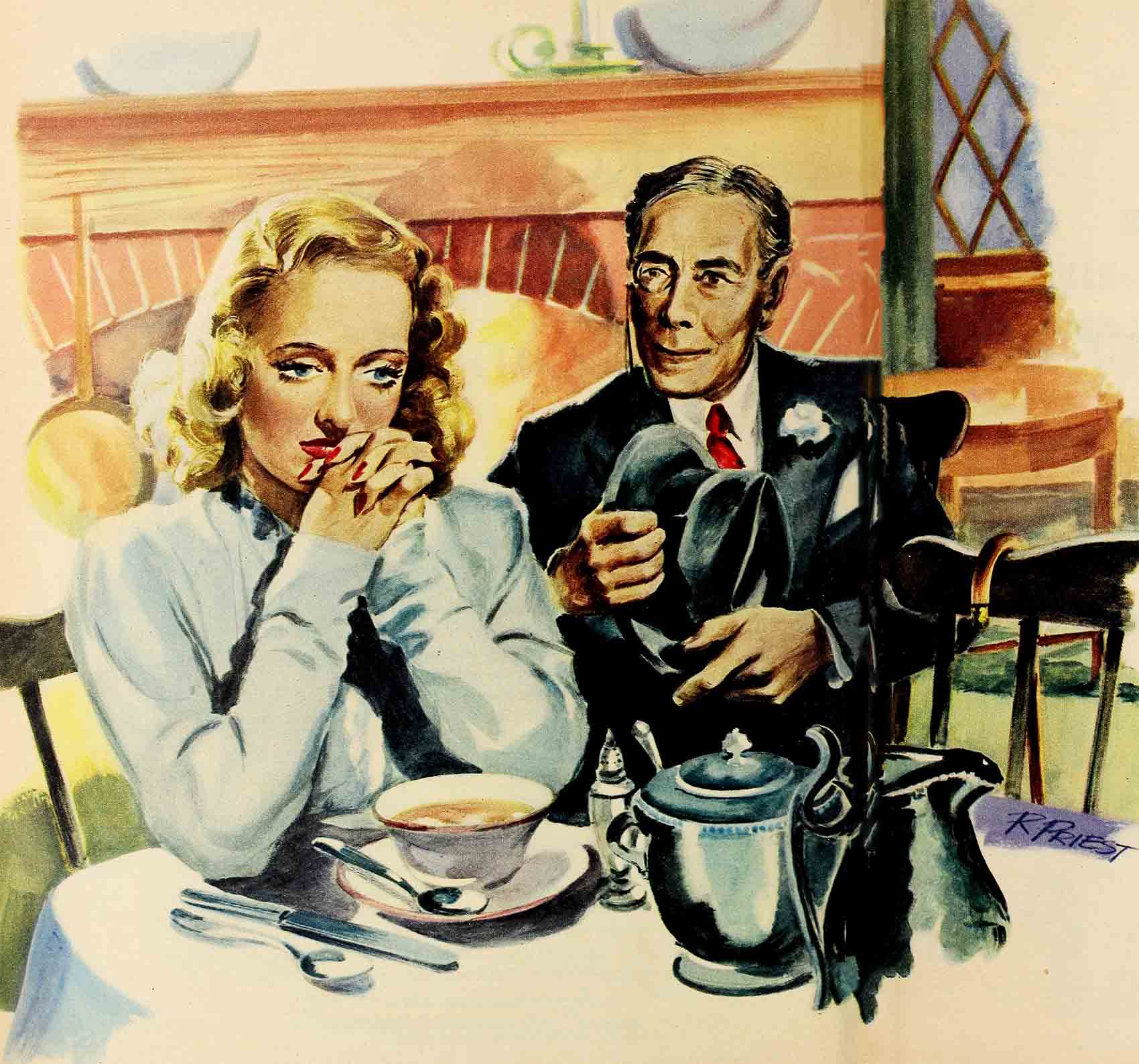

Mr. Arliss had come and gone. They’d had their tea in a corner of the rambly living-room, and you wouldn’t have known Bette for the same girl. Outwardly nothing had changed, yet the whole world looked different.

“He’s coming,” Bette had thought, “to cheer me up.”

That was part of it maybe, but not the principal part. He came because he was a man of imagination, and knew she’d be desperate and guessed what form her desperation would take. Because he was old and seasoned, because she was young and proud and mutinous. Because the years had taught him a lesson he wanted to pass on.

“There are just two things you can do,” he told her. “Continue your rebellion or take your medicine. In the first case, you’ll go off somewhere and hide. That’s a child’s trick. You’re grown up, my dear.”

“You don’t mean go back and give up? Oh, I couldn’t do that!”

“What’s to prevent? All it requires is courage,” he observed blandly, “and you’ve plenty of that.”

“Not enough, I’m afraid. They could put me through purgatory.”

“I don’t think they will. But whatever they put you through, you must accept it. Because, either you work in California, or you never work in this industry again. One road or the other, you’ve got to choose.”

She heaved a miserable sigh. “That’s the trouble. I can’t face either.”

“Face one, and you’ll find half the trouble’s gone. You’ve carried the fight to the last gasp and you’ve lost. Maybe the fighting was important, but the outcome isn’t. All your thinking is poisoned by the notion that there’s something shameful about defeat. Win or lose, nothing matters but the spirit in which you take one or the other. Kipling said it this way: ‘If you can meet with triumph or disaster, and treat those two impostors just the same—’ Impostors, because they have no value in themselves, only in what they do to you. If you refuse to let defeat make you bitter, it’s powerless against you. Rise above it, and you’ll be a bigger person than if you were going back at the head of a parade.”

Long before tea was over, the blinders had dropped off Bette’s eyes. George Arliss pierced the confusion of her mind with light, re-established her values and gave her a measure of peace.

His judgment proved sound on all scores. Once she knew what she had to do, half the load was lifted. And to run ahead of the story a little, he was right about the studio, too. They were wonderful. The ordeal by humiliation never took place except in Bette’s mind. The trial was never mentioned. Mr. Warner greeted her, said “Let’s forget it,” and put her into a memorable picture called Marked Woman. From then on, Bette’s star zoomed upward.

None of which Bette could foresee that day. But bidding her old friend goodbye, she held his hand between hers. “This is Thanksgiving Day in my country, Mr. Arliss. You’ll never know how much I have to thank you for.”

That night she was ravenous,’ causing the waitress who’d watched her pick at her food for weeks, to beam. “I’m glad you enjoyed your dinner, Miss Davis.”

“I did indeed.” A funny little smile came over her face. “But I’ll tell you a secret. You think that was beef and Yorkshire pudding you gave me? It wasn’t at all. It was turkey and cranberry sauce and the most delicious mince pie I ever tasted.”

THE END

—BY IDA ZEITLIN

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE DECEMBER 1947