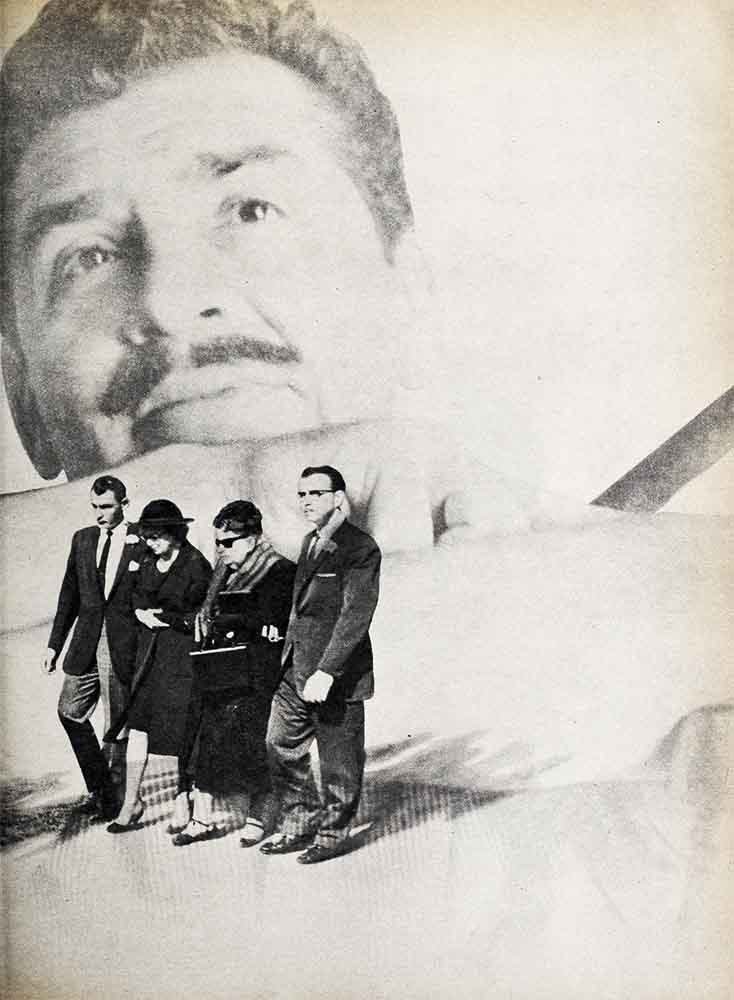

Ernie Kovacs, Farewell…

The laughter and the gaiety at Billy Wilder’s house was genuine and abundant. This was a gathering of close and dear friends to celebrate the adoption of a little boy by Ruth and Milton Berle. No one could foresee, amid all this joy and delightful comaraderie, the sudden and shocking tragedy ahead—tragedy which would strike without warning and take the life of one of the guests—take it so cruelly and swiftly that it would cast a pall over Hollywood darker than the blackest night. The party was a huge success and kept getting better as the evening wore on. Ernie Kovacs, master of zany comedy and outlandish vignettes, Milton Berle, Danny Kaye and George Burns, were all at Wilder’s Wilshire Terrace apartment in Beverly Hills that night, the night of Friday, January 12, 1962. There were others, too, like Lucille Ball and her husband Gary Morton; the Dean Martins, Kirk Douglases, actor-producer Martin Gabel and Yves Montand.

Everyone had arrived early—that is, everyone but Ernie Kovacs. He was detained at the studio and showed up late. His wife, Edie Adams, had driven to the party by herself in her white Corvair station wagon. The festivities were in full swing when the bushy-mustached, heavybrowed Ernie pulled up front in his big Rolls-Royce limousine.

As he walked into the merriment, the guests all at once turned and cheered big, lovable Ernie. He stood at the door a moment, raised his hand to his mouth to remove the ever-present cigar that seemed to be as much a part of his face as his nose, and blew a puff of smoke into the room. His clothes looked damp.

“Greetings, friends,” he chortled, “I encountered a bit of dew on the way here.”

What Ernie meant was that the weather was miserable. It had been raining continuously and the streets were dangerously slippery.

Ernie’s dark eyes scanned the room until they settled on his tall, blond wife who was on a settee next to Ruth Berle. Ernie, dressed in sports clothes with a jacket whose buttons were made of gold coins, crossed swiftly through the crowd, nodding and saying hello as he went. When he reached Edie, he bent forward to kiss her on the cheek.

The party continued. The midnight hour was soon left behind as the morning of a new day began. It was a few minutes past 1 A.M. when Ernie and Edie decided to leave for home.

Ernie, who had been on the highway not long before, knew how slick the rain had made the streets.

“Edie,” he said, “you take the Rolls home—I’ll drive the station wagon. You’ll be safer in the big car. It’s awfully bad driving in the mess out there.”

Edie consented to the exchange and, after bidding adieu to the other guests, went out to Ernie’s Rolls and drove to their huge $600,000 hilltop mansion in Coldwater Canyon. It was a ten-minute ride through Beverly Hills from the Wilders’ place.

Ernie got behind the wheel of the small station wagon. and took off after his wife, going eastward along Santa Monica Boulevard. Ernie had no qualms about driving a small car, nor had Edie any apprehension in letting him do so when he wanted. Ernie loved small, fast cars—the faster the better.

The Rolls, of course, was his favorite because it represented a status for which Ernie had struggled determinedly through long, rugged years.

Ernie loved status symbols—his Rolls; his big seventeen-room mansion with his special blacktop turntable resembling a railroad roundhouse that whisked visitors’ cars around on the hilly driveway so that they faced the Street, his one-dollar stogies—he smoked eighteen to twenty a day and wracked up an annual cigar bill of more than $7,500.

But that was Ernie. Those possessions were symbols of achievement for the comedian-actor who had spanned the divide between a four-dollar-a-week furnished room off Times Square to the fabulous heights of stardom.

Yes, he had made it, and made it in a big way.

And the big way was the way Ernie wanted to live it, now that he had the ways and means to carry it off.

Friendship—a treasured word

But through his rise to fame and riches, Ernie treasured one thing above all else—friendships. Few actors knew the meaning of congeniality the way Ernie knew m and practiced it. His home was always being visited by the biggest names in show business, people who admired him as a true, loyal, devoted friend.

But Kovacs’ chums were not only “names.” The man in the Street regarded Ernie as a friend, too.

For instance, there was Louis Sorgi, the security officer of the Beverly Hilton Hotel in Beverly Hills. He knew Ernie Kovacs for he had seen the comic in the hotel many times. And he liked Ernie Kovacs.

That was why Sorgi could not believe his ears, why he stared incredulously at the young bellhop who ran up to him in the hotel lobby at 1:20 o’clock that dreary, rainswept morning of January 13th and gasped:

“There’s been an accident down the Street on Santa Monica, right near Wilshire Boulevard . . . it’s awful . . . a station wagon wrapped around a pole . . . and, and … it looks like Ernie Kovacs . . . he looks dead . . . I tried to stop cars to get help but nobody would stop . . . we’ve got to get help to him . . .”

Sorgi, trained for emergency situations, responded swiftly despite his instinctive hesitancy to believe the worst for the beloved comedian he had known and liked so well.

While the bellhop phoned police, Sorgi raced out of the hotel to the scene of the accident, about one hundred yards away. As he reached the crash, Sorgi saw that the bellhop had not over-dramatized the tragedy by any means.

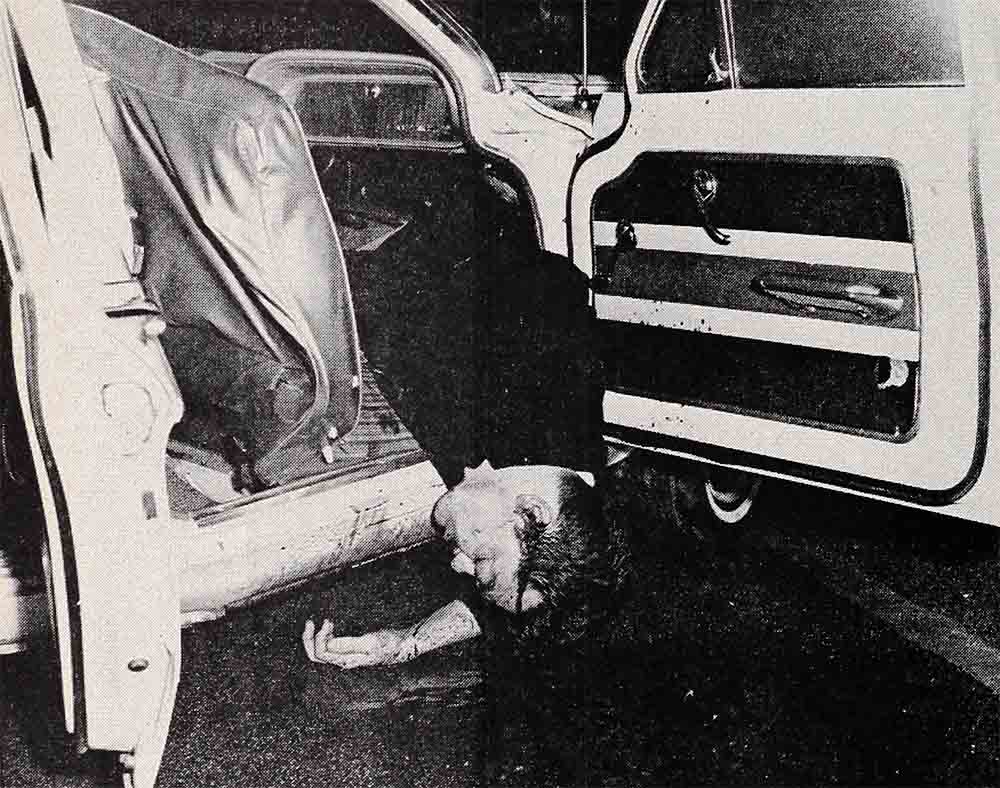

The car actually was bent like a boomerang around the thick wooden pole, crushed like an eggshell at the point of impact on the driver’s side. The right side of the car was split apart at the chassis by the force of the collision, and the doors had both sprung open wide. Evidently the car had gone out of control on the slippery road, jumped a curb, and crashed! Into the pole—broadside.

Sorgi walked to the right of the car and cast a wary eye at the front seat. It was a sight he hoped he wouldn’t see. But it was just as he’d been told—Ernie Kovacs was lying there across the seat, his body jammed inside the car, one leg under the seat, the other touching the crushed door on the driver’s side. His head was dangling over the seat.

Not more than three feet away, lying in the rain-soaked street, was Ernie’s familiar symbol—his cigar.

Within minutes, police cars and an ambulance arrived. The ambulance physician examined the body and shook his head. He confirmed what the bellboy and the security officer had suspected.

“Dead on arrival,” the doctor reported to a police official.

A policeman left for the Kovacs home. Before he arrived there, the phone rang. The caller was a reporter who asked where Ernie had been that evening.

“Why?” asked Edie.

“Because he was in an accident,” the reporter replied.

“I don’t believe it,” cried Edie in astonishment. “Why, I just left him. We were at a party at Billy Wilder’s place . . . ”

The reporter did not tell Edie the terrible news that Ernie was dead. Nor did the policeman who arrived at the house minutes later.

“It’s a serious accident,” he said. “Very serious . . .”

Edie learned the tragic, heart-rending news from Billy and Audrey Wilder, who came to the house a short while later with Ernie’s two closest friends, Jack Lemmon and Buddy Hackett. “I don’t believe it! I don’t believe it!” Edie wept.

She pleaded to go to the morgue to see. Ernie, but everyone argued against it. Edie insisted but then, overwrought by the magnitude of the tragedy, she collapsed. The family physician gave her a sedative to ease her pain and put her to sleep.

Lemmon himself went to the Los Angeles County Morgue several hours later to make a positive identification of his friend. The coroner reported that Ernie suffered a fractured skull and ribs, a ruptured aorta—the large arterial trunk in the heart—and other injuries. Death was instantaneous—mercifully, he had died without suffering. The one, only blessing.

A gentle, quiet man

Ernie Kovacs, the gentle, quiet man whose own brand of unique humor and antics had amused and delighted millions of fans, was dead. And now the laughter had turned to tears.

When Edie awoke, she hardly noticed the bright morning sun of the new day. As she sat in tearful mourning, her thoughts certainly were filled with the burning memories of her big, good-natured husband with whom she had shared life since they were married in Mexico in 1954.

Together they had lived in happiness beyond anything either had known before. Together they had become parents of a daughter, Mia Susan, now two; together they shared the joys of raising the daughters of Ernie’s first marriage, Betty, fifteen, and Kippie, thirteen. Now Edie thought about the older girls; she had to be the one to tell them their daddy would not be with them anymore. Ernie’s mother was there, too. She was fast asleep when the tragedy happened . . . but she knew about it now.

How empty Edie’s world. How far it must have been from the sumptuous seventeen-room Central Park West apartment in New York in which Ernie and Edie had lived in those early days when Edie was a singer and comedienne who had just made a hit appearance on Arthur Godfrey’s televised “Talent Scouts” show.

Could Edie forget the nights Ernie sat up creating routines—routines for Edie— whom he put on his zany TV show? And could she forget that while she slept, Ernie toiled over the script until finally she would waken and see Ernie gazing down at her with his whimsical smile and furrowed forehead.

“You lie around in bed all morning until 6:30 before you stir,” he would chide her. Could Edie ever forget those moments?

Ernie and Edie were inseparable and their life together was a reflection of a joyful merry-go-round which brought them a new brass ring of happiness each day.

“I never want to leave home,” Ernie had told an interviewer not many days previously. “I never want to leave my wife, my kids. I love my home.”

But even more recently, only the night before at the party, Edie herself had overheard Ernie talking with Jeanne Martin, Dean’s wife.

“I’m going to live forever and maybe beyond,” he said. “I’ve found the secret to a long life. All it takes is three steam baths a day, lots of good brandy, about twenty cigars, and work all night.”

Edie had tried to subdue her smile when Jeanne retorted, “If you don’t cut out all those steam baths your heart will give out on you some day.”

Ernie gave Jeanne his inimitable Cyclops-like stare.

“Look, kid,” he said, “this is the only life I’ve got and I want to live it the way I like it. If I go, I want it to be my way. Besides, those steam baths don’t hurt me. I can go day and night.”

Ernie was so certain, so positive that nothing could hurt him.

Edie knew Ernie was born January 23, 1919 in Trenton, New Jersey. But she didn’t know him when he had a close brush with death back in 1939. He was an unknown actor then, trying to ascend the pinnacle that Fate had ordained he’d ultimately reach. He had come up the hard way, making his first appearance in public as a tenor in class operettas at Trenton’s Central High School. His voice and acting ability in a version of “The Pirates of Penzance” were largely responsible for the scholarship offers he received from dramatic and music institutions.

But Ernie, the son of a Hungarian immigrant who ran a tavern in Trenton, decided after graduation to go directly into stock company theater. He formed his own troupe and played Trenton, Bordentown, and nearby Philadelphia. Then he moved on, still an unknown acting hopeful, into summer stock on Long Island and obscure towns in New England. Then came that first brush with death, in Brattleboro, Vermont, when Ernie came down with pleurisy and double pneumonia.

Edie had heard the story a hundred times if she heard it once, and now in her grief as she mourned Ernie’s death she couldn’t help but recall how he laughed whenever he retold it:

“I was so broke I had to settle for the charity ward at the hospital. It looked after a while that I would be a permanent resident. For a year and a half I had a temperature of 102°.

“I watched other patients die of the same ailment. They got thinner and thinner until they just died. I wasn’t going to let it happen to me. I ate everything.

“I finally decided the treatment was worse than the illness and walked out. The doctors said I wouldn’t live three months. They’re still kinda angry because I didn’t die up to their predictions.”

His mother, Mary, nursed Ernie back to health with home cooking and he went on—in spite of the prophecy—to a successful career as a disc jockey for radio stations in Trenton and Philadelphia. In 1948. he became a special events director of WTTM in Trenton and also wrote a newspaper column for the Trentonian.

Even then he was zany. He broadcast from dirigibles, planes, boats, moving cranes—everywhere, it seemed, except the radio studio. But his perpetual cigar, his black mustache, his leering smile and his special brand of humor which some critics believe was ahead of its time, brought Ernie a television assignment in Philadelphia and, in 1952, in New York.

The next ten years are the story of a Horatio Alger climb to success—on the “Tonight” show on NBC, before Jack Paar took it over; then other programs of his own which earned him the reputation as one of TV’s most inventive comics.

Edie remembered those moments now in her hour of sorrow for she was a part of them, a part of those devil-may-care moments when Ernie would let the camera move in on his nose for a full minute’s close-up of a twitching Kovacs nostril.

Even Edie had trouble sometimes figuring out Ernie’s brand of humor. It was improbable and illogical—but funny. And while Ernie went on to greater fame in TV, not only as a funnyman but a director and producer, Edie made her own mark on the Broadway stage.

Edie also shared Ernie’s great moment when Hollywood beckoned.

Through several pictures, Columbia typed Ernie as a comic villain, usually a stiff army captain. But he fought typecasting, especially fat captains. So he went on a vigorous diet.

“I lost forty pounds for ‘Our Man in Havana,’ ” Ernie said not long ago. “It showed I can play thin captains, too.”

But Ernie’s zest for good food always gave him trouble at the scales. He was a big man to begin with—six feet two and a robust two hundred pounds plus. And his love for good food was never better illustrated than when he hired a cook at a salary of $1,000 a month.

“She is so great that I eat home every night now,” he would say. “I’m afraid if I don’t that I’ll miss something.”

Indeed. Ernie did not want to miss much.

He enjoyed life, lived it to the hilt. He indulged his tremendous zest for good living by having only the best of everything—whether or not he really could afford it. The house cost Ernie only $100.000 when he bought it, but his mania for the ultimate in lavish living resulted in expenditures of $500.000 to provide the things he wanted.

His den was uniquely Ernie Kovacs in taste and decor—there were rows and rows of rare wines and liquors, a sprawling library of fine books, a suit of armor once worn by Douglas Fairbanks, Sr. in a silent movie, a brass leopard from India and many other fine and expensive objects. The most remarkable was an artificial waterfall in a rustic setting.

Above all, Ernie’s greatest dedication was to Edie and the children. He loved them and they enjoyed life in a manner that was rare in Hollywood—they enjoyed it together.

Hollywood and the world have been saddened by the shocking death of Ernie Kovacs, and he will be missed greatly. But no heart is filled so heavily with grief as is Edie’s, for only she can know the utter desolation of having lost the only man in her life.

Perhaps, in her suffering and complete prostration in the hours after Ernie’s simple funeral, Edie may have thought what might have happened if she had not traded cars with Ernie that night. Fate already had played a hand for Yves Montand, as it was learned later. On the way out from the party, Ernie had offered to give Yves a lift home. But he had already accepted a ride with Milton and Ruth Berle.

To Ernie, every minute of his life since his close call with death in 1939 was a gift. “After what happened to me, I figure I’m living on velvet,” he would say.

We hope Edie will find solace in her great bereavement in knowing that Ernie Kovacs will not be forgotten by those who knew him. They will remember him for the gentle, thoughtful person, brilliant performer, good husband and loving parent that he was. . . . Ernie, farewell . . .

—GEORGE CAMBER

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE APRIL 1962