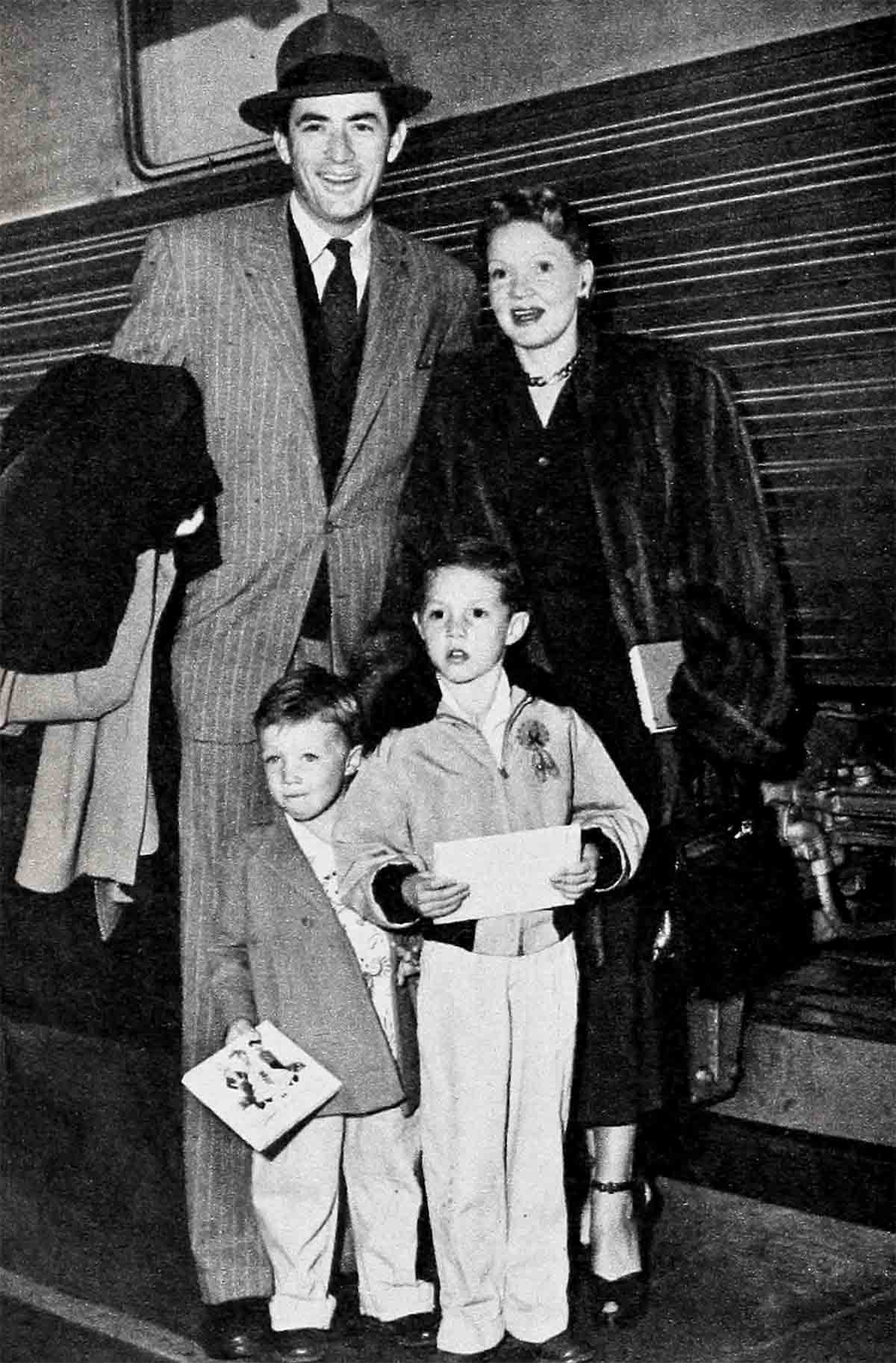

A Tobey & A Peck—Gregory Peck & Greta Kukkonen

Greta Konen and Gregory Peck were at a World Series baseball game when they decided to get married. “I’ll call Tobe,” said Greg, but Tobe wasn’t in. After the ceremony they stopped by at Greg’s place to pick up his things. Every few minutes the groom poked his long neck through the window and presently spied the man he was waiting for. “Hey, Ken!”

The rugged redhead ambling down the street below looked up. Peck’s grin broadened. “Hi! I just got married—”

A year ago Kenneth Tobey met Penny Parker, who was singing with a band. “You sing so pretty,” he told her. Penny’s his wife now. They had planned to be married last August at La Jolla, with Greg as best man. Instead, they found the perfect apartment. “Take it or leave it,” said the landlord. Since they couldn’t support three apartments—Pen’s, Ken’s and this third one—they took it and flew to Arizona, where you don’t have to wait.

That’s the story of how Gregory Peck wasn’t Kenneth Tobey’s best man, and Kenneth wasn’t his.

Back in the lean days, Tobey’s wedding gift to the Pecks was a Silex. Theirs to Penny and him was sterling silver. “But I guess in each case,” says Ken, “the gift meant the same thing.”

What it meant was a solid friendship, short on words, long on understanding. The paths of the two men met, ran close, parted and met again without disturbing anything fundamental. While Peck’s professional star zoomed to the top of movie heaven and stayed there, Tobey floundered in one legit flop after another. Not till eight years after his friend’s spectacular rise did. Tobey come crashing through in “The Thing,” hitting Photoplay’s popularity poll among others. When he got the part, it was Peck whom he called first. “I think he wanted it for me as much as he wanted his own career for himself.”

Trying to analyze Peck’s special gift for friendship, Tobey takes time to pick his words. “It’s a kind of father confessor quality. Yet—maybe that gives the wrong impression, too. Because there’s nothing detached or holy about him. But he listens—not just with his ears but with all of him. And somehow, when things get rough, he knows how to put his finger on the sore spot and apply just the right balm. Maybe fifteen minutes later you’ll be thinking, ‘What am I feeling so good about? I’ve still got the same problems—’Nevertheless, the warmth remains.”

Once, after a protracted dry spell, Tobey lost a very good part at Metro. The contracts were drawn up. He came bouncing in to sign, and went jolting out with a sickening sound in his ears. “Sorry, we’ll have to use someone else.” Morose was too cheerful a word for him as he bumped into Peck and gave him the sour news.

Greg’s eyes studied him. “You’ve got a lot of guts,” he said, and that’s all he said. It was enough. It gave his friend the sense that someone was with him, someone who understood, and his burden lost half its weight. “Maybe once in a blue moon,” he says, “I’ve been able to do the same kind of thing for him. Maybe not. He’s a hard person to do anything for—reluctant to accept help, ready to give it—”

Ken was a big help at their first meeting. Called Greg a lousy actor or words to that effect. At the University of California, they joined the Thalians, a theatre group. Greg was on stage in a dramatization of “Moby Dick”; Ken was in the audience. Greg, a pre-med student, liked to act for the hell of it. Ken, studying law, was out to acquire aplomb, nonchalance and ease. “Commodities,” he’ll tell you cheerfully, “that still elude me.”

The audience was asked to criticize the players. Ken would have felt lots better with his mouth shut, but that was no way to practice public speaking. Quaking, he rose, fixed glassy eyes on the stringbean with the face of a Near East prince, and in a few ill-chosen words condemned his performance as hammy. The victim took it with composure. Grinned at Ken in passing. “You sure gave me a roasting.”

So they started saying hello. Soon the hellos grew more enthusiastic. Ken landed a fat line in a musical. “Peaches, I want my dinner.” This struck Greg as so uproarious that he still quotes it. They cast Peck as Mat in “Anna Christie.” Tobey thought he did a good job and told him so. Their co-workers rated them as follows: “The movies’ll take Greg on account of his looks, but he’ll never be an actor. Tobey won’t be an actor or any good for the movies.”

As if to kick this appraisal straight in the teeth, both boys snagged scholarships for the Neighborhood Playhouse in New York. Dazzled, they chucked law and medicine to the wolves. Greg entered the Playhouse on time. Ken arrived late, detained by the need of earning some dough at the San Francisco Fair. This accident introduced a new feeling into what had been a casual, if pleasant, relationship. Lonely as a barb in a frat house, Ken braced himself for the cool stares of the élite. “Hello, Tobey,” said a quiet voice, welcoming, warm—and there stood his fellow Californian.

With interests, tastes and poverty in common, they joined forces. In a way, they complemented each other. Both were self-conscious, but their self-consciousness took different forms. Greg withdrew into himself. Ken found release in a kind of boisterous humor which amused the other. Economically, they were one, splitting whatever funds came their way. Ken bought Greg his first zombie, Greg bought Ken the first New York steak he ever set tooth to. Tobey Senior, acting as custodian of his son’s shekels, doled them cut by request at the rate of thirty-five dollars every two weeks. So much they were sure of while it lasted. Greg did some modeling. No collar-ad stuff, though. Always something rugged like an engineer in overalls. When he got twenty-five bucks, he’d blow it on anyone who needed a meal. Inconsistently enough, it was Greg, the shy one, who promoted eating money when they went broke on Saturday afternoons. “Think we could touch Miss Lewisohn for a loan?”

“Not me, brother—”

“All right then, I will. But you’ve got to come along for moral support—”

Irene Lewisohn was head of the Playhouse, a lady of dignity, charm and reserve. Fascinated, Ken would watch his partner wind himself up like a electric gadget till the words came blurting out. “Miss Lewisohn, may I borrow five dollars?”

“Why—yes—” Then she’d look at him. “Yes, Gregory—” with the shade of hesitation gone, as if how could you let a guy like this go hungry.

Meantime they were lapping up New York—from concerts to subways, from the top gallery of the Metropolitan to a hill in the Bronx, where they borrowed sleds from a couple of kids and went coasting.

When Guthrie McClintic and Katharine Cornell were taking “The Doctor’s Dilemma” on tour, they gave Greg the role of the art dealer. It was one of those miracles that can’t happen but does—Shaw, Cornell, McClintic, magic names in the theatre and Peck in the midst of them.

Tobey recalls what happened during rehearsals. Greg was the novice, the greenhorn, naturally anxious to do well, anxious to be liked. One day he came home looking bothered. “What’s wrong with me, Tobe? Either I’ve got no humor or I’m dumb. These guys in the cast—Ralph Forbes, Cecil Humphreys—swell people, friendly, been wonderful to me. Only they’ve got so much in common—background, experience, tradition. So they talk and laugh their heads off while I sit like a goon and can’t think of a word to say.”

After cutting it nineteen ways, Greg came up with his own answer. “What’s wrong with me is, I’m no conversationalist. Okay. When I’ve got something to say, I’ll say it. Otherwise, I’ll keep my trap shut. There’s no percentage in trying to be what you’re not.” He talks more easily nowadays, says Ken. But except in the world of make-believe, he’s never tried to be anything but himself.

Both men realized with a touch of sadness that Greg’s departure marked the end of a chapter. His bags stood at the door. “Well, s’long, Tobe.” Then, a very casual afterthought: “Oh, by the way, you got any dough?”

“Sure,” said the other, fingering the nickel in his pocket. Keeping only enough for cabfare, Greg shoved some bills at him, picked up the bags and was gone.

His return was memorable, too. Knowing that Greg’d met a girl named Greta who was something special, Ken elected himself a welcoming committee of one. Armed with kazoo, trumpet, and toy drum, he descended on Grand Central, spotted Greg’s head above the crowd and went into action on his noisemakers. It would have been fine except that, along with Greg and the pretty blonde at his side, walked Cornell and McClintic—two people Ken would have liked to impress, though not as a clown. Turning green, he stuffed the brass in his pockets and tried to pretend that the drum ’round his neck wasn’t there. Greta stoutly maintained that the effect was charming, and Ken pledged her his loyal allegiance on the spot.

In a play called “Sons and Soldiers,” the friends appeared together. on Broadway for the first and only time. It was a nice experience, if brief. They closed after three weeks and again they parted—this time with more finality. Proving the Thalians true prophets in one respect, Hollywood the golden sent for Mr. Peck.

The cliché runs that Hollywood changes people. Tobey thinks it ain’t necessarily so. “Friendships are more often spoiled by the friend left behind who carries a chip on his shoulder through envy, oversensitiveness or what-have-you. I speak from first-hand experience. Greg didn’t change, I did—or started to—”

He was working, but not steadily. When Greg came to town, they’d go out. For every drink and dinner Greg bought, Tobe matched him. The other’s protests hit solid bone, for Ken had grown self-conscious about money as he’d never been when Greg was in the same boat. Resentments began to simmer—so deep he was hardly aware of them till one day his friend plucked them into the open.

“I know how you feel, Tobe. It’s human. In your place, I’d feel the same way. And in my place, I hope you’d say the, same things to me. Friendship has no room for this kind of competition. Each one should do what he can. In the old days we’d have taken sharing for granted. What’s different about now?”

In Greg nothing was different. Gently he had put his finger on the sore spot, and Tobey was healed.

Confident of Tobey’s quality as an actor, Peck’s idea was that he and the movies should get together. Ken was more than agreeable. In ’46 he came out on a courting visit that netted him a couple of indifferent stares, so back he went to play in “Joan of Lorraine.” The spring of 748 brought a wire from Peck. “La Jolla starts soon. If you want to work, get out here.” Funds being at ebb, he caught a cheap plane. Greta met him at the airport. “You’re staying with us.”

He stayed seven months—a notion that would have staggered him in advance. But when the La Jolla season closed, Greg said: “Why don’t you stick it out for a while? Maybe something’ll break.” Greta said: “Please, Ken. You know we have plenty of room.” Without piling it on, they made him feel wanted and welcome.

The first small toehold came in “Twelve O’clock High.” Greg was responsible only up to a point. No star, however big, casts his own pictures and his influence is narrowly limited. If you’re Peck, you don’t overstep those limits. If you’re Tobey, you don’t want them overstepped. Greg introduced him to the casting director at Fox, and Ken began hearing about this picture. For the first time he made a specific request. “I think if I met Henry King, I might sell myself to him: Could that be arranged?”

Greg took him to the director. “I’d like you to meet a friend of mine,” he said, “who’s a good actor,” and left.

Tobey did the rest. Before the interview ended, he was King’s boy. “I wish you’d come sooner. There’s only a bit left now—the sentry at the gate.”

This scene was the first in the picture. It impressed other people with the truth of Peck’s unadorned statement that his friend was a good actor. As more jobs came along, he felt it was time to stop being a guest and moved out to a hotel. The day he left, Greg said, “You’ll be Tobe,” and gave him a check. “Look;” he added before the other could register, “when one of our cars went on the blink, you got up at four and waited for traffic to start, so you could bum a ride. That’s no good. If you’re going to work in this town, you need transportation.”

“I feel like a cadger.”

“You’d do it for me, wouldn’t you?”

With a contract at RKO, Tobey’s repaying him now. The contract grew out of “The Thing.” “The Thing” grew out of “I Was a Male War Bride,” Howard Hawks directing. “Some day,” said Hawks, “I’m going to make a picture with unknowns. If you’re still unknown, Ken, I’ll want you as the lead.”

Pleasant words that might mean anything or nothing. Two years slipped by. Then one day the phone rang. Mr. Hawks’ secretary calling. An hour later Hawks handed Tobey a script. “We’ll have to make a test. That’s a Howard Hughes rule. But as far as I’m concerned, you’re in.”

“The Thing” bounced Tobey, with his easy performance, his attractive blend of humor and strength, out of obscurity into public favor. They signed him to a long-termer. Not the least rewarding moment of those thrill-packed days was the voice of his friend Greg on the wire: “Told you you’d make it.”

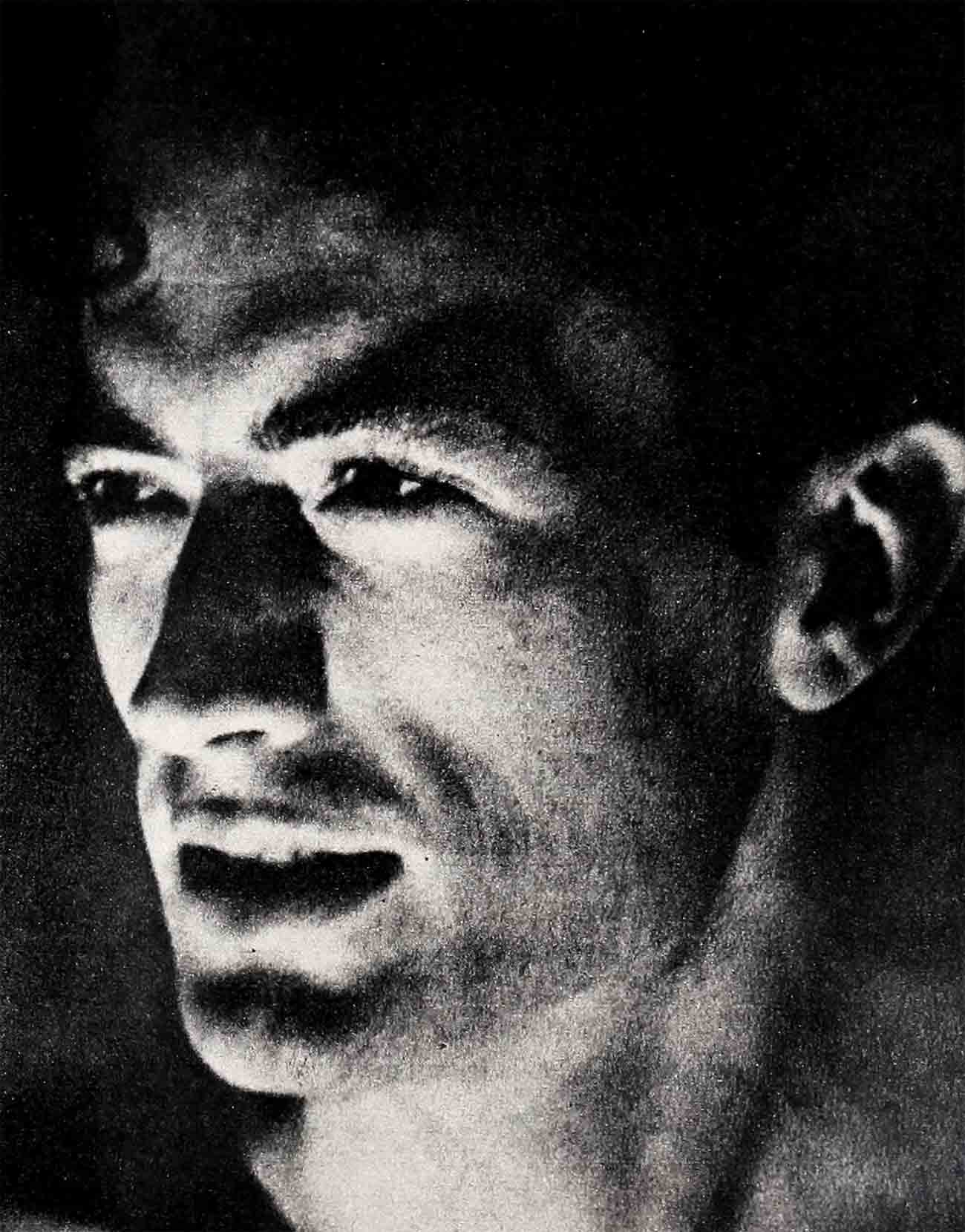

For a Tobey’s-eye view of the Peck of today, let Ken do the talking:

“Essentially, he’s the fellow I met twelve years ago—simple, direct, with a courtesy that comes as natural as breathing. More mature, of course. And harder-working. But whatever he does, he throws himself into. Even canasta. Plays a reckless game for pennies, but hates to lose.

“But I guess it’s his family life that tells most about him. They say you can judge by kids what the parents are like. If so, these parents, Greg and Greta, can take a bow because the kids are great. Jonathan’s seven—dark, slender, serious. Stephen’s a sensitive five-year-old and one of my best friends. Carey Paul’s still a baby, blond like Stephen and his mother. They’ve all got Greg’s courtesy, Greta’s enthusiasm and their’ own charm.

“I’ve heard Greg talk about what he wants for them. For the future, to work at whatever they want. For now, love and security and some of the advantages he can afford to give them. But not enough to dull them to what’s more important.

“If Jonathan wants to ride, he has to earn that right by keeping his room straight. Riding he loves. Swimming he used to hate. When the swimming teacher came, he’d hide under the bed. Greg neither forced nor shamed him into the pool—just eased him into it with affection. I wouldn’t call him demonstrative with the kids. He maybe doesn’t say ‘I love you’ as much as I would. But it comes across just as plain without his saying it. Or plainer. He swims and rides with ’em, gets on the floor and wrestles with ’em.

“He never brushes them off. Jonathan brings his paintings home from school. Every kid brings his paintings home from school. We make a big fuss over the first two or three, then we lose interest. Greg spends as much time on the twentieth as on the first. He gives their trivia the same concentrated attention as his own affairs—offers honest opinions, makes them feel they’re somebody—which they are.”

Tobey paused reflectively. “If there’s one quality that sticks out in Greg, it’s his fierce regard for the individual. Humans really matter to him as humans. Your dignity is as safe with him as his own.

“To my mind,” his friend concluded, “that’s the measure of a man—”

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE APRIL 1952