Why Joe Let Her Go!—Marilyn Monroe

Just 263 days after Marilyn Monroe and Joe Di Maggio were married in San Francisco, Marilyn, through her lawyer, filed for divorce in Santa Monica, charging mental cruelty.

Hours later, those who had followed their story were asking, “Why? What really happened? We thought this was one of the happiest marriages in Hollywood.”

There was disillusion, disenchantment and disapproval. And there were plenty of answers from those who had been misleading the public for months with super-saccharine accounts of this supposedly idyllic marriage.

The reasons advanced for Marilyn’s marital breakup were that Joe was jealous of Hal Schaefer, Marilyn’s voice coach; that Joe was jealous of Natasha Lytess, Marilyn’s dramatics coach; that Joe was jealous of the 20th Century-Fox publicity staff; that Joe was jealous of Hugh French, Charlie Feldman, and several other agents who handle Marilyn; that Joe was jealous of the men, some extremely prominent, in Marilyn’s past; that there was a conflict of careers.

In short, Joe Di Maggio has been made the “heavy” in this divorce. That is unfair and not in accord with the facts.

There is no “heavy” in this breakup. Joe and Marilyn are both to blame. When each needed the other down. They talked one way about their marriage, but they did the opposite. More important, they felt the opposite.

Marilyn kept saying, “In our marriage, Joe comes first. He’s the boss. We want children as soon as possible.”

Joe kept saying, Her career won’t interfere with our marriage, because we won’t let it.”

High-sounding words, good intentions—but how were they carried out?

A few minutes before Marilyn was married, she had phoned Harry Brand, publicity chief at her studio.

“Joe and I are ob the way to City Hall to get married,” she announced. “I promised to let you know. And I am.”

The significant part of this conversation is that it was directed at a studio employee who has been important in Marilyn’s career.

Any other girl would have phoned her mother, her uncle, her roommate, an old school friend. It is sad and pitiful that Marilyn had no one in the whole world she wanted to notify about one of the happiest events in her life. No one but Harry Brand. It was Harry who notified the rest of the world, and in this notification Joe Di Maggio encountered the first of his disillusionments.

Joe had wanted a quiet wedding. “Just for the family,” he said. He had planned everything with precision and meticulous care. He had spoken to Reno Barsocchini who manages the Di Maggio restaurant at Fisherman’s Wharf. He had called Judge Charles Peery, an old friend from the Municipal Court, and during lunch at the restaurant, he had asked the judge if he’d perform the ceremony “very quietly, very quickly, nothing fancy.”

You all know what happened. The wedding became a Roman holiday—photographers, flash bulbs, reporters, questions. Judge Peery had to clear everyone out of his chambers except the principals.

After the ceremony, the mob, clamoring and congratulating, closed in. Joe’s brother Tom and Lefty O’Doul, his old friend, had to form a flying wedge before the newlyweds could get out.

In the meantime, Marilyn’s studio made every attempt to find out where Joe and their blonde were going on their honeymoon. Joe refused to tell anyone. He was fed up with publicity.

Marilyn never has liked to disclose the exact location of her honeymoon retreat. If you ask her today where she and Joe spent the two happiest weeks of their marriage, she will say, “Idyllwild, a lovely place in the mountains about fifty miles from Palm Springs.” She will tell you about “the lovely cabin we had . . . long walks in the snow . . . people and. studios seemed so far away . . . Joe and I talked a lot . . . really got to know each other.” But she will not tell whose cabin it was.

It was her lawyer’s cabin, the lawyer who had helped her in her various studio negotiations. Always the studio, always the career, even though she was on suspension during the honeymoon.

There are many who say that if Marilyn had renounced her movie career after marrying Joe, they would still be living together today. This may be true, but would Joe Di Maggio ever have married Marilyn if she had not been a star?

If she had been plain Norma Jean Dougherty working in an aircraft factory, would he ever have given her a second look? Would he ever have seen her?

In all fairness to, Marilyn, she never intended to renounce her career.

In fact, if Joe had made career abandonment one requisite for marriage, Marilyn would have walked out on him. No matter what she may have said in other ecstatic moments, career is the primary force in Marilyn Monroe’s life. She has given her career everything she possesses.

Under the circumstances, who would ask her to abandon it? Certainly not Joe. He kidded himself into believing that coexistence was possible.

As Marilyn said in New York, “I’m just a pretty girl, but Joe is one of the all-time greats.”

She knew then that the marriage was coming apart and she tried desperately to stop the deterioration. But by then it was too late. Joe was convinced that he would have to play second fiddle to her profession. He knew in his soul that her career was everything to her.

This realization is what caused him such anguish while he was trying to cover the World Series for a Los Angeles syndicate.

One of the sportswriters who accompanied Joe to Cleveland and New York says, “Joe was tense and morose practically all the time. We were sure something was wrong with the marriage, and whenever we asked, he gave us the brush-off.

“After a while it got so that he would turn up at the ball park just a few minutes before the game got underway. He didn’t want to talk to anyone. The only one who really knew the inside story was George Solotaire, the New York ticket broker. Joe slept in George’s suite in New York, and George later flew out to Cleveland with Joe and listened to his tale of woe.

“Matter of fact, Joe wouldn’t even stay until the last game of the World Series was over. He left at the eighth inning, went back to his hotel, got his bag, and flew back to Marilyn.

“Stories that he received some anonymous letter telling him that Marilyn was on the loose and that he’d best hurry back are a bunch of junk in my opinion.

“Joe just happened to realize that in “Marilyn he didn’t have a wife, he had a kind of public utility. I think he became convinced of that when he saw the mobs in New York that gathered to watch her work on location.”

To date, Di Maggio has refused to discuss his private life in public, and it is doubtful if anyone, without his version, can reconstruct the immediate events that led to the marital rupture.

It is known that when Joe returned to the house on Palm Drive in Beverly Hills, a violent argument ensued.

Neighbors said that they could hear Joe and Marilyn screaming at each other.

“Lots of nights,” one neighbor recounted, “we could see Marilyn walking up and down the street alone. It was one A.M. or one-thirty am. One night I was parking my car and I saw her walking in the alley, and tears were streaming down her cheeks.

On Friday night, Marilyn had dinner at the home of Natasha Lytess, her dramatics coach. She cried all through dinner.

Natasha understands Marilyn. It is she who is primarily responsible for any acting ability Marilyn may demonstrate.

Marilyn confessed to her that she and Joe had been fighting for weeks.

Natasha knew it all along. When Marilyn, without notifying her, married Joe, Natasha, the widow of the German novelist, Bruno Frank, confided to a friend, “This marriage cannot last unless Marilyn gives up her career. She and Joe have nothing in common. This girl has an intellect. She hungers for the finer things in life; music, literature, art. The hunger is authentic and genuine and for years I have been trying to satisfy it.

“I know Di Maggio dislikes me, and I am sorry. But I am convinced this girl will not be satisfied lying on a sofa all evening watching cowboy movies on television. She is in the process of growing intellectually. This marriage is a classic example of mismating. It cannot and it will not succeed.”

On the night Marilyn confessed that she and Joe couldn’t make a go of it, maybe Natasha remembered her prophecy.

She tried to placate Marilyn, but Marilyn was inconsolable, almost hysterical with grief.

Joe just didn’t seem to understand her. He didn’t want to understand. These demands on her time—rehearsals, voice coaching, line-study, people she had to see were part of her work. It was expected of her. Worse yet, the marriage wasn’t getting any better. There was no adjustment, only quarrels, increasingly bitter quarrels.

While Marilyn was crying her heart out, Joe moved into the Hollywood Knickerbocker Hotel where he had stayed as a single man.

When he came back his mind was made up. He just couldn’t be straight man for a rising movie queen. He told Marilyn to file for divorce. Jerry Giesler, the famous divorce lawyer, took the case. Marilyn had talked to Giesler previously.

On Monday morning when Marilyn was due at the studio to continue work on The Seven Year Itch, she phoned Billy Wilder, the director, a little after eight.

“I—I won’t be able to come to work,” she sobbed.

“Why not?” Wilder asked.

“Joe and I have had a—” At this point Marilyn broke down.

“I can’t hear you,” Wilder pressed.

“Joe and I have split up,” the actress finally managed. “I don’t know when I’ll show up.”

Wilder called Harry Brand and the studio publicity chief made the announcement to the press, offering as the official reason “incompatibility resulting from the conflicting: demands of their careers.”

“What careers is the studio talking about?” one newsman asked. “There’s only one career and that’s Marilyn’s.”

Marilyn Monroe’s career is a big one, but it couldn’t support two people spiritually. Undoubtedly she recognized that point. But she did nothing about it.

Was there anything she could do?

According to one of Di Maggio’s relatives, “Sure, Marilyn could have done a lot, but it would’ve meant sacrifice. After she finished No Business Like Show Business, why did she have to go into Seven Year Itch?

“Why couldn’t she have gone off somewhere with Joe? I understand that Seven Year Itch cannot be released until 1956. What was the big hurry? Maybe she would’ve lost the part. So what? Maybe they would’ve had to make a new deal. Again, so what?

“A man is entitled to some of his wife’s time. All through Show Business, Marilyn came home tired and worn out. Joe is healthy and strong. I guess they started to quarrel even back then. I guess it’s all for the best. There is no sense in living in misery. Why re-hash all the trouble?”

On Wednesday, October 6, Joe Di Maggio packed his bags and left Marilyn and Hollywood. His friend Reno Barsocchini had driven down from San Francisco the night before, and as Joe left the Palm Drive residence, Reno took his bags and bounced them into the back seat.

Joe then walked out into a crowd of sixty newspapermen. “Hello, fellows,” he said. “I’ve got no comment.”

“But where are you going?”

“San Francisco,” Joe said lustily.

“You ever coming back. Home?”

Joe shook his head. “San Francisco,” he announced, “is my home. It’s always been my home.” He took one final look at the three-ring circus on what used to be his front lawn. Then he dashed to the car.

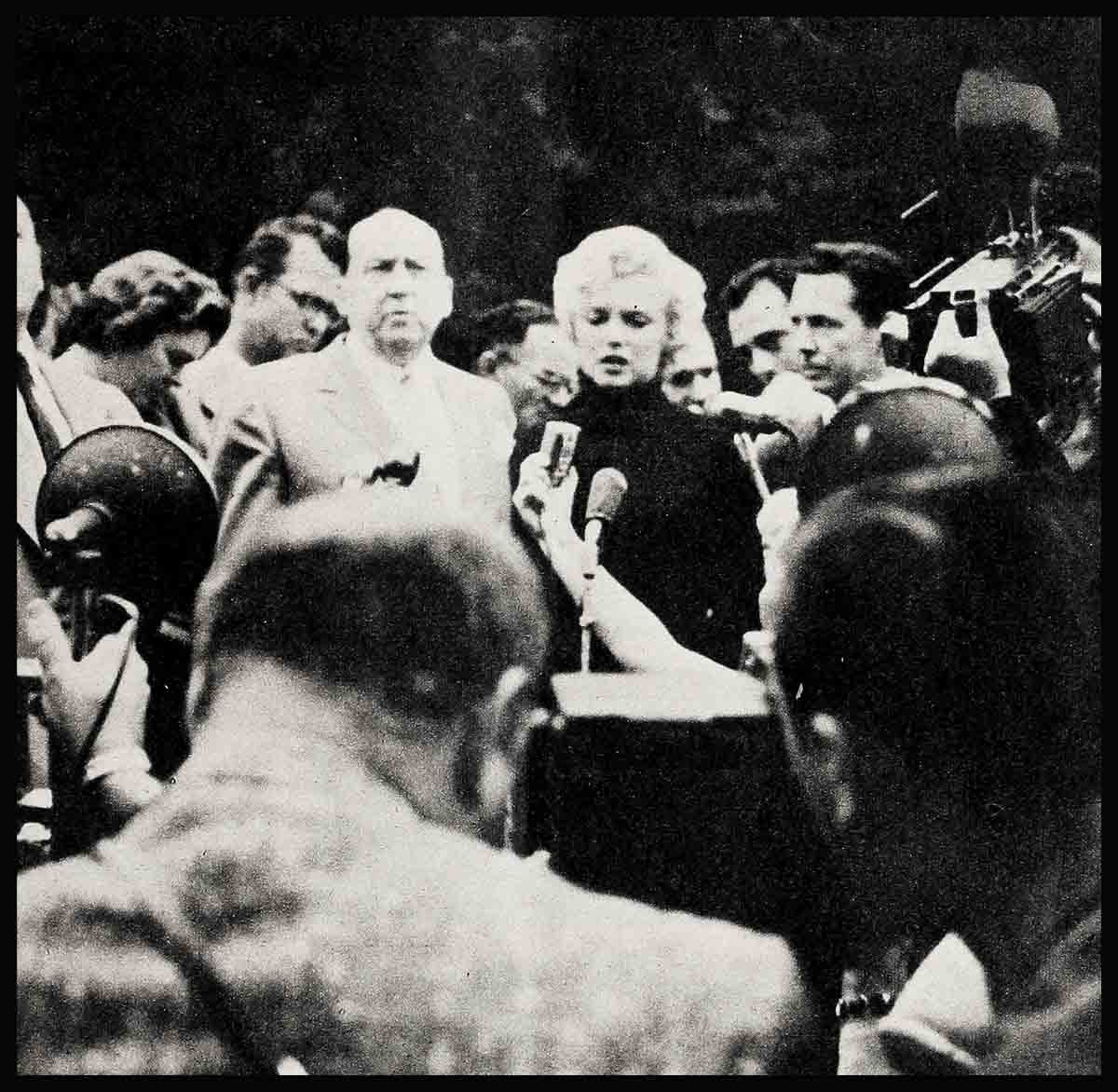

Approximately forty-five minutes later, Marilyn emerged from the same house, leaning on the arm of her attorney, Jerry Giesler. Reporters and cameramen swarmed down and Marilyn swayed uneasily as if she were about to faint. Her face, despite her heavy make-up, looked ashen and drawn. She was weeping as the newsreel cameras began to grind.

“Don’t ask her any questions,” Giesler said.

The reporters paid him no attention. One said, “What picture are you in?”

“I’m sorry,” Marilyn sobbed. “I can’t say anything.”

Giesler nodded. “Miss Monroe has nothing to say this morning,” he announced. “As her attorney,” he added, “this is what we can say is a conflict of careers. Anything else will be presented in the proper place at the proper time.”

Just why this press conference was called, no one can understand. Marilyn was certainly incapable of describing her domestic woes. She was so sick that when she reported to the studio, an hour later, she was sent home to bed.

Two days later, however, she was back in front of the studio cameras.

Attempts were made at questioning Marilyn’s psychoanalyst. He had treated her on and off for three years, but naturally he did not discuss his patient.

Some other psychiatrists talked. One claimed, “I doubt if Marilyn is capable of a lasting relationship with any man. When a woman becomes a big star, she has found a sure way to self-destruction.”

Said another, “In this case we have two people who are insecure, emotionally and intellectually. To have a workable marriage, a motion picture actress must find a very weak or a very eminent husband. The trouble with. Marilyn is that she found a husband who used to be eminent. This is the one type of man she never should have married. Intellectually, however, she is incapable of judging character.”

Said Natasha Lytess, “The marriage was a big mistake from the very beginning. Marilyn has known this for a long time. People just don’t have one argument and decide on a divorce. There have been many quarrels, many quarrels.

“Why? Some people resent success in others. Mr. Di Maggio never could or never would consider Marilyn’s feelings and sensitivities.”

How about Joe’s sensitivities? How long could a man brought up in a religious home watch his wife’s sex appeal exploited?

You say Joe knew all about Marilyn’s calendar pictures when he married her? You say he knew what to expect from an actress whose major forte is her figure? He should have known. But he didn’t.

Joe thought that having reached the top, Marilyn would be content to taper off. He thought that perhaps he and his bride might work out the kind of relationship Laraine Day and Leo Durocher have, with Marilyn eventually doing only one picture a year. He practiced self-delusion, and that’s understandable because Joe was in love with Marilyn.

He thought, somehow, that with marriage, Marilyn would be given more conservative movie parts. When he visited her on the set of Show Business and saw how scanty her costume was for the “Heat Wave” number, he refused to pose. Nudity or near-nudity embarrasses him.

There are millions of kids throughout America who still idolize Di Maggio as an upright, clean-living athlete. Joe didn’t want them to see him posed beside a pinup—even if the pin-up was his own wife.

In telling the judge why she was requesting divorce, Marilyn said, “Your Honor, my husband would give in to moods where he wouldn’t speak to me for days. Five to even seven days. Sometimes as many as ten days. When I tried to appeal to him he’d say, ‘Stop nagging me!’ I was permitted to have no visitors at any time. I don’t believe I asked more than three times in nine months for a visitor. On one occasion when I was sick he did allow someone but it was under terrific strain. I volunteered to give up my work but it didn’t change his attitude at all. I hoped to have out of my marriage love, warmth, affection and understanding, but in our relationship there was only coldness and indifference.” Jerry Geisler asked, “What effect did this situation have on your health?” Marilyn answered, “I was under the care of a doctor.” She then stepped down from the witness stand and her testimony was corroborated by Inez Nelson, her business manager. A few minutes later the divorce was granted.

Right or wrong, Di Maggio is stuck with his basic nature. He cannot change.

To have saved her marriage, Marilyn would have had to give up The Seven Year Itch. She would have had to help Joe establish himself in a new career or some career allied to sports. She would have had to bolster his vanity. For a time she would have had to sacrifice her own career. She would have had to relinquish, at least temporarily, the limelight that placed her husband in the shadows.

She tried to do this with words. She told interviewers that Joe was the greatest, the most considerate, the most understanding and the more truly famous. She claimed that her marriage came first. But all the time she was working on her career, not on her marriage.

THE END

—BY WILLIAM BARBOUR

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE JANUARY 1955