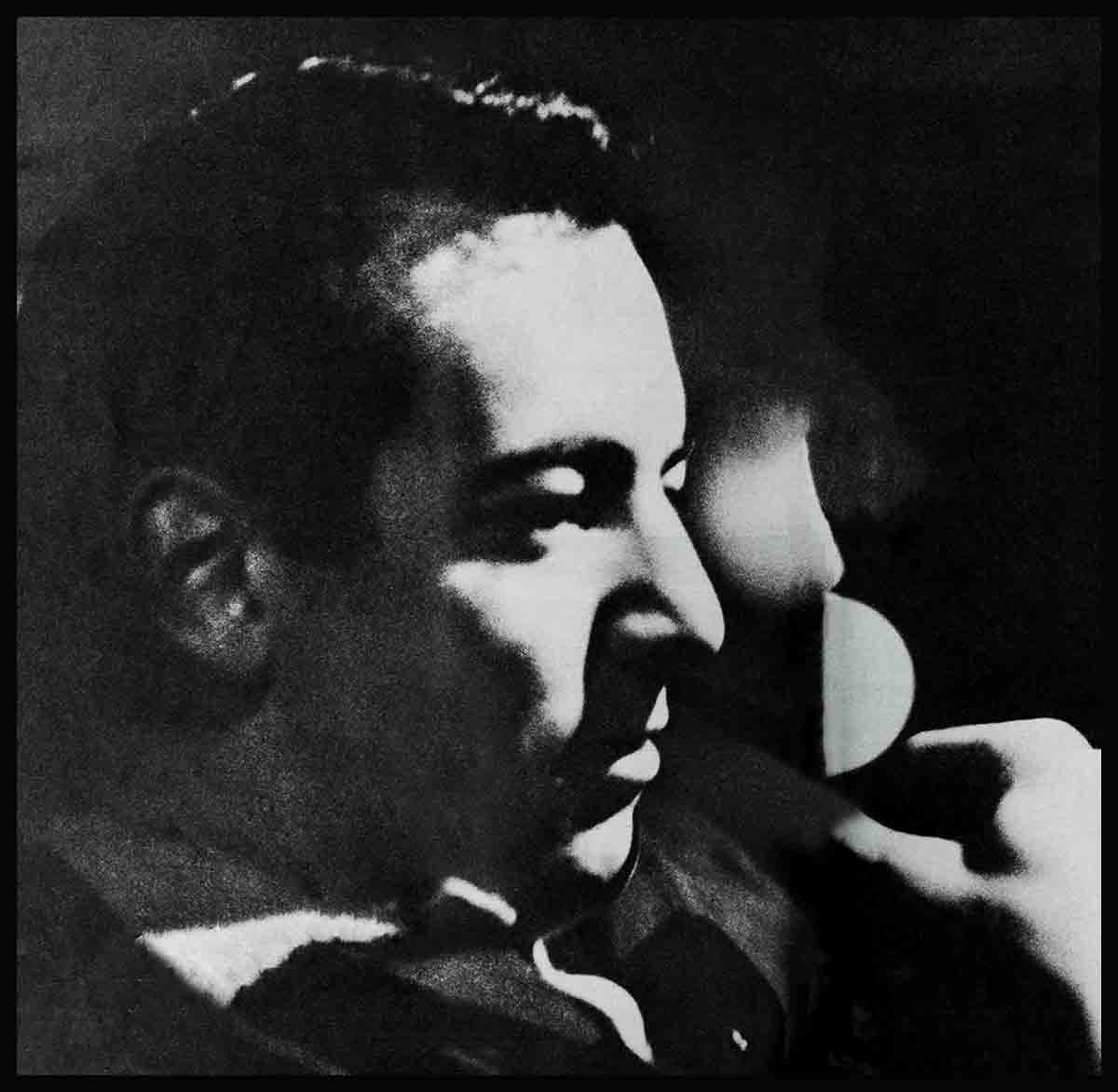

Wise Guy—Bobby Darin

“Hey, kid! Hide this!”’. . . From his tenement stoop in the Bronx, Bobby Cassatto stared at the knife that clattered on the steps by his feet. His black eyes seemed to grow as big and round as eight-balls. There was blood on the blade. Bobby didn’t want to have anything to do with it—nor with the hoodlum who commanded knew him—a bad egg in the neighborhood just out of a correction school. But he also knew the code of that neighborhood. So he picked up the weapon, took it inside and hid it under the stair well. Then he climbed the four flights up to his flat and slipped quietly into his room—with a sick foreboding of trouble.

Sure enough, his big sister, Nina, soon whistled him out of his room. Two plainclothes cops were standing beside his mother in the living room. “Okay, son,” one demanded, “let’s have the knife.”

“I got no knife.”

The man stepped threateningly toward him. Bobby’s mother held up her hand. “Don’t go near my son. I’ll handle this. Bobby . . . where is it?” she asked.

“It’s downstairs. I’ll get it.” He couldn’t lie to her. Anyway, they were bound to find it sooner or later.

Later, they found out he’d been framed in the stabbing and let him go. But each time a thing like that happened, a cloud he hated and feared seemed to settle lower over Bobby Cassatto’s head. Each time the ignorance, grinding poverty, tension and trouble of the slums he lived in grew and threatened to engulf him. Each time he told his mother, “I’ve got to get out of here, somehow, some way. I’ve got to get you out, too.” Sometimes, although young in years, he already sounded like a man.

And each time she nodded confidently. “You will.”

At that point, the odds seemed hopelessly long against him: he was sickly, homely, dirt poor and had no father. But Bobby Cassatto finally got out—way out. Today he’s Bobby Darin, the hottest new personality in show business.

Bobby has had six hit records in a row. Right now he’s booked tight in the nation’s top clubs until August. Recently, he signed a million-dollar contract with Paramount to act in pictures. And curiously, his biggest boost to all this was a song he recorded about a slasher from the same sort of slum jungle that Bobby fled. “Mack the Knife” was written before Bobby Darin was born, but no one has ever sung it quite like him.

When he belts out “Mack the Knife,” or anything else, and wherever he goes, Bobby goes all out. As a result, some people tab Bobby a cocky, egotistical wise guy. “He comes on too strong,” they criticize. “He’s always too eager, too brash, too much drive.”

Recently a Hollywood columnist took him apart. “Bobby Darin looked at his clippings,” he axed, “and said, ‘If I’m this good now what will I be when I’m Sinatra’s age?’ ”

Bobby didn’t say that. What he said, anxiously, was, “The way they write about me now scares me. How can I keep it up like Sinatra does? What will they be writing about me when I’m his age?”

That’s a very different thing, and back of it lies the specter that still haunts Bobby—the specter of poverty in the slums. He escapes it only by driving himself desperately. He’s still riding on that drive. He doesn’t dare let up. Because what he pulled out of is too close behind him.

Today, Bobby owns an array of suits, shoes, socks, shirts and ties. His laundry bill averages $50 a week. But there was a time when he had just one pair of frayed pants to his name and couldn’t afford to keep them cleaned. Only too recently he could claim nothing more valuable than the clothes on his back, a toothbrush, a razor and the little wooden cross he got as an altar boy.

Tragedy struck Bobby Darin and his mother, Polly, even before he was born, twenty-four years ago this May 14, in New York’s drab Harlem district. Right after conceiving his son, Bobby’s dad, Sam Cassatto, died of pneumonia—and Sam had been everything to Polly. For him she had renounced a comfortable world of wealth and social position. Polly never regretted her choice, but the struggle was hard. As Sam scratched out a bare living as cobbler and cabinet maker, Polly bore him four children. The eldest, Nina, was almost grown when Bobby arrived. Three others in between had died.

Depleted, sick and late in life for child bearing, Polly Cassatto rallied her frail strength after the shock of Sam’s death to survive a precarious pregnancy and birth. “Because,” Bobby believes, “to her, Dad was coming back through me. She was a one-man woman—and I became that one man. She lived to make something good out of me. And I knew I had to succeed if just for her sake alone.” From the start, it was Bobby and his mom, together against the world, a hostile world.

An undertaking shark had gobbled all Sam’s meager insurance in a needlessly expensive funeral. For a while, Polly tried to work, but anemia, varicose veins and arthritis kept her too often in bed. Finally, she went on Home Relief to survive. Nina quit school and took a job. The Cassattos moved to a dark “railroad flat” in the teeming Bronx almost under the shadow of the Triborough Bridge. And, for a long time, little Bobby lived under a more sombre shadow—death.

Right after he was born, he shriveled up like a raisin. “Probably,” Bobby Darin cracks, “from the fresh air.” Bobby’s handy with quips, like that, but most have a bite. At any rate, he was so weak that all he could keep down was goat’s milk imported from Belgium, which Polly sometimes skipped her own meals to buy. Still, when she wheeled him out on the sidewalk for some sun, people would peer down at the wizened face—all burning black eyes, it seemed, in a patch of blue skin—and shake their heads.

“That kid’s gonna die,” they told Polly rudely. “What you knockin’ yourself out for?”

“He won’t die,” she came back fiercely. “I won’t let him.” And, of course, she didn’t, although always he was sickly. Later, he suffered four straight attacks of rheumatic fever and acquired a double heart murmur which rates Bobby Darin 4-F for the Service today.

Back then, in her struggle, Bobby’s mother had no place to turn for help. She neither asked, received, nor expected any lift from her own family. To them it was bad enough that she had run away from home to sing and dance. But to marry an Italian immigrant’s son was the end. Polly was promptly disowned and cut off cold. But she never forgot that she was Pauline Walden. She named her son Walden Robert Cassatto. And, when he grew up enough, she told him who he was.

“You bear a proud name and an old one,” she’d say to the puzzled boy. “The Waldens have been in America for 350 years. They helped settle Massachusetts and New England. Thoreau’s pond was named after them. They’re related to the first families who came over on the Mayflower.”

“What good’s all that junk?” Bobby fired back. “What does it mean to us, to me—here?”

“You’ll understand when you grow up,” she’d tell him. “And you won’t always stay here.” They both knew he had to get out.

Even today, Bobby Darin’s not sure he understands what, if anything, it means to be a Walden. He’s yet to meet a relative on his mother’s side, and doesn’t care if he ever does. But he always felt that somehow he was different, as was his mother, from the polyglot thousands who swarmed around him. Someday he’d get out, just like she said. She believed so strongly in him, he knew he just couldn’t let her down.

Sam Cassatto’s relatives had spurned them too, when Sam died. They’d always disliked Polly. She was fair, she was “foreign,” a mistake Sam had made. Once widowed, they let her and her kids alone.

So, Bobby Cassatto grew up sensing, acutely, that he was out of place and wondering desperately what his place was.

Polly couldn’t tell him that. All she could do was set an example of gentleness, courage and pride to help him face and defeat the rude world of the Bronx tenements.

Bobby’s playground was the asphalt jungle. He dodged trucks playing stickball, cooled off in sweltering summers at the spraying “johnnypump” hydrants until cops scattered the ragged bathers. He romped with all colors and creeds, saw some steal, others mutilate their enemies and run in outlaw packs.

Although Polly’s railroad flat on 135th Street was as poor as the next one, it was neat as a pin. The Cassattos lived on Relief throughout Bobby’s boyhood, helped out when Nina and her new husband, Charlie Maffia, moved in. Still, there were always books that somehow Polly had collected. Sick or not, Polly sang around the house, and made a happy home. Toys miraculously showed up at Christmas and once even a battered bike. The scratchy radio was always tuned in to good music and good dramas. Sundays, Bobby served the altar at the Episcopal church. “I guess you’d say I had nothing but insecurity,” muses Bobby. “But I never felt that way. At home, I had the security of thoughts and knowledge. And, above all, love, warmth and gentleness.”

He watched kids around him get swatted by their parents, screamed at and cursed. Yet, he doesn’t remember his mother lifting a hand against him all his boyhood, or even raising her voice, and she had plenty of provocations.

Once, when he was only six, and his mother was sick in bed, Bobby ventured out on the fire escape and dangled perilously from his knees four stories above the pavement. His mother saw it all, but, even though her heart seemed to stop, she kept quiet until he crawled back in and she could explain why he must never do that again. Another time, she caught Bobby in the kitchen industriously rolling eggs off the table to splatter on the floor—“bombing Japs.” Eggs were a Relief surplus then, and Bobby had destroyed nine dozen—family breakfasts for a month—before she stopped him. But his mom quietly cleaned up the mess, and her silence was more punishing than a licking.

Because his skinny body seemed to harbor every germ that invaded the Bronx, Bobby was kept out of school until he was almost eight. But he was buried in a book from the time he was four. The day Polly finally took him to PS. 43, the teacher frowned.

“You’re too old for kindergarten,” she pondered. “But you obviously can’t do first grade work. These children are already beginning to read.”

“Try him,” suggested Polly.

Bobby spied a familiar volume on the teacher’s desk, which she had been scanning for her own pleasure. He’d been reading that book since he was five. He flipped it to “Julius Caesar” and rattled through Shakespeare’s play as if it were “Mother Goose.”

“You’re a very unusual boy,” gasped the teacher. She placed him in 1-A. He skipped half-grades five times. When he moved on to junior high, Bobby Cassatto was valedictorian of his class.

“It wasn’t such a feat,” debunks Bobby today. “I had no competition.”

Of course, that wasn’t entirely true. Dog fight competition was the law of life in the Bronx. And a kid like Bobby Cassatto was strictly a short-ender in the things that seemed to count. He was no hero because he was smart in school. The kids derisively called him “Dictionary,” “Wise Guy,” “Genius” and, of course, “Teacher’s Pet.” They roughed up his puny frame at school and chased him home afterward. He worshipped big league baseball, but at sports he was nothing. When he looked in the mirror, Bobby saw only a bony nose, pinched, drawn cheeks and black eyes like coal-holes. He told himself he was ugly. Sometimes, he didn’t have to tell himself.

There had always been girls on Bobby Cassatto’s mind—on his mind and rubbing his sensitive emotions raw. There was Eleanor in PS. 43, a pretty blonde, but she wouldn’t even talk to him. There was Gloria right on the block, a hopeless crush who never knew he existed or cared. And Mary, whom he tried to impress by eating grass and match books. She only said, “Bet you can’t eat tar.” So he got a hunk out of a street repair pot, swallowed it and was deathly sick while she giggled.

All these rebuffs, torments and persecutions Bobby confided to his mother. “I was no mama’s boy,” he hastens to explain. “No silver cord or anything like that. We were just very close. She was both a father and a mother.”

At such times, Polly “Never mind. When you grow up you’ll have it all over these kids. They won’t know what to do with their lives and you will.” He believed her, but adulthood seemed a long way off to a boy just entering adolescence. Bobby wanted to be popular now, wanted to belong.

“I knew I didn’t belong where I lived and that I never would,” he recalls. “But when you’re breaking into your teens you sure don’t want to be an isolationist!” At PS. 37, in junior high, he began looking around for a weapon. Pretty soon he found one: He could make people laugh.

“I studied the kids,” he says, “and I realized that if I made them laugh I could control them. So I deliberately turned myself into a clown.” He practiced gags, jokes, and wisecracks. He twisted his plain face into comical shapes, hammed up and mimicked everything. It got results: The tough guys liked to have a jester. Even the girls said, “You aren’t the best looking, but you’re the most fun.”

That was the beginning of Bobby Darin, entertainer. Clowning around desperately, he first glimpsed a slit of light in an escape hatch from the Bronx slums. “I noticed a change in myself about then,” Bobby reports. “I began to drive. I figured show business of some sort was my best and fastest hitch out.”

So, when he splintered his leg in a street accident, some months later, Bobby spent his time in bed mastering a ukulele. He borrowed a flute from school and a horn and figured them out, scrounged the neighborhood for records and listened to them time and time again on his ancient Victrola. When he had the money, he haunted movies, watching the pros.

In P.S. 37 he talked to his guidance teacher. Bobby wanted to switch to a performance school, and he explained why. The counselor nodded understandingly. “But,” he argued wisely, “you’re bright. Get a good academic foundation first. Then, whatever you do, you’ll be better at it.” At home, Polly Cassatto agreed. So, when he was twelve, Bobby took the stiff entrance exam for the Bronx High School of Science. Bronx Science is one of the toughest high schools in the United States. It exists for gifted students only. Bobby passed the test. He got a “needy” scholarship to help and graduated at sixteen.

“Those four years,” Bobby says today, “were my first breakaway, the first time I got a look outside my neighborhood. I met an entirely different kind of crowd. For the first time, I discovered real competition in school. It was an eye-opener and a challenge.”

Bobby was in the odd spot of being seduced by learning. Chemistry, physics, advanced math—which he necessarily bored into—tugged at him like sirens. As Bobby puts it, “Learning both fascinated and frightened me. I was afraid I’d get to like that stuff too much. It wasn’t the side I wanted nurtured. The thought of being an entertainer had gotten deep into my blood. And yet—”

He’d had his first taste of conflict.

Nowadays, Bobby Darin can read and study as a relaxed hobby. Back then it churned him up inside. And there was something else: He was still clowning to win attention, and he was sick of the role.

One week he heard about a five-piece dance band some school guys were working up. All spots were filled except the drums. “I’m a drummer,” lied Bobby to the leader.

“Okay, show up Tuesday and we’ll try you out.”

Tuesday was a week off. He had a friend named Joe who owned a whole set of drums. So Bobby raced up to Joe’s place on 141st Street and borrowed them. All he asked was, “How do you hold the sticks, Joe?”

That night he set them up in his living room and practiced hard. When neighbors pounded on the walls, he took them down to the basement. Six days later he tried out and got the job. For Bobby, it opened up an exciting new world.

“Suddenly, I meant something at school,” says Bobby. “I wasn’t just a kookie little clown. I was Bobby Cassatto, the hot drummer. You know,” Bobby confesses, “most people want to be liked for what they are. With me it’s always been the reverse. I want to be liked for what I do.”

The last summer in high school, Bobby and the group got a job at a hotel in the Catskills. They waited on tables by day, played dances and put on shows at night. In the fall, Bobby entered Hunter College. First thing he did was join the Drama Society; Hunter College in the Bronx is no drama school. Bobby had chosen it because it was close by and free.

“The first year was great,” says Bobby. “I did skits in variety shows. But the next year the Society put me to work on sets. They let me read for things but never do them. I lost interest in school. I had to get going.”

Two weeks after Bobby quit school he spotted an ad in a show business sheet: “Wanted: Actors to try out for the Children’s Theater Group.” Bobby hustled down to an office off Broadway, came out with a job. For the next seven weeks he performed in elementary school auditoriums around the East Coast. He played a wicked Indian chief and kids kicked him in the shins as he came out of school buildings. But he drew $45 a week; he was an actor, he kidded himself. But he couldn’t kid himself long.

Back in New York, when Bobby Cassatto padded around theatrical agencies, all he could offer for experience was the Indian. They laughed at him. Hungry, he took a job as an office boy, hoping to exist until summer when he could go up again to the Catskills. And all the while, at the back of his mind, was the image of his mother in their Bronx slum—an image which kept him going.

That summer proved the turning-point of his career. In the Catskills, he met Don Kirschner, an ambitious young college boy who also wrote songs. Don became very fond of Bobby’s work and that fall, introduced him to an agent. The agent liked Bobby’s voice better than his songs and at first Bobby began to record only other people’s music.

He made more than fifteen losers and sang in dozens of small night clubs up and down the country before he finally had his hit. And he had to write that one himself. It was “Splish-Splash.”

This sent him winging. He cleared $25,000 from that and the first thing Bobby did was to buy a house for his mother in Lake Hiawatha, New Jersey, out in the fresh air, away from the Bronx. And it was a big, big day for him when he moved all his family—Nina, Charlie and his nieces there.

One night, last year, he was watching his good friend Jerry Lewis, at a club in Hollywood, when a call from New Jersey came for him backstage. No one there knew where he was, so he didn’t find out about it until late that night. He called home with an unexplained chill around his heart.

“Bobby, Mommy’s in the hospital,” said Nina. “She’s had a bad stroke. Maybe you’d better come.”

He couldn’t get a plane until morning. When he arrived it was too late. They all said that right before Polly Cassatto died she kept repeating her son’s name.

At the funeral Bobby Darin stood a long time before the flower banked bier. He couldn’t believe she was gone. He thought of the things he should have done, and hadn’t, he consoled himself that before she died. his mother knew of some that he had. The things yet undone, he’d better get about doing.

He went home and into his room alone. Very softly, he began to cry. His mother had meant so much to him. If it weren’t for her encouragement, he never would have stuck it out this long. They were so close. Then he stopped crying, dried his eyes, lifted the phone receiver and put in a call to Hollywood.

“Steve? Bobby. Where do I meet you?”

“Are you sure you’re ready?”

“Yes,” said Bobby. That night he took a plane out and the next night he was singing again with everything he had.

“I knew that’s the way she would have wanted it,” says Bobby.

—KIRTLEY BASKETTE

HEAR BOBBY SING ON THE ATCO LABEL AND THE TITLE SONG IN WARNERS’ “TALL STORY.”

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE APRIL 1960