The Case Of The Vanquished Bachelor—James Stewart

During football season last fall a group of Beverly Hills buddies were having Saturday night dinner together. Jimmy and Gloria Stewart were among the guests, so inevitably the conversation turned to Princeton’s grid victory of that afternoon.

“I get excited enough about the games now,” Jimmy declared, “but when my two boys are in college, I guess I’ll have to figure a way to work in the East during the fall.”

Someone said with a straight face, “I thought your two youngsters were girls.”

Falling for the rib, Jimmy explained, “The two youngest are girls, but my two oldest are both boys.” Then, gradually, a grin began to spread. “Our two oldest,” he amended, and across the table he met Gloria’s warm smile.

No more eloquent incident could be cited to indicate the close-knit happiness of the clan Stewart, because the two boys mentioned are Ronald and Michael, sons of Gloria Hatrick MacLean Stewart by her first marriage.

Wisenheimers in Hollywood still can’t quite believe in Stewart, the Benedict Arnold—even after five years—bearing in mind as they do that until Jimmy was forty-two, he was the archetype slippery slim, the bachelor incarnate.

Five years later, the perennial bachelor might well be described as Squire Stewart. Marriage becomes him like his favorite tweeds, and he finds fatherhood a comfortable and preoccupying condition. His ties to his children are always with him.

A good example of this is when during the summer of 1954, Jimmy—with Gloria—made his first trip to the continent. As Colonel in command of an Air Force bomber squadron, he had flown over it hundreds of times during the war, but this was his first foot contact with the streets of Paris, Rome, and twelve other major European cities.

In Rome, where “Harvey” was playing, Jimmy was presented with a huge white rabbit, alive! Naturally pictures were taken, and these made their way in due time to Beverly Hills where they were spotted by an entranced Judy and Kelly.

“We’ll be so happy to have you home again, and we hope the big white rabbit you are bringing us will be happy here, too,” wrote the twins, courtesy of their nurse who “knows how to spell.”

When this communique reached the Stewarts, they had gone on to Munich, having left the rabbit in the arms of a delighted Roman child. “We’ll have to make arrangements to pick up a rabbit on our way home,” Jimmy said chagrined, “But it would have been impossible to tote that animal all over Europe.”

“Even worse than toting that rugby football,” agreed Gloria with a broad smile. Just a week before, Jimmy had been given a football, autographed by all members of the team, at a rugby match in Rome. “The boys will be crazy about this,” he had observed, and he made arrangements to have it wrapped and tied with a system of cords and handle so he could carry it. Carry it he did—over the continent of Europe, and across the width of the United States! And the minute he got off the plane he headed for the pet shop for the girls’ rabbit.

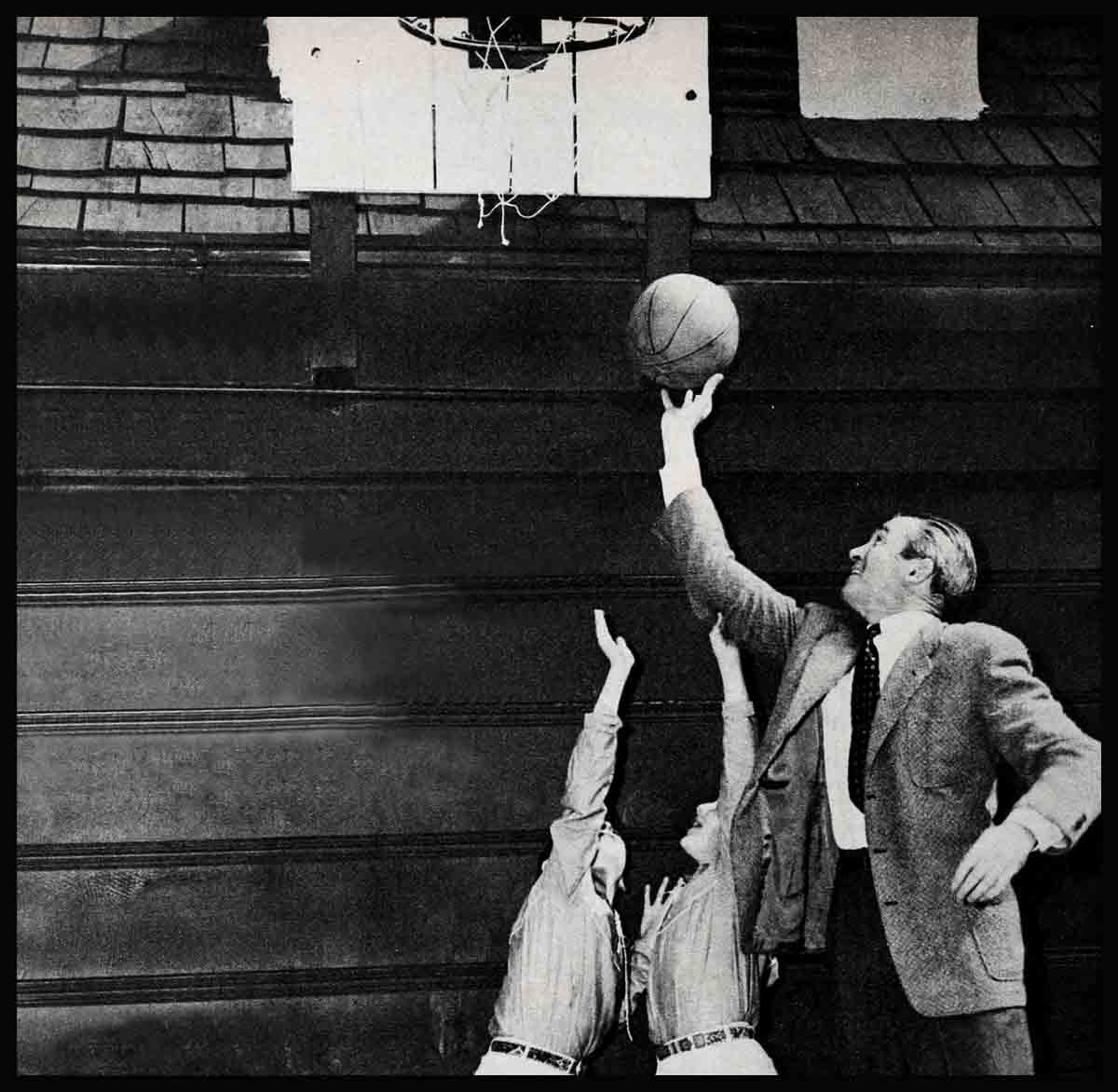

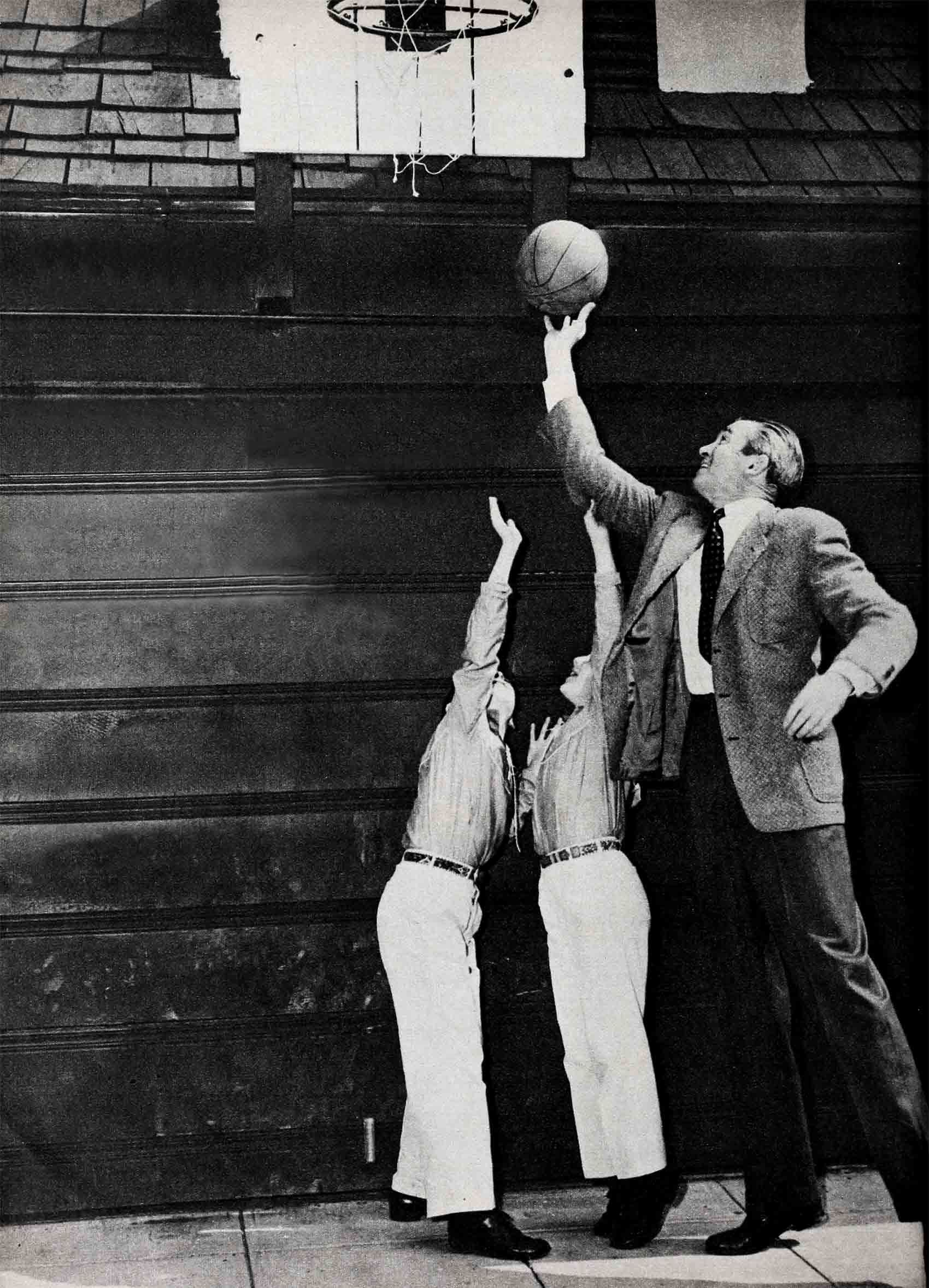

Although only two of Jimmy’s most recent pictures (“The Glenn Miller Story,” “Rear Window,” “Strategic Air Command,” “The Far Country,” and “The Man from Laramie”) have been Westerns, the boys regard their Top Hand as strictly from Stetson. They bedeviled him until he agreed to build them a fort to hold off the Beverly Hills tribe of marauding Indians. Actually this edifice is a stockade (it lacks a roof), but it has thirty-six square feet of grassy floorspace, and its chinked log walls are equipped with embrasures from which to fire Colt .45’s or Winchester .73’s.

Although the boys were dubious at first about permitting the twins to help repulse the war parties, Jimmy made a settlement ruling that all hands must share in defense. “After all,” he reminded them, “there are very few boys lucky enough to have two little sisters to help.”

As the family consisted Before Twins, of Jimmy, Gloria, Ronald and Michael, the Stewarts felt that they must move to larger quarters if they were to be six. They were shown hilltop moderns full of glass expanses for children to break, and they were shown valley provincials full of quaint stairways where children could break their arms; eventually they inspected a square-rigged, placid and substantial house in Beverly Hills. Its windows were ample, but they did not extend to the floor; its stairways were shallow and wide. Its facade was overgrown with ivy.

“It looks like a dormitory,” said Gloria.

“Well?” said Jimmy.

Two of this dormitory’s occupants were overheard taking an extensive interest in their forthcoming bunk mate before the stork had let his multiple intentions be known.

“It’s going to be mine, no matter what it is.” insisted Michael.

“That baby is going to be mine,” countered Ronald.

“The two of you are going to have to learn to share,” ruled their mother. “The baby will belong to each of you equally, both of you together.” She gave them a brief lecture on the beauties of cooperation and generosity, but their attention was spotty and restless.

“After all, you feel that Belo belongs to both of you,” she wound up. Belo is the family’s huge German Shepherd dog, now ten years old and blind, hence doubly deserving of a small boy’s special love. Besides, he is older than either boy, thus commands respect.

“Nope,” said Ronald, “Belo belongs to you. You had him in the family before you had us. This baby is different. I’m the oldest so it should belong to me. If there’s another one, Michael can have it when the time comes.”

And so it stood until Gloria learned that she was to have twins “right out of left field, since there is no record of twins in either of our families.” The boys were impressed. Michael said softly, “Gosh, that’s swell of you, Mother. Now each one of us can have a baby all to himself.”

Ronald still discerned a problem. “Yeah, it’s okay for us, but what about Belo? What about a baby for Belo?”

“A problem Belo will have to solve for himself,” observed Gloria dryly.

The fact of Jimmy’s double-feature fatherhood has been fraught with pride for papa from the day X-rays promised twin Stewarts. Promptly, Jimmy took Gloria shopping for nursery furniture.

“We’ll take two of these beds,” Jimmy said.

The sales woman was eager to be helpful. “One pink and one, perhaps, blue?”

“No. Just alike. Two junior chests of drawers. Two high chairs. Two of everything.”

Impressed by the legends of Hollywood elegance, the saleswoman exclaimed, “How nice to plan two nurseries, one on the second floor and one, perhaps, on the first. Wherever the family is, the baby can be, too.”

Responded Jimmy without change of expression, “Not two nurseries. Two babies, twins.”

The twins were born, by Caesarian section, on May 7, 1951. If the birth had been ordinary, Kelly would have been the older twin, but Judy has always been larger, so she arrived first. The girls are fraternal, not identical twins. In appearance they are as different as sisters can be.

Judy has thick straight, flaxen hair which is worn in a Dutch bob. Her eyes are almost elliptical, giving her a wise, contemplative look; and they’re blue as the deep sea. She has a good deal of natural dignity and rarely rushes into new friendships. Some people think she looks and acts like Jimmy. Michael is positive that she looks and acts like him. “After all, she’s my sister.”

Kelly has a cherub’s mass of curly chestnut hair. Her eyes are hazel, her nose is tiptilted and she is filled with puppylike curiosity and gregariousness. More fragile than Judy, she takes her childhood ailments very seriously. She runs higher fevers than Judy, her colds last longer, her immunization shots produce stronger reaction. When Kelly is ill, Judy mothers her, brings her drinks of water (spilled only here and there), plays contentedly in the nursery as if there were no beckoning garden just beyond the windows, and in general tries to be of comfort.

Judy’s serious-mindedness shows in other ways. She will sit for hours holding a book on her lap and turning the pages one by one studying pictures and puzzling over the alluring, mysterious lines of type. She never flips ten or fifteen pages at a time, child-fashion, but treats books with adult respect.

Yet it is Judy who has the temper. One afternoon she was playing with her mother’s cinch belt which has a dual metal post closure, the left half sliding from the top of the right into a slot. In order to close the belt, a pair of small hands must first understand the principle and then hold steady enough to bring the solid cylinder and the hollow cylinder into juxtaposition and slide them together. Actually it is a problem to baffle a six-year-old, but Judy took it on.

She worked for long moments, her tongue extended sidewards between her teeth, her forehead wrinkled in consternation. When she found she couldn’t close the belt, she hurled it to the floor, clenched her fists and held them beside her head, as if in anger at the inadequacy of her own brain, meanwhile uttering brief squeals of infuriated frustration.

Then she tried again. Finally the nurse, Mrs. Wilson (who has been with the youngsters since birth) showed her how to steady an elbow against her side, bring the posts into alignment and slide them together. Judy’s sigh of satisfaction could have been heard into Kansas.

Kelly is not so intense. She will work at placing those educational-toy colored posts into their slots, but if one proves to be stubborn she casts it aside with a shrug and goes on to something else. When Judy is going through one of her determined attempts-to lick a problem, Kelly is inclined to pat her sister’s head sympathetically. Eventually, Kelly may ask, “Why bother? I don’t think it’s worth it, do you?” So far, Judy cannot agree.

Kelly’s great enthusiasm is clothes. It is she who decides (if allowed by her mother or Mrs. Wilson) which outfit she and Judy will wear. Judy never questions the choice.

Right now, Kelly—like most small girls—likes any color at all as long as it is red. Her favorite costume is a pair of red corduroy jumper trousers combined with a yellow pullover and cardigan sweater set.

From the Canadian location for “The Far Country,” Jimmy sent the girls each a Scotch tartan beret topped by a red pompon. Unfortunately the berets were a size too small. That didn’t bother Kelly. She was so enthralled by her new headgear that she perched it on top of her curls and walked around stiff-necked. A moment later she relaxed and the beret fell off. Chuckling, she picked up the topper and replaced it, pancake fashion, above her curls.

Judy tried on her beret before a mirror, discovered that it didn’t fit, shook her head, and tossed the bonnet aside.

On another occasion, Jimmy bought blue jeans “just like Papa’s” for his twins. For weeks Kelly would wear nothing else, and even clothes-unconscious Judy was inclined to examine her mirrored image with an expression bordering upon genuine approval.

Judy was the first of the twins to talk and her initial word was “Papa!” used imperatively because she wanted to call his attention to minor mayhem being committed by Kelly. Miss Kelly, the mischievous sister, was biting dignified Judy’s arm. Judy, instead of retaliating in kind (she has the same number of teeth), called on higher authority.

Papa acted. He paddled Miss Kelly on a well-padded area; no real damage was done to anything except Kelly’s ego, but she carried on as if Belo had died. She’s the dramatic one.

Kelly is the more garrulous sister, too. When Jimmy brought home a pair of Indian dolls, it was Kelly who gasped, “Oh, brother!” When Judy, driving her tricycle with magnificent verve, bangs it into the fence or a tree, it is Kelly who shouts, “Oh, brother!”

Incidentally, the two Stewart tricycles are the only objects the girls have ever owned which do not match exactly. One has a blue frame and the other red. Gloria and Jimmy decided to award the tricycles as a unit, without designating which vehicle belonged to which sister. The girls seemed to accept them in the same manner. Neither child has laid positive claim to one or the other. Sometimes Judy will ride the red, sometimes the blue. By some sort of tacit arrangement however, Judy is the one who decides who is to ride what.

Kelly it is who carries on long conversations with the servants. She’s a round-eyed admirer of Panlichet, the French butler, and she has learned a surprising amount of French from being with him. One day she marched into the dining room where Panlichet was polishing silver, climbed onto a chair, composed herself, and delivered her first complete sentence: “Panlichet, I want to talk to you.” She also tells him “Bon jour” in the morning, “Bon soir,” at night, and “Au revoir” when she leaves the house during the day.

Judy is inclined to observe her sister’s linguistics with an indulgently humorous expression which is a miniature of the wryly amused Stewart look so familiar to motion-picture and TV fans.

Judy seldom attempts to copy her sister, but Kelly is inclined to mimic anything that blond Judy does. Curlytop Kelly seems to be somewhat envious of Judy’s flaxen Dutch bob and on two occasions has eluded the nurse and her mother long enough to lay hand on a pair of manicure scissors and a comb, attempting to cut bangs as she has seen the barber do for Judy.

The result is, of course, a ruffle of tiny rebellious curls instead of the sedate coiffure into which Judy’s hair likes to fall.

The general give and take of the twins relationship stops short in one area: each knows her own particular nicknames and refuses to be called by any other.

The Stewart family is quick to apply sportive labels to its loved ones, so shortly after birth Judy became “Tweedledum” and Kelly became “Tweedledee.” There were other aliases: Judy became “Foxy Blue Eyes” and Kelly became “Irish.” Judy became “Pretzel Puss” and Kelly became “Needle Nose.”

While Jimmy was tucking the girls into bed one night he said to Judy, “Okay, Needle Nose, you’ve horsed around long enough. Into the hay you go this minute.”

Judy’s eyes flew wide with indignation. “Me not Needle Nose,” she corrected. “Kelly, Needle Nose. Me, Pretzel Puss. Say it, Papa.”

Mr. Stewart bowed. “I beg your pardon,” he said. “I’m sorry to have made such an obvious mistake. Please get into bed now, Pretzel Puss. And goodnight to you, Needle Nose.”

Two little girls pulled the covers up around their necks and two little girls were lost in giggles.

Jimmy turned out the light and considered the situation as he descended the stairs. Were the girls pulling a fast one on him? Was Judy really? . . . Or was it Kelly? . . .

“I’ll never know,” he decided.

THE END

—BY FREDDA DUDLEY

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE FEBRUARY 1955

gralion torile

11 Ağustos 2023Perfect piece of work you have done, this website is really cool with good info