1955 Sexation: Sheree North

There are two Sheree Norths. Two, we said. Count them.

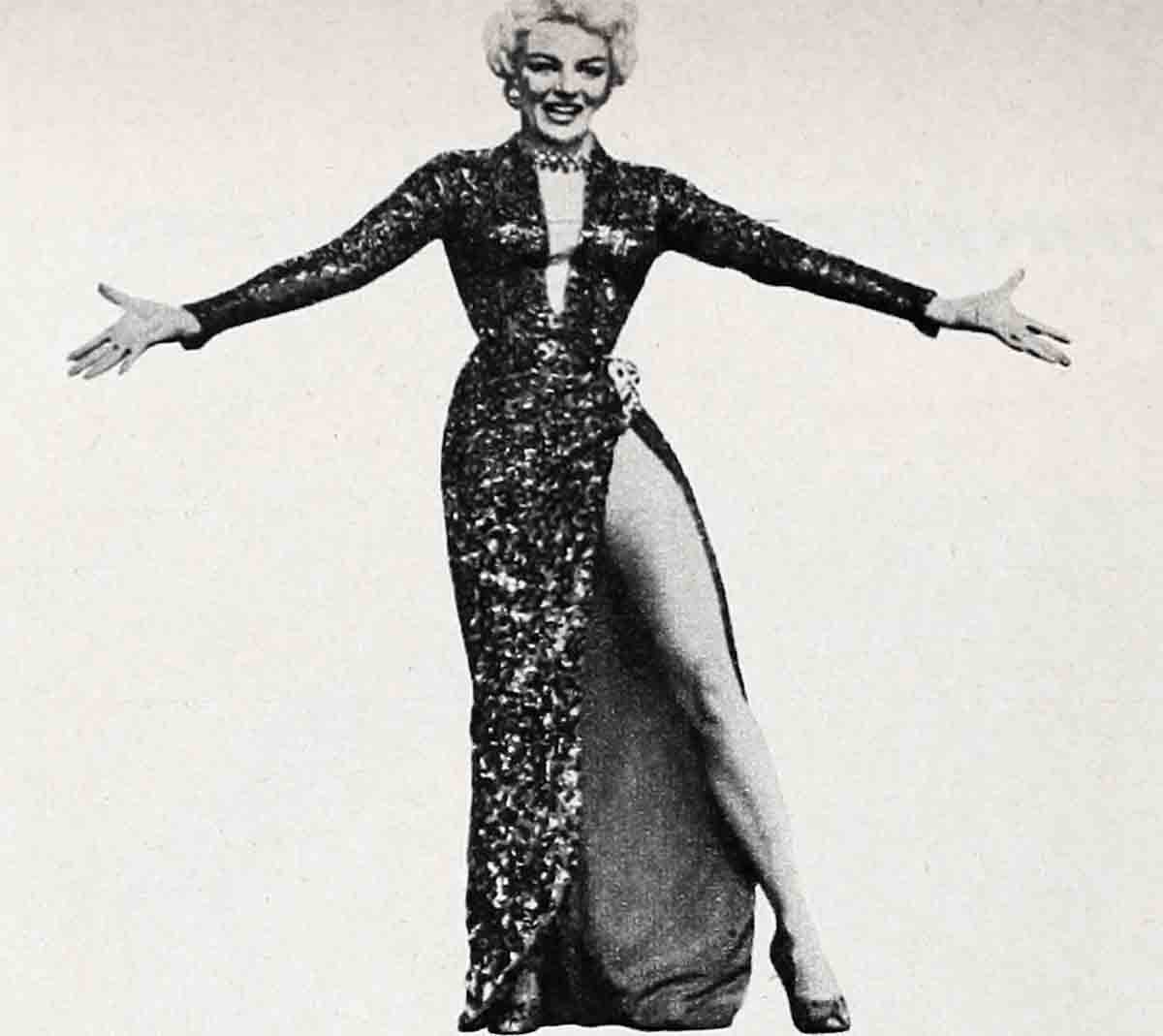

One is a sultry, sexy, whipped-cream blond, with an opulently curved figure and spectacular legs, whose uninhibited style of dancing in the picture “How to Be Very, Very Popular,” co-starring Betty Grable, has the Hollywood movie censors mumbling in their beards.

The other is a demure, quiet-eyed woman who attends PTA meetings, goes to church on Sundays and recently rented a house in a secluded canyon some distance from the bustle of Hollywood be- cause it is near a school and playground and is in a good neighborhood “to bring up my six-year-old daughter, Dawn.

“I know what it’s like to be poor and live on the wrong side of town,” says she. “And now that I’m getting some breaks, I want to give Dawn all the things I didn’t have when I was her age.”

One Sheree talks bop. This reflects her show-business background, her more than ten years as chorus girl, model and hoofer. This lushly contoured lovely—who stepped into the starring role in “How to Be Very, Very Popular” when Marilyn Monroe stepped out—is fully aware of her unusual terpsichorean agility. But she doesn’t think her dancing needs censorship. “It’s just real frantic,” she explains.

The dance number that caused all the comment is called “Shake, Rattle and Roll.” Describing it, Sheree said, “It’s the wildest—the coolest—the craziest yet.”

But she can’t understand what caused the censor’s eyebrows to flap up. “It positively has no bumps or grinds,” says she. “It’s just a real nervous number.”

The other Sheree reads Thomas Wolfe, studies art appreciation and attends spare-time classes in drama and speech. This girl wears Scotch tweeds and conservative British hats imported from London’s Old Bond Street. And her evening hours are spent with Dawn, helping her master the intricacies of reading, spelling and arithmetic. And jump rope, too.

Sheree understood her daughter’s need for acceptance by her schoolmates. This was one thing she had lacked and most wanted when she was Dawn’s age—which was not too long ago. Married at fifteen and separated from her husband a year later, soon after the baby was born, Sheree had grown up in a heartbreak world where each day was a bitter struggle for survival. And now, at 22, with success sitting lightly on her pink-and-tan shoulders, she could relax a little and try to share with Dawn this new-found feeling of security.

Success has been a recent arrival for Sheree. And it took its own sweet time getting here. For Sheree has been dancing—for self satisfaction, for personal recognition and for money—practically all her life. Her feet had a dancing urge when she was only three years old. At six, she gave her first performance—un-announced—on a public stage. At 11½, she was a professional hoofer. When she was sixteen she supported her daughter by kicking up her heels in the chorus line at Hollywood’s Florentine Garden. And at nineteen she was fed up with it all.

And then, at that low ebb in her life, it happened. Just like in the movies. Fate, or whoever taps you on the shoulder with that magic wand, stepped in and made a fast parlay for Sheree. She danced from the Broadway stage to a movie at Paramount to a TV show with Bing Crosby. She scored a sensation every time. And after that she was really in.

Twentieth Century-Fox tested her and signed her. They handed her the role and a seven-year contract at a four-figure weekly salary. But this was not to be squandered, like some movie stars, on swimming pools and fancy convertibles. Not Sheree.

“I’m putting all my spare cash into annuities,” says she. “That way I can really be sure that Dawn will have some security when she grows up.”

When Sheree speaks of security her hazel eyes are deeply serious, for she lived without it for a long, long time.

“I was born right in the heart of Hollywood,” she says, “but I don’t remember the house because our family moved soon after that. I don’t remember my father either. I never knew him. He left my mother before I was born, and she never talked about him.

“I grew up in a very poor neighborhood. Most all of the families around us lived on relief and we did, too, some of the time. I remember standing in line to get groceries and coupons which we used to have our shoes repaired. Sometimes my Grandma baked apple pies and gave them to the relief workers and they repaid her with extra groceries. That was lucky for us because we had a lot of mouths to feed at our house: my Grandma Shoard, who had a Scotch accent as thick as oatmeal; my half brother Don, six years older than I; and my half sister, Janet, four years older. And, of course, my mother, June Bethel. My real name is Dawn Bethel.

“Mother was a practical nurse, and the money she earned at this just about paid the rent. She also did pearl stringing and jewelry designing, which she had learned as a girl in Chicago. We were a healthy, fighting family, but we were not very close. We all had our problems trying to survive and adjust to a world without money. My brother and sister were much more independent and outgoing than I. I was the shy one. And I guess I suffered because of it.

“School was a problem. I hated it. I didn’t have any pretty dresses to wear, only hand-me-downs. And I never did feel that I belonged. Some of the teachers were pretty cruel and rough. They smacked you with their rulers on the knuckles or on the fanny. One teacher was a terror. She had her special pets, and I wasn’t one of them.

“I don’t think I was a bad child. I just needed some love and understanding. But I didn’t get it. I just got sore knuckles from that darn ruler. Naturally I hated to go to class. I was miserable when I was there. And of course my studies suffered. Even when I thought I knew the answers I was afraid to raise my hand. Because I was afraid of what would happen if my answer was wrong.

“Mother could have helped, but she was seldom home. She was much too busy earning a living for all of us to have time for my childish problems. Grandma took care of us at home. She had a sympathetic ear for my troubles, but she didn’t really understand. She’d listen while I unloaded my miseries and then she’d say, ‘There, there, child. Come out in the kitchen with me and I’ll boil you an egg.’ Poor Grandma. Eggs were expensive luxuries in those days, and she thought a boiled egg should solve any problem.

“So I had to work out my troubles alone. And I had two methods: I cried and I lied. I soon learned that crying was no good in front of people. They pointed at you and hollered, ‘Crybaby!’ Or they looked at you in a way that was worse than name calling. So I’d go home after school and lock the bedroom door and lie on the bed and cry alone. And it always worked. After a while I’d feel much better. I’d wash my face and stand in front of the mirror and put some make-up on. I’d pretend that I was a beautiful movie star. Then I’d go out and find some of the kids and tell some lies.

“Maybe the psychologists would have a fancy name for this, but I just made up the craziest stories. I’d say, ‘I have a swimming pool right under my house.’ And for a short time I was a person of some importance. At least until the kids could check up on my wild tales with their parents. Then I’d think up some new stories.”

Sheree had started dancing at home. Partly because her feet wouldn’t keep still, and partly because she wanted praise and adult acceptance. In high heels and a borrowed gown, plumped out with wadded stockings stuffed into the bodies, she danced, sang and gave an impersonation of Mae West. She also told funny stories and took a few pratfalls when the occasion seemed to demand it. All this in front of the members of her immediate family plus an assortment of uncles, aunts and cousins who were living with them at the time.

“They were a tough audience,” she remembers. “I usually had to knock myself out to get some applause.”

She made her stage debut at the age of six. Well, it wasn’t exactly a debut, but she did get up on a public stage and dance Mother had taken the kids to a Christmas party and program at a nearby theatre. The master of ceremonies announced a dance number and the musicians started to play. But the dancer was delayed and didn’t make an entrance. Whereupon Sheree arose from her seat, climbed up onto the stage and began to rock and roll. The audience applauded wildly. But June Bethel cried, “Horrors!” and hid her eyes with embarrassment.

“After that Mother decided I needed val dancing lessons as an outlet for my energies,” Sheree says, “so I was enrolled at the Falcon Dance Studios. There wasn’t any money for this, so Mother and I did odd jobs of painting and sweeping out to pay for the lessons.”

Sheree loved the hours she spent at dancing school and never missed a lesson. She studied ballet, tap and acrobatic dancing. She even took fencing lessons for rhythm and muscle building.

When Sheree was eleven she was a member of a U.S.O. troupe. They entertained at army camps and hospitals. One time when she was doing a solo number she suffered an accident that would have shaken the composure of a much more experienced professional. But Sheree was quite unruffled she felt her under-panties coming down.

“I was wearing a ballet costume and I was doing a bourrée, which is that series of little quick steps done on the toes. Suddenly I felt the elastic around my waist give way, and then something began to slip. I didn’t stop to look down. I knew what was happening. So I danced right over the wings and off-stage. We were in a hospital neuro-psychiatric ward and of course the guys loved it. They really cheered and hollered. It was good for them.”

Another time Sheree did a high kick and felt a shoulder strap break. She grabbed the strap and held it while she finished her number. Again the applause was deafening, and she learned a valuable lesson in showmanship. After that, such “accidents” become a standard part of her routine. She “lost” hats, wigs, shoes, buttons—anything to keep things lively and interesting.

Two years later, when she was thirteen, Sheree became a real professional. She landed a summer job in the chorus at the Greek Theatre in Griffith Park in Hollywood. “I had to dress up and lie about my age,” she remembers, “but it was worth it.” She earned her first important money, $65 a week, dancing in such musicals as “Rosalie,” “Bittersweet” and “The Great Waltz.” They rehearsed one the same evening. It was hard, muscle-busting work, but Sheree was happy. It was what she wanted.

At the Greek Theatre she had a few accidents, but these were strictly un-planned. One night she led her chorus line on-stage at the wrong time and really fouled up the whole number. Another night she kicked off a dancing shoe that hit a bald-headed man right on his shiny dome. But the time she wore black underpants in a ballet line of thirty girls all wearing snowy white was a topper. “Golly, but that choregrapher was mad,” she recalls, grinning.

During that same summer Sheree fell madly in love. And she says it was strictly wonderful. “Up to that time boys and I had been on a pal basis. I used to play touch football with them over in the vacant lot. A couple of fellows I knew parked cars at the Christian Science Church on Sundays and I helped them before I went in to the service. Later when they got jobs parking cars at Ciro’s, I got in on that act, too. We earned a dollar a night. When the rich people were in dining and dancing we sat in the big, shiny cars and played the radios and made like we were movie stars.”

The object of Sheree’s affection was a lad named Ray Sinatra, son of the orchestra leader, and cousin of Frankie. He was studying to be a brain surgeon. He gave Sheree her first kiss. “We were quite serious for all of a summer.”

School wasn’t the same after that, Sheree says. At the U.S.O. and the Greek Theatre she had felt like an adult and had been treated like one. But now she was just a school kid again, with all the old complexes, fears and insecurities crowding in on her. “I had a crush on one of our football stars, but I was too shy and self-conscious to do much about it. Besides, I discovered that some of the kids looked down on the fact that I had worked as a chorus girl.”

Sheree worked at the Greek Theatre two summers after that and found some happiness in her dancing. Then, when she was fifteen, she met a big, rugged, sandy-haired guy and married him. What happened? Sheree shakes her head. She is reluctant to talk much about it.

“It’s hard to explain how these things happen,” she says. “Can you remember what went through your head when you were fifteen? Well, I can’t either. But there it was.

“I had gone to Hermosa Beach with my girl friend, Donna Matson. She wanted to meet this fellow, but I wasn’t especially interested. Then we wangled an introduction, and right away he asked me to go out with him.

“His name was Fred Bessire and he was working as a draftsman. He was twenty-five years old. I didn’t tell him my age. Our first date was a wienie roast in the back yard. The next night he wanted me to go dancing at the Palladium, but I didn’t even have a pair of high heels. So I went to an outlet store and bought a pair for three dollars. At that price I couldn’t expect to get much of a fit. I squeezed into a pair of four-A’s. After a while my feet began to hurt, but I danced all evening anyway.

“On our third date we went to the Cocoanut Grove. It was very elegant and of course I was impressed and very shy. While we were eating dinner, Fred put a small box on the table in front of me. It was his mother’s diamond ring. Then he asked me to marry him. I said, ‘I hope you know what you’re doing—because I sure don’t.’ But I guess we were engaged. Four months later we drove to Las Vegas and were married.”

How do the Fates decree who shall be happy and who shall be unhappy in marriage? What intricate mechanism of human attraction is needed? What tricky combination of plot and circumstance?

“I was one of the unlucky ones,” Sheree says.

The newlyweds lived for a while with Fred’s family and then with Sheree’s. Later they had their own small apartment. Then, after a few months, Sheree began to have spells of headaches and nausea. She was finally persuaded to go to a doctor. He listened with a stethoscope, punched, prodded, counted and made some tests.

“Well, young lady,” he said, “congratulations! You’re going to have a baby.”

Congratulations? Here the two kids had run off and got hitched over a quick weekend, and now they were going to have a baby before they were barely started. And long before Sheree had realized that such things could happen to anyone as young as she was. Was that noise you heard the sound of plot and circumstance in motion? Or was it the Fates laughing at them?

Sheree’s baby was born in a maternity home, where no anesthesia was used. It wasn’t easy for her; she suffered terribly. “I was. frightened very much,” she now says. But finally little Dawn arrived, cooing and gurgling, with great big eyes just like her mother’s.

Yes, the Fates were laughing at them, and it was sardonic laughter. For the marriage broke up right after that. And Sheree, in addition to her own problems of survival, now had a child to care for and support. Six weeks after the baby was born, Sheree was dancing again, to earn a living for her daughter and herself. And she was only sixteen years old. Remember? How tough can it get?

“I worked in several night clubs around Hollywood,” Sheree says. “I left the baby in Grandma’s care and did two shows a night, three on Saturdays. At the Florentine Gardens I often took the baby with me. She was a lamb, never a bit of trouble. She slept in a hat box. We lined the box with fans, the ones we used in a plush production number, so Dawn was warm and snug. I had a small iron I took to work with me so that I could press out her diapers.”

When Nils T. Granlund, the m.c. at the Florentine Gardens, made up a show to play the Flamingo at Las Vegas, Sheree went along as line captain, specialty dancer and assistant choreographer. Before the opening, she drove up with another girl, Jane Parrish, and Dave Gould, the choreographer.

“We were all dressed up in our best,” Sheree says, “because the hotel people wanted us to make a sort of entrance to publicize the show. Dave was driving an old sedan and in the back seat we had all the costumes and shoes and music for the show plus our own clothes. Twenty miles from Las Vegas, right out in a stretch of sand and nothing, the car caught fire. We tried to beat out the blaze with rags. We threw sand on it. Finally we pushed it so that it wouldn’t blow up. Then a truck came by with a fire extinguisher. After that we needed a tow into town. At the garage I reached into the trunk compartment and the top came down and knocked me out cold. They took me to the hospital and X-rayed me to see if anything was broken. Nothing was, so I finally drove over to the Hotel Flamingo. But by that time I was in no condition to make much of an entrance. I went to my room and crawled into bed. But I didn’t get much sleep. I had barely dropped off when the walls began to shake and tremble. I thought it was an earth-quake and rushed outside in my night gown. Then I learned that they had just set off an A bomb. Man, that was a climax I’ll never forget!”

Sheree stayed at the Flamingo nine months, earning $175 a week. That was top money for her and she returned to Hollywood with a savings account. But it didn’t last long. Then she was back at the old grind again, eking out a meager living doing kicks and time steps and smiling at the customers.

“Between night-club jobs I did some modeling,” she says. “I did a fashion show at the Shamrock Hotel in Texas and I went to Las Cruces, Mexico, to pose for some advertising photos. Once when I was hung up for money, I made some short dancing films. The photographer was a nice guy and his wife was, too. She always asked about the baby. They paid me fifty dollars the first time and one hundred dollars for each of three times after that. Later somebody tried to prove that the films were indecent and not to be sent through the mails, but the Judge threw that out of court. He said there was nothing naughty about them at all. Personally I thought they were rather dull.”

Sheree was dancing at a Santa Monica bistro called the Macayo, for $42.50 a week, when she decided to give it all up and get a steady job as a secretary. Then came the sequence of events that rocketed her to star billing in Hollywood. She played in “Hazel Flagg” on Broadway and then came to Hollywood to make a movie with Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis. On the Paramount lot, she met Bing who offered her a spot on his tv show. And her sensational dancing there made her one of the most talked about personalities in Hollywood. After that came her contract at 20th and her first picture, “How to Be Very, Very Popular.”

Now that she has moved into her new home, Sheree is relishing her newfound peace and tranquillity. She doesn’t go out much. She says, “It’s fun to stay home.”

She can sew, and she enjoys making her own clothes. She can cook, too, being especially good at pineapple upside-down cake and Hungarian goulash. She keeps fit by swimming and playing tennis. She is learning to play the recorder. And she spends many hours playing with Dawn and listening to her lessons. “I want her to grow up as normally as possible. She seems to have a good healthy interest in a good many things including herself. I am hoping that she will not be interested in show business.”

What about love, Sheree?

“Sure I want to get married. I’ve got a real healthy attitude towards marriage—no blocks at all. I want a husband and Dawn needs a father, and I’m looking forward to the day when we can have both. But that’s for the future. After all, love is something you can’t make plans about.”

On the set Sheree is her usual merry self. She kids with everyone and has a ball. One time an interviewer asked about her favorite authors, and she flipped, “I can’t decide between Webster’s and Funk and Wagnalls.”

About bop talk she says, “I’m putting it down.” But in spite of herself it seems to crop out. When a friend admired a trench coat she was wearing she said, “Yeah! Mickey Spillane laid this on me.” And about her success in the movies she murmurs, “It’s the real jazz!”

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE SEPTEMBER 1955