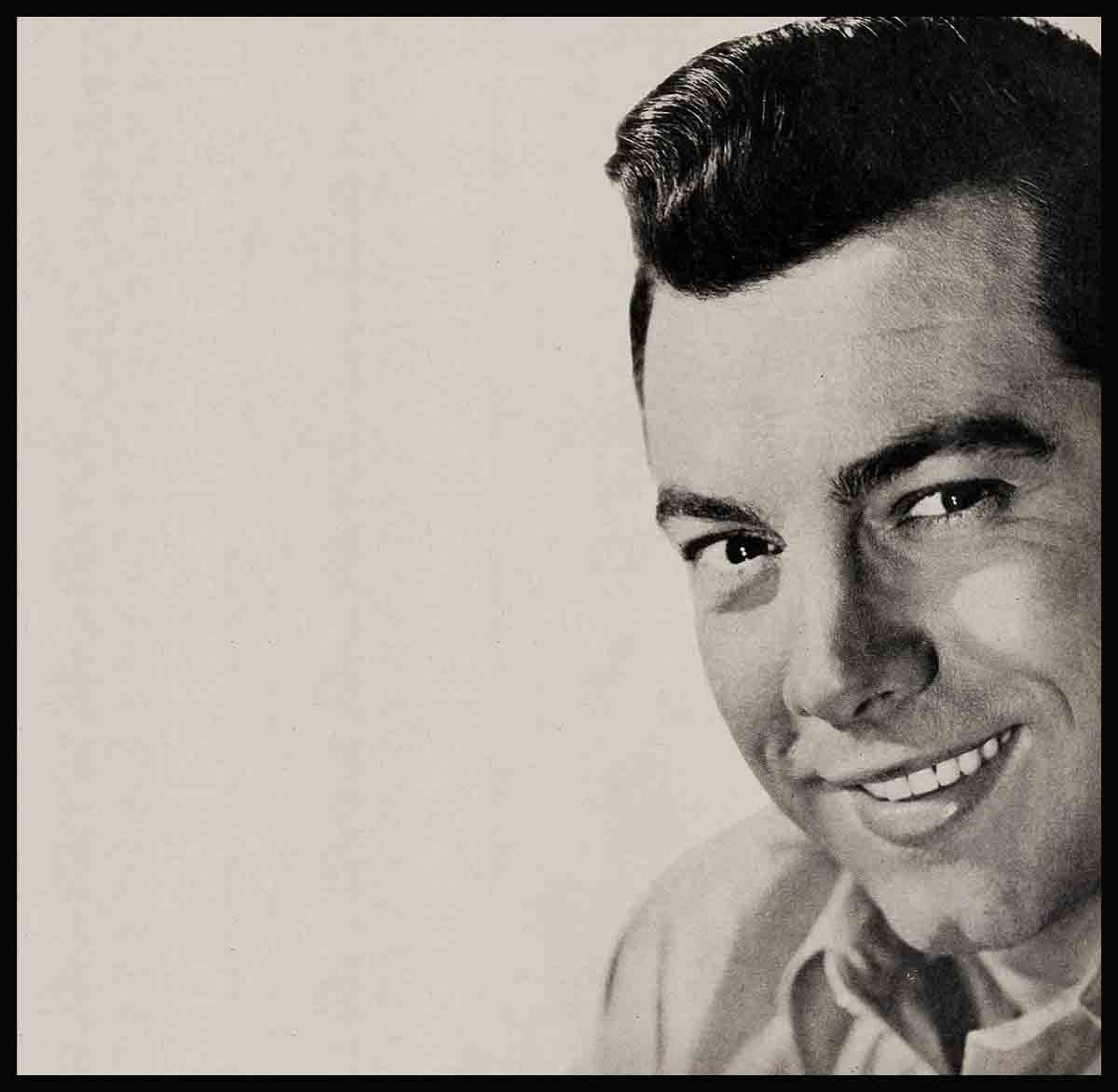

Mario Lanza Fights Again

Ever since MGM signed him to a contract, Mario Lanza had proven himself a thorn in the corporate flesh of Loew’s, Inc., a hundred million dollar holding company which owns and operates the studio.

According to executives, Mario has fought with directors, writers, producers, makeup men, musicians—practically every department on the lot.

He has argued with Dore Schary who runs the studio, tussled verbally with little Joe Pasternak, his producer, complained vociferously about the choice of musical conductors, commented acidly on the studio’s insistence that he cut down on his weight.

In short, Mario in the past three years has earned the reputation, either justified or not—it all depends on whose side you’re sitting—of being MGM’s bad boy. He is at this writing the enfant terrible of Hollywood, the tantrummental star whose moods and outbursts have brought down upon his head the same type of censure that a few short years ago was meted out to another unstable star, Judy Garland.

The long-simmering feud between Mario and MGM reached the boiling point in August of this year when the studio decided that it had taken all of Lanza’s shenanigans it was going to take.

Mario was put on suspension for failing to report for the start of The Student Prince.

This film was scheduled to get under way on Monday, August 18th. Mario had already recorded the musical numbers, and absolutely no trouble was expected.

Came Monday, however, and Mario refused to report to the studio. Someone suggested the possibility of the tenor being ill. Inquiry was made and Lanza’s health was reported as excellent.

Came Tuesday and again Mario didn’t show. The studio legal department sent telegrams, special delivery letters. Still no Lanza.

On Wednesday Mario was again conspicuous by his absence. This time the studio executives blew their collective top. Mario was suspended, taken off salary, and the studio announced that legal attempts would be made to force Lanza to pay for the damages his failure to appear had cost the studio. At the same time, however, reporters were given to understand that if Mario showed up for work Thursday morning, all would be forgiven.

Thursday morning Lanza did not set foot in Culver City and all hallelujah broke loose.

“Who the devil does he think he is?” shouted one executive, “God?”

“Insofar as I’m concerned,” blurted another, “he’s through, finished, washed up.”

“I don’t care if he’s the greatest box office attraction in the world,” said a third. “I think we should tear up his contract, give him his release and throw him out. He’s not worth all the aggravation and heartache.”

The reason for this condemnation is money. When a motion picture is scheduled to get underway, the studio must pay the salaries of all the people who report for work. It already has spent thousands of dollars in set construction, in costumes, in music arrangements and so forth.

When Mario did not report for The Student Prince, MGM had to pay everyone else who did, despite the fact that no one could do a lick of work without Lanza.

“Look,” one production man explained, “we borrowed Ann Blyth from Universal for this picture. Jane Powell was originally set for it, but she got pregnant. The studio must be paying Universal at least $50,000 for Blyth. Then we have to pay the rest of the cast, Gig Young, Janice Rule, Edmund Gwenn, Walter Hampden, Florence Bates, Leo Carroll, and the whole crew. I don’t know the exact figures, but I would say that Lanza’s failure to show up this week has cost the studio anywhere from $75,000 to $100,000. Now the cost of preparing a film like The Student Prince is around $600,000—that’s before an actor even steps on the sound stage. So that if Lanza doesn’t make this picture, the studio can sue him for around three quarters of a million.”

Joe Pasternak, the small, shrewd, sagacious MGM producer who knows Mario as well as any man in Hollywood, told me, “I understand Lanza, and I can tell you that we’ll have this picture finished before your article even gets into print, and Lanza will be the star. This boy has problems, you know, like the big trouble with his business manager. This boy forgets he has responsibilities. A couple of days go by, then all of a sudden he remembers he has a picture to make. By the time he remembers, hell has broken loose. I’m sure that Mario Lanza will be the star of The Student Prince.” Mario undoubtedly will be, but the studio in the future is going to regard him with a jaundiced eye, because these are the days in Hollywood when, because of the inroads of television, stars must cooperate. The pampering days are over.

A few months ago, for example, June Allyson didn’t want to make Woman In White with Arthur Kennedy. The studio said they would sue June for the preparation costs, almost $300,000. Little Junie changed her mind in a hurry.

This July, June also let it be known that at long last she and Dick Powell were going to vacation in Europe. The studio called June in and told her she had been scheduled for Battle Circus and Remains To Be Seen. June quickly cancelled her steamship reservations.

Similarly, Ava Gardner was notified by the studio this past summer that unless she began to cooperate she would be kept on suspension, off-salary until her contract expired next year. Seemingly overnight, Ava had a change of heart. She agreed to star in Vaquero and then go to Africa for Mogambo with Clark Gable.

One of the few stars who still insists upon the exercise of temperament is Mario Lanza. He just won’t realize that time is money, or realizing it, he doesn’t particularly care to put himself out.

Here, for example, is a recent item from a trade paper about Mario: “RCA was set back about $10,000 by Mario Lanza last week when, after some 80 musicians had assembled at 8 A.M. on a Republic sound stage for a day’s recording of MGM’s Be My Love score, word came from Signor Lanza in mid-afternoon that he wasn’t feeling well and wouldn’t show up that day at all.”

Mario’s three motion pictures have grossed about $12,000,000 to date, admittedly a lot of money. Lanza, therefore, is in the strategically advantageous position of being one of MGM’s top breadwinners, but by the same token it’s the studio that has made Mario world-famous. The studio also controls his radio rights, and if Mario doesn’t behave himself, he will have no radio show.

Why shouldn’t Lanza behave himself? Why shouldn’t he report for work on time? Why must he carry on like a big baby? These are the questions everyone in Hollywood wants answered. They know that basically Mario is a kind man with a deep and genuine love of people. His good deeds, his charities are legion. No need to repeat them here. Everyone knows about the little girl from New Jersey he flew to California and how he virtually gave her new life, new hope for living. Everyone knows about his contributions to orphanages, his loans to struggling musicians, his subsidization of composers, his championing of the underdog.

But why, in the face of all this, does he act like a spoiled, irresponsible prima donna?

Some people say it’s because he is a genius, that he’s different from ordinary folk, that to expect him to act as most of us do is to make no allowance for his extraordinary ability.

“Look at Caruso,” a friend of Mario’s points out. “Who could control him? He had a dozen illegitimate kids. He was always getting into hot water. One minute he was gay, the next minute sad. Opera managers accused him of being mad, intractable, irresponsible. They couldn’t figure him out, just like Mario with this Student Princeepisode. No one knows what’s in his head. Only last week Mario went up to Eddie Mannix. He’s the general manager of the studio. He apologized to Eddie for everything, swore that he’d turned over a new leaf. So what happens? A few days later they start a picture and he doesn’t show up. Why? He likes the songs, he likes the script, he likes the cast, he likes the director. You can’t figure a genius out. When a man is a genius, you’ve got to play along with him. His idiosyncrasies must be overlooked if you want to use his talent.”

Lanza’s genius as an excuse for his questionable behavior is open to doubt, since many music critics insist he is no genius at all, merely the possessor of a powerful set of vocal cords.

The more reasonable explanation for Mario’s conduct lies in the undeniable fact that he’s had many problems to face.

Number one is the problem of money. Up until a few months ago, Mario never worried about money. He had a business manager, Sam Weiler. Sam was the real estate operator who backed Mario financially when Lanza came out of the Army and decided to study in New York. Mario had no money at the time, and Sam subsidized him to the tune of $50,000, paying for his rent, clothes for him and his wife, food, shelter, etc.

Mere signed a contract with Weiler giving him 20 per cent of his gross earnings. When Mario came to Hollywood, Weiler hired the Music Corporation of America to represent his protegé, paying them ten per cent of his twenty. Weiler, however, looked after Mario’s taxes, expenses, bills, record royalties—everything that had to do with money.

Mario was given $20 a week spending money and very rarely spent that. Anytime he and Betty wanted to buy something they bought it and signed a charge slip.

Lanza has earned close to $2,000,000 in the past three years. This spring he decided to see exactly how much he was worth. He had a new recording contract coming up with RCA, and he wanted to find out how his recordings had done in the past.

Mario took a look at the books. He couldn’t believe the figures. It seemed almost impossible. He looked again. The truth was staggering. After taxes and expenses, he had very little actual cash to show for three years of constant work.

Mario-and Sam Weiler had several conferences. The publicity was extremely guarded, but once these conferences were finished Sam Weiler took off for a vacation in the Poconos. Two weeks later, the news was out. Sam Weiler was no longer Mario Lanza’s manager. Mario was looking after his own money—what little of it he had left. Surprisingly little!

Mario is the first to say how greatly he is indebted to Sam. He will tell you that Sam is a man of probity, sagacity, and unblemished reputation. But, even so, Mario was stunned when he learned how much of his earnings had gone to the Government in taxes, how much he’d spent in expenses.

The Lanzas have also had help trouble. For years they’ve boasted of a wonderful, efficient couple, Johnny and Thomas. A few weeks ago a relative died leaving the couple a prosperous business. Mario told them to take it over and run it, but they were reluctant to leave the Lanzas. “Go ahead,” Mario insisted. “It’s the chance of a lifetime.” The couple moved out, grateful for Mario’s advice.

Thus for weeks now, the Lanzas have been without help. When you have two little children in the house and a pregnant wife, that can be a strain, especially when for years you’ve been waited upon and even served breakfast in bed.

Things haven’t been going too well for Mario Lanza of late.

Just remember that next time you read about his temper and his tantrums, his foibles and his fights.

Underneath it all, he’s a very nice guy or, as his wife once confided to intimates, “a big, sweet baby who must be handled with kid gloves.”

(Mario Lanza can be seen currently in MGM’s Because You’re Mine.)

THE END

—BY CAROLINE BROOKS

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE NOVEMBER 1952

No Comments

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.