The Day A Marriage Died—Judy Garland

Just look this way, Miss Garland. “Smile, Judy. “How about one standing up?” “Raise your hand and wave, Miss Garland.” “Now sit down and look in the mirror, Judy.” To her, the voice of the newspaper and magazine photographers sounded far away and blurred, as if they were all talking under water. But Judy Garland looked, smiled, stood, waved and gazed in the mirror. “One last question, Miss Garland,” a reporter said. “Are you scared when you first go on stage?”

What? . . . Im sorry. I didn’t hear you,” Judy said. The reporter repeated the question. “Scared?” Judy said, “Yes. But as scared as I used to be? Never. I’ll never be that scared again.”

Judy peered into the mirror, after the boys from the press had left and felt the old stagefright, not the new nervousness, take possession of her mind and body. She was back with Sid, back in his car on Lookout Mountain, looking down with him at the lights of Hollywood. That’s when stagefright had first hit her—the churning in the stomach, the pounding of the heart, the limpness in the arms and legs, the overwhelming desire to run and hide. Crazy, that it had first happened not when she was performing, but when she was sitting next to Sid in the car, with his strong arm around her, cradling and protecting her.

They had driven up into the hills to escape a hot Hollywood night. It was cool in the mountains and they had chatted and laughed together. Everything seemed funny. They talked about their first date: how he had met her at a party and asked her to go out with him, and how she had refused; how she had called him a few weeks later, told him she had tickets to a ballet, which a friend had given her, and asked if he’d like to go; how at the ballet he’d fallen asleep almost immediately and how she’d nudged him awake, and admitted she was bored, too; how they’d left and gone to a drugstore for ice cream sodas and hamburgers.

“Sid,” she said, moving away from him in the car, “I must tell you something. It’s been on my conscience for days, ever since we first went out. Nobody gave me those ballet tickets. I bought them so that I could get you to take me out.”

“I knew it all the time,” he said. “After all, I’m handsome, irresistible . . .”

“You brute!” she said, and kissed him.

“After all,” he said, “I’m not the ballet type. And you—you’re not either; you’re meant to sing. Seriously, Judy, when are you going to sing again? I know you’ve been hurt, confused by things—unhappy. But it’s time for you to sing again. Not on records, not on radio, not in pictures—not yet. But on a stage, in front of people. Maybe in vaudeville. Where you can feel the audience opening its heart, where they’ll love you.”

As he talked, stagefright took hold of Judy. She actually saw the people in the audience. And they weren’t smiling at her. They were looking at her without expression on their faces. And no matter what she did, how hard she tried, they stared at her like horrible statues.

She shut her eyes to blot out those people and pressed her hands over her ears to keep out Sid’s words. Then she sobbed hysterically and clutched Sid desperately. “I can’t,” she cried, “I can’t, I can’t, I can’t.”

“You can,” Sid said softly. “You can, you can, you will.”

Judy turned away from the mirror in her dressing room and looked over at the couch. There was her tramp costume, all laid out for her. She put the old hat on her head, tilted it on the side, and magically she was carried back in time to April 10, 1951, back to London with Sid, back to the Palladium on opening night.

She was exhausted. The night before she hadn’t slept a wink. Back and forth, back and forth she had paced, feeling stark terror, wanting desperately to run. To hide. A hundred times she had started to pick up the phone, to call Sid for help. But something always stopped her. “I can’t let him down,” she had said to herself. “I must go on.” Daylight came. She had gone into the bathroom and thrown up. Room service brought breakfast for her. She had turned green and waved the food away. Then she lost track of time. Somehow she was at the theater. The band was playing. Sid stood beside her in the wings. She was exhausted. She turned to him and said, “I can’t, I can’t. I’m sorry, Sid. I love you but I can’t.”

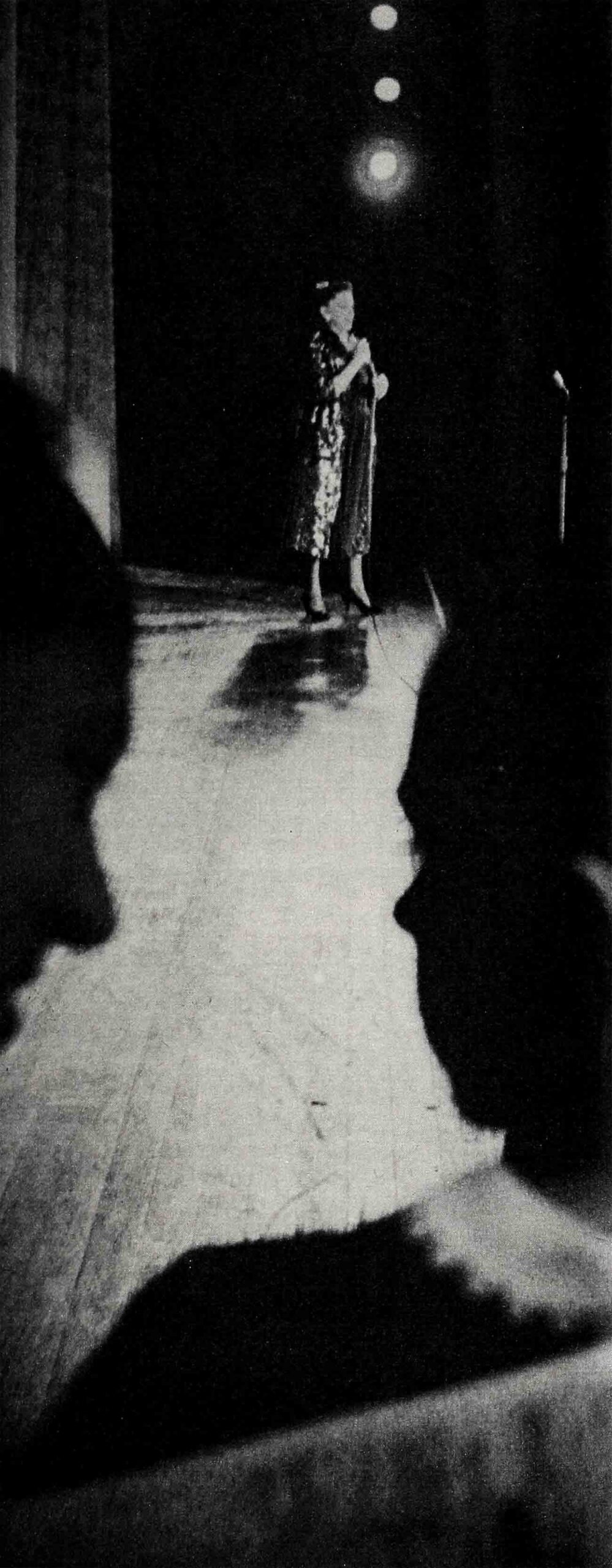

Then Sid shook her so hard she heard her teeth rattle. “Those people out there love you,” he said. “And I love you.” “You can.” And he pushed her on stage.

The lights were blinding. She staggered and almost fell. Then above the pounding of her heart she heard the opening music, and automatically she began to sing the “Trolley Song,” sliding directly into “Come Rain or Come Shine,” and following that, without pause, with “Happiness Is a Thing Called Joe.” She heard applause coming over the footlights, bent forward to bow and fell flat on her face. In panic, she scrambled off the stage. Sid grabbed her and yelled, “You’re great, baby, you’re great. They love you. Listen.” And for the first time she really heard it, the thunder of applause.

He shoved her out again. Now, through the glare of the lights, she saw the people. Not stone statues, but laughing, crying, yelling people, screaming for more. And she gave them more—“Rock-a-Bye My Baby,” “You Made Me Love You,” “Shine On, Harvest Moon,” “Some of These Days,” “My Man.” Finally, she took off the wig she wore in her tramp number, got a towel from Sid and wrapped it around her head, sat on the very edge of the stage—as close to the audience as she could get—and sang “Somewhere Over the Rainbow.” And then her memories of unhappiness and her feelings of fear disappeared. This was the beginning. Next day, the newspapers headlined: “Judy’s born again.”

A knock on Judy’s dressing room door broke her thoughts. Rap. Rap. Rap-rap-rap. Rap-rap. Rap-rap-rap. Sid’s special “Somewhere Over the Rainbow” knock, and she said, “Come in.” Sid entered. A photographer who had been waiting outside to get some shots of her onstage, poked his head in and asked, “Mind if I take one of you and Mr. Luft?” “Just one . . . all right,” Judy answered.

When the photographer had gone, Sid said, “Well, Judy?”

“Nothing’s changed, Sid,” she answered. “I’m sorry.”

“Mind if I watch the opening number?” he asked softly.

“Of course not,” she said, and almost added—but finally said the words just to herself—“I don’t know what I’d do without you waiting and watching in the wings.”

Sid stood up. For a moment he paused behind her chair and his hands lightly touched her hair. Then he left the room.

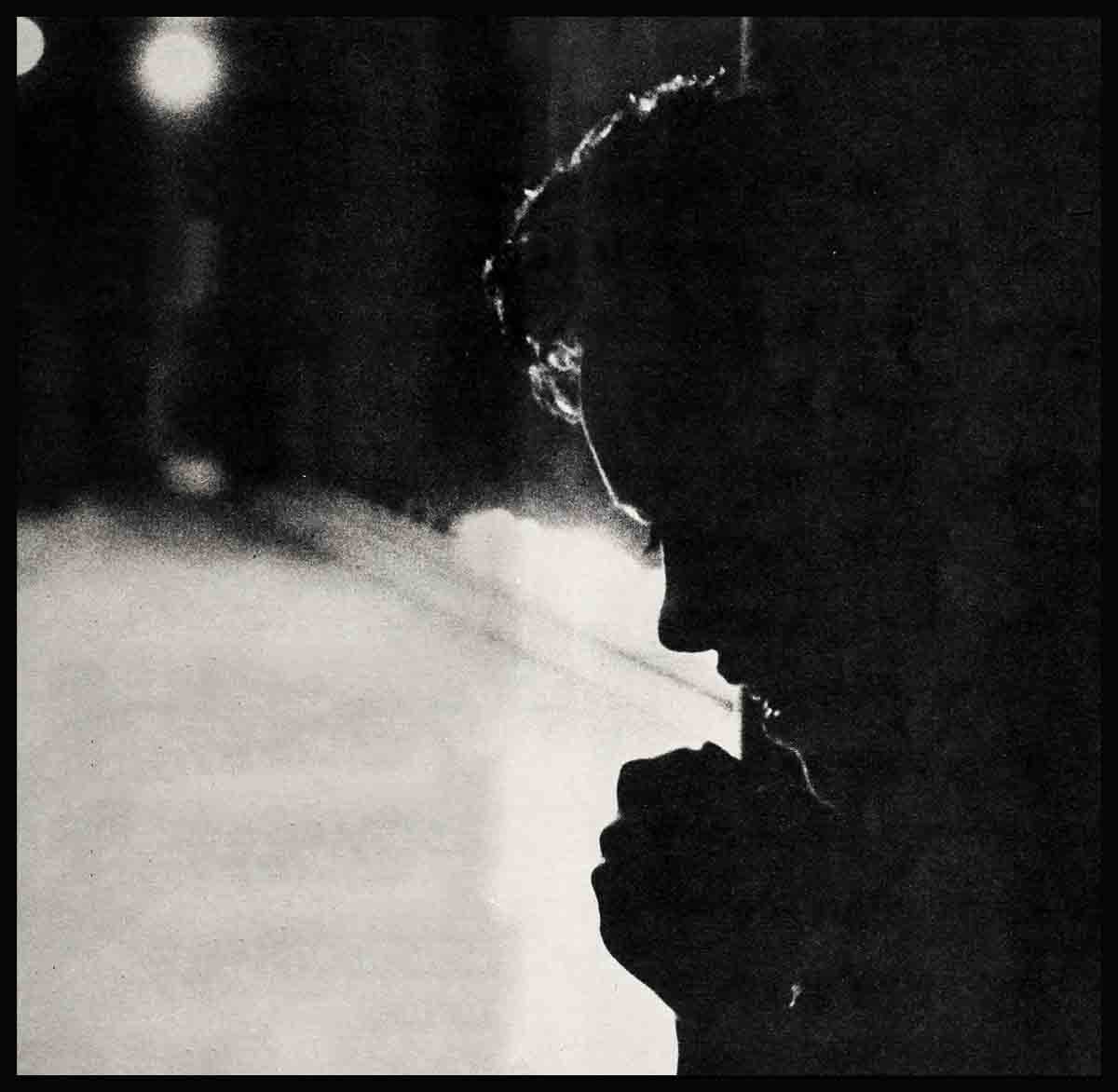

She picked up her silver cigarette case and lit a cigarette. She ran a finger over the inscription on the cover: “Judy, Thank You,” and then read inside the engraved names of all the stagehands and theater staff who had been with her at the Palace back during the winter of 1951-1952 when she had made her American comeback. And then she said aloud, the words she had been unable to utter a few minutes before: “Sid, I don’t know what I’d do without you waiting and watching in the wings.”

Sid had been in the wings, and backstage, and out front, and in the manager’s office, and most important of all, with her whenever she needed him in that mad twenty-week period when she had broken all records at New York’s Palace Theater.

Sure, she had wowed them at the Palladium; sure, she had been a terrific hit throughout her tour of Great Britain. But New York was something else: the tops, the great challenge, the end of the rainbow. And she had been scared. Not petrified like at the Palladium, just plain shivering scared.

And that big-shot at the Palace hadn’t helped. All he did was cry the blues. He skimped and saved on everything. And when she rebelled he as much as told her, “We’re not going to spend money on your show because it won’t last. You’ll flop.” When she asked him for a timpani for her “Get Happy” number, he refused. “We’re not enlarging the orchestra,” he said, “and we’re certainly not adding any instruments. There’s no room for a timpani. Besides, we’d have to take out three orchestra seats to make space for it. Those seats are sold for opening night. And we need every cent we can get before you close.”

So at 2:30 in the morning before opening night Judy and Sid stood alone on the Palace’s empty stage. The musicians had all gone home; the stagehands were filing out. They were talking about the “Get Happy” number and Judy was in tears. “It’s the high spot of the first half of the show,” she said. “Without it, I’m lost. No timpani, no number.”

Sid spied some carpenter’s tools across the stage. He picked them up, went down to the first row of the orchestra and unscrewed three seats. As Judy watched him, a big grin spread over her face. He stowed the seats backstage. Then the two of them went to the phone and called a musician friend in the Bronx. Like two kids on a spree, they hurried to the street and hailed a cab. All the way to the Bronx, Judy sang and Sid made awful noises—“like a timpani,” he said. They borrowed the timpani, told their friend to go back to sleep but to be sure to show up at dress rehearsal that afternoon. Then they returned to the theater and put the timpani where the three seats had been.

“Where will those three people sit?” Judy asked.

“On the stage,” said Sid.

“Of course,” Judy echoed, ‘on the stage.” And they both laughed hysterically.

That night the Palace big-shot flipped when he saw the timpani in the orchestra. But by the end of the first week, when they did sell-out, turn-away business, and even standing room was bringing $7.50 a person, he was smiling.

And when she and Sid got married in Hollister, Calif., on June 8th, 1952, the Palace big-shot sent them a timpani for a wedding gift, with a note that said, “I was a fool. You’re the greatest.”

On stage in two minutes, Miss Garland. “On stage in two minutes,” hollered a voice in the hallway, interrupting her memories.

“Okay,” Judy said, “okay.”

She slipped into her costume, made sure that her make-up was all right and hurried to the wings. Sid was there and so was her daughter, Liza. “Good luck,” he said. “Luck, Mommy,” said Liza. And she was on. After her first three songs, while she paused to acknowledge the applause, she looked over to the side. Sid was gone. Liza was still there. But Sid was gone.

The orchestra started her next number. But she missed the cue and faltered. The leader struck his baton against the music stand and the music began again. Somehow she sang the words to “You Made Me Love You,” and tears streamed down her cheeks and she wasn’t really there. She was back with Sid at the Cedars of Lebanon Hospital on that March night in 1955, waiting for the announcement of the winners of the Academy Awards.

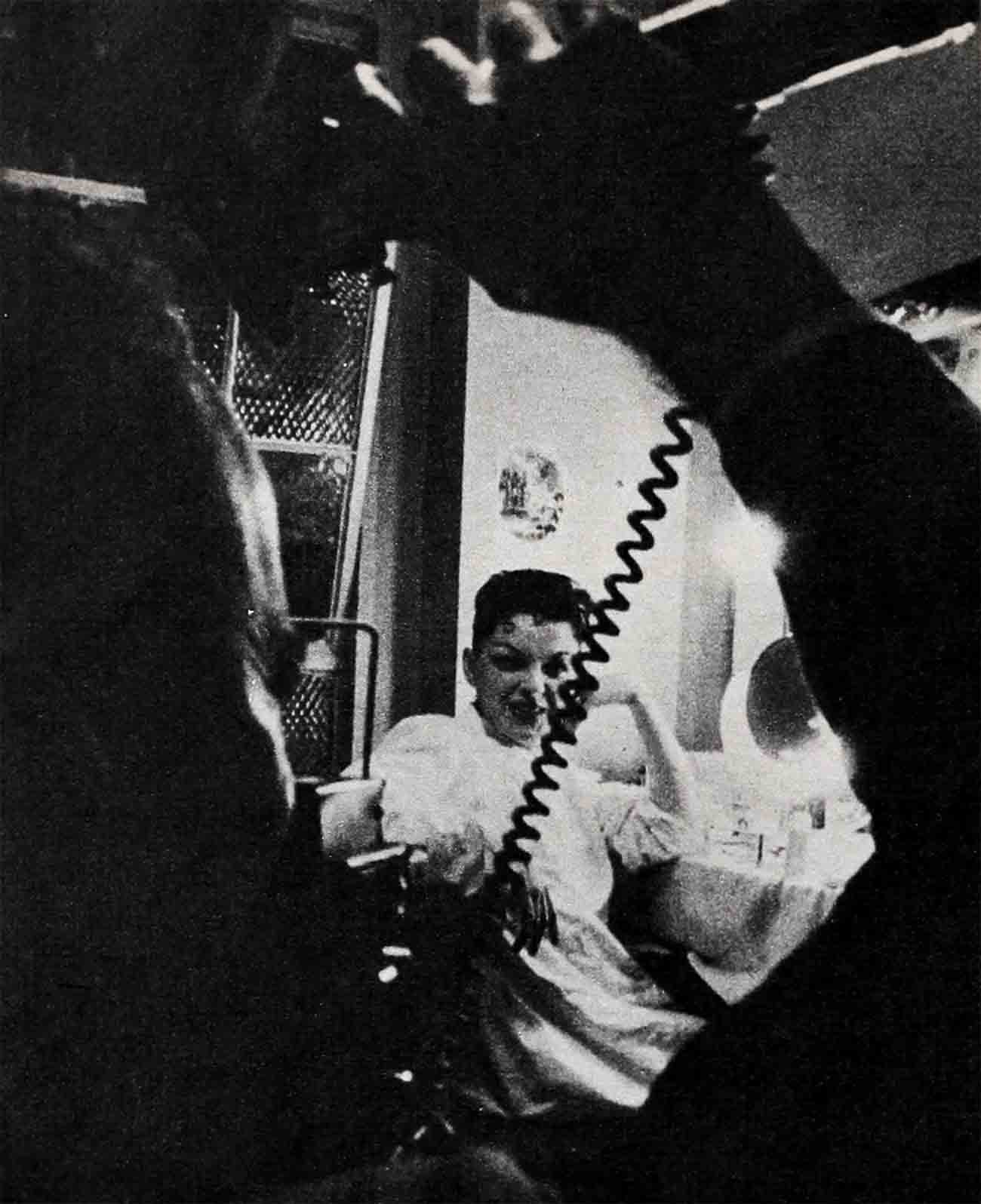

Sid was looking down at her. Although the room was filled with technicians from the TV studio, it seemed for a moment as if they were alone.

“How do you manage to look so pretty after what you’ve been through?” Sid asked.

“Because I’m so happy,” she answered. “Yesterday, when Little Joe was born, the doctors only gave him a fifty-fifty chance. I know. The nurses talked about it. They thought I was asleep, but I heard. But today he’s much stronger. When they brought him in, he howled. That’s good. I know he’ll be okay.”

Sid put a package down on the night table and began to open it.

“What do you have there?” she asked.

“Caviar and champagne,” Sid announced. “To celebrate.”

Judy pointed out the window. “Look at the peeping Toms, Sid.” He looked out and saw a battery of cameras and cameramen, perched atop a four-story-tower built especially for the occasion, focusing on Judy’s room. At that moment the director called, “Stand by,” and Judy and Sid turned towards the three TV sets.

Bob Hope’s face appeared. He announced the nominees for best actress of the year, and Judy smiled when he said, “Judy Garland for her performance in ‘A Star Is Born.’ Then he opened the slip and read: “The winner is . . . Grace Kelly for ‘The Country Girl.’ ”

Judy’s head sank back on the pillow and she closed her eyes. There was a minute of complete silence. Then the TV technicians lugged the sets and their equipment out of the room. The director mumbled and left. Sid and Judy were alone.

“To us,” Judy said, raising her glass of champagne. “To Liza, to Lorna, and to Little Joe. Perhaps I’m not the best actress there is, but I’d rather be the best mother.” The champagne tickled Judy’s nose and she laughed.

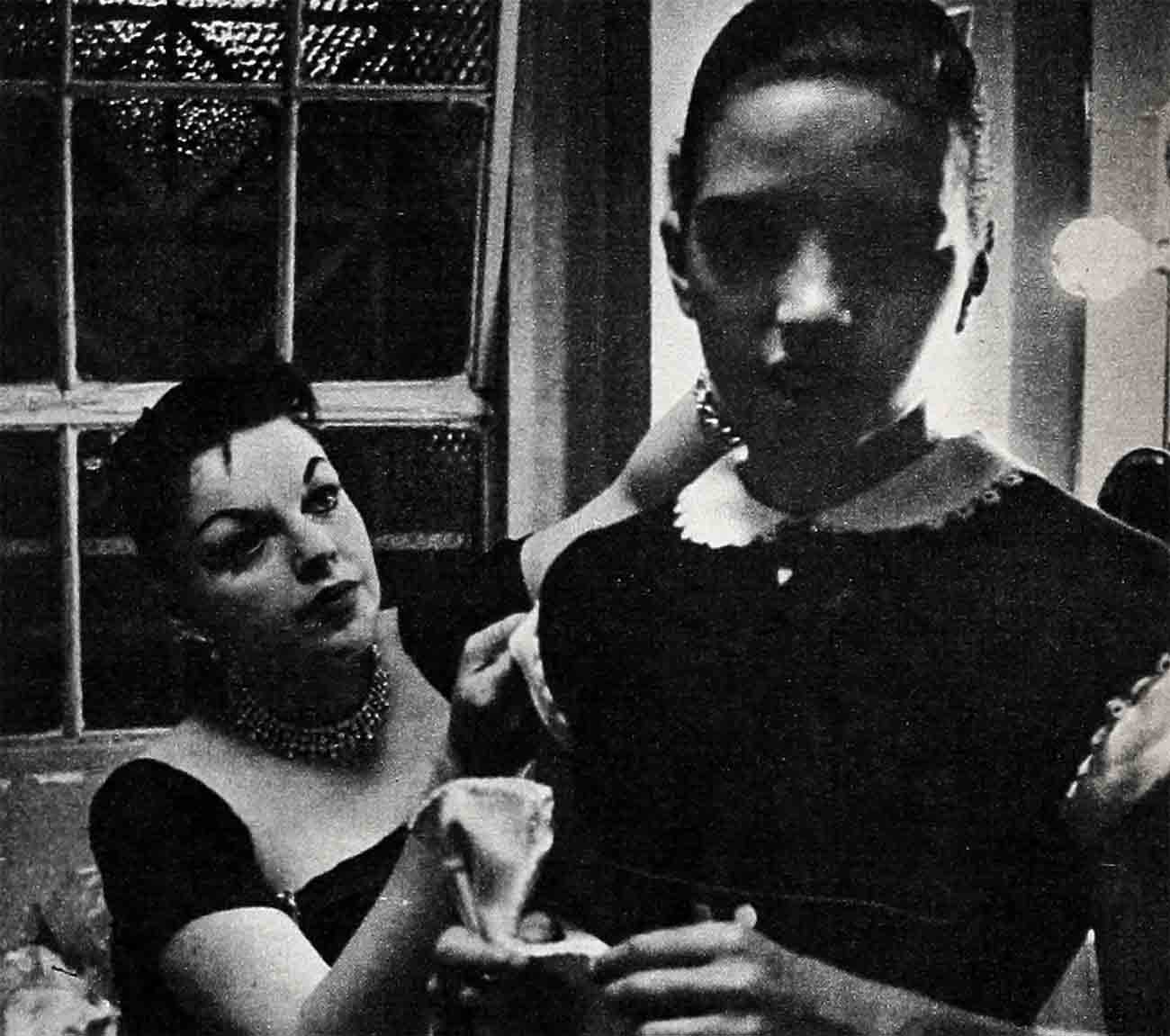

Liza came into the dressing room right after Judy had finished reading Sid’s note. “Mommy, why are you crying?” Liza asked.

“I always cry after I sing ‘Over the Rainbow,” Judy said.

“But you didn’t sing it,” Liza said.

“That’s right, I didn’t,” Judy agreed, shaking her head. “Come here, dear,” Judy said, “let me straighten your hair.” She patted her daughter’s hair in place. Then she let her hands rest gently on the child’s hair, as earlier Sid’s hands had rested for a moment on hers. “Daddy’s waiting for you in the car, dear. He has something important to tell you. I want you to listen and try to understand. Mommy will see you later.”

As soon as her daughter left the room, Judy slumped down on the dressing table and buried her head in her hands. “How will he tell her?” she thought. “What will he say? How will he explain that he won’t be with us anymore, that we won’t all have breakfast together each morning and dinner together each night? Even though Lorna and Little Joe are his kids, and Liza isn’t, he loves her as much as the others. And she loves him. What can he say?”

And pictures and memories of their life together as a family flooded into her mind. She saw every room of their big house at Holmby Hills: The living room furnished only with a grand piano and a ping pong table, on which was Little Joe’s train; the main bedroom with its huge bed, and no clock in the room to remind them of work, and schedules, and duties; the kids’ rooms; the den with its hi-fi set with four speakers, the radio and TV set, the bar, and the fourteen-foot couch. And she saw the grounds outside, with playground equipment and toys strewn all about. But everywhere, in each room and each memory, she saw the family: Liza, Lorna, Little Joe, herself, and . . . Sid.

But then the thoughts of their debts blotted everything else out. She recalled a recent headline: Judy Garland Heads Hollywood Tax Delinquents. She remembered the shame of having to file a bankruptcy petition. She felt the disgust of having to dodge creditors and bill collectors. She knew the indignity of owing the United States Government almost fifty thousand dollars.

Alone in her dressing room, she covered her face with her hands, and let the tears fall. It was too much for her. Too much. Where did the money go? Blindly, she’d lashed out at Sid and his gambling. She’d worked too hard all her life ever to understand the kick others got from it, and it had. been the source of their bitter quarrels—and now, this. But in her heart, she knew it wasn’t that simple. It went back, as long as she could remember. Pouring her heart into her work past physical endurance, while other people signed her name to checks, other people managed her affairs—and, somehow, the fabulous sums she’d earned trickled away. Then, grimly, she got up and dressed. “I must pull myself together,” she thought. “I’ve got to stop this. For the children’s sake. I can’t break down now.”

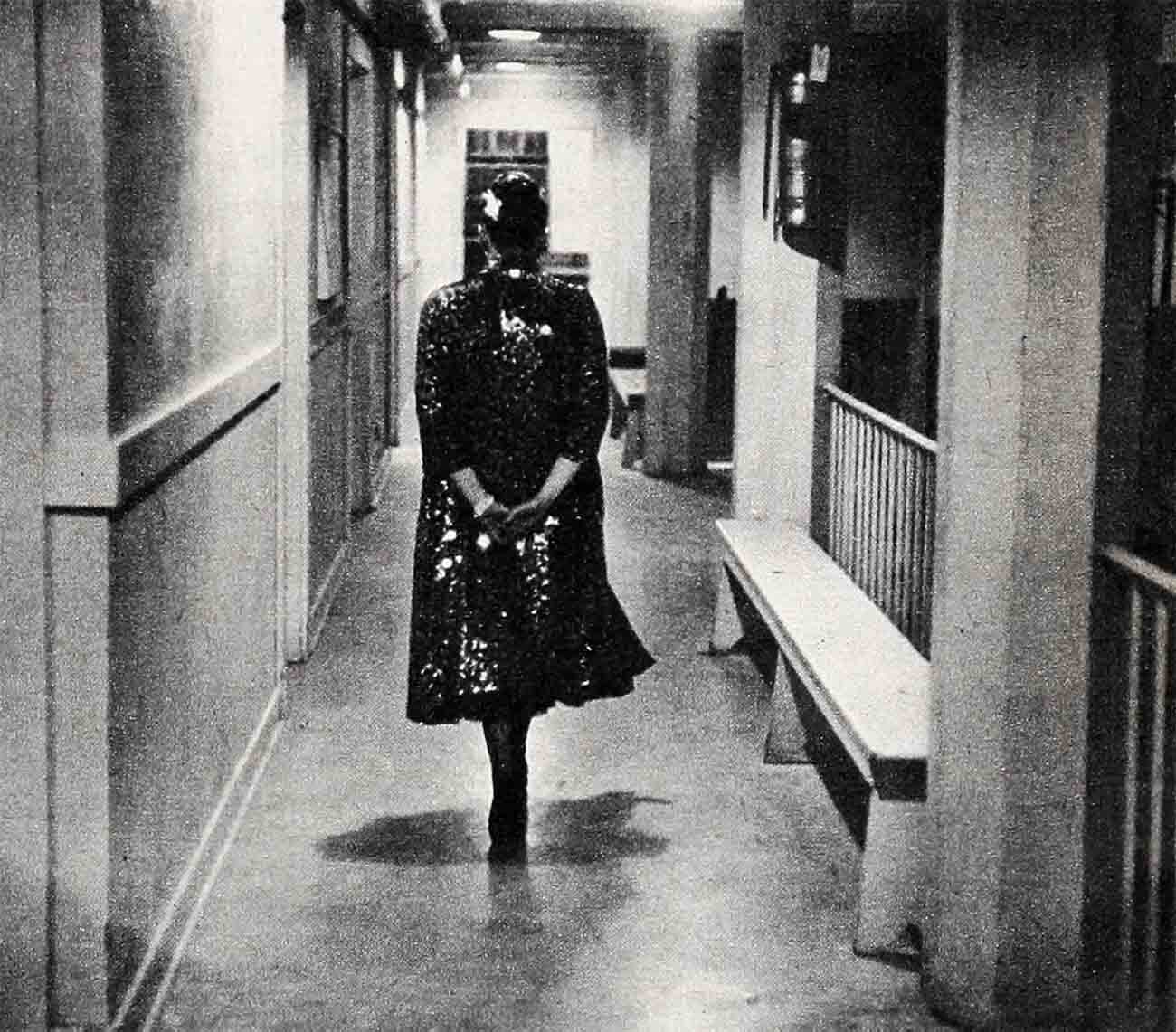

But as she walked alone through the awful emptiness of the deserted corridor, the old. fears assailed her. Fears, grounded in the bitter cruelties of the past, echoing through her confused mind once more: “Look what the studio got stuck with when they let Deanna Durbin go,” “Yow re too temperamental.” “You’re no good.” “You’re too fat.”

“I’ll show them,” she muttered.

Shortly after, she came to New York for an engagement at the Town and Country, in Brooklyn, settling herself and the three children in a house at nearby Neponsit, with guards around it, reportedly “to keep Luft out.” Yet, from the time she arrived, she talked with Sid constantly on the phone. He came east, and stayed at a hotel.

Her opening was as sensational as any she had ever known. The entire audience, applauding madly, gave her a standing ovation.

For four nights, everything was great. Especially the night when Sid came and sat with the children, watching her, all of them together, just the way it used to be.

But away from the audience, it was bad. And getting worse all the time. Bills, bills, bills. New York State and federal liens against her salary for back taxes. The gowns she needed, even food was a problem. Her help, getting wind of the situation, walked out. There were violent squabbles with club owner Ben Maksik over what he claimed he advanced her against her $25,000-a-week salary, and what she claimed he owed her. More squabbles with her agent. And with Sid.

It was more than she could take. She felt crushed, under a staggering load too heavy to bear. The twice-nightly shows were cut to one. She arrived much too late. Her voice began to fail again.

The breaking point came on a Sunday night, when 1,700 people had gathered to see her. She had called to say she was unable to go on, but, prodded by her agent, Norman Weiss, she came—fifty minutes late.

The wave of applause as she walked to the microphone seemed unreal and far away. “Well, here I am,” she said, her voice breaking.

She got through one number, her voice husky. Then the second, every word of it mocking her until she could have screamed—“Life Is Just a Bowl of Cherries.” Trembling, she looked out at the sea of faces, and faltered, “I’m sorry. You’ll have to excuse me. I have a terrible case of laryngitis. I wish I could go on. But I can’t. It doesn’t really matter, though. I’ve just been fired.”

Someone quickly cut off the microphone. She stumbled to the edge of the stage, holding out her arms. “It’s wrong, It’s wrong,” she cried. Then, dazedly, “No. It’s wonderful. It’s wonderful to be here. I love you all.”

Backstage, the quarreling commenced again. There was much shouting, angry charges and counter-charges hurled by Ben Maksik, her agent—and Sid. And she, bewildered and broken, in the middle.

The next day, she faced reporters defiantly. “So I’m broke,” she said. “I’ll get along. I always have. Nobody has to worry about me. Right now, I’m going to take my children, and we’re going to get a good rest and enjoy life. As for my future, there are three pictures I could make in Hollywood. Is that bad?”

But after they left, as she stood alone in the strange living room of somebody else’s house, she shivered. The darkness of the shadows in the room seemed to be closing in on her. The darkness that had begun to fall on the day when she and Sid parted. The darkness, the terrible darkness, she had known before, of being alone.

She clasped her hands, and bowed her head. “Please, God,” she prayed. “Help me. Please!”

THE END

—BY JAE LYLE

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JUNE 1958

No Comments