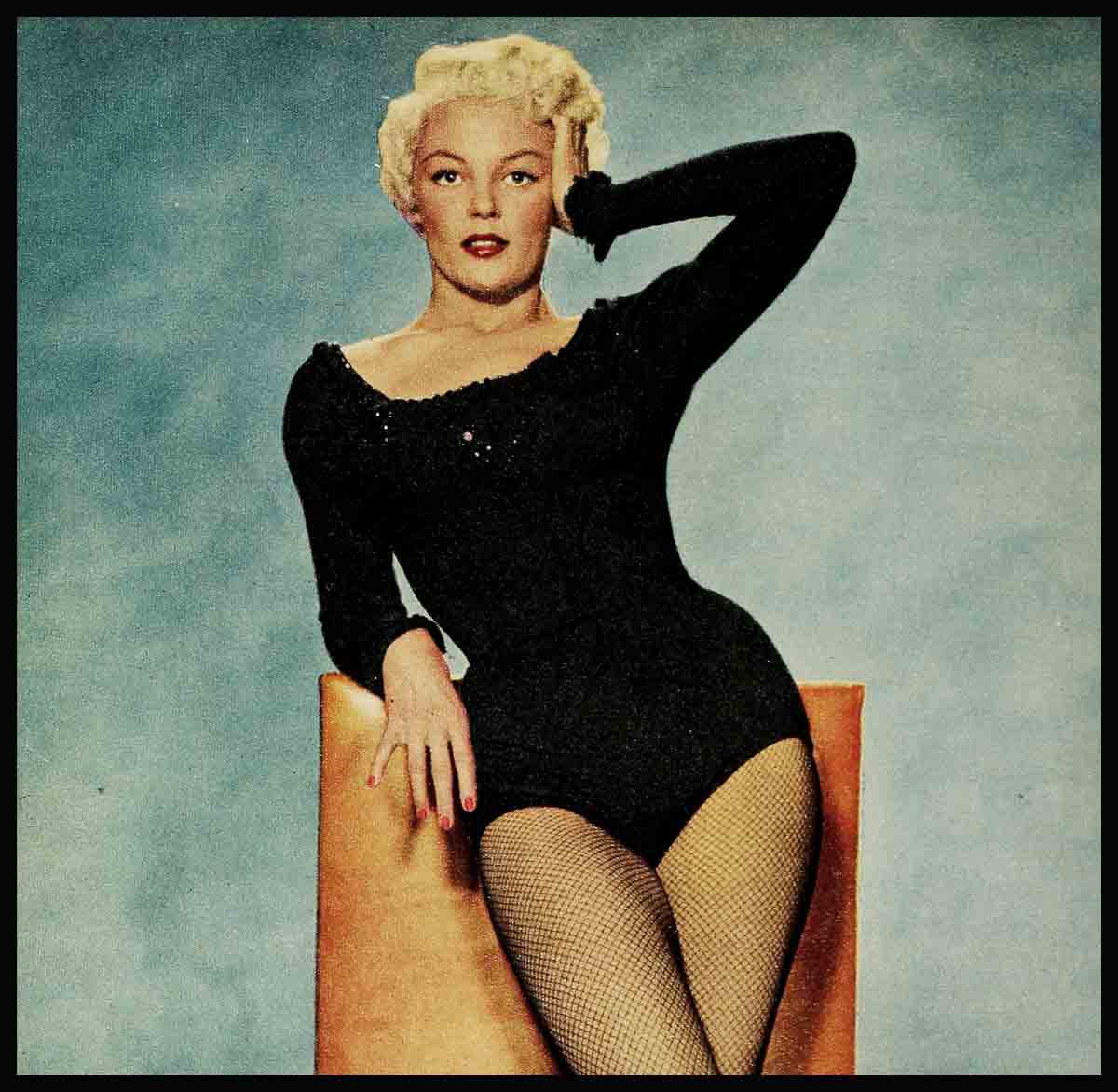

Sheree North

One night, a couple of years ago, a Hollywood choreographer named Bob Alton dropped into a spot called Macayo in Santa Monica, California, for a nightcap. Before he could order his drink, however, something made him yank his elbow off the bar. A sun-bronzed girl with a popcorn ball hairdo and the streamlined figure that Venus should have had was making the floor rock and roll with sensational modern jazz dancing of high voltage.

He asked the waiter to bring her to his table. “I just want to tell you how good I think you are,” he said. “You’ve got a great future in dancing.” The girl gave him a wry grin and her reply had a hollow ring.

“Thanks,” she said, “but my dancing future just passed. This is my last night here. I’m quitting. I’m sick of nightclubs. I hate the noise, the smoke, the late hours, the guys making passes. I hate what people think a nightclub dancer is. Tomorrow I’m dyeing this hair back to brown. I’m changing my name. I’m starting a secretarial course and I’ve got a job lined up at Hughes Aircraft. I’ve been dancing for a future since I was six years old—but it’s all over now. Believe me, I’ve had it!”

The disillusioned nineteen-year-old girl—who called herself Sheree North—could have told him a lot more. That she’d been married at fifteen, for instance, had a baby at sixteen and since her divorce at seventeen had struggled to make and support a home by kicking her legs—without much success and with a lot of heartache and disappointment.

Bob Alton nodded understandingly, although he didn’t change his pitch. How could he? He was a top choreographer with a string of hit shows behind him both in Hollywood and on Broadway. He’d seen discouraged kids like this before, but he’d helped them get their breaks and then watched them shoot to the heights—kids like Gene Kelly, Van Johnson, Vera-Ellen, Cyd Charisse. He knew talent when he saw it and besides, he was preparing a show for Broadway.

“I hope you change your mind,” he said, identifying himself, and talking her out of her telephone number.

Obviously Sheree North did change her mind. She’s still dancing, more senIn fact, right now Sheree is the hottest new discovery in Hollywood. She has a juicy contract with Twentieth Century-Fox and a bright new career ahead. But of course a lot of things happened to Sheree in between.

First, Bob Alton talked her into ditching shorthand for the Broadway show, Hazel Flagg, in which Sheree’s “Salome” dance shook the street from stem to stern. Since Hazel Flagg started from an old Hollywood movie, Nothing Sacred, naturally it came back home as Living It Up—and so did Sheree. Then Bing Crosby, faced with hopping up his TV debut, saw her shake ’em-and-break ’em dance with Martin and Lewis and decided what he could use was a dash of Sheree.

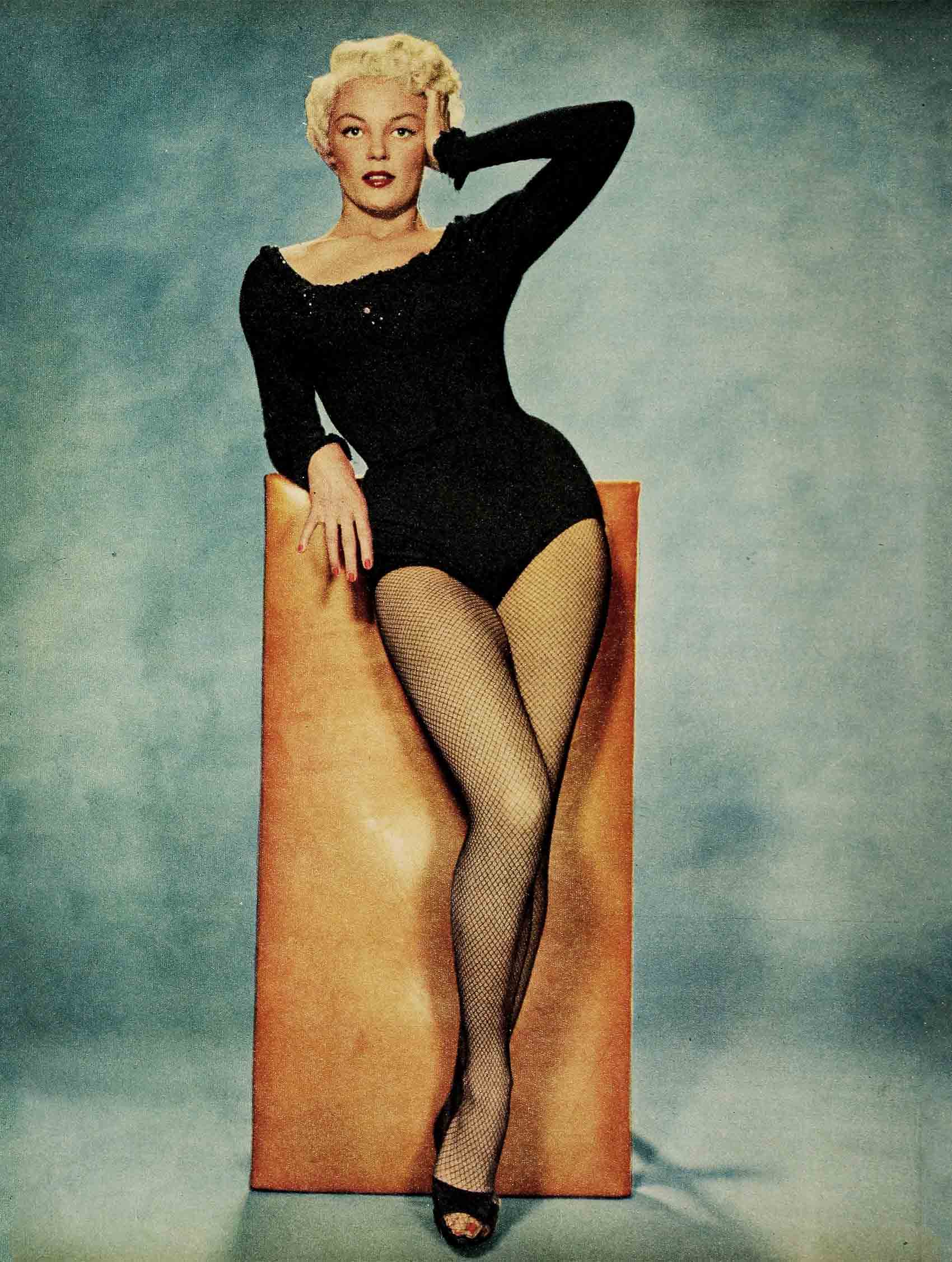

So, one night last January, with practically the entire USA looking on, the North wind blew up a storm. Dressed in a sexy leotard with fringe on the flaps, Sheree steamed up a million screens with movements that could have landed her in the paddy-wagon back when mother was a girl. That night the toll on picture tubes everywhere was terrific. But next day in Hollywood reactions were mixed.

Bing Crosby’s office was swamped with calls demanding to know what ever got under his hairpiece to let a dynamite doll like that steal his show and turn it into a hoochie-cooch. But in the office of an agent named Henry Willson pandemonium of a different sort reigned. Every studio in town was screaming for Sheree. North.

The one which screamed loudest—and bid highest—was Twentieth Century-Fox, for a special and urgent reason: Another sexy blonde had just walked away from Pink Tights to marry Joe DiMaggio and romp away to Korea, leaving an aching, glamourless void.

Dancing or standing “still, Sheree is the type to make old men young and young men glad they aren’t older. She stacks up a perfect 35-23-35 under her platinum mop, tip-tilted nose and chameleon green eyes that change with the weather. Right now the climate is extremely agreeable to Sheree because for the first time in her life she’s got a solid future for herself and some home life with her baby girl. She never dreamed her legs would bring all this about, and she wears an expression of permanent surprise about what’s happened where. Because Sheree has been around Hollywood for a long, long time. She was born there twenty-one years ago last January 17, in an apartment on Heliotrope near Melrose, almost in the shadow of Paramount studios. That was just as the sun was cracking through in the east.

“I guess that’s why Mother named me Dawn,” says the girl who started life as Dawn Bethel. There are other family matters, too, that Sheree has had to guess about all these years. Her father left her mother before her arrival and Sheree still doesn’t know what her dad looked like, where he came from, what he did for a living, or even his first name.

With no father to guide her and the Great Depression at rock bottom, little Dawn Bethel didn’t cut her teeth on a silver spoon. Her mother, June, had to work hard to support Dawn and her half-sister and brother, Janet and Don. Luckily, June knew a trade—jewelry appraising and designing. But there weren’t many loose jewels lying around back in the Thirties, so she pieced out with practical nursing. At times they lived on relief.

Dawn and the other kids were left in the charge of her Grandmother Shoard, a doughty Scotchwoman. Keeping track of three scampering kids around Hollywood was enough to force any elderly lady to her wits’ end, but Dawn complicated matters by changing her name almost every week. Because Dawn and brother Don resulted in household confusion, her ma fastened “Shirley Mae” to her youngest, who promptly rebelled.

“Even as a kid I thought that name was strictly from Dixie,” groans Sheree, “so I tried a lot of others. It drove the teachers at Melrose Elementary School wild. They used to call home and ask if I had a split personality.” Sheree re-christened herself “Cookie,” “Emma” and “Bubbles” and a dozen more before she finally hit on Sheree North, which she likes best of all. “It just sort of sounds like me,” she says, “and it’s simple and easy to say. To date, nobody has associated her chosen name with the Arctic regions, either.

But, by any name, it would take a seventh son of a seventh son to predict that the skinny, eternally sunsuited, barefoot tomboy would ever grow up to dance right in when Marilyn Monroe swished out. A better guess would have been that she’d replace Tarzan. “Cookie” Bethel was rough, tough and hard to bluff. At five she used to shinny up the parkway trees and leap on the backs of surprised passers-by, scaring them silly. The cops around the Hollywood precinct soon knew what a distress call from Avocado Street meant; that snub-nosed Bethel kid had run off again. Usually they found her before midnight, off on some harmless adventure. eu one time they took her to the station house.

That was when her cousin Harold got an Indian tepee for his birthday and decided it was so beautiful he’d just live in it. Sheree went along with the idea enthusiastically, swiped some frankfurters from home and trooped off into the Hollywood Hills to change residence. Things

were going swell up in the brush. They found a dinky cave and pitched’ the tent nearby. A campfire was roaring and the weenies were sizzling. “Some old square who lived down below spotted us,” Sheree hobos going to break in his house and called the cops.” A squad showed up with sirens and searchlights and apprehended the squatters, who knew from their favorite gangster movies just what to do.

“Don’t squeal!” hissed Harold.

“Me—sing?” shot back Sheree scornfully. So there was nothing to do but haul the tight-lipped pair down to the pokey and book them. Hardly had that escapade blown over before Sheree was in hot water again. This time she saw a cute Pekingese dog that belonged to a lady down the block, whistled it home and kept it. This brought the law down again, but Sheree wasn’t cowed. Instead, with a curious sense of justice she rounded up her gang and picketed the rightful owner’s house with signs which read, “UNFAIR TO CHILDREN AND DOGS.”

After a run of episodes like those Mrs. Bethel grasped at any sort of straw to reroute her daughter into more ladylike channels. Sheree’s artistic debut was nothing sensational; she was a blackbird in a pie at a grade school affair. (Sheree’s platinum hair, by the way, is strictly out of a bottle—the real stuff is coal black.) Even that tiny taste of applause gave her ideas. It got so they couldn’t take her to any kind of show because she’d break loose and join the act. Embarrassed, her mother offered to arrange dancing lessons if she’d lay off that sort of thing, and at six, she enrolled in the Falcon Dance Studios in Hollywood. There Ralph Falconer and his wife, Edith Jane, spotted talent and taught her to dance—even though Sheree and her mother had to paint, wax floors and help sweep out the studio for tuition. She never missed a lesson, hiking there after school and sometimes hitch-hiking because the Bethels moved all around. By the time she was nine, Sheree was sharp as a tack on ballet, acrobatic, eccentric and tap. Then, in the USO troupe which Edith Jane organized, Sheree sprang a sensation.

For her first bit of something for the boys Sheree danced out on a slippery floor in a skimpy costume, pirouetting daintily until her feet suddenly flew out from under her and she lit on her tummy. When she got up the straps holding up her costume had snapped. “I sure got a lot of applause,” grinned Sheree.

After that it was amazing how many times little Sheree North had trouble with her costume. Petticoats would fall off, straps snap or buttons pop. Since Sheree was all of ten it was strictly innocent, and, she figures, part of her war effort.

Losing her tutu (little ballet skirt) became the inevitable finale of her dances and it always brought down the house.

All this time, Sheree progressed through a normal course of schooling although it was here and there. In fact, before she left at fifteen Sheree rattled through five public schools and three private ones. This was because her home shifted, but also because Sheree had individualistic ways. At Hollywood High instead of demurely knitting on the gym steps with the rest of the girls, Sheree chased out on the football field and tried to play halfback. The principal didn’t approve of that at all and Sheree’s stay there was brief.

Her mother’s growing jewelry clientele put the Bethel family on a slightly easier street after a while but throughout her girlhood Sheree North had to rustle her own spending money. Her uncle taught her to drive his truck when she was eleven and not long after Sheree was helping a Sunday school boy friend to park cars in a lot near the church. Activities branched out to the Sunset Strip, where the movie stars played at night so Sheree gunned their cars around at the Trocodore and Ciro’s for a dollar and a hamburger a night. “I was nuts about Robert Taylor then, and I always hoped I’d see him there,” she sighs.

But Sheree made her first big money with her dancing. In her thirteenth summer she decided she was ready to be a professional, but the child labor laws stated otherwise. She didn’t let the technicality stop her. With $65 a week at stake, Sheree put on high heels and bought a fake hair fall. Between those two props everything was already convincing. Even at thirteen Sheree was something to see.

So, even though the heels did wobble and the fake hair tumble off when she auditioned for dance director Val Rassette at the Greek Theatre in Griffith Park, he gave her a job. The first night of Rose Marie he thoroughly regretted it.

“I was leading a line of Indian maids leaping out from one wing, to meet a line leaping out from the other,” recalls Sheree. “We were supposed to pass each other, but instead I hit them head on. Everybody fell over everybody else. It was a mess. I don’t think Mr. Rassette was very happy about it.” But Sheree got a steady chorus girl job at the Greek Theatre for the next three summers. The money she made paid her tuition at fashionable Marlborough and Greenbriar schools— with an assist from unemployment insurance.

But she still roller skated home to lunch from work; that is, until a girl friend named Donna bought an old Model-T Ford. They shared the heap’s upkeep, and collaborated on reconditioning. Yep, Sheree’s a mechanic, too, although she admits, “We sure had a rough time getting the drip-pan off.” But once they got the car rolling drastic events followed.

Until she was fourteen Sheree managed to keep free of boy problems. For one thing, she was plenty busy and also more the sweatshirt than the formal type. And after she became a worldly wise chorus girl, the boys her own age skittered away, awed by her glamour. She also thought she had a great crush on Ray Sinatra, Frank’s first cousin. “That didn’t raise my stock any with the fellows,” admits Sheree, “but was I popular with the girls!”

“Donna had a project at Hermosa Beach and I went along to help. I hid a bathing suit in my notebook—black with white scallops. I made it myself and I looked just like Daisy Mae of Dogpatch.”

The project was to wangle an introduction to a dreamboat Donna had spied on the beach. They chugged down and there he was, stepping out of a convertible. But Sheree was not impressed at first. “He looked too much like Jimmy,” she says, “and I was on a dark, Latin type kick by then.” But she coaxed a policeman to help them meet Donna’s guy.

“We met him,” says Sheree simply. “I married him.”

His name was Fred Bessire, a twenty-five-year-old draftsman who worked for his contractor father, and things got very interesting for Sheree and Fred practically at once. In fact, that same day he asked her—not Donna—for a date, but she declined, loyally. Soon after, Donna

gave up and Fred took Sheree out. “The third date I’d ever had in my life,” she says. “We went to the Coconut Grove and I ordered salisbury steak and asked for a steak knife—it’s just hamburger, you know.” At the table Fred popped out a box with his mother’s diamond ring in it. “It really laid a bomb with me,” Sheree confesses. “I didn’t know what was up until he asked me to marry him and then I said, ‘Do you know what you’re doing— because I sure don’t!’ ” She got so rattled that she told him her real age—fifteen instead of the seventeen she’d fibbed about at first. But Fred said that was okay—they’d elope and keep it secret and she could live home until she was eighteen.

It might have worked. But after the ride to Las Vegas and back that made Sheree Mrs. Frederick Bessire, the secret didn’t last long. They forgot about the legal papers, which soon dropped into the mailbox. Sheree’s mother saw those and nobody had to tell her they weren’t really legal. You can’t get married if you lie about your age—even in Nevada. They had to drive back up and do it all over—with parental consent—in the Methodist church with a minister.

But it wasn’t all moonlight and roses for Sheree after that. They lived at Fred’s folks’ and at Sheree’s but she kept right on dancing for her living with sometimes bits on the radio and extra work at the movie studios. Almost a year later Sheree felt a little queer and went to see a doctor. “You’re going to have a baby,” he announced, adding, “any day now.” This was a complete surprise to Sheree.

“I just didn’t believe it,” she says. “I didn’t think anyone as young as I was could have a baby.” She was practically shanghaied to the maternity home by her mother but remained unconvinced, refusing to take an anesthetic. But the doctor was right. Her daughter Dawn was a real and convincing baby. Five weeks later Sheree was dancing again. This time she had to. She had a child to support.

Her marriage broke up right after that, but because of various court hassles she had to get divorced two separate times. Only last September did Sheree’s final decree arrive, and by then Baby Dawn was almost five years old.

She got chorus girl jobs at $50 to $75 a week around Hollywood’s night spots. Sheree did whatever came up. She went to Texas to model at the Shamrock Hotel, down to Mexico to pose for a resort advertising booklet. She made commercial films at business conventions and some on the daring dance side. Just recently, these had to be shown in a Los Angeles court where a couple of characters were up for sending naughty films through the mails. The judge looked at seven of them and decided Sheree was sexy but still nice. “They really weren’t very good,” was his verdict, “but still not bad.” Sheree said, “Now I can go to my PTA.”

Of course art wasn’t Sheree North’s aim then. She was scraping to pay Dawn’s milk bill. Things looked rosy once when a choreographer pal, Lee Scott, worked some dances with her and took them to MGM. Sheree got a utility dancer’s contract because they needed a high kicker for Sally Forrest then. She worked in one picture called Excuse My Dust but she’s not so sure she stayed in it. At least she’s never had a look.

The best spot Sheree ever drew during those struggle days was at the Flamingo in Las Vegas. She had worked for Nils T. Granlund, both in his girlie lines and on his Tv show, to win watches, bathing suits or anything useful. One day he offered her a job with his show in Vegas, as a specialty dancer, also helping on the routines and costume design. Although that resort didn’t bring back pleasant memories to Sheree, she leaped at the $175 a week, board and room. She stayed for eight months, working up a nice little dodge on the side just for fun.

“I used to get in conversations with the Big Wheels around the tables,” admits Sheree, “and casually mention it would be a nice night for a swim. It gets pretty chilly in Vegas on winter nights and they always thought I was crazy. So they’d bet me twenty dollars I wouldn’t dive into the pool.” With a bathing suit handy under her formal Sheree took them right up, raced through the icy wind and splashed like Esther Williams. Of course, she knew something they didn’t seem to know. The pool was heated—it was really just like taking a warm bath!

Her salary, tips from lucky gamblers (one gave her $500 with a line of sentimental poetry thrown in) and a number of swimming pool bets piled up the first decent stake Sheree had ever had. She knew what she wanted to do with it—get out of this up-and-down life away from home. She had plans for the secretarial course when she took that job at Macayo. Even after Bob Alton found her there she went ahead with it for several weeks. What changed her mind?

“He was the first man who ever had real faith in me,” explains Sheree. “He’d been through pretty much the same thing as I had—a divorce and a kid left to raise. I just felt he understood, that I should trust him and do what he said.”

Even with that assurance there were times when Sheree’s trip to New York for Hazel Flagg looked like another expensive wild goose chase. She had to buy luggage and winter clothes. Her salary was only $34 a week during rehearsals and they went on for almost two months. She’d never been to New York before and there were moments when Sheree North wondered if she should have her respectable plans. She had the flu, and a mixture of wet snow and rain was slushing on the brick wall she saw from her cheap inside room. She was a few bucks from broke and 3000 miles from home and her baby girl. To make things perfect, it looked like her dance spot might have to be cut out of the show.

“That day,” she says, “as far as I was concerned show business was no business!”

But the flu, the rain and the part cleared up. In fact, Sheree’s part bloomed into a headline spot the minute she stepped on the stage and let go with her red hot burlesque of “Salome And The Seven Veils.” One critic wrote, “I must be getting childish in my old age—but I swear I saw Gilda Gray dance last night, only she calls herself Sheree North now.” Another announced, “An H-bomb seemed to hit the Mark Hellinger Theatre last night but it turned out to be only the North star.” Sheree’s name went up in lights and her shimmy-shaking picture out on posters—neither of which had ever happened to her before. She took bows at the nightclubs, played the benefits, made TV’S Toast Of The Town, got interviewed and photographed—just like a movie star. “Also,” recalls Sheree, “I got engaged in the columns to a lot of playboys and business tycoons I’d never met. When I was supposed to be out romancing I was really home in my room soaking my feet.” All this excitement took twenty-two pounds off her figure but it was worth it.

When Paramount bought Hazel Flagg for Dean and Jerry’s antics, nobody could imagine putting on the show without Sheree North. She threw herself so enthusiastically into that first movie break that she cracked an arch and had to go to the hospital. But Bing’s tv offer made the foot heal fast. The furor raised by her TV dance wasn’t such a surprise to Sheree. “I don’t know why it is,” she says innocently, “but I’ve always been very censorable.” The movie offers which followed still make Sheree shake her cotton top in wonder.

Since then it has been all work and little play for Sheree North. For the last two months she has been tested at Fox from morning till night for “everything except my metabolism rate,” grins Sheree, but that doesn’t seem necessary. Already she has sung, danced and acted through the rehearsal scripts of two musicals, Pink Tightsand There’s No Business Like Show Business. Prospects for the first are still dubious, for after a thorough inspection it’s plain that Sheree is not Marilyn Monroe at all. Actually, she isn’t intended to be. She isn’t anybody except herself, which seems to be plenty. There’ll be room for both Sheree and Marilyn if Mrs. DiMaggio should change her mind and come back to the stable, Both are super sexy blondes but there’s little other resemblance. Sheree is primarily a dancer and strictly a funny girl. As for any feud a-brewing, that’s silly. The girls have met but only to say hello, a huge thrill for Sheree as is meeting any Hollywood star. “I still get a stiff neck rubbering around,” she admits.

Sheree’s break happened so fast that she has been caught flatfooted glamour-wise. Until just the other day she was camping in a tiny cottage out in Sun Valley, a hamlet thirty-odd miles from Hollywood where rents are cheap. She rattled to and fro in a battered blue Plymouth convertible with holes in the top. She’s been to just three Hollywood parties, two of them business affairs. She had to sew her own costume for the third, Darryl Zanuck’s Return From Korea blowout for daughter Susan and Terry Moore. The only Hollywood escort Sheree has had so far is her agent, Henry Willson.

Some of this deficiency is rapidly being made up. Sheree has just moved to a new furnished house nearer the studio with a big backyard for Dawn and a nurse to look after her. Another thing Sheree did with her first pay check was to start an insurance policy for Dawn’s education. Because Dawn, whom her mom describes as “a pug-nosed Jack Cole dancer type with a rosebud mouth,” is still what Sheree’s really living for. “My ambition?” says Sheree. “That’s easy—to raise a healthy, emotionally secure daughter, and be the right kind of a parent.” She admits she’d like a little help someday. While Sheree hasn’t a beau to her name in Hollywood there’s a man in New York (she admits under pressure) whom she has her eye on. She won’t tell his name. “It might scare him away.”

He walked in one afternoon at a young couple’s apartment where Sheree was baby sitting because she felt lonesome for her own. “I liked the way he held the baby,” says Sheree. “I’d like him to hold mine that way.” But nothing’s really boiling seriously yet.

Sheree keeps fit by working out with weights in a gym, riding and swimming. She takes a terrific tan (because she’s really a brunette). She’s also a health food nut with a weakness for yogurt and raw liver, but drinks and smokes when she feels like it.

There was a time when she could stay awake all night and once did for three days and nights, but now that she’s an old lady of twenty-one she’s softened up some. Mostly this is because nightclubs give her the shakes, understandably. The only time she’s entertained so far in Hollywood was when she rounded up her broke chorus girl friends from the old days and bought them all the beef they could eat at Lowry’s Prime Rib. That was one way she celebrated her new seven-year contract at Fox. Next morning she celebrated it in another. She went with Dawn to church, as she does every Sunday, and gave special thanks. Dressed in a neat tailored suit and modest bonnet, you’d never have thought she was Sheree North, the hottest thing on wheels in Hollywood.

Sheree’s private life—when you examine it—is nothing to raise anyone’s blood pressure, as her dances invariably do. But that’s just the point. At an age when most girls are still dewy-eyed and dizzy, Sheree’s already wise to the ways of show business. As she said, she’s had it—the glitter and star dust—and now she wants a chance at some of the good things in life.

Sheree is not lost in the clouds about her luck. She knows how fickle show business can be. She’s glad she decided against that job at Hughes Aircraft, but she’s keeping her shorthand and typing in practice. And around her neck Sheree wears a tiny gold horseshoe that song-writer Ken Darby gave her.

“I think I’ll hang on to it for a while,” she says.

THE END

—BY KIRTLEY BASKETTE

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE JULY 1954

No Comments