Saint Or Sinner?—Gregory Peck

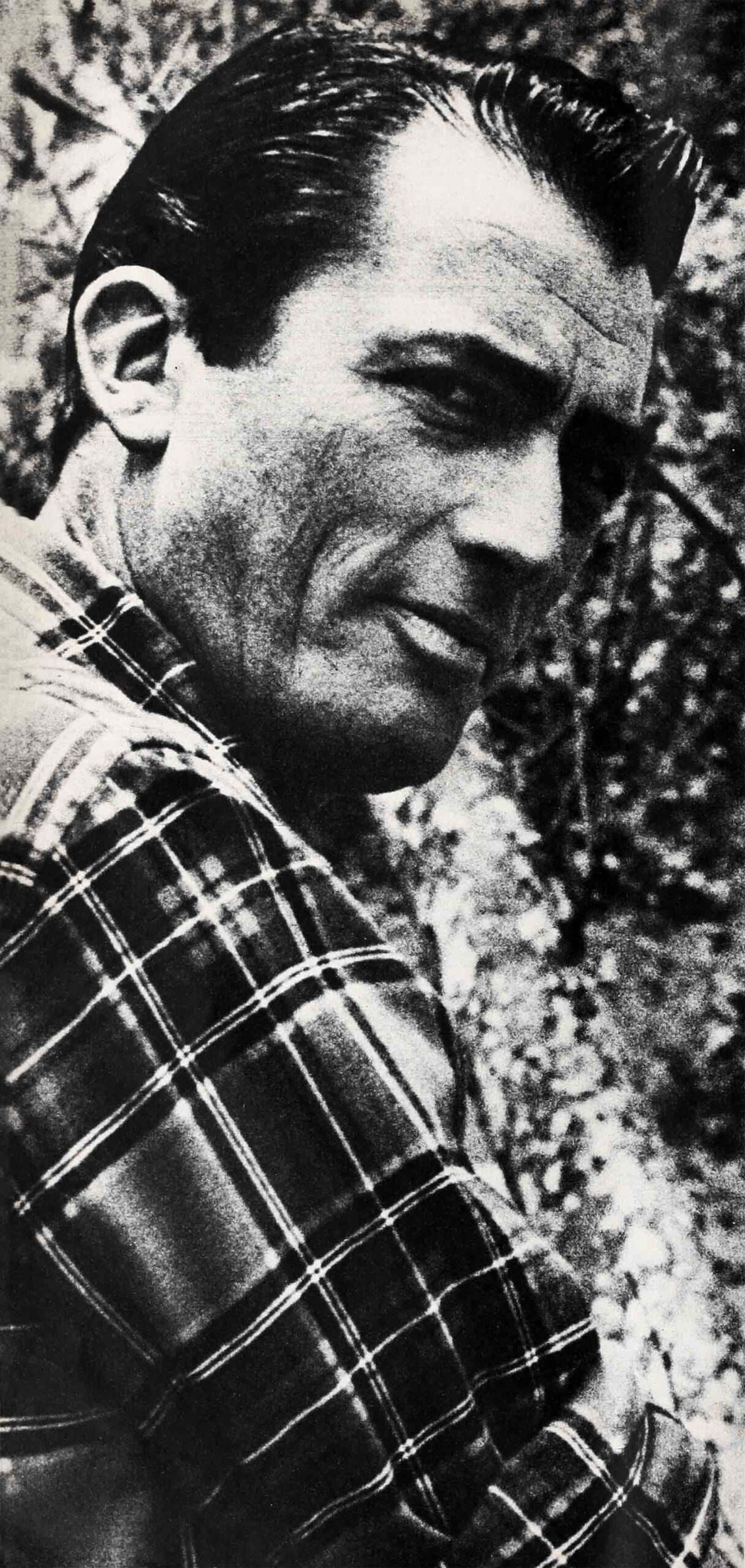

The first time Greg Peck ever wore a tuxedo, he rented it for a professional model job. Now he wears white tie and tails to be presented to royal families wherever they are still extant.

He was born in La Jolla, California, which doesn’t even have a census listing, but is absorbed in the population of the nearest big city, San Diego. Today, this small-town boy is a cosmopolite, who has traveled all over the world. He has become a gourmet and connoisseur of wines, speaks a smattering of French and Italian, has developed an appreciation of art and learned the difference between European and American women: (“In Europe a woman asks, ‘What can I give you?’ In America a woman asks, ‘What can I get from you?’ ”) But he abhors the International Set as much as he does Americans who become expatriates and delude themselves into believing they are now Europeans. (“These past three years in England, France, India, Germany, Spain, the Canary Islands have been a rewarding and enriching experience, but I am glad to be back inside USA again. Americans, no matter how welcome abroad, are still foreigners and, if they stay away too long. even the people who accept them as friends, frown upon them as expatriates.”) He also deplores the type of American who comes to Europe and complains when everything is not exactly as it was “back home”—from hamburgers to central heating—and who go to hotels and restaurants only for Americans, where they are laughed at for being suckers and disliked if they’re not.

Greg, on the other hand, wants to know the countries he visits, and he tries in the most expedient manner to get to know the people through their languages and way of life. In London, he had a flat in Grosvenor Square, presided over by an English housekeeper. In Paris, he traveled with a group of young French people. Last June, before starting his extensive six-month schedule in “Moby Dick,” he hibernated in a little village on the sea on the Basque coast, with only his stand-in for company. He wanted to share his holiday with this British actor who has been with him on every location trip, so he told him he needed him to help cue him with his lines.

Greg has no caste system in his choice of friends. He chooses them because he likes, admires and respects them—not because of their salary bracket, latest success or their name value on a guest list. He hates pretense of any kind. When he first came to Hollywood, he was put through the usual autobiographical routine; the studio publicity department was dismayed when he admitted out loud that his wife, Greta, had been Katharine Cornell’s hairdresser, and his uncle was a San Francisco streetcar conductor. It was subtly hinted that he should, for the sake of a more glamorous build-up, doctor the truth a bit. “But why?” was Greg’s retort. “They both made an honest living at their jobs, and they’re not ashamed of it, so why should I be? Besides, the truth will always out, so whom are we kidding?” he grinned.

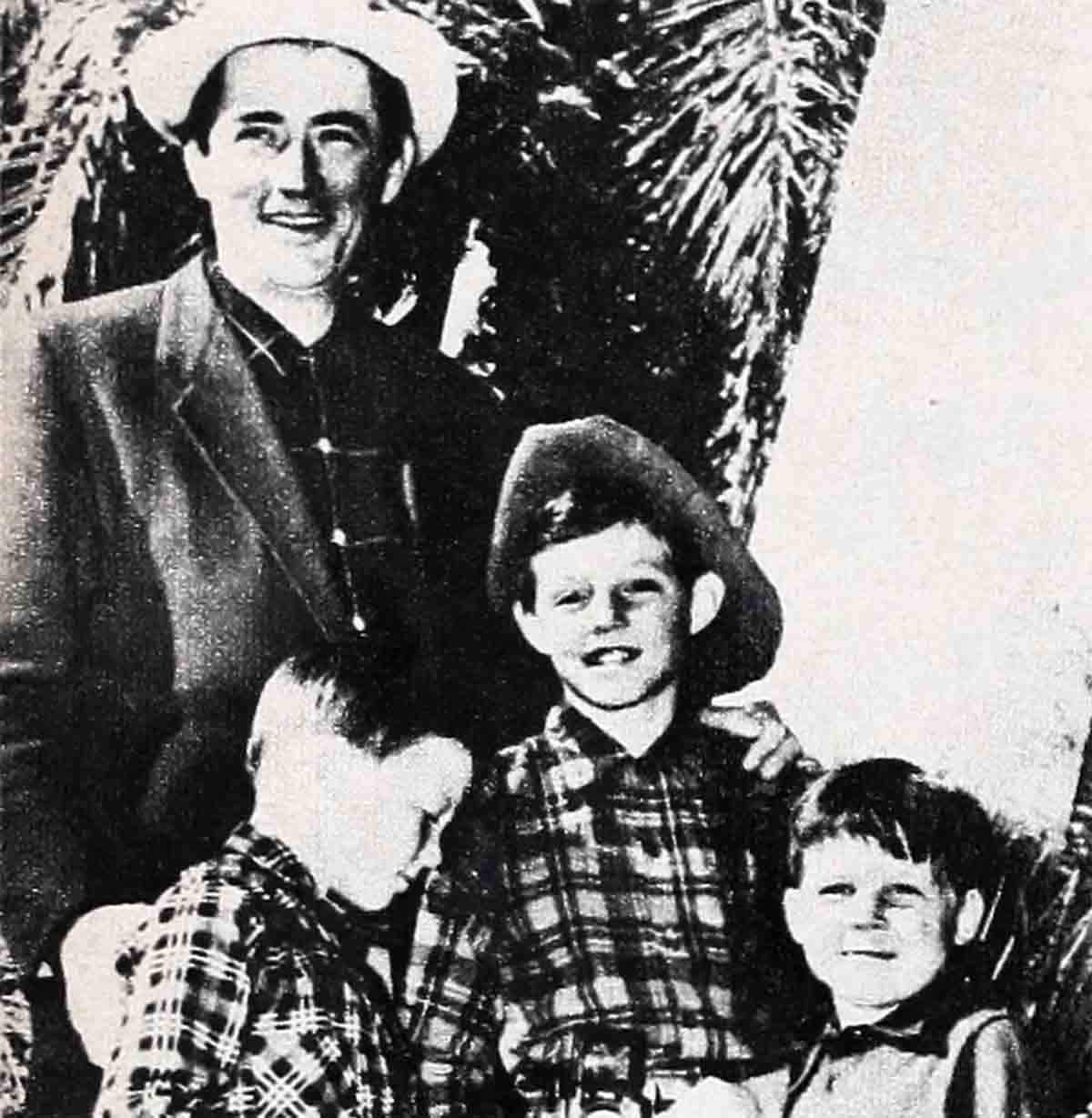

He is very shy about press interviews, only because he hates being asked questions unrelated to his career, particularly those prying into his married or romantic life. But get him talking on any one of his favorite subjects—producer John Huston, the La Jolla Playhouse, his specal recipe for a Pimm’s Cup, plays, a Goya painting in the Prado, director Willie Wyler, skiing in Switzerland, the Irish race horses he and Huston now own together, the cattle ranch where he hopes to retire in his “lean and slippered years” and his three proudest possessions, his three sons—and he’ll talk effortlessly and volubly. He has no interest in gossip columns or the sensational type of magazine that destroys reputations and tears the veil of illusion from the glamour that is synonymous with the stage and screen. But he doesn’t expect other people to conform to his standards. “Live and let live” is his motto. He has a personal press agent to cover his professional activities with dignified publicity and to sup-“press” such breath-taking bulletins as to whether he wears pajama tops, sleeps in a double bed and if his kisses with Audrey Hepburn in “Roman Holiday” were for real.

His recent divorce from the Finnish hairdresser he married thirteen years ago and who bore him three wonderful sons was not caused by a European femme fatale, as the Hollywood grapevine rumored it. It happened for the usual reason that so many Hollywood marriages like theirs break up. When Greta married Greg, he was a struggling young actor, playing a walk-on in Katharine Cornell’s company of “The Doctor’s Dilemma.” Three more plays followed, each of them short-lived, but Greg found himself in the unique position of being remembered for a series of flops. Hollywood inevitably beckoned, where the greatest thing that can happen to anyone overnight is recognition. With his Hollywood fame and new economic freedom, Greg and Greta’s lives changed. From an auto court, they moved into a hilltop home. Where their phone used to ring occasionally, it rang incessantly now. Greg, whose contract was divided among four studios, was at the beck and call of all four. His nonstop line-up of pictures and demanding schedule didn’t leave much time for home life. Even today, as one of the top stars in the business, Greg never lets down in his desire to give the best of himself to every role he undertakes. So you can imagine how he must have applied himself to exploring every facet of this new medium twelve years ago.

Before Greg married Greta, he had been too busy earning a living and too broke to sow any wild oats. Suddenly, he found himself surrounded by the most glamorous women in the world, who would have liked to continue their love scenes after the cameras stopped grinding. Greta, housewife and mother, sensed the competition every time she and Greg went out together. In Hollywood, wives of handsome screen heroes are looked upon as excess baggage—especially by other wives! But Greta also knew that Greg was not a playboy. He was essentially a home-loving man, who loved his wife and children. He also had too sane a sense of values to be flattered by the attentions of all the Hollywood Loreleis or the sycophants who breed on success. But sex, rearing its lovely head, isn’t the only thing that can break up a marriage. Unfortunately, Greta didn’t realize this. It was some wise philosopher who once said, “Not to go back is somewhat to advance.” Greg advanced. Greta didn’t keep his pace.

Greg’s advancement was in his contact with people who stimulated and excited his imagination. His Actors’ Theatre at La Jolla was another absorbing passion. He devoured his first trip to Europe like an overawed little boy let loose in a candy shop. As he developed as an actor, he grew as a person, emotionally and intellectually. Greta, through no fault of her own, didn’t grow in the same direction with him, so they grew apart. Greta was aware of the fact that she might be losing Greg, but not knowing why, she blamed it on other women. And then, she tolled her own death knell to her marriage when, in a huff, she packed herself and her three children and returned to Hollywood, leaving Greg alone in Europe for two years. It was a fatal mistake.

Greg still loved Greta as part of the life they had shared together for so long and because of the wonderful job she had done in raising their three sons. He didn’t want his marriage to break up, for all their sakes. But when he flew back to California last summer, just before leaving for location on “Moby Dick,” whatever was said between him and Greta on that visit, he returned to London with the knowledge that a divorce was inevitable. To Greta’s tremendous credit, she maintained a dignified silence all during the trying time of their separation when she was constantly being bombarded by the press for her version of the split-up.

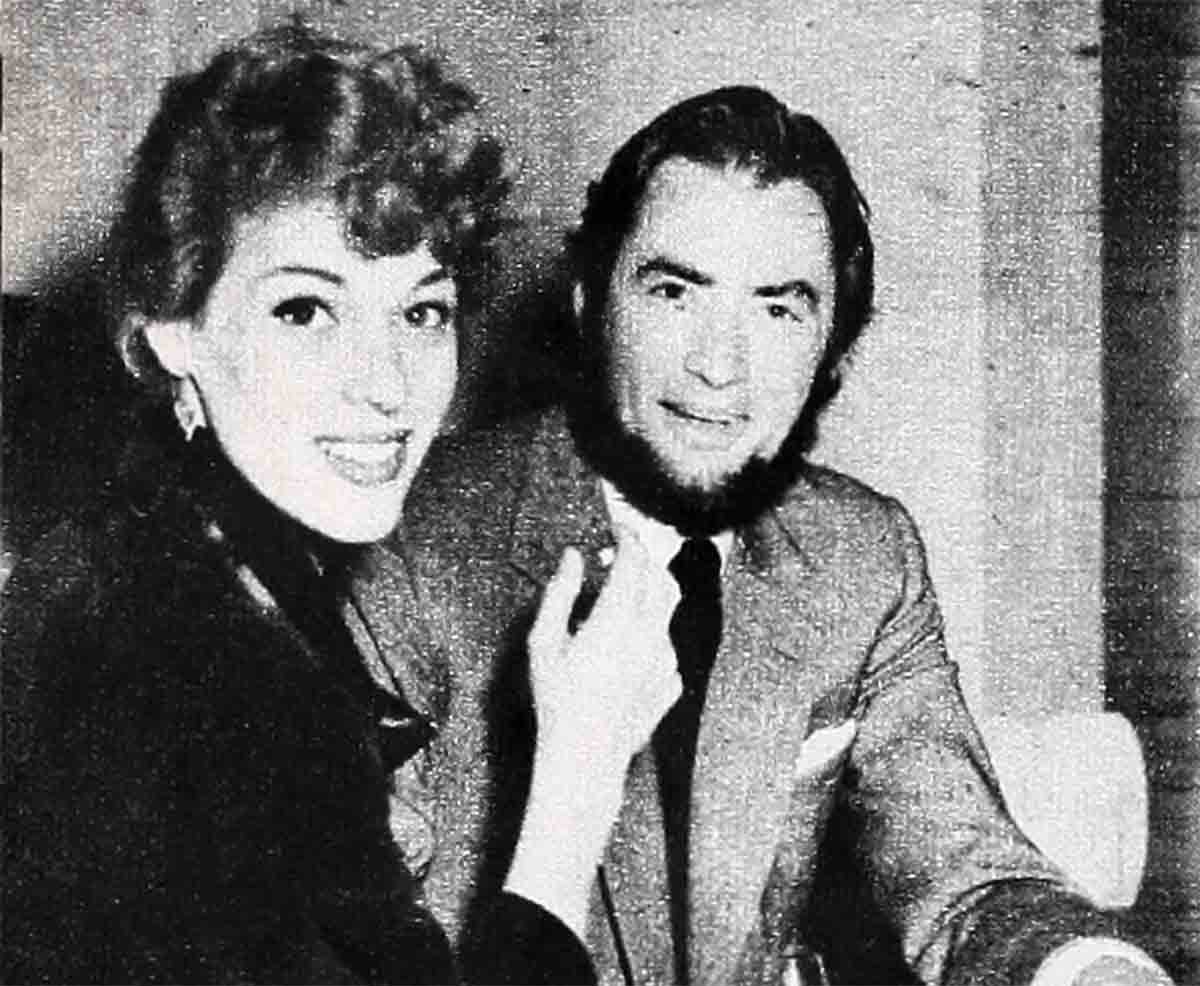

Greta filed suit in California on grounds of mental cruelty. She won custody of Jonathan, Stephen and Carey, with Greg allowed visiting privileges whenever he wanted to see them. She was also given their lovely house in Pacific Palisades and a settlement for herself and the boys. Greg is now living in bachelor diggings in a small rented home not too far away, but come December when his divorce becomes final, it is generally assumed that he will marry Veronique Passani, his constant companion for the past year. Like the plot of a Hollywood movie, Mile. Passani, a reporter on Le Soir, was assigned to interview him. It was Paris in the spring—the perfect setting for l’amour.

Greg brought Veronique to have cocktails with me when she arrived here on her first visit a few months ago. When I expressed amazement at her fluent English, she told me that she was educated at Marymount in Neuilly. She also explained the lack of her expected French accent. She isn’t French. Her mother is Russian; her father, Italian. “Veronique had nothing whatsoever to do with the breakup of my marriage,” Greg told me, with quiet firmness. “Nor could our romance ever be termed a public escapade.” Greg didn’t have to convince me of this fact. I knew how he hated the glare of the spotlight on his personal life. I also knew that he would never do anything to offend the dignity of his ex-wife or future bride.

It was quite obvious, seeing Greg and Veronique together, that, besides the chemical spark that ignited their romance, Veronique has given Greg the warm rapport of mutual interests he needed. Veronique, being European, hasn’t the American woman’s desire to compete with her man. She is perfectly content for him to be her lord and master. She is also smart enough to realize that she will have to share Greg’s love with eleven-year-old Jonathan, almost-nine Stephen and six-year-old Carey. Having been separated from them these past two years (although Jonathan flew to Paris alone and joined him in Switzerland for a skiing holiday), Greg now wants to be with them as much as possible. His one concern is that they not feel they are victims of a broken home. He is a doting father, but not the usual indulgent one like most self-made men who want their children to have everything they missed as youngsters. On one of his New York visits, I went on a shopping expedition with Greg to buy gifts for the boys. There was no extravagant ransacking of FAO Schwartz’s toy department. He knew what they would like, so he gave his order.

Carey used to go to a private school in Beverly Hills, but Greg ended that when one day he brought home his report card. Among his marks was a “C” for Hopping. “What does ‘C’ for Hopping mean?” Greg asked in puzzlement. “It means I hop on the wrong foot!” was Carey’s solemn answer. Greg was equally solemn when he said, “When the time comes that my son has to go to a private school to learn how to hop, it’s time he went to a public school!” And he does.

Greg lives by his own standards of right and wrong. He’s a right guy, all the way through, because there isn’t a phony characteristic in his whole make-up. He doesn’t surround himself with a coterie of yes men, buffers and hangers-on. If you call him, you don’t have to wade through a whole staff before you reach him. He always picks up the receiver himself to home calls. And if he says, “I’ll call you tomorrow at ten,” you can be sure he will. He doesn’t assume the kind of false modesty of so many stars, who insist they hate being recognized in public but always go to the places where they are sure to be seen. Nor does he wear dark glasses to church, because, as Fred Allen says, he’s afraid “God may ask for his autograph!” In New York, he usually avoids the popular haunts like “21,” El Morocco, The Colony and Sardi’s. “Let’s go to Manny Wolf’s and have a good steak,” he suggested on our last luncheon date. His is a genuine modesty and a sincere desire to close the door on himself as an actor when he leaves the studio and open it to a self-effacing fellow, who squirms uncomfortably in a goldfish-bow! Existence.

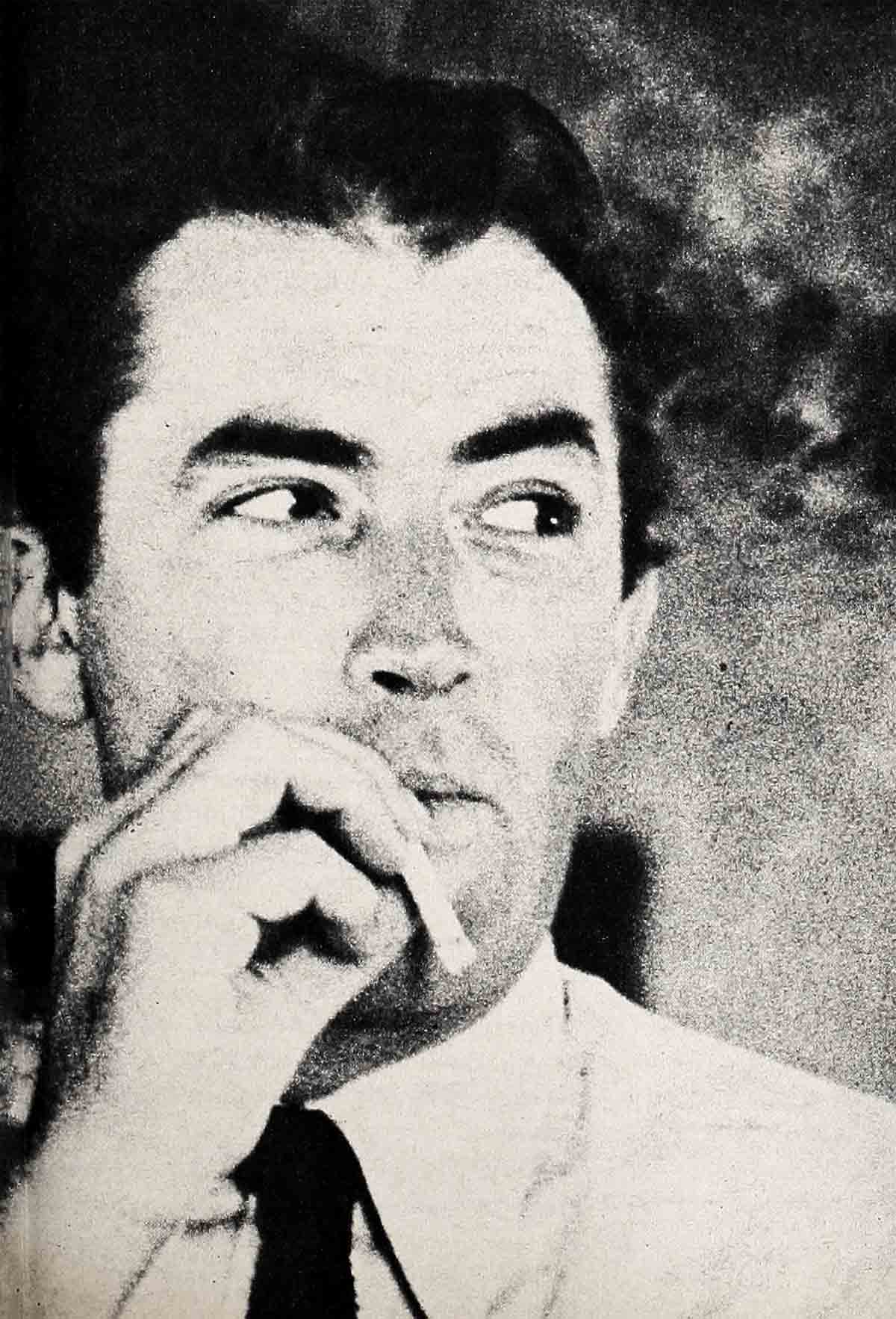

As Captain Ahab, the scarred commander of the whaling ship “Pequod,” Greg has robbed himself of every vestige of a glamour boy. Besides his whalebone leg, his handsome face is disfigured by a deep, livid scar and a wild, spray-soaked beard. During my visit in Youghal, I watched him in the make-up department, where he insisted there was to be no concession to the usual movie standards of realism. He went through several exhaustive, painful tests before he was satisfied that he was the Captain Ahab familiar to every reader of this Herman Melville classic.

In playing the role for six continuing, grueling months on location in Ireland, Wales and the Canary Islands (in addition to interiors at the Associated British Studios in Elstree), Greg didn’t spare himself either. With most of the action aboard the “Pequod” or in open boats, or astride Moby Dick in a rough sea, he never once used a stunt-man. When he was congratulated for his courage beyond the call of duty, his modest answer was, “Stunt-men are married and have families, too. And they don’t earn my salary!”

To director John Huston, Greg is cut from the same mold as his beloved father, Walter. “He’s the most patient, cooperative, understanding, kindest guy I’ve ever directed,” John told me. “A great human being—and a great actor. Everything he put into ‘Moby Dick’ shows up there on the screen. It’s a performance that will live forever.”

Of course, Greg is equally as enthusiastic about Huston and “Moby Dick” is his favorite of the twenty-two pictures he’s made since 1943. Runners-up are “Twelve O’Clock High,” “Night People” and “Roman Holiday.”

Although he now commands one of the top salaries in Hollywood, Greg is a long way from being “A Man with a Million” (an English picture he did, incidentally, and did not like). “Roman Holiday,” made on a percentage basis, has been a big money-maker, but since Greg didn’t collect his share until this year, half of it belongs to Greta, according to California community property laws. Uncle Sam gets a sizable hunk, too. Add to this another subtraction for Greta’s divorce settlement, the support of three growing boys, the maintenance of two homes, large commissions to his agents and all the other expenses of a top-ranking movie star, and there’s not too much in the bank account.

Greg’s next picture will be in Hollywood, but at this writing he is still poring over scripts trying to find the right one. It isn’t easy, especially since “Moby Dick” makes every other script suffer by com- parison. Jerry Wald would have liked him to play Eddy Duchin in the screen biography of a pianist he never knew. (“When Duchin was playing at the Casino-in-the-Park and at the Plaza I couldn’t have afforded a cup of coffee in those class joints!” confessed Greg.) There’s much more chance he’ll check back to 20th to be a war hero again for Darryl Zanuck. In the meantime, Greg is still anticipating the day when he will return to his first love—the theatre. His great friend, Raymond Massey, suggested a revival of “Abe Lincoln in Illinois” as a perfect vehicle for him, but Greg, with characteristic modesty, told Ray, “With the memory of your magnificent performance, no one can ever shine in your reflected glory.”

There is a revival, however, that he would like to do—Elmer Rice’s “Counsellor-at-Law.” “Paul Muni played it in the original production, back in ’31, but it isn’t a part that is identified with him in the same way that Lincoln is with Massey. It’s dated here and there, of course, but after twenty-four years, it still holds up as a strong drama. If, and when, I do this play, or any play, I promise you one thing. I’ll just it without a lot of premature announcements. I want the show to be the main event—not a ballyhooed trailer!”

Greg has another ambition in the not-too-distant future—and that is, to make a film in Spain. He visited Madrid for the first time on his way back from the Canary. Islands, and fell in love with it. He wants to go back and spend at least a week in the Prado museum. Greg, be it said, is the actor who knows that Rubens is an artist, not a New York restaurant!

But now, after three years, the traveler has returned home, and he is content to bury his roots in Hollywood for a while. Because, make no mistake about it, Hollywood is where his first loyalty lies.

The only time I’ve ever seen Greg really angry was defending Hollywood against a venomous attack by someone who had never been there. The incident took place in London, when Greg and I were both over there for the Coronation. We were dining together at the Caprice, when a note was sent over inviting Greg and myself to stop by the writer’s flat for a nightcap after dinner. Greg recognized the name of the sender as the wife of an Englishman, and although he had never met her, he remembered her husband and liked him. We were both exhausted by all the Coronation activities and didn’t particularly want another late evening, but Greg, with his never-failing courtesy, didn’t want to offend “Mrs. X,” so we went. There was another guest present—a young, untidy-looking man, who made no pretense of his obvious resentment against a handsome, successful American movie star. He immediately launched into an unprovoked diatribe against Hollywood, joined in by our hostess. Ordinarily, Greg, because he was in a complete stranger’s home, accepting her alleged hospitality, might have changed the subject. But this blast against Hollywood was like raising a red flag in front of a bull. This was the town that had given him his place in the sun. He was part of an industry he both respected and loved. Great creative artists have been nurtured by that industry. Their footprints aren’t left only in Grauman’s Chinese but in the pages of history. Most of them are hard-working, self-made, warmhearted and generous.

Greg made all these points, but he never lost his temper as he quietly but fiercely defended Hollywood from these self-appointed, bigoted accusers. When he’d had his say, we left. In the lift down, Greg turned to me and asked in amazement, “Imagine inviting anyone to your home just to insult him!”

Just having Greg Peck in your home is a privilege for anyone, here or abroad—not because he’s a handsome movie star, but because all 6 feet 2½ inches of him is every inch a gentleman!

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE SEPTEMBER 1955