Escape To Happiness

PART III

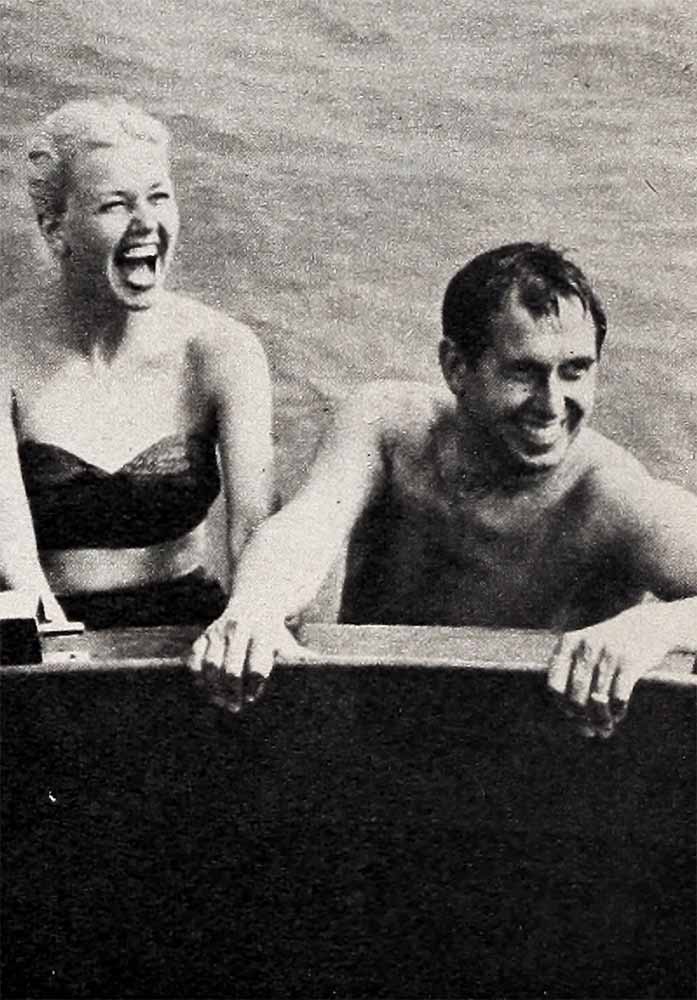

DORIS DAY’S COMPLETE LIFE STORY LAST INSTALLMENT

WHAT HAS GONE BEFORE: From the time she broke her leg to the time her second marriage ended, Doris Day lived in alternating happiness and despair, triumph and defeat.

Doris Day was numb after the emotional turmoil of her second marital breakup on the April day in 1947 when her agent, Al Levy, took her over to see producer Michael Curtiz about what might be her first movie role. Curtiz was planning to produce and direct a musical called “Romance on the High Seas.”

“Sing for me,” Curtiz directed in his strong Middle European accent.

Obediently Doris launched into “That Old Black Magic.” And burst into tears at the second line. In desperation she ’started the loud and raucous number called “Murder, He Says.” It was dismal.

“And what’s more,” she wailed, paying no attention to Levy’s alarmed shushing, “I can’t act either. I’ve never acted in my life.”

Fortunately, this honesty impressed Curtiz favorably rather than otherwise. He signed her for the picture and to a personal contract as well. At the end of one of the most unlikely auditions in Hollywood history a girl headed for stardom walked out of the producer’s office clinging to the arm of her agent and weeping.

AUDIO BOOK

Curtiz was not out of his mind. He knew Doris could sing. Everyone in the entertainment world knew that. What he signed up was that rarest of combinations—naturalness and honesty. As for acting, he would handle that one scene at a time, and do his best to keep acting out of it. He wanted Doris Day as she was, not as she would be in heavy makeup and with studied mannerisms.

Then began for Doris a bewildering period that she has since referred to as “Doris Day’s daze.” Her leading man was Jack Car son, the gay but innocuous story involved an assortment of romantic shennanigans on a boat trip to South America, and everywhere that she turned there were dancing girls, musicians, lights, cameras and Michael Curtiz.

She made mistakes. Her biggest mistake, and one that took her years to overcome, was that she could never remember to act like a star. On her solo numbers she had no difficulty in dominating the mike and the camera, just as she had dominated the audience as a night-club and radio singer, but when it came to asserting her starring role in a group scene she was always deferring to other actors. They might have lesser, or even insignificant, parts, but if they were experienced, with “names ” especially if they were actors whom she remembered from her movie-going days in Cincinnati, she was more apt to gaze at them in wide-eyed wonder than bounce her scene off them and take the camera for her own.

Curtiz, who has been known to get excited, was the epitome of patience with Doris. When retakes were in order, he blamed himself, the cameraman and stagehands, or some vague airplane that had put a buzz in the sound track. He never blamed Doris. And Doris responded by working so hard that Curtiz was moved to remark, “Such application! No complaints. Always cheerful. With her around, the whole set is happy and hard-working.”

Every director who has worked with her has said much the same thing since, but Doris had a special reason for working hard on her first picture, and making good was only part of it. Actually, she did not think she was making good, nor did she see any point in raising false hopes that she would ever make a second picture. Every day that she went to the set she was surprised to find herself still a member of the cast. She was hard-working because only by losing herself in her role, by driving herself to exhaustion, could she return to her lonely hotel room—living in their trailer home had become unthinkable after husband George Weidler’s departure—and find any peace in sleep.

The girl who appeared in the finished production of “Romance on the High Seas,” was a gay, vivacious blonde without a care in her happy, slightly-addled head. And that was the girl the movie reviewers and Hollywood writers believed she was. But that was not the girl who dragged herself home alone each night. At twenty-three Doris saw herself as a mother who rarely saw her child, as a wife who had miserably failed not once but twice in holding her husbands. Work was not merely the road to success, but an antidote to misery.

The sensitive Curtiz felt some of this conflict that was seething within his star. From the start he discouraged her seeing any of the rushes on her day’s shooting. once she expressed doubt about a scene, and asked to see how it turned out. “I liked it,” he said firmly, “and that’s good enough for you.” He was afraid that if Doris saw the frivolous blonde on the screen, she would try to redeem her in the next take by making her a solid, serious-minded citizen.

Thus began an odd policy that Doris has continued to this day. She will not see her rushes, and only when forced to attend the premiere of one of her pictures will she endure the agony of seeing herself as others see her. Today she has a good reason. It is in conflict with the accepted theory that an actor should study himself on the screen to better improve himself for his next roles, but it works for her.

She explains it this way: “When I study a script I develop a mental picture of the woman I am playing. I study that woman. By the time we are ready to start filming, that woman is very real to me, and I know just what she will do.”

“You actually become that woman?”

“To the best of my ability, yes.” She crinkled her brows, hunting for words. “Mind you, the woman I am playing isn’t like me at all. She’s what I think she is. Now, suppose I see the rushes of a day’s shooting. Sitting in the projection room, I’m not that woman, I’m me again. I look at that woman up there on the screen, and I don’t like her. Like in ‘The Man Who Knew Too Much,’ for instance. In some of the terror scenes I looked just awful. My mouth was crooked, my hair was all mussed, my eyes were swollen, my dress was like a sack. If I had seen the rushes of that—well, I’ll tell you one thing. I’d have marched in to Hitchcock and told him he was ruining me.”

“But I thought you did a marvelous job.”

“That woman did, not me,” Doris said emphatically. “In that situation, she was supposed to look awful, and as long as I was her, I knew it. Tears, moans, ugly mouth, everything. But me, personally, I don’t like to see myself looking like that. As I say, if I had seen the rushes, the next time we played such a scene I’d have settled my dress, combed my hair and kept my mouth straight. Consciously or subconsciously, I’d be trying to make me, Doris Day, look pretty instead of making that woman look real. So I don’t look at the rushes. As long as it’s a picture about that woman, I keep myself out of it.”

But Doris did not encounter this dual-personality conflict in her first pictures. “Romance on the High Seas,” with Jack Carson carrying the laughs in his inimitable style, was just light enough and fast enough to carry Doris to success without putting too much strain on her limited acting ability. At once Warner Brothers starred her in another picture, and then another, warning her meantime to avoid acting lessons like the plague.

“You’re a natural without lessons,” she was told. “They can’t improve you, but they might give you some wrong ideas. Just leave good enough alone.”

The odd thing about it is that, unsuspected by herself or anyone else, she was doing a superb acting job all the time. She was type-cast as the wholesome, bouncy, all-American girl-next-door, and no one was less that girl than Doris Day.

At ten she had started her professional dancing lessons. At an age when most giriş are giggling over their first dates, she was in bed with a shattered leg, her dancing career over. When other girls were going to the high school prom, she was singing for college proms with Bob Crosby’s orchestra. When they were off to college, she was on the road with Les Brown’s band, and when they were beginning their first serious romances, she was already a divorced wife and mother. And where other girls saw their own lives filled with humdrum reality and envied Doris her gay and romantic life in big-time show business, she saw the harsh reality of her world and envied them their special teen-age life filled with a sparkling magic of its own. She did not play the girl next door. She acted out her dream of that girl, and it was her glowing, envy-touched dream that added the extra lift to her films.

If her first films were repetitious they had their rewards. With her first paycheck she was able to bring her mother and Terry out to California, and for the first time in years she was with her son. One of the big moments in her life was when she moved with her family into a small, to her enchanted, cottage in Hidden Valley.

Movie fame also brought her big radio assignments, among them the Bob Hope show, and big recording contracts. Within two years of her first movie assignment, Doris was earning $500,000 a year in movies, radio and in recording royalties. In 1948 she recorded “It’s Magic,” still one of her favorite songs, and watched it soar over the million mark in a matter of weeks. “It’s Magic” seemed to be the theme song of her career, but it had anything but a magic influence on her private life, unfortunately.

Having twice failed in marriage, she became convinced that love was not for her. More and more she spent every free moment at Hidden Valley, shunning society with the fanaticism of a recluse. once, on a tour of Army camps and hospitals with Bob Hope, the plane bringing them to a landing in Pittsburgh so narrowly missed a collision that even Hope turned green. As their plane zoomed skyward, shooting over the other plane by inches, Doris decided that if she ever got safely back to earth, her days of constant travel would be over. Today she will travel only if Marty and Terry can be with her, and even then, as on her trip to Marakesh, Paris, and London with “The Man Who Knew Too Much,” she is uneasy until she gets back home. “Marty and Terry are the tourists in the family,” she admits. “They love to haggle in weird Arab bazaars, or find strange shops in Paris or London, but me, if I can’t find what I want on Wilshire Boulevard, I don’t need it. I guess I got in too much traveling while I was still too young.”

Another by-product of her young days that matches her unwillingness to travel is her reluctance to appear in public as an entertainer. Where once she would sing into the small hours seven nights a week for twenty-five dollars, she now flatly refuses $25,000 a week to make a couple of nightly appearances at some lavish Las Vegas casino. Except in the cause of charity, she limits her work to recording sessions and movie assignments where her audience is made up exclusively of professionals.

This reluctance can be traced back to “Young Man with a Horn,” in which she co-starred with Kirk Douglas. It was a strong dramatic part. Here the studio felt safe, because Doris knew all about music, about jazz and jam sessions, about one-night stands and about young men who played horns, having been married to two of them. But it was her toughest assignment. The movie sets of night clubs and theatres were too real. The situations and dialogue were too real. They carried too many overwhelmingly painful memories. Every day Doris had to force herself to belt out a few songs she had once sung for kicks, and what the director thought was a girl coasting through a natural role was really a girl in torment. Her withdrawal from public entertainment dates from that time.

Out of the eighteen pictures Doris made for Warner Brothers, only one other revealed her true dramatic ability, but this time with happier results. That was “Storm Warning,” in which she made her first venture into terror. As things turned out, it was a good break. If the studio had any doubts about Doris Day as a dramatic actress, it felt comfortably covered by having Ginger Rogers, a proven actress whose name alone could sell the picture, play the main lead while Doris supported her in the secondary role of her sister.

A few days after its premiere Doris was dragged, almost forcibly, out of her seclusion at Hidden Valley to attend a party of the kind that makes Hollywood glamourous to all but Doris Day. “You have to come,” she was informed. “There’ll be some people there you simply have to meet.”

Doris dutifully went to the party, was caught up by the social whirl and passed unobtrusively from one group to the next. In time, and to her immense relief, she found herself in a quiet corner where she could see without being seen. She began to relax a little. A few more minutes went by before she was aware of a silent bulk besides her that was not, as she had previously thought, a protrusion of the woodwork. With an inward gasp she realized it was Alfred Hitchcock, a man so notoriously shy that he has been known to pass up his favorite exercise of eating rather than make a public appearance in a studio commissary.

But if Mr. Hitchcock is shy, he is also the murder-master of Hollywood, whose film excursions into the more sinister aspects of crime have made him a connoisseur of sophisticated dialogue, dramatic acting and exotic sets. His first apprehension at finding Doris Day beside him dwindled as the minutes went by and she made no overtures to speak. It dawned on him that he was in the presence of a person even more shy than he, an emboldening experience. It even encouraged him to speak.

“You are Doris Day, are you not?” he asked in his meticulous Oxford English.

She yielded a frightened smile and a nod of assent.

“You can act,” he said accusingly.

A startled expression crossed her face. No one had ever accused Doris of that before.

“I saw you in ‘Storm Warning.’ Quite good, quite good indeed. I could use you in one of my pictures.”

Having talked himself out in some thirty words, and being quite flustered as a result, Mr. Hitchcock bounced himself off to a more neutral corner. To this day Doris does not know if she got out more than a blurted, “Thank you.”

But the die was cast. Doris took the words home with her and treasured them, and began to think about them. Could she really act? Or would she always be the girl next door until some younger candidate came along and made her obsolete? It was time, she decided, to find out.

Other matters were coming to a head, as well. Down at her agency Al Levy had his hands full just watching out for her movie contracts. Young Marty Melcher was working long hours on her radio and recording contracts. For reasons never quite clear to him, Marty was also handling such of her non-musical enterprises as balky lawnmowers, faulty plumbing, blown light fuses and the weekend shopping. It was just a convenient arrangement. As he and Doris both knew, romance was for the birds, and they got along splendidly well on a platonic basis. What was more, he, too, thought Doris could act.

It was Terry who precipitated matters. Too young to be disillusioned about romance. and delighted at an occasional chance to have a man around the house, he suggested that Marty’s handyman status be made permanent. Suddenly struck by the wonderful fitness of the whole idea, Terry’s mother and her agent forgot all about platonic friendship. Love, too long held back by a bitter, we-know-better restraint, swept the two of them away like a flood.

“But it’s not true that we interrupted a shopping trip, and went to find a justice of the peace with our arms loaded with packages,” laughs Doris. “We weren’t in that big a rush. We waited until my birthday, April 3, 1951, and went to get married by Justice of the Peace Leonard Hammer. We wanted a quiet marriage so we didn’t tell anybody in advance, not even Mr. Hammer. When we got there he was tied up for another hour or so. We didn’t want to be conspicuous sitting around the hail, so we went shopping for some new draperies to kill time, that’s all.”

So careful were they to keep the marriage quiet that among other people they had failed to notify in advance was a witness. Needing one, Marty searched through the small town hail, closed for the noon hour, and returned with an obliging young man named Richard Turpin. The ceremony concluded, the happy young Melchers stole quietly away. They had accomplished the impossible—an unpublicized wedding of a major Hollywood star.

Except—as screaming headlines informed them a couple of hours later—that the obliging Mr. Turpin was a newspaper reporter, who knew a story when he witnessed one.

They had planned on no honeymoon, but with the press, radio, and television hard on their heels for interviews, they fled on what Mrs. Kappelhoff informed all callers was a long trip to the mountains, or the desert, or the beach, or someplace. A day or so later they slipped quietly back to Hidden Valley. A honeymoon involving travel and impersonal hotel rooms was not Doris’ idea of the happiest way to start her new married life. She wanted home.

With a man around the house, quarters became too cramped at Hidden Valley. At this point Martha Raye decided to give up Hollywood in favor of Broadway and the night-club circuit, and her house at Toluca Lake, convenient to Warner Brothers, was so exactly what Doris and Marty wanted that they snapped it up. “Now we’ve got a house big enough to entertain in,” they told each other happily.

But, once moved in, Doris did not want to entertain, nor did she want to go out to other parties. She just wanted to be with her family, with no interruptions. All her working life this girl had always been the paid entertainer, but never the hostess who entertained, and the thought terrified her. When social obligations practically forced her to throw a party, she stood out in the hall trembling, afraid to enter her own living room until Marty took her arm reassuringly.

Occasionally she would run into Hitchcock at one gathering or another, but either he was too busy with his current work, or he regretted his previous loquaciousness, because he made no second mention of her dramatic ability. For the time being, that was all right. Marriage had calmed some of her restlessness, and at Warner Brothers she was being given a chance to develop her talents in still another line. She, who had been a professional dancer at fourteen and been told she could never dance again, was now becoming a dancer. The crash that had shattered her leg had not destroyed her talent or her will. Uncertainly and on painful muscles at first, she danced with growing confidence. In “Lullaby of Broadway” she did some of the most difficult steps the art has to offer, including the trick of dancing up and down a long flight of stairs.

Doris Day was dancing again. She had a happy home-life. Her studio was happy with her talents and perfectly willing to pay her hundreds of dollars for making pictures that were fun to make. But to her, one question now became paramount.

“Can I act?”

She quit the studio. She quit to freelance, to wait for some producer—any producer—to give her a solid dramatic part. It is a rough decision for any actor to make. Rougher still for Doris, who had a million-dollar reputation as “the girl next door,” but little more than her own intuition to assure her she could act. As one critic remarked, with more flipness than charity, it was like quitting musical comedy to wait for an offer from grand opera.

Doris had plenty of offers. She was too valuable a property to remain ignored. But her would-be producers all wanted to star her in the same sure-fire roles that had helped keep Warner Brothers a prosperous concern. She turned them down, but a gnawing doubt began to creep in. Lonely years of breaking into Hollywood, in which hard work was her only antidote to misery, were now taking their toll. And she had worked harder than she or anyone else knew. Easy lines that an experienced actress could toss off with the lift of an eyebrow had been an ordeal for her, and the difficult lines that she had mastered were not so much the product of inspiration plus training as they were of sheer perseverance. To mental turmoil was soon added a health problem, memories of which are painful even today.

At this critical point she wanted comfort only from Marty, from Terry, and from her mother. Least of all did she want to be hunted up by the press and interviewed on love, marriage, success and the details of her private life. In return for this “lack of cooperation,” the Women’s Press Club of Hollywood voted her their Sour Apple of 1954 as a Symbol of their disapproval. Upon receipt of this news, Doris came close to collapse.

“It was the lowest period of our married life,” Marty admits frankly.

Then came the big offer from M-G-M to star with Jimmy Cagney in the highly dramatic “Love Me or Leave Me,” a turning point in her professional life. The picture was based on the life of Ruth Etting, a famous singing star of early radio and speakeasy days, who in private life was the unhappy victim of too many bouts with the bottle and with a husband whose tenderness seldom rose above a belt on the jaw.

Marty, who had given up his role as agent in favor of keeping business out of the family, was perfectly willing to let his wife find herself in a difficult role, but her friends were horrified.

“How can you play Ruth Etting?” she was asked countless times. “You don’t drink. You can’t stand brutality. And think of your fans. They know you as the wholesome girl in the high-necked gingham dress. How can you let them down in a picture that deals with sex and booze and even murder?”

But Doris went ahead. She turned in a performance so outstanding in its dramatic intensity that it won for her the International Laurel Awards Poll conducted by motion picture exhibitors. On the strength of tickets purchased at the box-office window, Doris Day was the top actress of the world, successful as never before.

Shortly before the end of shooting on “Love Me or Leave Me,” Doris ran into Alfred Hitchcock.

“Now,” he said.

“What?” asked Miss Day.

“‘The Man Who Knew Too Much.”’ “Good.”

It was one of the shortest negotiations in Hollywood history, but then, because of the length of the title, it was pretty long-winded for those two at that. Doris knew she wanted to work for Hitchcock, and Hitchcock knew he wanted Doris for the remake of his all-time favorite movie. Need they say more?

With the release of “The Man Who Knew Too Much,” Doris made permanent her right to be called a dramatic actress and a star of the first magnitude. Then came “Julie,” an independent venture by a new company called Arwin Productions, which happens to be Mr. and Mrs. Martin Melcher. Now she is busy with “The Pajama Game,” a vehicle for the full measure of her triple-threat talent, as a singer, as a dancer and as a dramatic actress.

But it is not in the flowering success of her current career, deeply satisfying though it is, that the real climax of Doris Day’s story comes. It is in her personal life, her fresh hold on the world, created by her years of struggle, of pain and joy.

In part that fresh look arose from her recent work. “When Marty and I were working as business partners on ‘Julie’,” Doris says, “it made us realize how important our family life is, and I think that is the most important realization that has ever come to me.”

But the climax is more than that, too.

Last summer Doris took a serious operation in her stride. Upon release from the hospital she asked her doctor, “Will I be able to play tennis?”

Thinking she was asking only if the operation would interfere with her tennis style, he answered, “Think nothing of it. You can play all the tennis you want.”

Whereupon Doris hired an instructor and put in an hour a day on the courts for the next week. When she reported her progress to her doctor, he was appalled. “I didn’t mean you could play tennis now,” he protested. “I meant after you had recovered from your operation.”

“Oh, that,” said Miss Day. “I recovered from that the day I left the hospital.”

That’s Doris Day on the health side. But more important, her “rest” in the hospital had given her time to think over certain other matters. As a result, she had decided that she was going to learn about baseball, and swimming, and tennis, and fishing, and all the other sports she never had time for when other kids were picking them up instinctively. She would recapture her youth while she was young enough to en joy it, and old enough to appreciate it.

That’s exactly what she’s doing, with enthusiastic support from Marty and Terry, who are enjoying their roles as sports instructors to the full. And Doris is having more fun than she ever dreamed possible.

All the confusion and all the indecision are gone. And what will happen in the future? Back once more to the drifting, aimless program of letting whatever will be, will be? No, it’s a delightful philosophy and makes a charming song, good for a fortune in records alone, but it’s no longer for Doris. She has found her career, her family and her home. Whatever will be had better be in the direction of making all three of them richer, more satisfying, more her own—or she will bat the charming philosophy right in the eye. And that goes for the fortune, too.

THE END

WATCH FOR: Doris Day in Warners’ “The Pajama Game.”

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JUNE 1957

AUDIO BOOK