Out Of The Shadows—Suzanne Ball

Fate wrote a bitter script for Suzan Ball.

It marked her early as a beauty, it let her grow into a striking young woman with a record of small and large successes. She won recognition in Hollywood, and then, unbelievably, though she was only eighteen she was struck down by cancer.

The excitement of her proximity to fame faded. The loneliness that loomed ahead overshadowed everything else in her life.

That was the script—but that isn’t the way Suzan Ball is playing it. Out of her courageous wisdom, and the new love that came to her, the will to rewrite fate was born. The new scenes are not filled with despair but with hope, not death and the dread of death, but life and the special joy of new life.

Suzan Ball was born in Buffalo, New York. She remembers running through the streets there when she was a child with such a surge of life that she once cried out aloud: “I’ll just never be sick. Not in my whole life I won’t! I won’t even get old. Not me!”

When her parents came to southern California she was delighted. She attended North Hollywood High, won fair study marks and with her dark-haired, hazel-eyed beauty won a new beau every two weeks. She discovered she had a good singing voice. After her graduation at seventeen her parents wanted to move again, this time to northern California, but Suzan refused to go with them. There was a family scene.

“I’ve got a future here!” she cried. “I know I have. I’ll succeed.” She hoped to get into musical comedy. Finally she won. She went to live in the House of Seven Garbos from which Ruth Roman and Linda Christian and others have gone on to success in motion pictures. Her family went off to northern California.

She sang with small orchestras . . . sometimes for as little as $15 a show. She took a job in a Beverly Hills cleaning shop, taking bundles in over the counter. And, incredibly, she got into pictures! The husband of a girl she knew was a writer. He arranged an interview for Suzan at Universal-International. They liked her, signed her and started her training.

Then in a dance routine in the studio, her foot slipped and her knee was hurt. Two months later, on a personal appearance tour in Boston, the same knee was hurt again in a minor automobile accident. Last April after a thorough examination, she heard the frightful diagnosis—not just the possibility of cancer, or the beginning of cancer, but cancer fullblown and raging through the bone of her right leg just above the knee. Her life was in danger unless the leg were amputated. The time for decision was short.

So much of the bone had been invaded by the tumor that if the malignant tissue were removed there would not be enough bone left to support her weight, she was told. Unless surgically removed the cancer would spread, leaving her, perhaps, only a few months more of life. This would be the risk she would take if she sought to treat the tumor with X ray: the chance of curing her leg would be slight, and the chance of fatal consequence unless she had surgery was considerable.

Suzan had to take it from there alone. Roughly her choice seemed to be to lose the leg and live, or to keep it and die. Besides pure horror, she experienced then her first entirely honest moments with herself.

“After eighteen years of self-concern,” she recalls, “the prospect I faced was so awesome as to seem impossible. Already, there was a dirge in the air. It came in the form of condolences. ‘Gee, Suzie, I’m sorry to hear about it. If there is anything I can do . . .’ they’d say, and then they would be gone. There was something frighteningly familiar about these phrases. And then it struck me. They all sounded just like I used to sound when I professed sympathy for someone and immediately forgot about him.

“It proved to me that I was worrying about what was actually a small indrawn life, this one I had led. It must have been so if I had not been able to muster up an honest sentiment for another person. Really, I asked myself, did my life amount to enough to be worth saving? Not until this question failed to shock me more than the fact that I had cancer shocked me, did I believe I was getting properly objective about my problem. You see, if I overrated Suzan Ball I might talk her out of taking a chance she perhaps should take.”

This little conference with herself took place last April when she had been at Universal-International Studios for a year and a half. Even though Universal had high hopes for Suzan and had starred her in several pictures, she felt that she still had a long way to go.

Now that she had taken a good square look at Suzan Ball, Suzan Ball decided she was not so important that she couldn’t take the risk of X-ray treatment. Her doctor’s plan was to control and eradicate the cancer by X ray and then restore missing bone structure by the process of calcification. It might take a year or more and Suzan would certainly have to wear crutches through all this period.

Having made up her mind to go ahead, Suzan also decided there would be no dramatics about it, no living with pent-up hysteria ready to burst forth if she found that she had guessed wrong and the malignancy became general. To be even more thorough in her self-reformation she did not permit herself to brood. Rather, she sought ways of keeping herself busy.

Instead of avoiding the studio and curious stares, she reported regularly. She began a course of study in English, Spanish and French. She even tried to talk writers into creating wheelchair parts that she would be able to play.

She talked to everyone and overcame her sensitivity about her misfortune. She didn’t, as she first thought she must, avoid running into Tony Curtis. His favorite greeting to everyone was always “Hi’ya, Gimpy!” and he would be sure to forget himself and say it to her. She was right. He did forget. But she was able to laugh it off, much to his relief, too. She was able to do more than that.

Her parents were divorced after they left North Hollywood. Her mother stayed in northern California with Suzan’s younger brother, and her father came to live with her. Suzan needed help now and she advertised for a maid, staying home one afternoon from the studio to talk to applicants. The bell rang and on her crutches Suzan went to open the door. A young girl stood in the hall. Seeing Suzan she involuntarily cried out, “Oh, you’re a cripple!” Then she looked terribly embarrassed. “I’m sorry. I didn’t mean to say that.”

Suzan felt the blow but she was delighted to find herself smiling and answering easily. “Yes, a cripple, but just temporarily, I hope,” she replied. They talked and the maid is with her to this day. She is a fine person and a mainstay at Suzan’s apartment.

Suzan achieved an air of self-sufficiency despite the fact that she had to depend on her crutches—an air that stood her in good stead when she began to feel that a tall, brown-haired fellow around the studio was taking more than a passing interest in her.

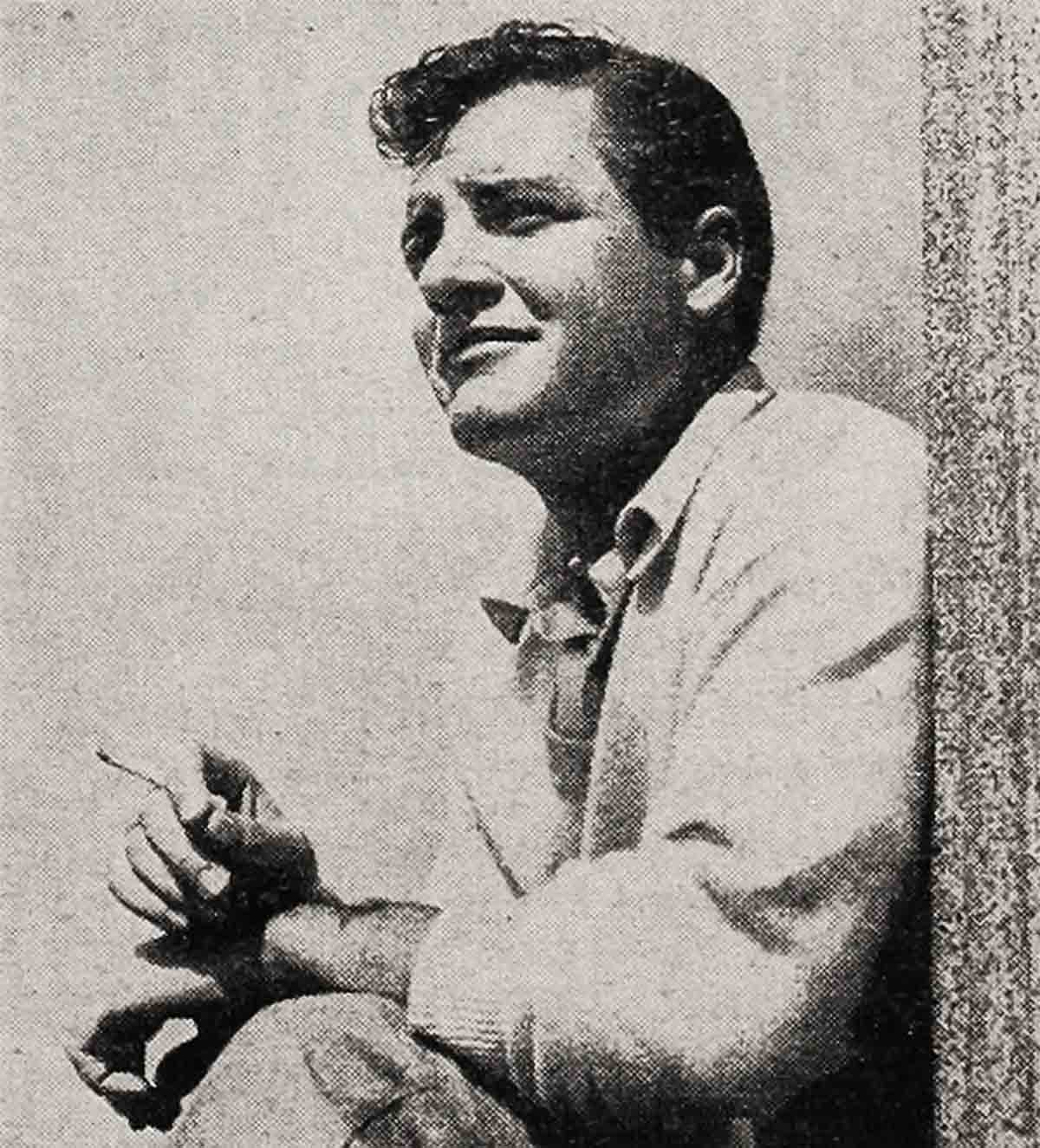

Richard Long had come to Universal as an actor before Suzan but had left in 1950 for two years in Korea and Japan with the Army. While he was in Tokyo he saw a picture called Yankee Buccaneer, made by his old studio. Suzan was in the cast. He made up his mind to meet her as soon as he got back to Universal.

When he resumed his career, playing a featured role in the Barbara Stanwyck-Richard Carlson co-starrer, All I Desire, he saw Suzan in the studio commissary, got an introduction and talked to her for a minute. The next time he saw her they talked for ten minutes, the time after that for an hour and the fourth time they lingered at their table for three hours after lunch was over. It was then that Dick found the courage to ask Suzan what was wrong with her leg.

Suzan remembers this as the first crucial test of her acquired policy of honesty—to others as well as to herself. She felt a temptation to soften her answer, to lead up to the truth by speaking about a treatment which gave every promise of curing something that might have been serious. She finally gave a one word answer: “Cancer.”

It shocked Dick all right. He’ll tell you that. “But also,” he recalls, “I felt an admiration I had never felt before for anyone I knew personally. I detected no self-pity in Suzan’s face nor heard a trace of it in the tone of her voice. I said to myself that when I saw her on the screen in Tokyo I considered her beautiful, merely beautiful, but now I had found dimensions to her character and nature that made her, well—inspiring!”

After a beginning like that neither of them was going to stoop to kid each other about anything, about themselves or their romance. When Dick worked in a scene and wanted honest criticism he knew just where to go for it. And he knew that was what Suzan wanted from him; her fling with pretense was over.

Handicapped as Suzan was, she was far from a restful influence on Dick’s life. “She has a dynamic nature,” he reports. “She is always on the go, impetuous, eager for every moment of life.” But Suzan’s impetuosity had its limitations, Dick learned, when he asked her to marry him last October. Before she could answer that one, she told him, she would have to do a lot of thinking. She didn’t have to tell him that her thoughts would include the question of survival. Was she going to be around for any length of time? Up to now there had been medical reports that bone calcification was proceeding satisfactorily but there was no assurance that cancer was gone. So Suzan kept saying no.

Late last November Suzan’s dog, a brown, miniature French poodle named Cezanne, brought on the hour of decision in Suzan’s life when he knocked over his drinking bowl on the kitchen floor. Suzan entered a few minutes later, slipped on the wet tile and broke the twice-injured leg in the very same place where the process of bone building had been going on for such a long time. She remembers being conscious just long enough to think of this with a great pang of regret. Luckily Dick was present in the livingroom and heard her fall. He picked her up, telephoned the doctor and Suzan was in the hospital before an hour had passed. There, after an examination made on the operation table, she got the finest news she had heard in a year. There was no trace of cancer. Surgery could now be used to graft bone from her hip to the leg and within a few months she could be back on her feet. Cezanne had in effect told his mistress, “If you’re going to be well, let’s take the shortcut.” There was another shortcut. Dick, who had been proposing on the average of every other Thursday, suddenly woke up to the fact that Suzan was saying yes.

“When?” he asked.

They went a little crazy and decided Suzan would be spirited out of the hospital somehow and flown to Las Vegas that very weekend for the marriage. But good sense prevailed. Instead, that weekend, just a fortnight before Christmas, the bone-grafting operation was performed. When Suzan came out of the ether, the doctor told her the surgery had been successful and there was nothing more to worry about. She remembered a quotation from Dickens’ Bleak House—“A person is never known till a person is proved,” and understood for the first time what it meant. She felt wonderfully strong and sure of herself, and certainly Dick had proved himself.

Then she and Dick made their plans, according to which they will have been married for weeks by now. She will be back at the studio, ready and able to work in a picture, and they plan an interesting future, perhaps eventually combining their careers on the stage. But whatever their professional success, or their lack of professional success, it is not to interfere with their personal lives.

Suzan and Dick want children. They want a baby of their own as soon as they can have one, and they plan to adopt one. They want their real life to go on with no interference from their efforts to interpret life on the screen or stage. They mean this even though they kid each other about it, and about the fact that with Suzan now able to hobble about they are everlastingly on the go.

“You see, like I said, Suzan is dynamic,” commented Dick. “She doesn’t want to miss a thing.”

“I’ve been marking time. Don’t you understand?” countered Suzan. “I’m well now.”

“Yeah,” said Dick, teasing her. “You had your chance and you had to get your leg well and pass it up.”

“Chance for what?” asked Suzan, puzzled.

“To be a second Sarah Bernhardt, of course. She did her best acting on crutches!” said Dick—and then ducked. Suzan had pretended she was going to throw Cezanne at him. Instead she threw herself into his arms.

That’s the way the script reads now . . . in the life of a girl who lived with death for months—to earn a chance to live with real happiness.

THE END

—BY ALICE HOFFMAN

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE MARCH 1954

No Comments