How Tony Curtis and Janet Leigh Saved Their Love?

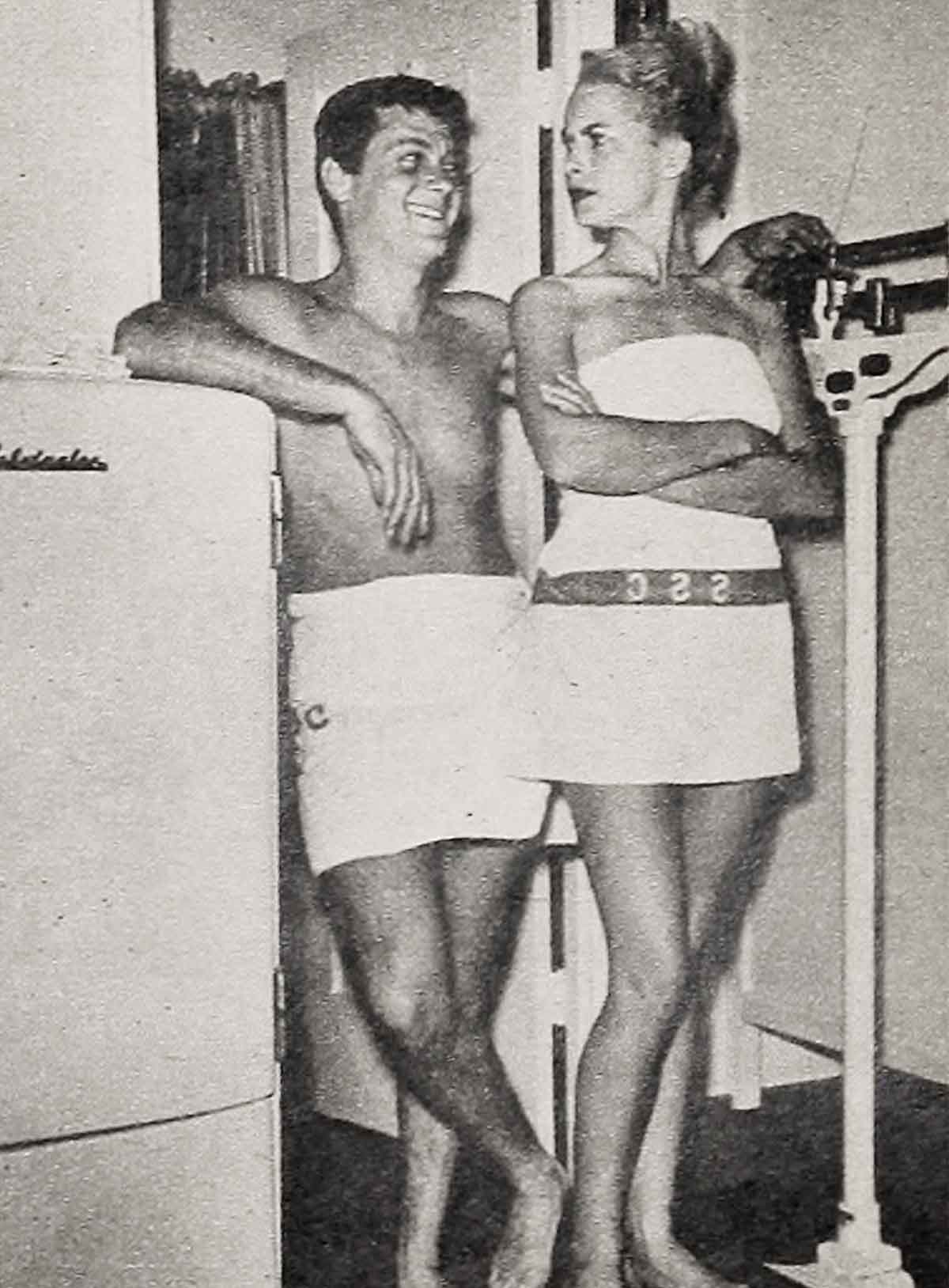

It was Janet who was supposed to be badly in need of a rest but it was Tony who kept dropping off into short naps after they got to Palm Springs.

“See? Him’s tired, too,” said Janet when she came out of their room at the Racquet Club in her new gold bathing suit and found Tony lying on his tummy with eyes closed at the edge of the pool.

“Cut out the baby talk,” said Tony, still with eyes shut. “I bet you put on the gold suit even though I told you I liked the blue job best. Why? Must a wife keep her husband guessing even after they have been married three years?”

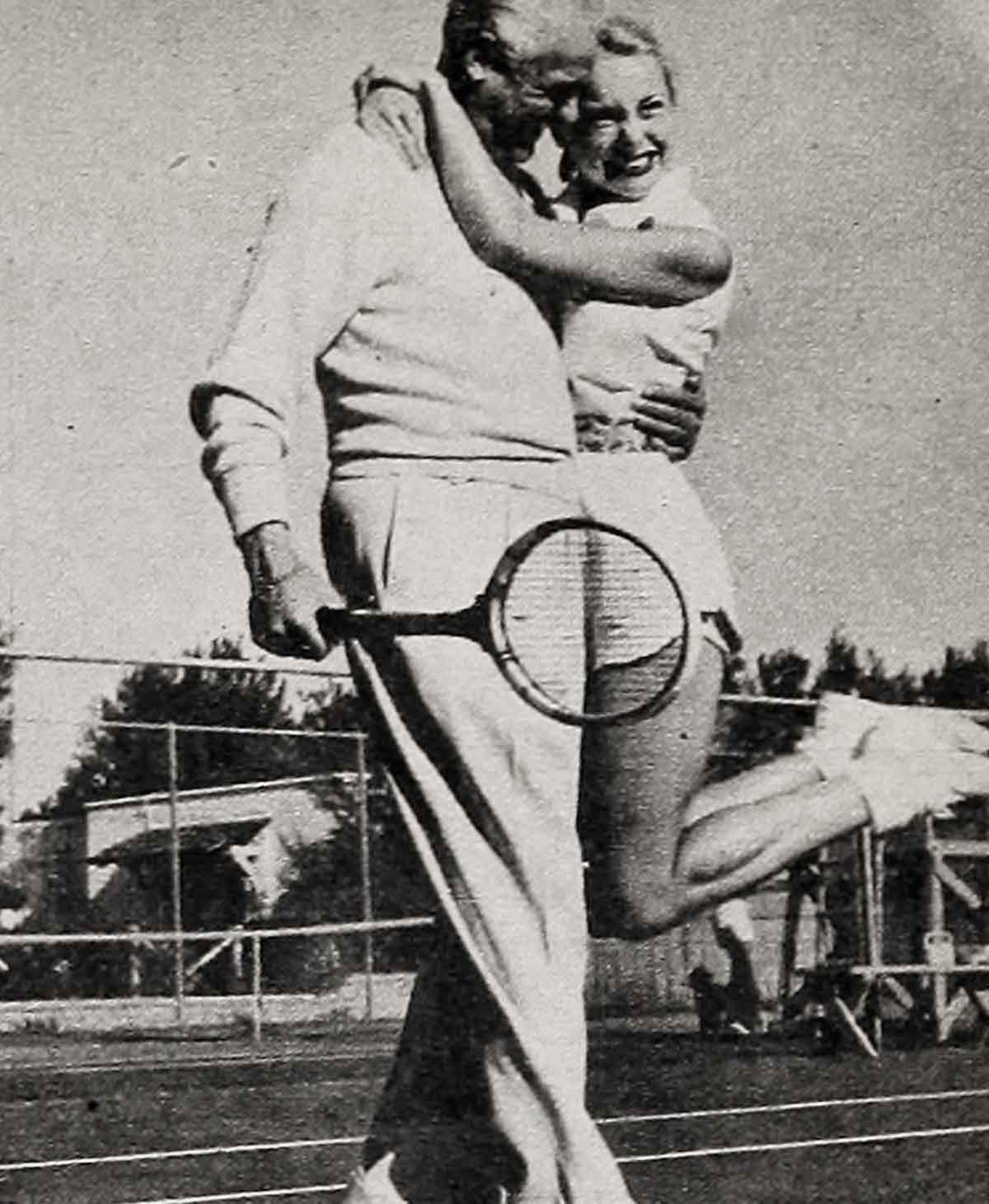

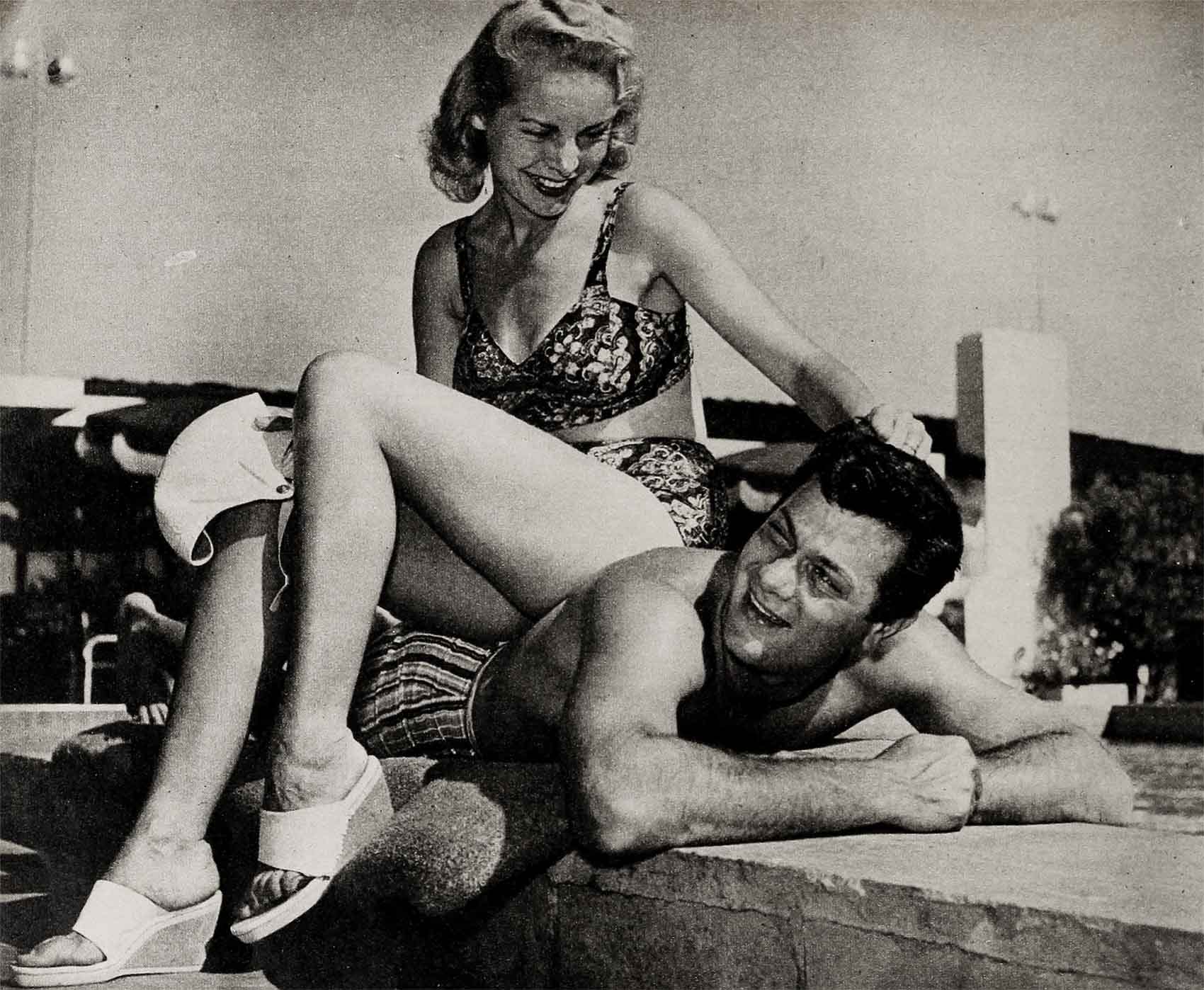

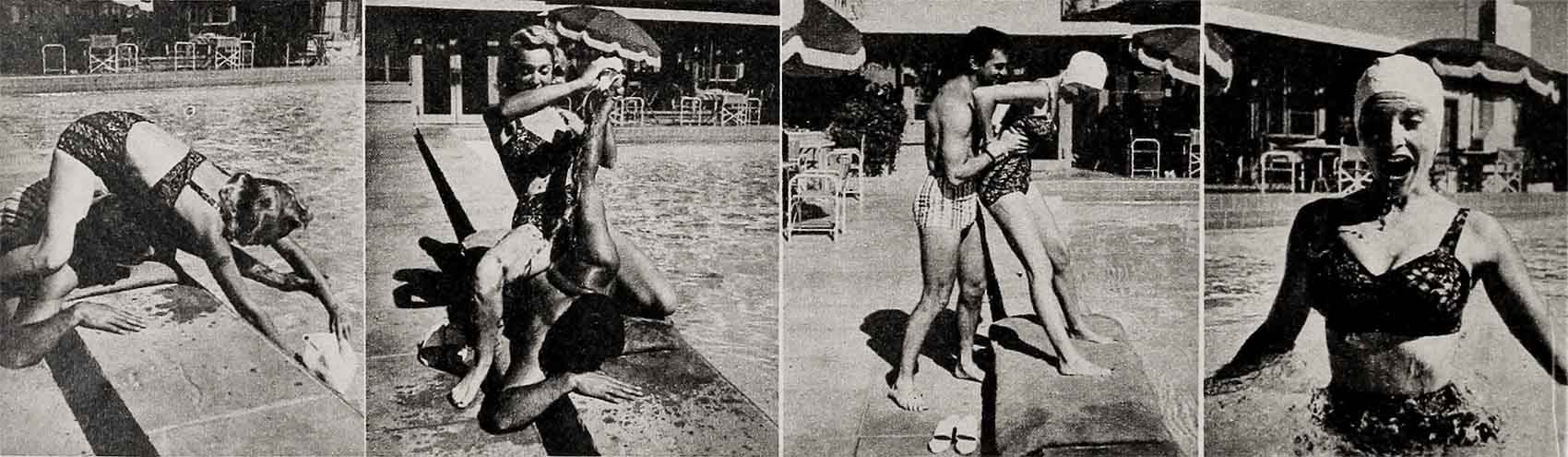

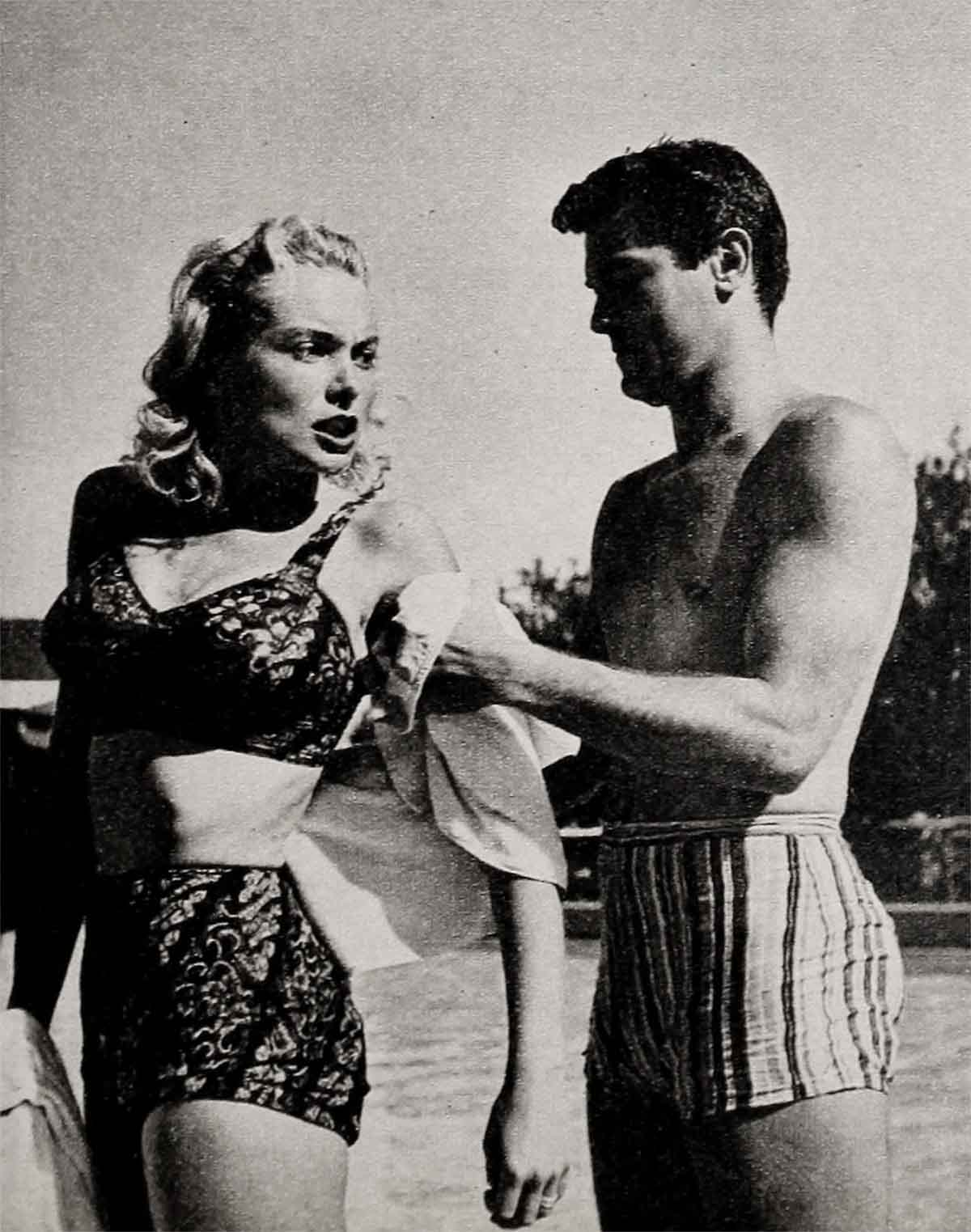

“She must,” replied Janet, sitting down right in the middle of his back. She pulled at his ears, filled her bathing cap with water and poured it over his head, and said “Nope!” when he told her to quit. Suddenly Tony rolled over, pulled Janet to him in a short hug, and in the same moment practically gave her a shove toward the pool. She screamed, tried to catch her balance and couldn’t make it. There was a splash. When someone came up and asked what was wrong Tony replied, “I never did care for that girl.” Janet was already swimming the length of the pool in a beautifully smooth crawl and his eyes were following her with obvious admiration.

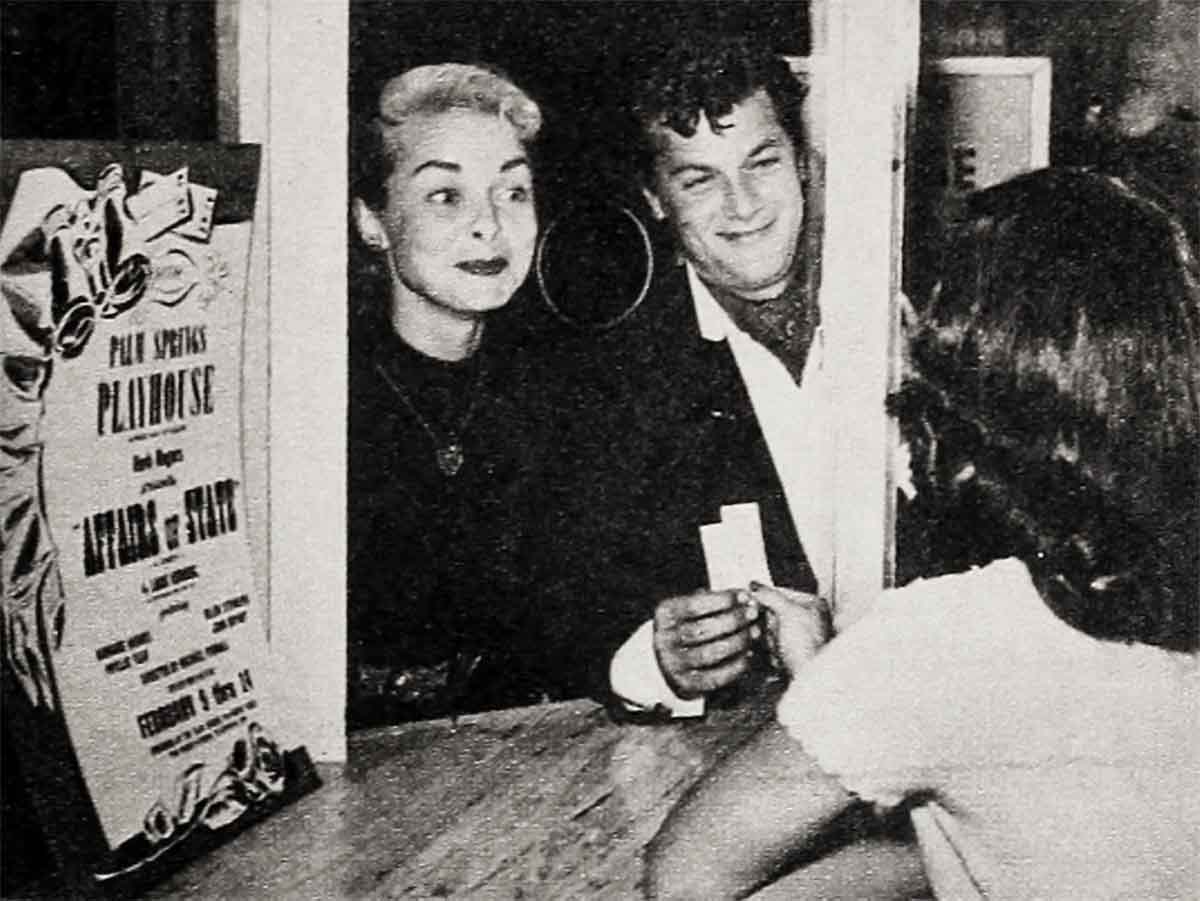

For more than a year Tony and Janet had been trying to get a few weeks off for a vacation; last spring they finally made it—or at least ten days of it—down to Palm Springs after they finished their second costarring picture, The Black Shield Of Falworth. Janet was pounds under her normal weight and Tony was really worried about her. Janet admits he had reason. “I was on the verge of vanishing into thin air,” she confessed. “It’s true, though I don’t want to be hysterical about it, that I was near collapse when we climbed into our blue Cadillac convertible—please forgive me; we haven’t had it long and I sound like I’m bragging but we’re both so crazy about it!—and rolled down to Palm Springs.

“I’ve heard people snickering when they hear of overworked actresses. The usual reaction is: Well, now, isn’t that too bad? The poor girl only has to work about forty weeks out of the year, has hairdressers, make-up artists, servants at home, a doting husband, gets paid scrambled thousands of dollars a year and then tries to talk herself into believing she is about to fall over from nervous exhaustion!

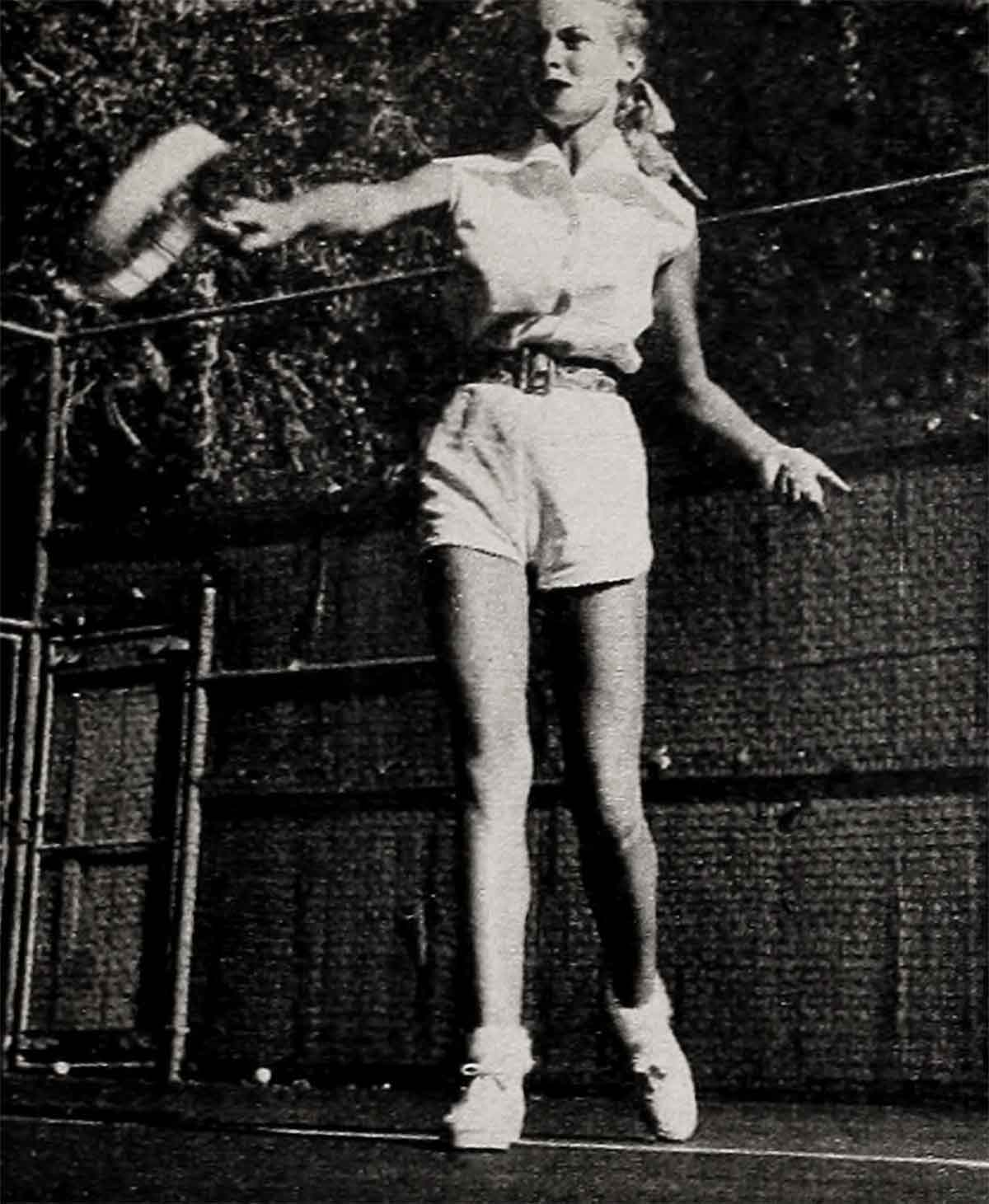

“And maybe they’re right, but I don’t think so. Tony and I have gone from one picture into another. We don’t think we’re great thespians, but on the other hand we work at it; we must memorize pages and pages of dialogue and we must do dozens of things we’ve never done before—and do them convincingly. For my pictures I’ve had to learn how to milk a cow, drive a team of horses, run an old-fashioned sewing machine, toe dance, tap dance, ballet dance, ride western, ride English, ride sidesaddle, ride bareback, handle parachutes, train lions—and I’m expected to look like an expert at it! Tony has had even tougher assignments than mine. Is it so hard to believe that after steady weeks, months, and yes, even years of this, you could get a bit weary?”

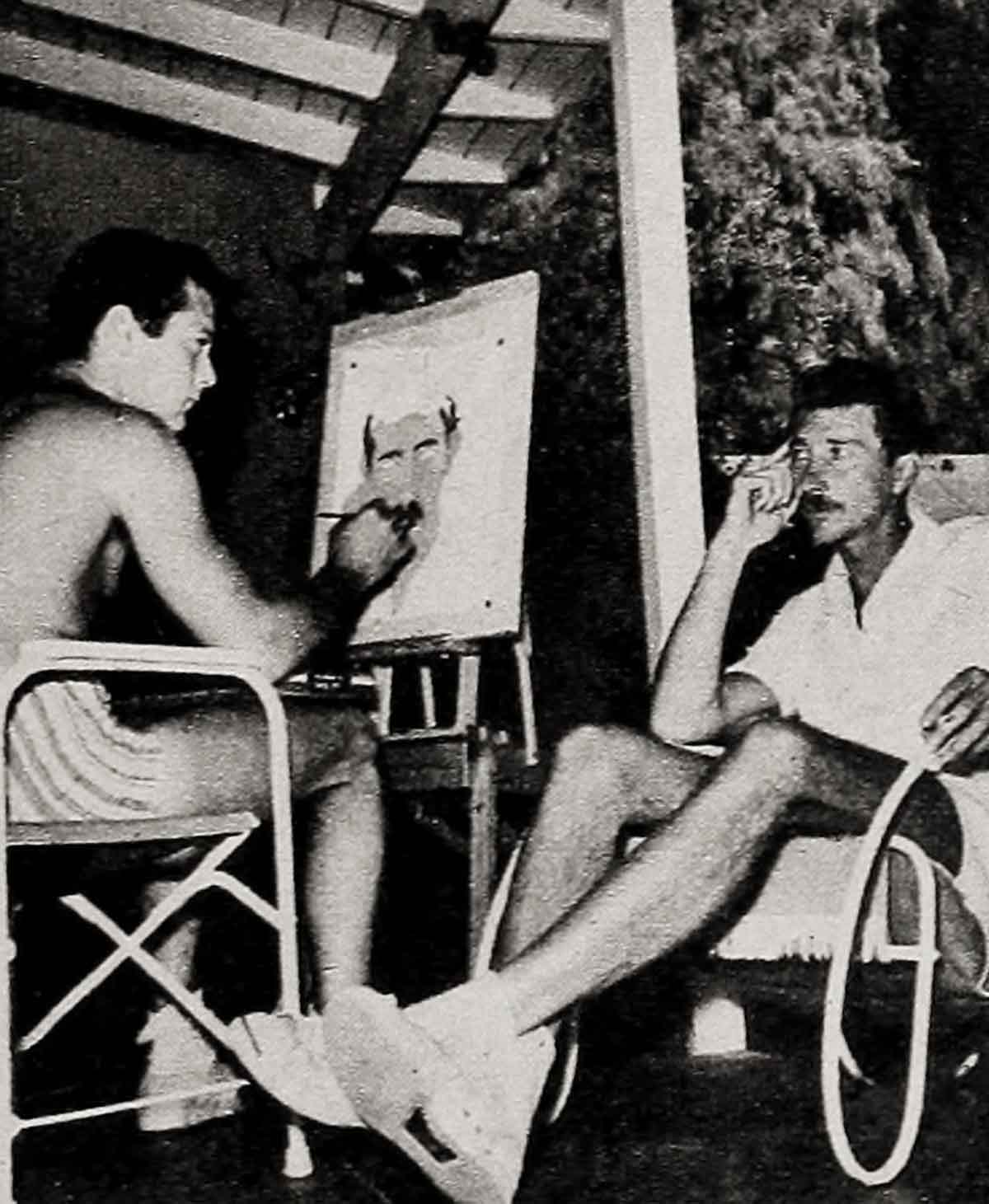

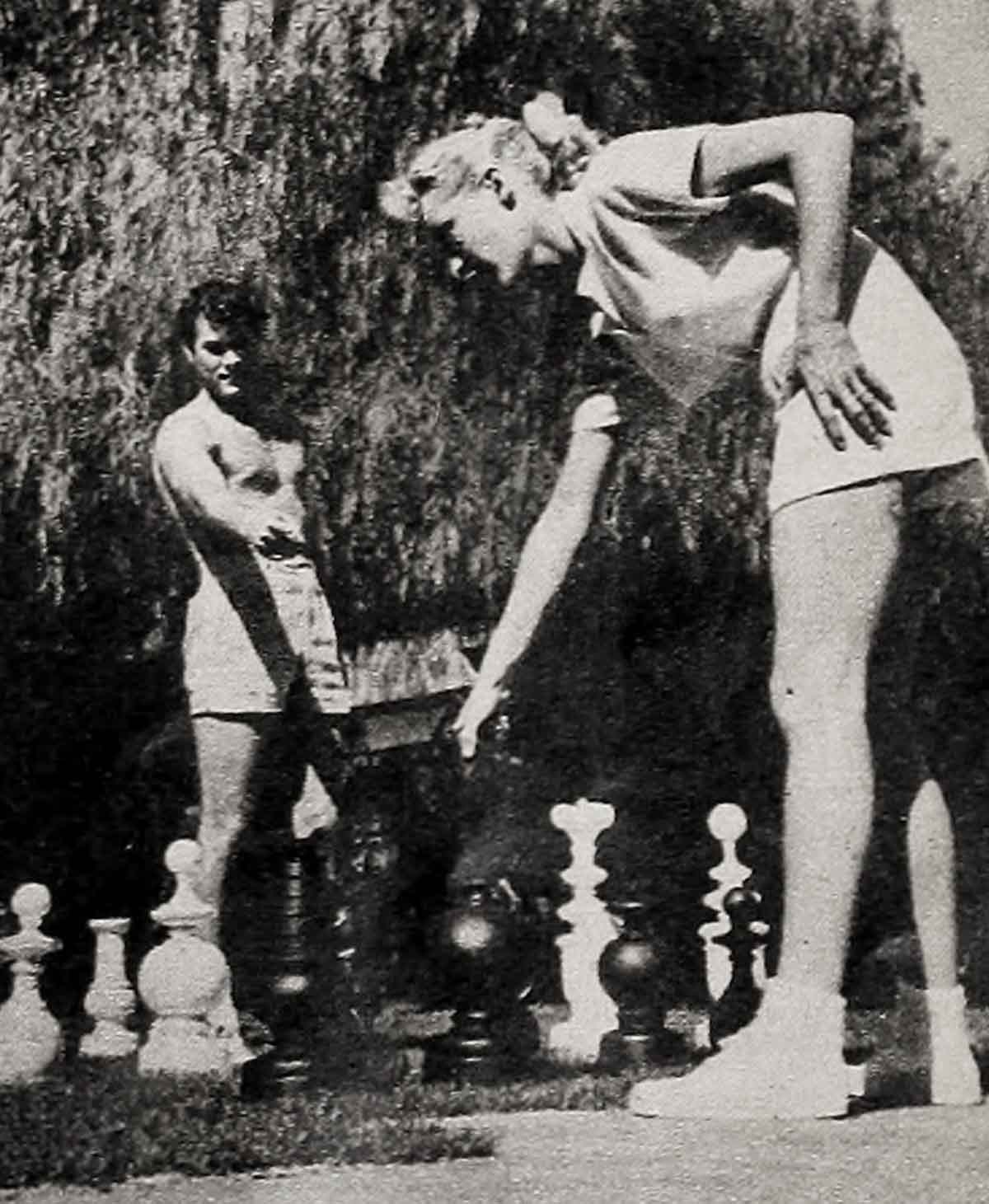

So they swam and took the sun and lazed around. Tony had a chance to catch up on his painting, even to try to finish a study of Janet he had started more than a year before in Colorado. And they caught up on talk—not studio talk which is mostly on their tongues when they are working, but small talk—the little things about each other that each wants to know and can’t find out when they are busy at the studio.

“Why don’t you ever imitate Cary Grant’s voice any more when you telephone me?” she asked one afternoon.

“I don’t have to now,” he said, “because I know you won’t hang up on me. That’s why I used to do it then.”

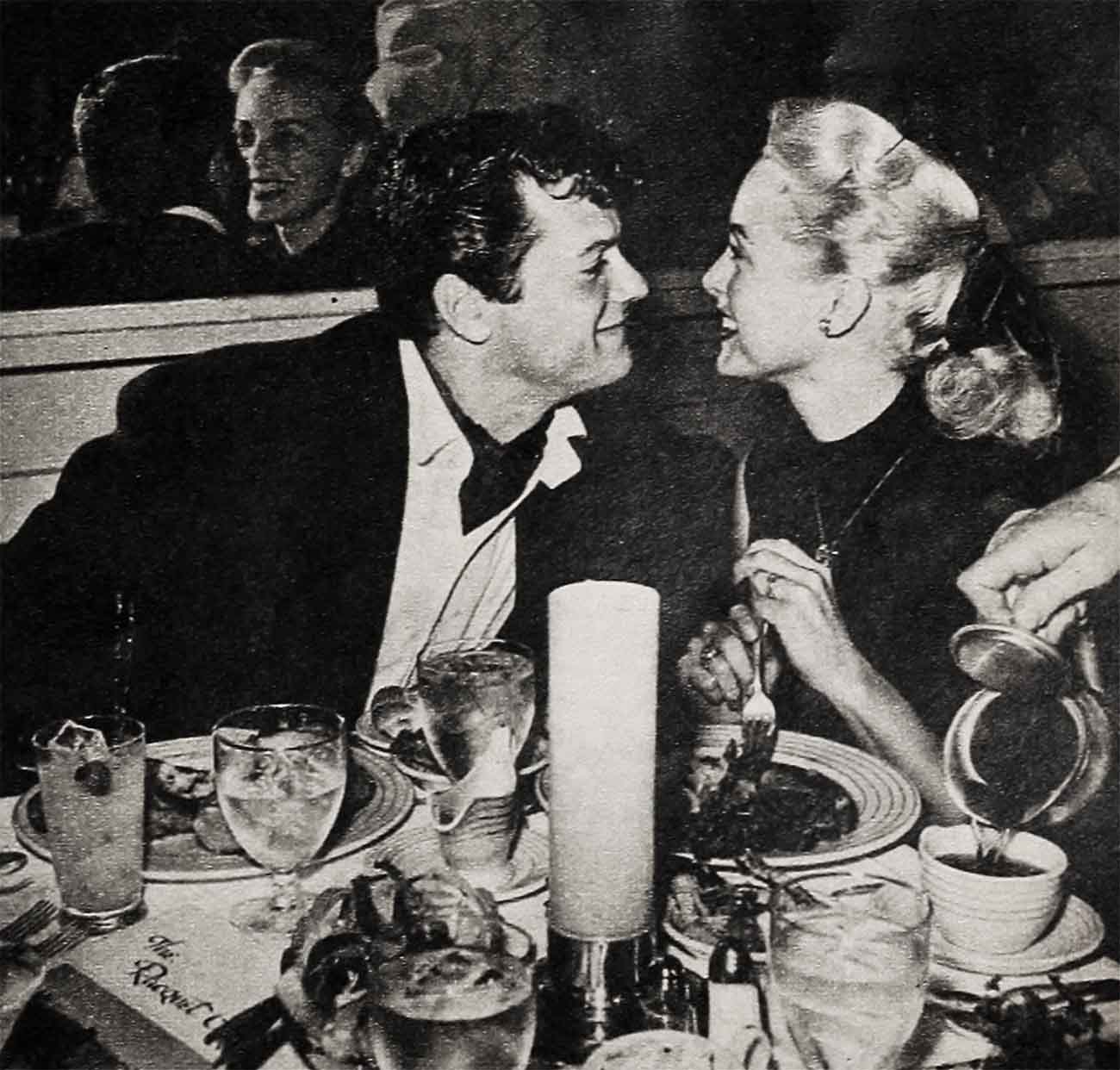

About the third night after their arrival they decided they were strong enough to do a little dancing, and in a dreamy moment Tony wanted to know how Janet could be sure she was still interested in him.

“Funny you should mention that,” she said, “because one of the ways Id know whether I still really have ‘it’ for my husband is whether or not I still like to dance with him; whether when the music gets real soft, so do I, and whether I have that real gone feeling when I’m in his arms.”

“Well?” he asked.

“Well, what?” she wanted to know.

“Well, you know what,” he said.

“Yes,” she said, and buried her face deeper in his shoulder.

Walking home from the movies one night they met an old New York friend of Tony’s who said, “Well, so long, you old car thief.” Janet was curious. As soon as they were alone she wanted to know about that. “That man was kidding, of course.”

“No, he wasn’t kidding,” Tony told her. “It’s true. I—I was a car thief in New York. Dum-de-dum-dum!”

Janet laughed, but her hand was at her heart and she was already wondering where they might find a lawyer to fight extradition. Then Tony explained. He put his arm around her and picked the shadowy places on the street to walk through while he told her the story. It wasn’t automobiles he had stolen, he said. It was a trolley car—a full-sized, Third Avenue trolley car. He was nine years old then.

“But why?” asked Janet.

“It was a slow afternoon,” replied Tony, “and I had nothing else to do. A bunch of us kids were wandering around and suddenly we found ourselves in the car barns on Third Avenue in the Sixties. Somebody said something about liking to go for a ride so I got in one of the cars and—it was so simple—a couple of gadgets to work and the car moves. Who could resist working them? First thing you know, I was running the trolley down the street!”

“What did the car people do?” asked Janet.

“They chased us—in another trolley,” Tony said. “I slammed on the brakes and we all jumped out and scattered. End of story. End of criminal career. What’s your reaction?”

“I think that before going to bed I’ll have a chocolate fudge sundae,” said Janet.

“Poor thing,” said Tony, comfortingly. “I don’t blame you. I’ll have a salami on rye with cheese.”

“I’m not going to try to do anything more about the way you eat,” Janet told him. “I think you could digest granite with the right seasoning.”

“Sure,” Tony agreed. “The salami people pay me for the endorsement. If I tried to eat frou-frou salads like you I’d disappear like Judge Crater. By the way, who was Judge Crater?”

“A guy who disappeared,” said Janet.

Tony stopped short and waved his arm at all of Palm Springs which lay before them, dark and sleeping under its rustling palm trees. “Between Janet and me,” he announced to whom it might concern, “we know everything.”

Among the friends they met there was Ed Trzcinski, one of the writers of Stalag 17. Tony did a nice portrait of him. Ed was so pleased that in return he offered to teach Tony enough Freud to enable him to psychoanalyze Janet. Tony refused.

“I don’t want to analyze her,” he said. “I just want to idolize her. And I know I can’t have both.”

“That’s the nicest thing you’ve ever said about me,” Janet told him. “I think.”

There were serious interludes, too, during the vacation, like the afternoon Tony revealed to some of their friends that he and Janet were not at all unmindful of their future and the necessity of planning.

“We have a feeling that one day we might want to pull. up stakes and maybe go to New York, produce our own picture abroad, or something like that,” he said. “If that turns out to be the case we don’t want to be walking around with a mortgage and a pair of worried looks. We want to be able to take off in a couple of days.”

“So that’s why you rent a house instead of buying, eh?” he was asked.

“One of the big reasons,” he replied. “We could slap enough money down now to ‘go into escrow’ on a mansion somewhere, but it wouldn’t be wise. Outside of the fact that we want mobility, we want to be liquid. I mean we never want to have to accept a role just because we need the money for our obligations, real estate or otherwise. We owe it to our professional selves to keep out from under pressure and to determine all our moves by artistic considerations. We don’t want any of our followers to have to see us do anything which is not suitable for us and which we would not do well.

“For instance, even though Janet and I partnered up for Houdini, and we fit well into our next co-starring picture, The Black Shield of Falworth, we are not a team by any means. Just because Houdini did wonderfully at the box office and they predict the same thing for The Black Shield Of Falworth, doesn’t mean we should work together again—not ever if the right roles don’t come up. We are essentially just two people who happen to be married, not an actress and an actor who married because it was a smart thing to do professionally.”

Everybody said Tony had the right idea, but a girl who had been listening to him asked Janet if this reasoning suited her. “After all, you want your home and your homemaking now, don’t you?” she asked.

“I have my home now,” replied Janet. “It’s a rented one, but if Tony and I hadn’t been fortunate enough to be in pictures, and be making the salaries we do, a rented home would have been all we could afford anyway. And we’d have loved it!”

“Yes, but a home that isn’t your very own, really your own, doesn’t feel the same, does it?” asked the girl, persisting. “I mean nothing has a sense of permanence and you don’t feel it’s a place with all the things that, well—like the song goes, ‘All The Things You Are.’ ”

“All those things we’ve got and we’re still getting,” Janet assured her. “We’ve got probably the only eight-room bungalow in Beverly Hills with only one bedroom. Don’t you think that’s individual? Everything except the dining room, living room and kitchen has been turned into a den, nook or plain hideaway. Of course we call them the bar room and the trophy room and what not, but they could turn out to be nurseries!

“In the meantime our little memories are accumulating, if nothing else. I love to be in the bar room sewing when Tony gets home from the studio. It’s like a little ritual as he moves around, letting me know he’s home in his own way, going about the business of forgetting his workaday world and fitting back into the role of husband and man of the house. He does it with a kiss, with a word about this and that, with the strange, gentle jazz music he likes to turn on every night. I’ll say, ‘Will you have a little glass of wine?’ And he’ll reply, ‘Can’t I have both?’ And I’ll ask, ‘Meaning?’ And he’ll say, ‘Meaning you.’ ”

What Janet knows about Tony, and likes to make plain, is that he doesn’t think actors should be stable—like bankers. “The thought frightens me,” he has said. “The minute you are settled, then you no longer want to gamble. To young people like Janet and me the picture business is still great adventure—like the wildcat oil business. We both know this may not be a sensible viewpoint but we are both for actors not being too sensible.

“I know I could be criticized for this but I don’t mind. I don’t mind almost anything reporters have to say about me. I’m lucky to get my name in print, if you ask me. Sometimes, however, I wish they wouldn’t get off on a wrong kick like with that thing about Jerry Lewis and me feuding. You know how that started? Aw, what’s the difference? If stories like that can get around about two old friends none of us has to worry about being too stable.”

On the tenth day after their arrival at Palm Springs Janet and Tony went out to the pool to soak up a last dosage of sunshine. Charlie Farrell, their host, came by to lark around with them and bid them godspeed. A messenger walked out on the lawn paging, “Mrs. Tony Curtis,” and handed Janet a package. Janet and Tony always open packages when they are delivered. She had to show it—an inscribed cigarette case for him.

“I hadn’t meant to give it to you yet,” she said. “The boy had to bring it out here!”

“Well, it’s a nice present,” he said. “But what’s the occasion?”

She thought for a moment. “Oh, I haven’t figured that out yet,” she said. “Would St. Patrick’s Day do?”

Tony responded to the best of his ability and then lay back in the sun again, closing his eyes. Janet leaned way over.

“I know,” she said. “Him’s baffled at me.”

Tony reached up and around for her.

“Always,” he said.

THE END

—BY LOUIS POLLOCK

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE JUNE 1954