Audrey Hepburn: “My Husband Doesn’t Run Me”

Audrey Hepburn’s famous urchin hair-do had disappeared, and her smooth dark locks, now long, were twisted into a pony-tail. But front-face, with her ragged bangs framing her inimitable elfin face, she still looked like a little boy.

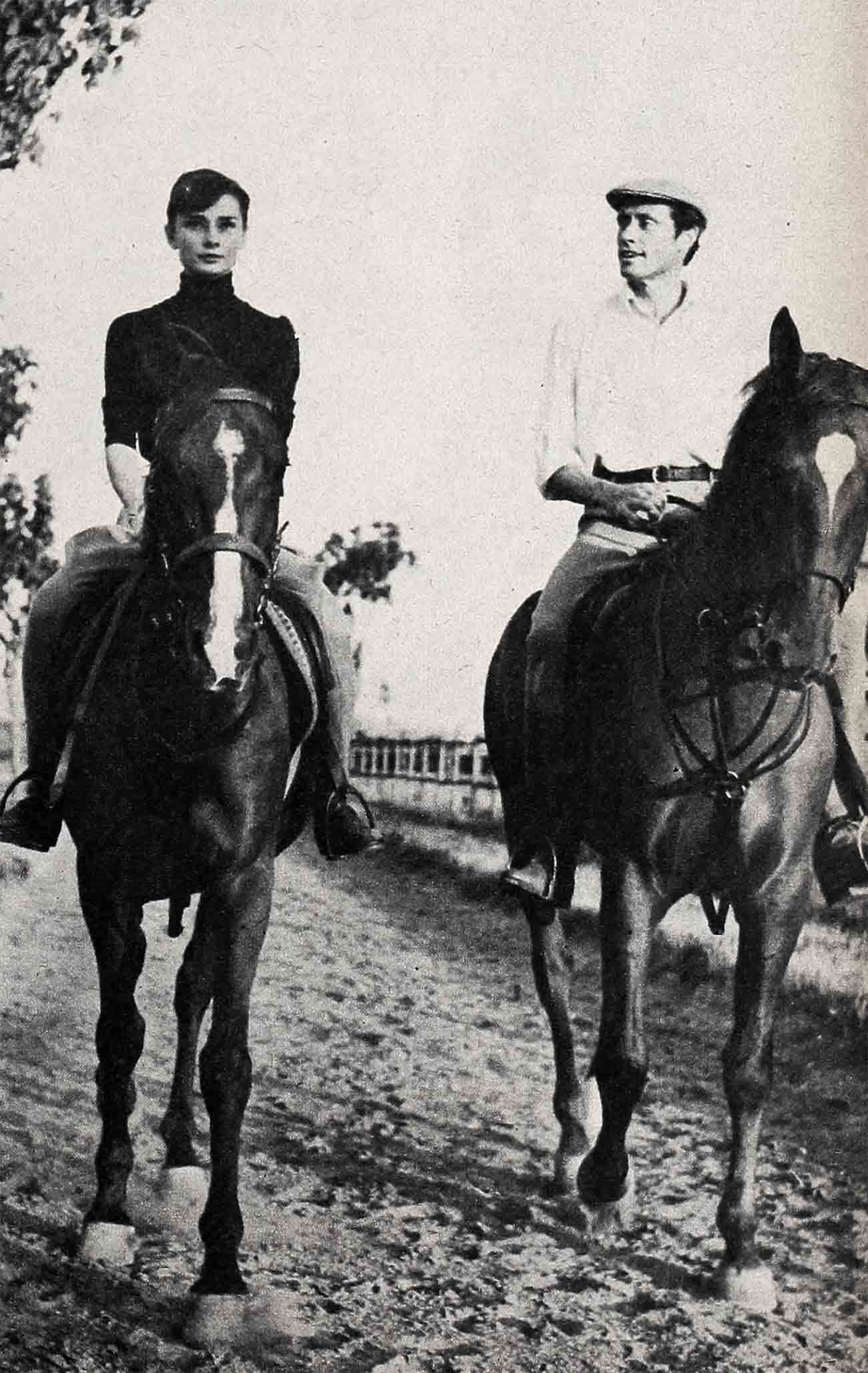

Audrey was in Paris, after six months of grueling work and intense concentration as the heroine of Paramount’s ambitious production, “War and Peace.” She was taking a well deserved rest, while Mel Ferrer was exchanging sword points with French actor, Jean Marais, for the screen love of Ingrid Bergman in Jean Renoir’s “Ellena.” Audrey and Mel were still happily conforming to their design for living, quietly determined not to let the demands of their careers separate them.

Rarely has there been such excited and heated controversy about a star as there has been about Audrey Hepburn. Newspaper and magazine writers have discoursed at length about her dislike of being in the publicity spotlight. Movie critics have shouted that she jeopardized her career by staying off the screen so long. Gossips have insisted that Mel Ferrer is a modern-day Svengali, completely dominating Audrey and controlling her every word and move.

Most of this tongue-lashing has come from persons who have never even met either Audrey or Mel. But this hasn’t prevented them from having certain pre-conceived ideas about them. Because Audrey rose to stardom so fast, they predict that her fall will be just as rapid. Because she is bewitching, enchanting and utterly charming on the screen, they insist that can’t be her real personality.

Actually, in spite of what the cynics and over-imaginative, unknowing gossips would have others believe, Audrey is just as delightful and gracious in person as she is scampering over a movie screen. Her simplicity of manner, poise, and gentle warmth shine through the screen because they are her own inbred personal qualities.

Audrey has no reason to apologize to anyone. She has conducted her personal life with dignity and reserve and has pursued her career according to the dictates of her own principles. But, like anyone else in the public eye, some of her actions have been misconstrued, and she is anxious to put the record straight.

“Mel and I both value our careers immensely,” Audrey said thoughtfully, as she poured two cups of steaming French coffee, and dug with relish into a box of rich Dutch cookies. “We’d be very foolish and irresponsible if we didn’t. Nevertheless, our own personal happiness has first call over any other factor in our lives. I don’t know if the situation will ever arise, but if it were really a question of our careers separating us and interfering with our happiness together, we wouldn’t hesitate as to choice. No, we wouldn’t hesitate because it would soon become a vicious circle. If we ever said, ‘Oh, just this once, what does it matter if we’re separated for a few short months,’ then the once became twice—without realizing it, we might have let material success ruin two lives.

“I don’t think whatever job we went off to do under those circumstances would be terribly well done,” Audrey said earnestly. “I think we’d each have a very heavy conscience.

“It seems most unlikely that the demands of our careers will force us to work apart,” she continued, flashing her winning smile. “It’s so rare, you know, the kind of opportunity that is irresistible—the greatest script, the greatest director, and everything else we cherish professionally—and that Mel and I should both find it at exactly the same moment and at opposite ends of the world.

“It might easily happen, though, that pictures will overlap, and circumstances would part us, if only for a little while.” Audrey’s face clouded at such a prospect. “It’s impossible to answer how we would react. We would both have to sit down and figure and reckon, put it on the scales, and see how it weighs up, balance the advantages against the disadvantages, the conveniences against the inconveniences.”

Audrey knows one thing for sure: No matter what she’d decide, Mel would be right behind her, backing her up all the way. “He’d never want me to sacrifice any part of my career,” she said. “On the contrary, he’d say, ‘Let’s approach this from a positive point of view—how can we arrange our schedule so we can be together as much as possible.’ And we’d scheme and juggle to find some way to reach a compromise—and each one of us would give in a little. You have to each give in occasionally in marriage—what difference does it make, if the reason is right?

“I have faith about these things,” Audrey continued. “I believe that if I do something for the right reason, there has to be a blessing on it. I’m not saying that in any fatalistic way, you understand. I don’t mean that I just sit back and let come what may, confident of the result because of the justice of my motives.

“It’s just that I don’t really believe in making a decision or planning an act if it’s for a wrong reason. If I were asked to take a step which might jeopardize my marriage, I would delve deep down into my heart to discover why I must do this. If a selfish advancement of my career at the risk of hurting Mel were at the bottom of it, I’d say ‘no.’ The reason must be right.

“Oh, don’t think it’s as easy as I make it sound,” said Audrey with a laugh. “It’s not just by chance that Mel and I are both in Paris at the same time now. After Billy Wilder discussed the possibility of my doing ‘Ariane’ here, Mel began to study the Paris front. And we were very lucky because he was offered the lead in ‘The Life of Modigliani,’ the story of the famous French painter. So then I said to Billy, ‘I will do it.’ Now the starting date of ‘Ariane’ has been delayed because of Billy’s working on ‘The Spirit of St. Louis.’ In the meantime, Jean Renoir called Mel and asked him to play one of the leads in his new picture with Ingrid Bergman. As a matter of fact, Mel won’t begin “Modigliani’ until April, just as I go into ‘Ariane.’ So you see, we’ve arranged for our schedules to coincide without in any way interrupting our life together.

“As I say, you’ve got to have a lot of faith and a little luck. It won’t always be this easy, I know. There may be a time when we will find ourselves in one of those inextricable situations: while one of us is working here, a great offer will come from Hollywood, saying, ‘Will you or won’t you come—we begin shooting in two weeks and we must know by tomorrow?’

“Do you go, or don’t you go?” Audrey stopped suddenly and gazed out the window at the peaked Paris rooftops. Then she shook her head and sighed resignedly, “I don’t know what you do!” she admitted. “Our careers mean a great deal to us, but I must emphasize, what carries the most weight with us is our personal happiness. It has to be that way. Otherwise, we should not have married in the first place.”

Audrey’s usually placid nature rebels at the mere insinuation that Mel is trying to run her career, or that he is using her success as a stepping stone to advance his own. Her soft voice rose in fury as she recalled some of the accusations that have been thrown at Mel since their marriage.

“How can people say that Mel makes all my decisions, that he decides what I am going to play, and with whom, and where! It so infuriates me. I know him so well and am so close to him. I know how scrupulously correct he is, and how he loathes to give an opinion unless I ask for it. This is because we want so badly to keep our careers separate. We don’t want to interfere with each other. For that reason we have different agents.” Audrey emphasized her words with biting exactitude.

“And then what about me?” Audrey smiled quizzically, but beneath that gentle smile emerged a hint of the spirit that made her, when still a child, defy the Nazi occupation of her native Holland to carry dangerous messages for the underground forces, the fierce pride that stifled her convictions of all her physical shortcomings and bore her straight to stardom.

“What about me?” Audrey repeated softly. “I’ve been fending for myself since I was thirteen and thinking very carefully about a lot of important problems, and I don’t think I’ve made many bad decisions. I’m very proud of that, about my ability to think for myself, and no one, not even my husband, whom I adore, can persuade me to do something against my own judgment.

“For example, recently a story came up which Mel sincerely felt I should have done. He didn’t try to persuade me; he just gave me his reasons for thinking the way he did. I thought about it very seriously as I do about every story submitted to me. But I couldn’t in all sincerity accept his convictions. I refused it. Mel didn’t change his opinion; he thought I had made a mistake, but he wouldn’t for the world have tried to pressure me.”

Audrey and Mel are bending over backwards to keep out of each other’s professional lives—not to please others, but because they want it that way. Yet, it may happen, as it did with “Ondine” and “War and Peace,” that they will play together.

As Audrey said, “Why shouldn’t we, if the parts are right and the casting is logical and natural? But in that case, we don’t feel it is necessary to defend ourselves.

“Mel was accused of getting a role in ‘War and Peace’ simply because I was in it. Actually, he was asked to play the part of Prince Andrew long before I was even approached—as a matter of fact, before we were even married, while I was resting in Switzerland! So there was never any question of ‘get him and you’ll get her’ as has been reported.

“It was many months after Mr. DeLaurentiis had queried Mel about being in ‘War and Peace’ that I was asked by King Vidor to accept the role of Natasha.

“I was unable to commit myself at the time,” Audrey explained, “because Mel and I were planning to make the screen version of ‘Ondine’ in London. Then the project fell through because of all kinds of complications over the original French rights. Neither of us had anything planned. Suddenly, we thought, ‘Why, there’s “War and Peace”; perhaps it’s not too late.’ ”

Audrey and Mel were vacationing in St. Moritz when Dino DeLaurentiis contacted them by phone. “My preparations are made, and I’m ready to go,” the Italian producer told Mel. “King Vidor has his heart set on Audrey playing Natasha, and you know I’ve wanted you for a long time for the part of Prince Andrew.”

“Audrey and I aren’t sure we want to work together,” Mel answered, “but we’ll talk it over.”

That night, Audrey and Mel phoned Hollywood and explained the situation to Kurt Frings, Audrey’s agent. He agreed to catch the next plane for Milan, and they wired DeLaurentiis.

A little village on Lake Como—within commuting distance of St. Moritz and the principal cities of Italy—-was chosen as the most convenient spot for their discussion.

“We all assembled in a tiny hotel room,” Audrey recalled. “Mr. DeLaurentiis, King Vidor, Kurt Frings, Mel and I. For three hours, King Vidor talked about the film, and we were fascinated. He outlined exactly how he intended to make this great classic.”

Then Audrey, climbed into a car and drove around the lake, to talk it over, while DeLaurentiis and Vidor did the same thing in another car. After a while, Vidor joined the Ferrers in their car and Frings got into the other car with DeLaurentiis, to iron out some details with the producer.

Finally, in the wee hours of the morning, Audrey and Mel agreed to do the film. “After it was decided,” Audrey continued, “Mel and I were thrilled and happy at the thought of being in the same picture together. But from that moment on, we were put on the defensive. Imagine! Two married people, in the same profession, whose interests and careers are parallel, having to give excuses and explanations for playing in the same film together!” Audrey was indignant at the thought, and she sprang from her chair to pace up and down the room.

Then, just as abruptly, her mood changed, and she laughed gaily. “I suppose I shouldn’t take things so seriously,” she said, “but it’s so difficult sometimes to get one’s views across.”

Unveiling their private lives is part of the price stars must pay for the great rewards they receive, and no one is more aware of the importance and value of publicity than Audrey Hepburn. She has always made a point of fulfilling requests for interviews and pictures—after a movie is completed. But she agrees with most actors that, when publicity interferes with if one’s work, it has to take second billing.

Audrey is a serious actress, and when she is working she is completely absorbed in her work. This need for full concentration leaves no room for interruptions. During the production of “War and Peace,” she rose every day at dawn in order to be on the set, made-up and in costume, by nine o’clock. She greeted everybody each morning with her radiant smile, and every night, after a day’s shooting, she would flash the same smile in saying good night. But during the day, on the set, she was no longer Audrey Hepburn; she was Natasha, the gentle, sensitive heroine of “War and Peace,” and any attempt to distract her from complete absorption in her part met with cold resistance.

“During the shooting of ‘War and Peace,’ ” Audrey explained, “reporters would often come to the set for interviews. They couldn’t understand why I was unable to sit down and tell my whole life story and then walk back into the scene and give a performance. To me it is just impossible. I am not able to do it.

“Can you imagine doing a play, for instance, and someone during one of the acts says ‘Just a moment, please,’ and you Stop? A stranger wanders on the stage, you shake hands, and then you all sit down and you chat. He asks you what you have been doing, how you feel and your future plans. Then after a while he leaves, and you are expected to go on with the play exactly as if nothing had happened.

“Of course,” Audrey added, “there are those who say, ‘But it’s not the same as on the stage. In a movie, you do the scenes individually.’ But that’s the whole point. That’s what’s so difficult. You must keep up the same thread of inspiration for months on end with all the normal and necessary interruptions of lunch breaks and rehearsals. You don’t have the good fortune of being able to pump it all into three hours. Believe me, to keep the continuity of emotions through months of production is a task. It permits no diversions.

“Then, too,” Audrey continued, thoroughly absorbed in what she was saying, “it depends on what type of scene I am called upon to act. If it’s one which requires no emotional expenditure, but just a physical act—such as running up and oe down the stairs—I couldn’t be more delighted than to sit and chat and let off steam and have fun. But those moments

were rare in a dramatic film such as ‘War and Peace.’ I may have offended people quite often by just remaining in my corner in gloomy silence when they came up to greet me with broad smiles. But they had come from the outside world, and they couldn’t possibly realize what I had been going through, that I had been frantically saying to myself for minutes on end, ‘I must remember that line, I must summon the tears.’ ”

Audrey paused for a moment, looking a little upset at the thought of having offended someone, then she continued talking. “I’m incapable of switching my feelings on and off like an electric light. Once I get into a mood I must keep it going. How can I sit and chat and grin right up to the moment the director says ‘Okay, action,’ and then be expected to play an emotional scene?” She sighed and shrugged her shoulders in resignation.

One day Audrey was rehearsing a particularly serious scene with Henry Fonda. She had been fretting about it for days.

At first Audrey stood in a corner of the set murmuring her lines to herself, and Fonda stood in another corner, saying his. Then they began to rehearse together. At that moment, some big shots strolled on the set, with one idea in mind, to meet Audrey and Fonda. They insisted upon being introduced.

“I forced a smile on my face,” recalled Audrey, “and muttered a few polite words, because I knew it was expected of me. But the scene was finished as far as I was concerned. The mood had disappeared, and the take became a matter of mechanically repeating lines.

“I’m sure there are actors, much better actors than I, who can cope with such a situation and not let it disturb them. Perhaps it’s because they are better actors. But I just can’t.

“I know there are writers who can sit and write a story in an office with typewriters going all around them. But there are others who have to be in a quiet room all by themselves. I’m that way. Why, there was a time when I even had a complex working in front of my fellow actors! But I’m getting better; I’m learning. I hadn’t much. choice,” Audrey grinned impishly, “I had about half the Italian Army, working as extras, watching me during exterior shots.

“Acting doesn’t come easily to me,” Audrey confessed. “I put a tremendous amount of effort into every morsel that comes out. I don’t yet have enough experience or a store of knowledge to fall back upon. Many of my reactions stem from instinct rather than knowing. So I must work very hard to achieve what I’m after. That’s why any kind of diversion throws me off the track.”

Audrey’s insistence upon keeping her life as Mrs. Mel Ferrer and her individuality as a human being completely separated from her career has, in the past, earned her some spankings from the press.

But Audrey finds it hard to believe that she should be denied the same right to her privacy that is enjoyed by the very ones who would like to violate it.

“The extremes Mel and I have gone to for seclusion are no more exaggerated than those of Mr. and Mrs. Jones who live next door. We haven’t locked ourselves up for days on end—that would be extreme. We just try to keep our lives within the same proportion of privacy and normalcy as everybody else does.

“We like to come home and relax after a hard day’s work, just like anyone else,” said Audrey. “After all, we play a part all day, and our home is the only place we can be ourselves.”

In Rome, Audrey and Mel lived in a comfortable, rambling farmhouse, filled with animals and pets, and dedicated to the quiet, simple joys of home life. This was their home, the only retreat they had from the uninvited. It was the valve which released them from the pressures of their work. Who can blame them if they guarded it jealously?

While most actors enjoy talking about themselves and glory in all the ballyhoo that goes with their profession, Audrey Hepburn is an exception. Although quite sure about what she wants out of life, she is modest about her own abilities and self-conscious about her shortcomings. She is an actress who prefers to talk about others in the business rather than herself.

“Interviews are often a chore for me,” Audrey sighed. “I find it embarrassing to discuss things which are emotionally very close to me, like my religion or personal faith. Also there’s a danger of one’s becoming a sort of egomaniac after a while by constantly talking about oneself. You know, it’s terribly important for me to get outside of myself, to open up my mind and think about other matters, to walk about the city, to read, to rest, to enrich my life.”

Since moving to Paris, Audrey has been following no rigid schedule. If Mel’s on the set and she’s alone, she spends her mornings answering letters and taking care of business. In the afternoons, she studies to improve her French—which, Parisians claim, is accent-perfect—or she reads, or practices ballet, or walks for hours.

In Paris, as well as in most other European cities, American actors enjoy an anonymity they don’t have at home, but there are always a few odd characters around to stir things up—such as the minkcoated, bejewelled matron, who spotted Audrey in a Paris store one day. Running

up to her, she grabbed Audrey by the shoulders, spun her around, and cried at the top of her voice, “But you are Audrey Hepburn, now aren’t you, aren’t you!”

“I was scared stiff,’ Audrey confessed. “Everyone had turned around to look at us, and I had a terrible temptation to deny my identity. I finally made my escape and fled the store in terror.”

No one realizes more vividly than Audrey what a terrible burden her fantastic rise to stardom has become. With three pictures, of which only two have been released, she has become a sort of legend. It is terrifying to think she can’t afford to make one false step. Yet what courage and daring she has!

When she accepted the role in “War and Peace,” she knew she had to compete with Napoleon’s retreat from Moscow. An actor is often lost in the shuffle in a great epic like that. But to Audrey it was a challenge, and once again she was right. Reports from Rome have Paramount chortling with joy over Audrey’s sensitive portrayal.

In “L’Aiglon,” the picture Audrey will make next fall, with William Wyler, she will play the son of Napoleon and Marie Louise. It takes courage for an actress to portray a boy on the screen. But Audrey is an adventurer, she is not frightened. That’s another souvenir the Nazi occupation of her native land left her.

Audrey’s long run on the Broadway stage in “Ondine” took her away from pictures for many months. The prophets of doom spelled the end of her celluloid career, insisting she was staying off the screen too long for a new star.

Although Audrey is hyper-sensitive and takes these criticisms to heart, they won’t influence her in changing her mind—if she feels she’s right.

“I believe in the picture itself,” she explained. “If it’s good and your performance is decent, it will be just as successful as if it had followed ten others.

“Of course, if there is a lapse of, say, five or six years between films, there may be people who would have to be reminded of your existence. But I think we are judged by individual performances. If you do a decent job, fans don’t mind if they haven’t seen you for ages.

“Anyway, I would never let the fear of being forgotten prevent me from doing a play if I wanted to, or taking a rest if I needed one,” Audrey stated.

Before she begins “Ariane,” Audrey and Mel will escape to their favorite haven of rest, amidst the cool streams and lush meadows of the Swiss mountains. “This is our annual health cure,” said Audrey. “Mel and I are still living off that month we had in Switzerland last year, and we are in much better health than we have ever been. My own mother says so, so it must be true. When I think I look well, she usually says ‘You‘ve got rings under your eyes,’ or ‘You really don’t have a healthy color.’ But even she agrees that I’m now in top form.”

In top form, and on top of the world, is Audrey Hepburn, the golden girl of the screen. The luster of her stardom shines stronger than ever, but it can never out-dazzle the glow that comes from her heart.

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE APRIL 1956

No Comments