Cheryl Crane Pleads

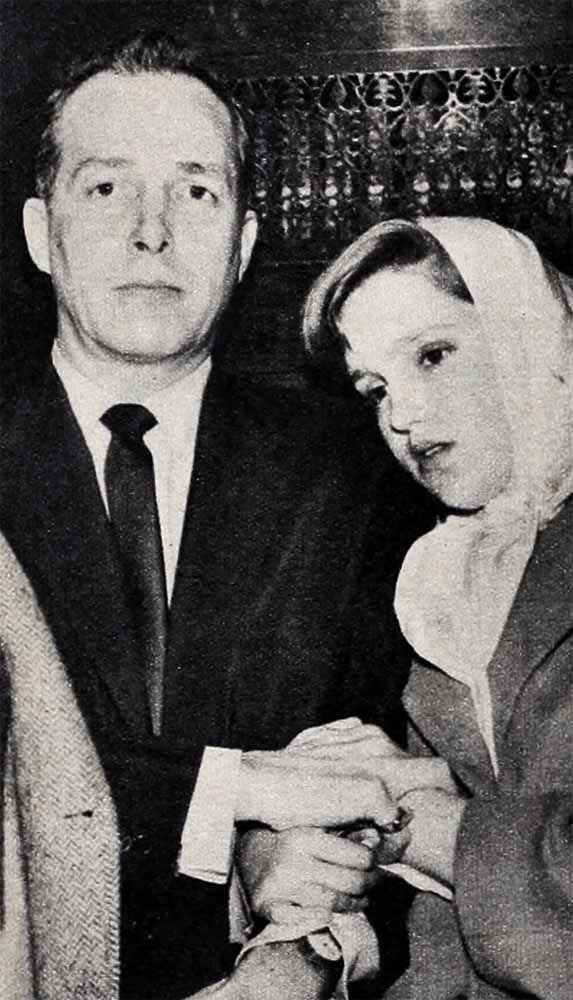

The Santa Monica courtroom was silent. Occasionally, one of the lawyers scattered around the palm-lined room would get up from a straight-back wooden chair and go over to the water cooler for a drink, breaking the silence for a few moments. Cheryl Crane sat quietly, hardly aware of what was going on around her, conscious only of the two people seated beside her—her father and her mother—each of them holding tight to one of her hands.

She didn’t look at either of them—even when her Dad, feeling her tension, and wanting to reassure her, squeezed her hand. Even then she couldn’t turn around and face him.

It seems, she thought, the only time we’re ever all together is times like this—when there is trouble. A fly buzzed by, interrupting her thoughts and breaking the silence, before flying out the open window once again.

Outside the close-door session of the juvenile courtroom, the mood was different. Hundreds of people had already gathered—some had been there since early morning, even before Cheryl had arrived, shy and alone, in the big black private car with the probation officers.

She remembered how they pushed towards the car and she tried shrinking back into the corner, hiding behind her large black sunglasses, trying to escape their stares.

It wasn’t that they were unfriendly. Some people had even called out “Good luck, Cheryl” as the deputy sheriffs helped her into the building, and the probation officers led her upstairs to the private chambers of Superior Judge Allen Lynch.

She was brought two hours early, to avoid the crowds, she was told. She knew that Judge Lynch was going to decide this morning who was to take care of her. Someone, she couldn’t remember who, had said that she was going to be placed in a foster home or a state institution. She didn’t believe them.

Suddenly, she stared down at her white shoes. She always wore flats; she was so tall, too tali for heels. Her mother had brought them with her dress, especially for today’s session, when she had visited her at Juvenile Hall. All the other girls’ mothers came on Sunday, but the officials said if her mother came with all the other parents she would cause too much confusion, so Mummy came on Saturdays.

Mummy looked pretty, even though her eyes were puffy and red from crying. / can never cry, she thought. I wish I could. Instead, she prayed her rosary—the one her father had brought her during last visiting hours.

It helped to pray. She still had her first Bible, the one mother bought her when she was a baby. I wonder where it is, she suddenly thought. I don’t remember unpacking it when we moved to the new house. Sometimes she took the Bible with her when she went to Mass with Dad on Sunday. One time, when she was young and going to St. Paul’s School, she even thought she’d like to be a nun—or a Catholic, anyway.

“I say my prayers regularly,” she had explained to Mother, when she visited last Saturday. They didn’t have much time together that day. The forty-five minutes went by so quickly. She explained to Mother that she couldn’t open the presents she’d bought—a gift box of shampoo and soap—until Sunday when all the other girls could open their presents. They talked about the classes she was attending and she’d asked if Grandma could have a blue ribbon for her hair sent in so that it would match her blue cotton shirtwaist dress—the one she was wearing today, for the session. She knew—and Mother did too—that the session was important, but they didn’t talk about it then.

Even this morning, when Mother and Dad came into the courtroom, they didn’t mention why they were there. But she could tell they both were upset. She could always tell . . . even when they tried to hide it. Daddy can pretend better than Mummy, she thought. He can always look calm.

Even the evening—that Good Friday evening—when the terrible thing happened to Johnny and she had called Daddy at his restaurant. He was having dinner, and at first, she had difficulty making the man on the other end understand who she was.

“I don’t want to interrupt him at dinner,” he kept saying, but finally, after she had repeated who she was, he did. She couldn’t remember much, except crying, “Daddy, Daddy, come quick, something terrible has happened. Don’t ask any questions, Daddy, just hurry, please.”

And then, right after hanging up, she suddenly thought: “But how does he know our house number? We just moved in Tuesday.”

She went outside and waited on the front steps, watching for his car. And it was lucky she had, because it turned out Dad didn’t know the number.

But when he got out of the car, he didn’t seem the least bit upset. All he said was, “Cherie, I’m coming,” and as she turned to run into the house to tell Mother—she hadn’t told her that she’d telephoned Dad—he called, “Wait a minute, Baby,” and he caught up with her and they went up the stairs together to mother’s bedroom.

She remembered seeing Johnny on his back on the floor. all she could say was, “I did it Daddy, I did it, but I didn’t mean to. I meant to frighten him. He was going to hurt Mummy.” And then Mother started to explain.

Afterward Dad put his arm around her and said quietly, “Cherie, I would have done the same thing. Everything’s going to be all right. Let’s go into your room and you put your head on my shoulder and have a good, long cry. Then, let’s have a real talk together. You’ll see, we’ll work it out together.”

And she knew, with Daddy there, she and Mother could. . . .

She wondered now, as she sat, watching Judge Lynch flip through some typewritten papers, whether, if Mummy, Daddy and she were always together, they would have these problems. once a lady columnist asked her: “Is your mother going to remarry your father, Cheryl?” Until then, she had never thought about it. As long back as she could think, the three of them had never been together.

She never asked Mother or Dad about the lady. There was one time when Mother took her and Lynn and Zan Barker to Daddy’s restaurant for a treat, and she remembered how Dad watched them and when Mother looked up and smiled he came right over and sat down With them. That’s what gave her the idea to ask Dad about the lady’s questions.

She had it all planned, once, one Saturday morning, when she was going downtown to meet Dad for lunch at his restaurant. They were going to celebrate over her report card. Dad met her, pretending to be casual like usual, but she knew he was pleased by the way he grinned.

They sat down at their favorite booth, the one in the far off corner—just the two of them—and talked.

She never did ask Dad about what the columnist had said. She couldn’t remember why. Maybe she had just forgotten, and then, later she thought maybe Daddy wouldn’t want to be asked.

Thinking back, she smiled. Horses or school, that’s what she and Dad usually talked about. Just like last Sunday when he visited her at Juvenile Hall: “I’d like to get on a horse and ride far away,” she had told him. And he had understood what she meant. He ’most always did.

She never told him but yet he guessed and knew, that sometimes she felt lonely. And one time when she had said, “I don’t think Mummy loves me,” he had been very firm. “You’re not being fair, Cherie,” he had told her. “You know what your mother. once told me? She said, ‘Every hour I spend with Cheryl is more precious.’

“Now, you’re a big girl and—even now—Mother has never left you alone, has she?”

And it was true. Thinking back, she could never remember being left by herself—not one evening.

This was one of the things Mother and Johnny had discussed that night, when they argued, and Johnny was mad because he thought Mother was going to dinner without him.

“How could I go out to dinner?” Mummy had said. “The maid doesn’t live in, and if I were going out, I would have to arrange with Mother so that she could either come to the house or Cheryl could go to her because she has never been left alone. . . .”

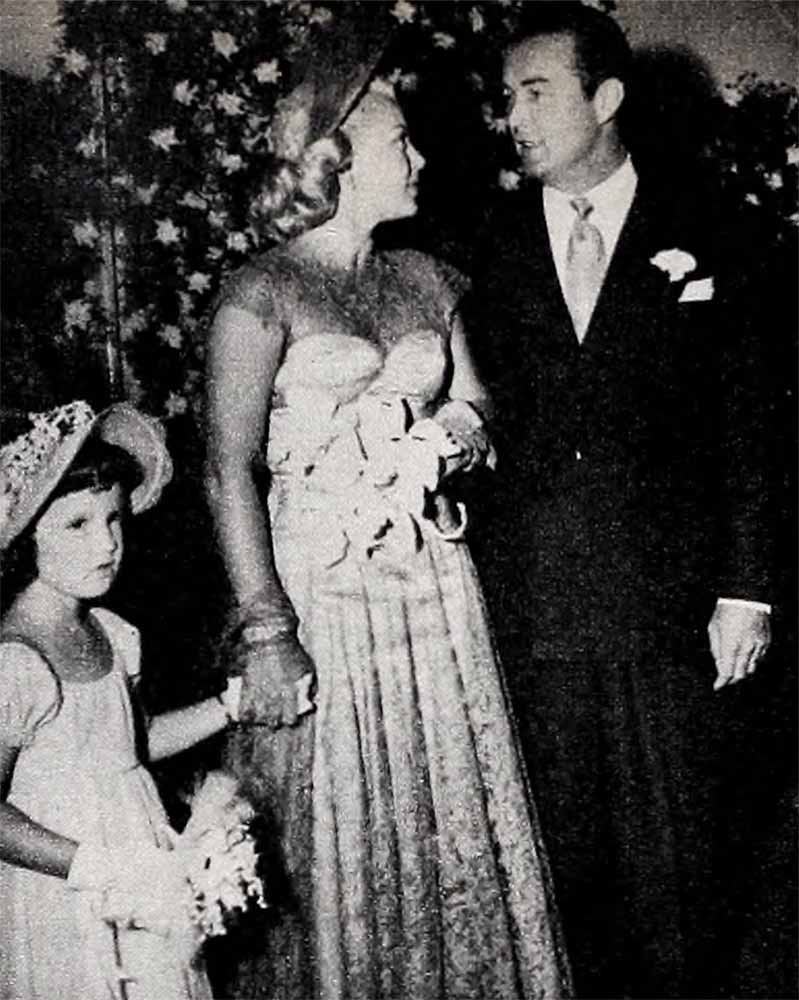

Mother was always worried about her being alone. “I want her to have a real home with brothers and sisters and a father,” she had said to Grandma when she called from Italy to tell them she and Lex were going to be married. “Lex knows how to handle children—he has two of his own.”

“And you’ll have a stepsister, Lynn, who’s your own age,” Mother had told her, “and you can go to boarding school together and be in the same class. Cheryl,” she had added. “You’ll never be lonely again.”

It was exciting flying to Turin, Italy for the wedding and meeting her new brother and sister and father. She’d called Lex Po right from the start. It was the closest to Pop. Since she called Father Pop or Daddy she didn’t want to hurt his feelings.

Lex was fun, she thought. When sometimes Mother was strict, he would say: “But let’s hear Cheryl’s side of the story.” Like the time she wanted to go on the Girl Scout camping weekend at Big Bear.

“You’re not old enough to be away on a weekend,” Mother had insisted when she stopped by after class at the studio and told her about the camping trip.

But when they reached home, Po came to her support: “Why not?” he wanted to know. “It’ll be great fun for her.”

And finally Mother did give in. “All right, Cheryl, you can go. I’ll take the station-wagon and drive you and your friends up myself.” Afterwards the kids had said how much fun Mother was and she felt so proud. She’d told them: “You’d really like my Mummy if you knew her.”

Mother was fun when she was happy, and she seemed happiest when she expected the baby.

“Guess what, Cheryl?” she had said one weekend when she returned home from school. “Come on upstairs. I have something exciting to tell you.” And she learned that she was going to have a sister or a brother.

“Oh, I hope it’s a brother,” was all she could say.

Grandma, she had noticed, was the only one who didn’t seem happy, and it was then that Grandma explained all about how her Mother had almost died when she was born.

“But how?” she had asked. And Grandma answered all her questions.

“Yes, even when the doctor had told your Mother she might die, she insisted: ‘I don’t care. I want her. I love her. I’m going to have my baby, no matter what happens.’ ” And she learned that for three months before she was born her Mother had been almost completely blind.

After that, and when Mother lost the baby, whenever she did anything wrong, she felt upset inside about hurting Mother . . . like the time she didn’t go back to Sacred Heart Academy and all the newspapers called up Mother and Dad and wrote it up and Mother was so upset.

I’d do anything to make up for it, she thought, as she turned and looked at her mother beside her, looking anxious but lovely in a beige shantung suit-dress. “Mummy looks prettiest in beige,” she thought.

Everyone thought Mother was glamorous and talked about her. In school, the kids didn’t know she knew, but she knew they talked about her mother and when she came in they’d be quiet—awfully quiet—right away and she’d know they didn’t want her to hear.

Not until the past weeks did she tell Mother that’s why she didn’t want to go back to Sacred Heart. And Mother had said: “Cheryl, you must always tell me how you feel. I could have arranged earlier to have you go to a local school and come home nights. I never want you to be hurt.”

Lately, ever since Europe and their Christmas holiday, she and mother had been closer than they had ever been. She had written Johnny to tell him: “Mother and I really had a wonderful time in Europe. I can’t remember when we’ve been that close. . . .”

She wanted him to know because she had once told him she didn’t think Mother really wanted to be with her and he had suggested that maybe she’d like to live with his stepmother in Woodstock, Illinois. It was after some girl at school had shown her a newspaper clipping saying her Mother didn’t plan to bring her over to Europe, where she was making “Another Time, Another Place,” for the holidays. But she had and they were together.

When Mother returned from abroad, from making the picture, they were just as close. Mother had even taken her to the Academy Awards Dinner.

They’d stayed with Grandma until their new Bedford Drive house was ready. She had had some dental surgery done and had to stay in bed and Mother cared for her since Grandma was working.

She remembered Johnny came over one afternoon while she was sick and she heard him shouting. Mother kept saying: “Will you please keep your voice down? Cheryl’s door is open.” And when she called, she noticed Mother was trying very hard not to cry as she fixed the solution for her throat.

Later on, she asked: “Mother, I overheard some of those things today. Why does Johnny say such things to you? Why don’t you just tell him that you’re finished? Are you afraid of him?”

“I’m deathly afraid of him,” Mother had answered.

And she had found out then what happened in London . . . all about Johnny’s threats and what he said about crippling her.

She couldn’t understand why her Mother couldn’t stop seeing him, but Mummy just kept saying, “Cheryl, it isn’t that easy.”

And all she could answer was, “Don’t worry, Mother. I won’t be far away.”

She wasn’t ashamed to tell the lawyers later, “I feel so sorry for Mummy but I did it to protect her. I love her more than anything.” Because she did.

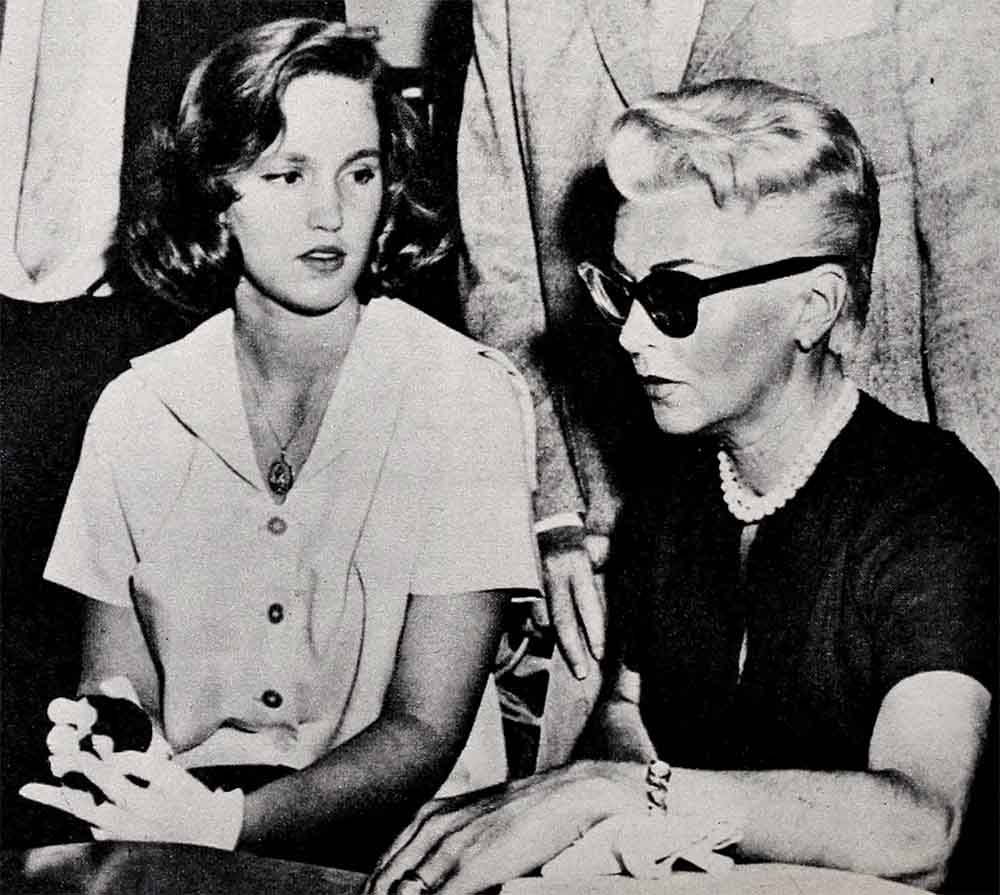

The clerk called Mother’s name and signalled for her to step forward. As she got up from her chair, Mr. Giesler, Mommy’s lawyer who’d been so helpful during the past weeks, leaned over and patted her shoulder as though to say: “It’ll be all right.”

Ali she could think of was that last visit at Juvenile Hail when Mother had said so gaily: “Just wait until after the hearing, Cheryl. First thing we’ll do is go to a drive-in for supper and then see ‘South Pacific.’ You’ll love it.” That’s a funny thing to think of now, she said to herself.

She couldn’t understand what they meant by “unfit” . . . but still it made her want to cry whenever she heard it. “How could anyone say such things about Mommy and Daddy?” she’d asked herself over and over. “What do they know?”

Once during the hearing, Judge Lynch was discussing her with a probation officer, and Daddy jumped up, almost knocking over his chair, and said loudly: “I am perfectly willing and able at any time to take care of my daughter.”

Now Judge Lynch was talking to Mother. Poor Mommy, standing there nervously twisting her lace handkerchief, her voice so soft it could hardly be heard.

The Judge must ha ve asked: “Are you going to continue acting or can you arrange to spend more time with your daughter?” . . . because Mother was saying, “I wish I could say that I had enough money put away so that I wouldn’t have to work. But I don’t. I must continue acting. It’s the only work I know and I have been the sole support of my daughter and my mother.”

Then it was her tum. The clerk called her name: “Cheryl Crane.” Suddenly she was scared, her heart pounding so hard it thumped in her ears. She sat there desperately thinking: Maybe if I don’t answer he’ll skip me and call on someone else. It was just like in school when the teacher called on you and you didn’t know the answer. You just sat there hoping something would happen—that somebody else would stand up and the teacher would forget about you. She wished she wasn’t always so shy—she could never talk to people like Mommy could—and now there were so many people looking at her.

Daddy noticed how pale and trembly she was and put his hand on her arm to steady her. As she stood up, her full skirt caught on a corner of the wooden chair, making it clatter. She blushed feeling so big and awkward. Then Mommy reached out, touched her hand and smiled reassuringly.

She couldn’t remember walking to the front of the courtroom but there she was—standing in front of the Judge. Self-consciously she tried to brush the wrinkles from her dress . . . I must make a good impression on the Judge, she’d been thinking all morning, . . . maybe it’ll help Mother and Daddy.

The Judge smiled down at her kindly and she felt a little better. The probation officer had said he would be nice—that he had two children of his own.

“I have in mind that probably something could be worked out where you could be placed under another name when you go to school. What would you think about that, Cheryl?”

She took a deep breath to keep her voice from trembling. Mommy had once said that’s what actors and actresses do when they’re scared. “No,” she answered. She was surprised when she heard her voice—it sounded so strong.

“You don’t want that?” asked Judge Lynch. “You’d rather stay here? And fight it out?”

“Yes, definitely,” she had repeated firmly.

“That’s courage,” the Judge said.

Later he had told her: “Just try and forget all this bother and publicity. Do you think you can do that?”

“I’ll try,” she said, thinking: “I can do anything if only I can be with Mommy and Pops.”

Then Judge Lynch said she could go back to her seat. She didn’t look at anyone as she walked back, she was afraid she might not have said the right things. She sat down and waited. It was almost time for the Judge to announce his decision.

The minute hand on the big wall clock moved, shattering the quiet with its mechanical click. She looked up . . . almost 1:30 . . . they’d been there 90 minutes.

Then the Judge began to speak: “. . . This Court grants temporary custody of Cheryl Crane to Mrs. Mildred Turner. . . . The Probation officers will determine the number of visits Mr. Crane and Miss Turner can have with their daughter each week. We will decide at a later time who will be granted permanent custody. The Court’s decision will be guided by the testimony of Probation Officers who have conducted an intensive investigation of her home life and by Cheryl’s own desires.”

Then the Judge rose and everyone stood up as he walked out of the room. Suddenly the Courtroom was filled with the sound of voices and chairs scraping as people moved forward to say congratulations.

Grandma rushed to Mommy and put her arms around her. They both tried hard to smile, then broke into tears. Mr. Giesler and Mommy’s other lawyers stood silently at her side.

She looked up and saw Daddy, white faced and unsmiling, his lips pressed tightly together, walk alone to the far corner of the courtroom. She tried to catch his attention across the room, to smile and try to make him feel better by letting him know she remembered what he’d said: “Cherie, baby, we have a theatre date the very first night you’re free.”

Grandma, who was to take care of her now, stood by her side but they didn’t talk for fear they might cry. Then Mrs. Jeannette Muhlbach, the probation officer who was more like a friend after this morning’s drive from Los Angeles, took her hand and the three of them left the room.

As she went downstairs from the second floor courtroom, the reporters and photographers were waiting but the deputy sheriffs cleared a path for them. She hardly noticed the brief flashes from the camera light bulbs as they walked through.

She turned around for a last look back and saw the newspapermen making a circle around Daddy and his lawyers. Pop just shrugged and said to them: “I’m too upset to talk.” But Arthur Crowley, his attorney, interrupted, saying: “Of course Mr. Crane is very happy with the decision. It’s a great relief to both parents to have their daughter out of Juvenile Hall.”

Outside they walked through the crowds toward one of the cars waiting at the curb. The reporters caught up with Mommy just as she was about to step into a green limousine and she could hear them asking: “Would you like the girl returned to you?” Trying to smile cheerfully, Mommy answered: “Wouldn’t any mother? . . .”

Their limousine started and she leaned back against the smooth leather of the car, staring out at the people, the buildings and the cool Pacific water. How can I choose between Mummy and Daddy? she asked herself. I wonder what the court will decide.

In three weeks from now, Cheryl Crane will know.

—G. DIVAS

LANA TURNER STARS IN UNIVERSAL-INTERNATIONAL’S “IMITATION OF LIFE”

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE OCTOBER 1958