Love In The Shadow Of Fear—Rory Calhoun & Lita Baron

This is the love story of a rugged, virile, sentimental Irishman and a beautiful, sensitive, loyal woman. It is a story that could have happened anywhere in the world, against any background. The fact that it happened against the glitter and glamour of a show business has little to do with the story’s purport. If Rory Calhoun had remained a forestry-service employee and Lita Baron had married a fire fighter, their life together would not differ notably in the essentials from that they live today in Hollywood.

It all began in 1943 when Isabelita Castro, billed briefly as “Isabelita,” was singing with Xavier Cugat’s band, which was making one-night appearances in key cities along the California coast.

Word of this musical boon reached far into the lettuce towns, into the cattle country and filtered through the timbered fastnesses of mountain forests. News reached a lookout station where several men, living behind binoculars, served their country by scanning the horizons for tendrils of tragic smoke. One man told his relief, “You lucky cuss; this is your Saturday night off. Gosh, what I wouldn’t give to crack my sacroiliac in a rumba again. Lights, music, girls, Cugat’s band. D’ya know, Smoky, I’m having an awful time even remembering what girls look like.”

“I’ll take the duty if you want to go to town,” Smoky answered.

His partner brightened for a moment, then shook his head. “It wouldn’t be right,” he said righteously. “I took your day off last time.”

So Smoky went to San Jose and stood in the stag line rimming the Civic Auditorium.

He stood quietly, his eyes riveted on the girl singing with the band.

All evening he watched her and listened, but, not having earned a reputation for being a talkative type, he never spoke to her.

Back at the ranger station, he made his report. No, he said, he hadn’t danced with anyone. Honest! He had only listened to the music. But it was very good music.

“What a waste,” moaned his partner.

Months later, Rory Calhoun made a decision to spend his vacation in Hollywood, visiting his grandmother. While there, he met Alan Ladd on a bridle path, was signed by David O. Selznick and given his first screen role in “The Great John L.”

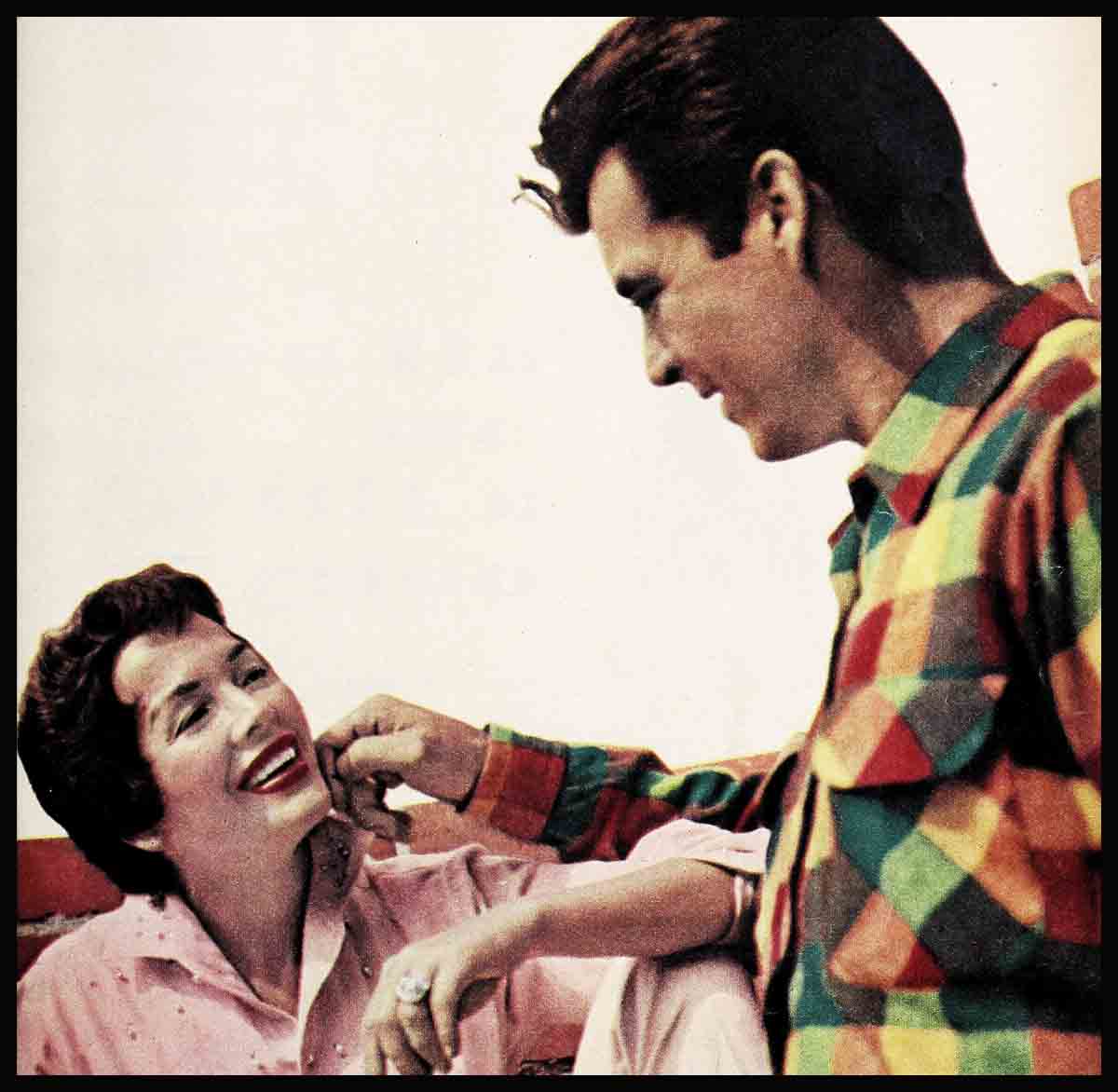

Meanwhile Isabelita had, by 1946, left Xavier Cugat and formed her own band. She spent most of 1947 on tour, but in 1948 she returned to Hollywood to open Don Loper’s opulent, but brief, night-club venture. That first night, Rory, together with his date and two other couples, was ringside. Thereafter, for eight weeks, Rory arrived every night.

From Loper’s, Isabelita’s band moved to Felix Young’s Pavillion for five weeks, then on to four weeks at Mocambo. Rory Calhoun followed her and became as un-obtrusive and inescapable as the amusement tax. But not until the Friday beginning the rumba band’s final week was something new added.

On that day, Rory picked up his pay check at the studio and realized that, because his parents had gone away for the weekend, he had to eat out.

Behind a choice cigar, he made his way to Mocambo where, for the first time in his life, he ordered a magnum of champagne to be iced for his table. When Isabelita passed his booth after having finished one of her dance sets, Rory rose, bowed and said gravely, “I would be honored if you would join me. I’m Rory Calhoun, and I’ve been a fan of yours since the days when you were singing with Xavier Cugat.”

Lita explained that she had a firm rule against joining patrons at their tables, no matter how much she might be inclined.

“Would you dance with me then?” he wanted to know. “This is my big night and it would mean a lot to me if you’d dance with me just once.”

There was a Baron rule against dancing with patrons, also going home with patrons. But Lita broke both rules that night.

“Quite a guy,” Joe Castro told his sister in approval when Rory brought her home.

Mrs. Castro said, “He could be Spanish, if you didn’t know he was Irish.” No greater praise could have been wrung from a lady born and still emotionally rooted in Andalusia.

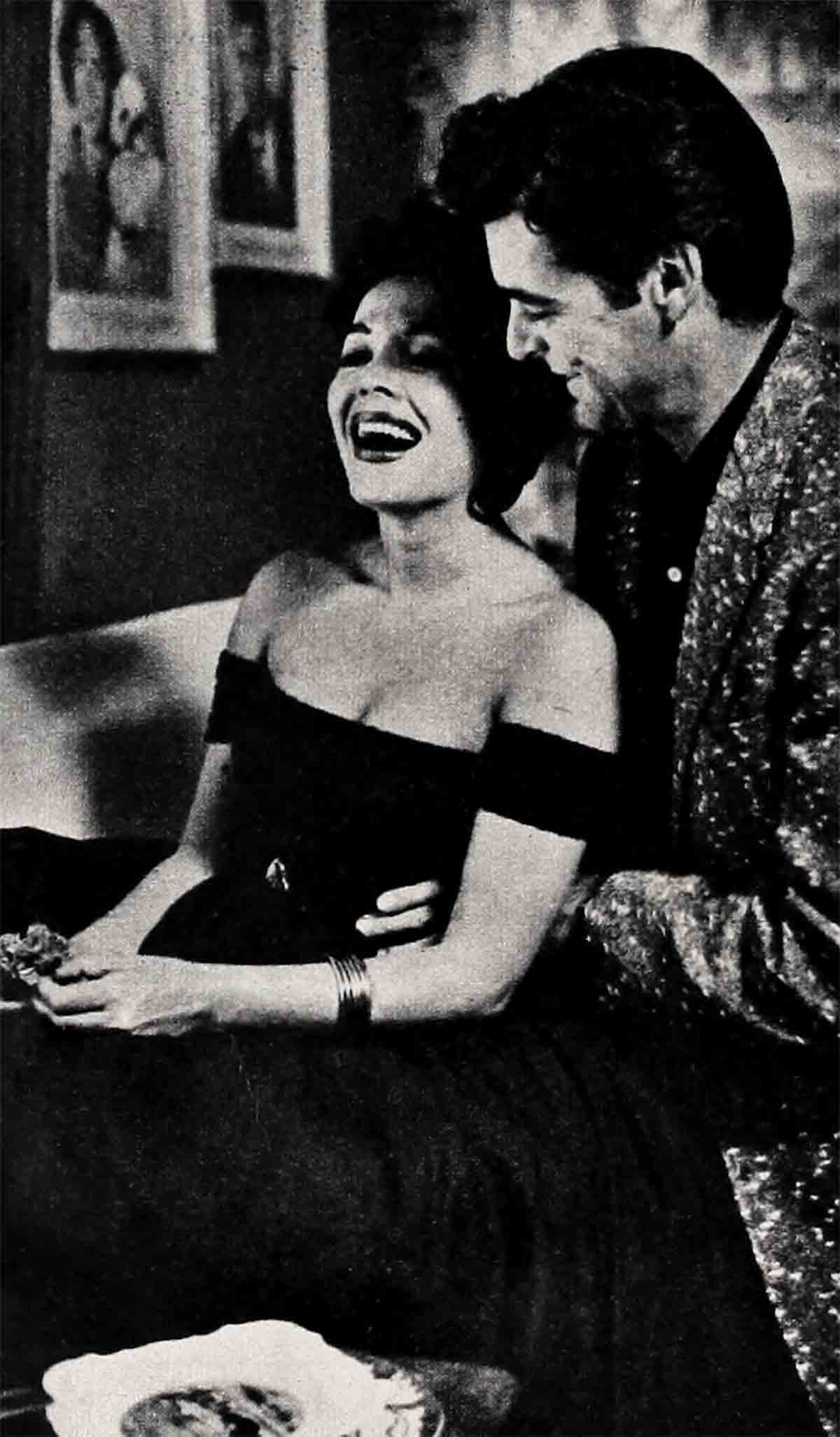

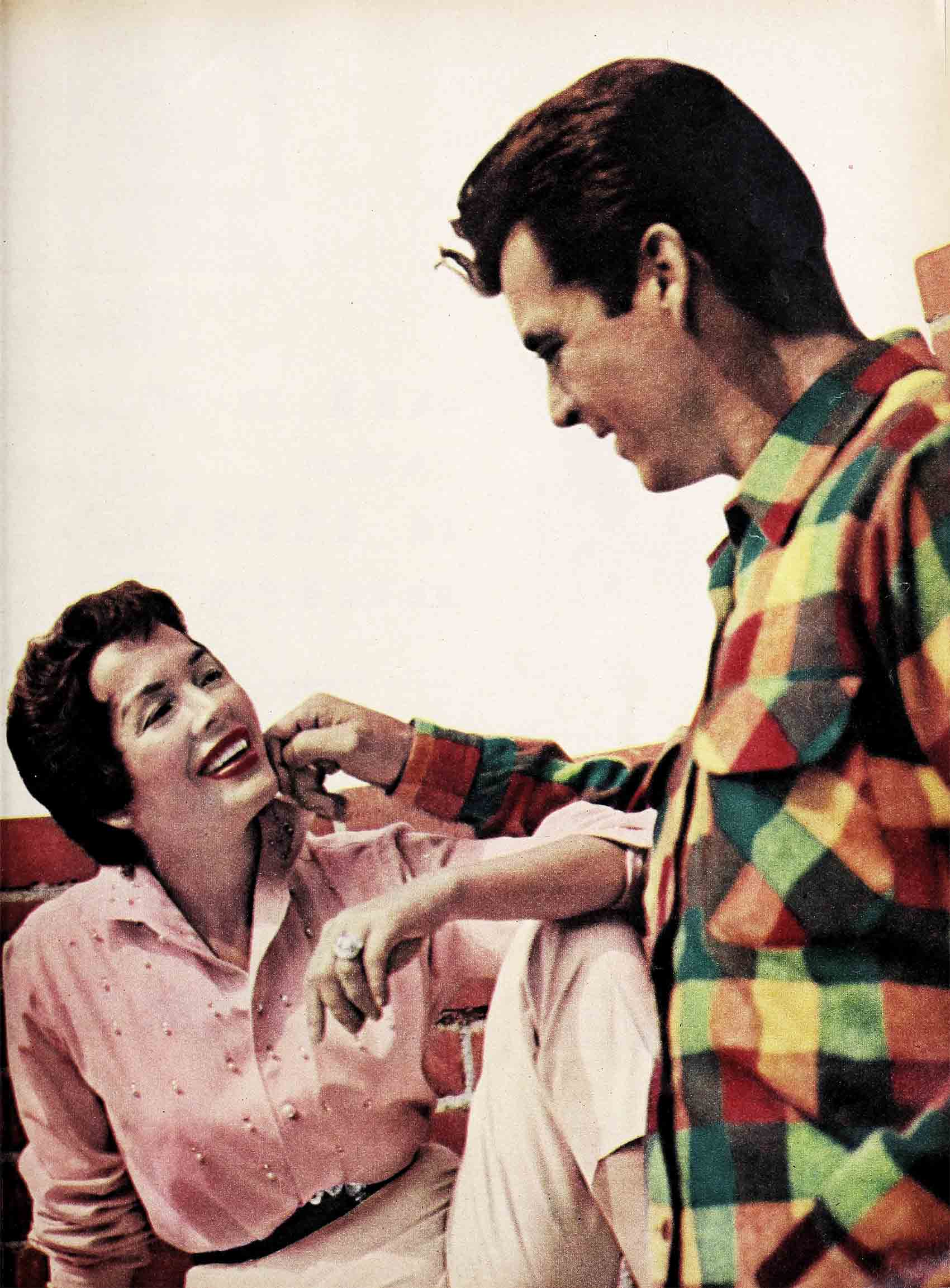

Rory called nearly every night while he was away and, when he returned, he and Lita were together evening after evening. They found thousands of things to talk about, hundreds to laugh about and here and there a topic fraught with sandpaper. For instance, the importance of keeping appointments on time.

Rory and Lita had made a dinner date. But because Lita had to stop at a modiste’s in the afternoon, it was understood that |she would meet Rory at Armstrong-Schroeder’s at six. Lita met a couple she knew in New Orleans. All three left for some conversation, and not until 6:30 did Lita notice the time.

Her friends volunteered to drive her anywhere, wound up by returning her to the modiste’s, where Lita had hoped to meet her sister. Her sister had gone, thinking Lita was evening-bound with her New Orleans friends. Said the modiste, “Rory Calhoun was here and was he mad! I’ve seldom seen such a furious man.”

“What did you tell him?” Lita demanded.

“What could I tell him! I said I had no idea where you were going when you left here, but that you had started somewhere with a Frenchman.”

Lita’s eyes sought the heavens. She then asked her friends to chauffeur her to the appointed restaurant and, once there, she spun to the secluded booth which had come to be their especially favored dinner-time hideaway.

Rory, convincingly disguised as a thundercloud, glowered in her direction and wanted to know if she had spent a pleasant afternoon with her French admirer.

Standing very straight, Lita said evenly, “Yes, I did. With him and his wife, my especial friend, people I have known for a long time and people whom you would have liked if you had waited around for a few minutes to meet them.

“When we have a date for six o’clock, I expect to be on time and I expect you to be on time,” quoth Mr. Calhoun.

Lita let him talk himself out, agreeing furiously with his condemnation of the tardy, the forgetful, the inconsiderate. Quite suddenly, meeting one another’s eyes, they began to laugh. “If all our arguments can only end this way—” said Rory.

There was no time for another quarrel because Rory left a week later for Durango (Lita has said, “During those days it seems to me that every time I told Rory goodbye he was on his way to Durango”). Same location, new picture: “Ticket to Tomahawk.”

One afternoon during Rory’s absence, a massive package was delivered to Lita. Very light. Very bulky. “I simply can’t imagine,” she said to her curious family.

“Open it,” an executive member of the family suggested.

Within the stacks of tissue and the miles of ribbon, there lay a silver fox cape, an opulent garment that all but swallowed petite Isabelita. Her brother spotted the initials embroidered in the lining.

“What does ‘I.C.C.’ stand for besides Interstate Commerce Commission,” he wanted to know.

“Isabelita Castro Calhoun, of course,” murmured Lita, hugging the foxes. “It’s Rory’s way of proposing, I think.”

“Pretty sure of himself,” grinned Joe.

“What’s wrong with that?” the about-to-be Mrs. Calhoun wanted to know.

“Nothing,” agreed the family in unison.

Much earlier Rory had told Lita, and afterward her family, about his boyhood wildness and what it had cost him. At first Lita had hesitated to believe his story, since Rory is a great deadpan kidder. But gradually, she was forced to accept as past truth a confession so far removed from the present Rory Calhoun that it seemed it must have happened to another person in another life.

When Rory returned from Durango, having gotten Lita’s yes through a series of long-distance telephone calls, he wanted to be married at once. On his own birthday, August 8, for instance or, at least, on Lita’s birthday, August 11. As things worked out, they were married in Santa Barbara at All Saints Episcopal Church at four-thirty on August 29, 1948.

Lita wore a pale gray wool jersey sheath over which spread a voluminous, but filmy, gray Chantilly lace skirt. Her Juliet cap was made of matching lace over gray jersey, embroidered with seed pearls. She carried white orchids, wore her mother’s erstwhile bridal blue garter and carried a penny in her shoe for luck.

Rory’s gift to Lita was a heavy gold link bracelet on which was hung a gold medallion. The center was a three-dimensional heart and engraved about the frame was the toast, “May we live as long as we love, and may we love as long as we live.”

Seven years later, on August 29, 1955 (Rory believes that the number seven is star-blessed), the Calhouns, having completed the necessary study, were remarried in a nuptial mass in the Catholic Church.

Lita, not changed seven minutes by the seven years, wore her wedding dress, but Rory, grown more muscular in shoulders and arms, had to have a new suit tailored.

Between these two wedding ceremonies, a marriage had been built. A marriage, like a cathedral, is only well started when the foundations have been outlined and the cornerstone set in place. The actual construction requires day by day work and prayer, laughter and mistakes, tears and triumphs and, above all, an ever-growing faith in and an overwhelming conviction of the power and the glory of the love that can exist between a man and a woman.

And the Calhouns had their differences, their adjustments. Not especially unique for a young husband was Rory’s first complaint. “What in the world are you going to do with all those clothes!” he wanted to know as Lita tried to hang her wardrobe in their ranch-house closets. She and Rory had moved at once to the Ojai ranch that Mrs. Castro had bought for them. The property was a sentimental treasure for Rory because it had once belonged to his grandfather and the happiest days of his boyhood had been spent there.

Lita explained that she owned only two hundred and fifty evening combinations and only about a hundred suits, and that no active entertainer could maintain appearances with much less. After all, she said, expanding her theme, she still had her outfits from a New Orleans engagement that extended for five months, one hundred and fifty days. Naturally she had needed a change per day because much of the patronage at The Roosevelt had been repeat business. Likewise, still in excellent condition were the gowns in which she had been photographed from time to time, which had to be put aside for a year or so before they could be worn again. Also, naturally, the total had been swelled by the wardrobe she had used at Don Loper’s, at Le Pavillion and at Mocambo.

Rory dropped the matter. But inevitably, there came an evening, a few months after the Calhouns were married, when they were invited to a small but elegant dinner party. Lita felt she lacked the perfect apparel, so she popped down to a specialty store and picked up a bargain cocktail suit for fifty-five dollars, an expenditure that almost sent her spouse through the roof. “With two closets so filled with clothes that you couldn’t hang a cobweb in there, you needed another outfit!”

Lita waited until the storm had subsided, then asked quietly, “How much did you pay for the rifle you bought today, dear?”

The Irishman ducked his head. “That’s different,” he said in a tone mainly distinguished by charming logic. “Every gun as a different purpose and a different scope. I love guns; they’re my hobby, you know that. I don’t gamble, I don’t lavish a fortune on cars the way some guys do. I collect guns and I make good use of them.”

“How much?” demanded his wife, not to be put off with forensics.

“Well, four hundred and fifty. But you don’t get a gun like that for peanuts. Just a minute until I show you how it’s balanced, how . . .”

“And you don’t get dresses like this one for peanuts. Note the fabric, the lines, the detailing.”

Rory began to grin, so Lita made a deal. “Every time you buy a gun, I’m entitled to buy a dress. Is that a deal?”

“A deal. Only, where are you going to hang this new dress?”

Lita ignored the question as any wise wife should.

Senor Calhoun tried to pull a cutie. The next time he bought a gun for himself, he also bought one for Lita.

“Thank you very much,” she said. “I’ll go shopping for my dress in a day or two.”

Her husband suppressed a grin. “Okay, if you’re going to be literal about these things.”

“Literal and well-dressed,” was the airy reply.

There were other squabbles to be re-called with laughter. One night Rory and Joe, Lita’s brother, had to make a business trip to Ojai. They were to be gone an hour. They still don’t know how it happened except that someone wanted to buy them a beer, after which they bought a beer, then drove to another ranch to see a new Hereford bull recently imported from Texas and on the way home they had a flat tire. Considering one thing or ten, they failed to reach home until nearly midnight, and that is late on a ranch.

Lita had waited up. As the miscreants shuffled into the house, she leapt from her chair like a popped champagne cork and began to froth—at Joe. She said she was amazed that a brother of hers would promise to return in an hour and then fail to show for five, worrying a person into fits. She added that they hadn’t been brought up to be so inconsiderate; after all, the telephone was a great little invention and what was he thinking of anyhow, keeping Rory out until all hours when he had to drive to the studio the next day? She announced she didn’t want to hear any stupid explanations because there could be no excuse.

By the time she got around to Rory, she couldn’t find him. Wily Calhoun, at the first explosion, strategically withdrew from the scene of carnage and was fast asleep when Lita entered the bedroom forty sentences later. He was, as a matter of fact, snoring. Today, Rory considers this one of his most convincing scenes.

For Lita, having grown up in the entertainment business, in which the civilized hours are from noon until 2 A.M. and the most notable pelt was a well-styled mink, getting used to the wide open spaces, opening wide at dawn and accepting areas peopled by furs on four legs was a quaking operation.

Valiantly she accompanied Rory, Guy Madison and the Howard Hills on bow and arrow expeditions, expecting momenitarily to serve as hors d’oeuvres for an enterprising cougar.

One morning, after other members of the party had left with daybreak trickling through the pines and she had hit the sack for some more rest in the reassuring brightness of day, Lita was awakened by a mighty swooping through the camp that came past her incredulous ears and horrified eyes. Buzzards, attracted by the game killed the previous day, had invaded the camp and were casing the only un-refrigerated morsel they could spot.

According to the other hunters, Lita’s screams could have been heard in New York harbor above the blast of an out-going liner. In any case, everyone came running, and Lita’s nerves were calmed by an afternoon of fishing.

Lita still has trouble riding horseback. Rory says she looks like a jockey closing ground toward the wire. The truth is that she should ride sidesaddle or a Shetland pony because of her childlike stature. Even so, she has never been thrown.

When two professional people marry there always arises the question as to which career shall be dominant. Early in the marriage, Lita felt certain that she had an answer: her career was merely going to be altered. She discovered that she was to become a mother. Rory, upon hearing the news, rushed out and bought a new medallion for Lita’s bracelet—a cherub with curly head, chubby arms and legs on one side. However, at the end of four months, the stork canceled his appointment.

This was a tragic experience to accept. Rory has always wanted children. He and Lita had talked about parenthood, had dreamed of it, had agreed upon its responsibilities and its delights, its dangers and its rich rewards.

For days after, Lita could not control her tears. The final flood was shed when Rory brought her a new medallion for her bracelet: a sacred medal of Our Lady of Perpetual Sorrows. In essence, he said that their disappointment, compared to the classic griefs of time, was not so great. They were young; they must place their trust in the future.

Even when the second child, planned for, joyously anticipated, desperately wanted in a world in which not every child is so welcome, was taken from them, they maintained their confidence. They would wait and pray.

Meanwhile it seemed sensible for Lita to continue with her career. She had many offers for picture work and for night-club engagements. Some she accepted. Yet every time a really juicy opportunity was presented, it could be accepted only on the basis of being away from Rory. No matter how carefully they planned, they could not seem to make arrangements which would give Rory time to finish a picture, go on tour with Lita without studio worry and return on schedule for a new film assignment.

When Lita appeared in Las Vegas, dancing with Billy Daniel, Rory was available during the rehearsal period. (He once made a round trip, over 600 miles, Las Vegas to Los Angeles and return, in slightly more than twelve hours of driving in order to fetch a gown being completed for Lita’s premiere.) But when Lita was working at Mocambo, Rory was on location for “Four Guns to the Border.” And he was unable to join her for her St. Regis opening in New York, although he arrived later in the week. When Rory was sent to South America for “Way of a Gaucho,” Lita was rehearsing for a nightclub act and couldn’t go along. For the first time, Rory abandoned his old friend the telephone, and actually wrote. Lita saved every letter, knowing how precious a love missive is in these days of cards, telegrams and cables.

In one of the letters he wrote, “I’ve shot a few crocodiles for you. For me, too. I thought we could have shoes made of the skins and, one of these days, I’m going to have a croc saddle. Might even have me a croc Stetson if Madison wouldn’t give me such a bad time over it. I don’t think I could get away with saying he was only jealous. I’m bringing him a belt and billfold.

“We sure have to come down here on vacation someday. You’d love it, and the people would love you. The life is leisurely and the physical beauty of the country is breath-taking. Their pampas are like the plains of Kansas and their cities are something an artist has drawn. Buenos Aires’ boulevards and the shops that line them are equal—everybody says—to Paris. Man, those crazy mosaic sidewalks.

“We have so much to do that I swear I don’t see how we’re going to get around to it. Someday I want to take you to a restaurant outside of Atlanta called ‘Aunt Fanny’s Cabin.’ The colored boys sing the menu, and one of the specialties of the house is a potato cooked in boiling rosin. What a taste sensation.

“Another great place is the Purefoy Hotel in Taladega, Alabama, where they serve about thirty-two courses, family style. Love that South. While we’re down there we’ll have to stop in New Orleans for dinner at—where else—Antoine’s, and an alligator hunt with good old Charlie Cure.

“If all this sounds like I’m hungry, I have to admit that’s right, but not so much for food as for the sight and the sound and the touch of you.”

Lita made her decision to retire long before she made her statement. When her agent called one afternoon with one of the best offers she had ever received, she turned down the opportunity. “As far as I am concerned,” she said, “time spent away from Rory is time wasted from my life.”

Happily and without a backward glance, she had exchanged one career for another: actress-musician became wife extraordinary. The plan has paid off in many ways: One of them was Lita’s going along with Rory to Mexico when he starred in “Treasure of Pancho Villa,” largely shot in Cuernavaca, and then vacationing in glorious Acapulco.

But sometimes there were separations between Rory and Lita that could not be helped. Separations that were almost un-endurably sinister because of the import of the errands that took Rory away. Occasionally, someone who had known Rory during his headlong youth, would get word to him that a private meeting would be a good idea. Rory never told Lita when he was to see one of these get-rich-quick specialists, but somehow she always knew.

The approach was always the same general pitch: The character had known Rory when. . . . It would be a shame for the story to hit the newspapers, he would imply. How much would silence be worth to him?

Rory’s answer was always the same. His wife, his family, his closest friends, his studio advisers knew of his young mistakes, he would say. Sooner or later, the general public would know, so now was as good a time as any. He would not pay a bribe.

Lita, never the crying type, would wait for her husband to return, crying softly and praying. Better than anyone on earth, she knew how great the heartache he carried and the stamina that had gone into his flawless new life. Her early love, the young, unperceptive girl’s love, had deepened to fill a woman’s soul, and with it had grown an intellectual appreciation and respect for her man’s courage and his proud conviction.

Not long ago Lita received an intriguing fan letter, brief and to the point. “What is it like, being married to Rory Calhoun?” the writer asked.

Lita hasn’t answered it yet, but when she does, she thinks she will say, “It can be hectic. Rory taught me to drive a car, and the sentence I remember most clearly from the lessons is Rory’s exasperated observation, ‘You aren’t paying attention to what I’m telling you; driving a car is a very simple operation if you will just use your head.’ Of course, I was never a good driver until the gear-shifting bit was licked by engineers, and all I had to master was the technique of the brake and the choke.”

She also wants to say, “It can be funny—and reassuring. There is one columnist in town who likes to announce marital separations. Whenever Rory sees her he begins to repeat, clearly and with conviction, ‘I love my wife. We are not getting a divorce. We have not had an argument. We are not getting a divorce. I love my wife. We are not getting a divorce.’ As a result I seldom get the is-there-a-rift-call which troubles so many picture-business wives.”

But most of all, she wants to say, “It can be a sentimental journey.” And she would like to tell the story of their fifth wedding anniversary. They had been invited to a sumptuous dinner party; Lita was wearing a new gown and Rory was wearing a new tuxedo. However, he—the most aware of men—had said nothing about the anniversary, had presented neither a card nor gift—not even a very small remembrance.

When Lita emerged from her dressing room, she found Rory sitting in a chair in the hallway, his eyes covered by interlaced hands. Alarmed, she wanted to know what was wrong. “It hit me just a few minutes ago,” he explained. “One of the worst headaches I’ve ever had. Would you mind getting me an aspirin from the bathroom and a glass of water? No, not from your bathroom. From mine. I have a new bottle of pain-reliever that is supposed to be powerful.”

Scorching into the bathroom, Lita caught sight of a big, beribboned and bowed box standing in the bathtub. In spite of herself she caught her breath, and Rory’s abrupt chuckle from the hallway assured her that he had staged a spontaneous recovery.

Within the box was a cerulean silverblue mink stole—and a card. The card said many things. But all combined they spelled out one important declaration that is forever deathless: “Lita, I love you—Rory.”

THE END

—BY FREDDA DUDLEY BALLING

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE OCTOBER 1955