Richard Burton—The Welsh Rare Bit

Richard Burton, looking as unlike a Hollywood star as possible in baggy corduroys, a well-worn tweed jacket and with bits of grease paint still clinging to his forehead, put down the newspaper clipping with a sigh and turned to the man behind the well-worn oak bar in the murky London pub.

“Another pint of mild-and-bitter, please,” he said, and then, picking up the dog-eared bit of paper, turned to his companion.

“How do you like this?” he said, and in an exaggeration of the majestic Shakespearean tones that were thrilling patrons of the Old Vic Theatre nightly (and at matinees on Thursdays and Saturdays) he read the gossip of a London society writer:

Richard Burton has been titillating his English friends at all the fashionable soirees in the better drawing rooms of London with his hilarious accounts of the fantastic life in Hollywood.

Burton glanced around the drab, smoky interior of The Olive Branch, a nondescript public house in a squalid part of London. A pub as far removed in appearance as in distance from the glamour and bright lights of the West End night clubs usually frequented by visiting Hollywood stars. A pub whose “regulars” are, for the most part, dock workers, railway hands (it’s a stone’s throw from Waterloo Station) and neighborhood folk, with a smattering of the players from the famous Old Vic, directly across the street.

“Well, friends,” he called, “if this is a fashionable London soiree, I’d better set ’em up. One all around, Joe. And then—back to rehearsal.”

Small wonder that Burton was amused at the report. It was either that or become very, very angry—and typical of his wry sense of humor, he chose to laugh.

“What chance have I had to attend any soirees, fashionable or otherwise?” he grinned, as he downed his pint of beer. “Since I arrived back in England last July I’ve spent every day from 10:30 in the morning until past midnight at the theatre, rehearsing next week’s play while appearing in the current one. And, in case you think I’m complaining of overwork, I’ve loved every minute of it.”

The item in question, nevertheless, was only one of many that have served to build up a false picture of Richard Burton, and the time seems ripe to debunk the legend of Burton the debunker, Burton the stingy, Burton the indifferent, Burton the flirt. Rich is the first to admit he has his faults. But he can’t quite go along with the gang that he’s as bad as some of the stories have pictured him, if for no other reason than the simplicity and honesty of his approach to life.

It probably all goes back to his boyhood in the bleak, treeless valley in South Wales in the tiny mining village of Pontrhydyfen, where he was born. There were thirteen in his family and his name was Richard Jenkins then. His father and six brothers were all miners and Richard readily admits they lived in a slum neighborhood. Work, work, and more work was the order of the day, but when each day’s work was over, those Welsh miners who were Burton’s grandfather, father and brothers relaxed in the only way they knew—by playing just as hard as they had toiled in the pits. And always with a laugh and a melodious Welsh voice raised in song to forget the rigors of the day.

“When I was a kid,” Rich recalls, “whenever I ran into difficulties, and there were plenty of them in the town where we lived, the only answer seemed to be to work harder—and to laugh while we were doing it. Then, too, we’re a very knowledgeable family about the Bible and likely to quote reams of it on all possible occasions. The combination of the two can’t be beat. The one passage that has probably been the greatest influence in my life is the one from Ecclesiastes that goes:

“ ‘Whatsoever thy hand findeth to do, do it with thy might; for there is no work, nor device, nor knowledge, nor wisdom, in the grave, wither thou goest.’

“Father used to throw this at me when I refused to cut the sticks to make the fire. I can’t remember when I didn’t know it and I carry it always with me engraved on a tag on my key ring. I’ve always behaved the same, when I was eight and eighteen and now at twenty-eight. What I do, I do with all my might, and I’m only sorry if my enthusiasm is often misunderstood.” As it obviously was by the reporter who wrote of Burton’s titillating accounts of life in Hollywood.

Rich might have grown up and gone into the mines like his father and brothers if it were not for a wonderful teacher named Philip Burton who taught Rich in high school. Philip Burton got Rich interested in acting, taught him how to speak English without a Welsh accent and helped promote his scholarship to Oxford. He even paid for his clothes while he was at the University. Today, Rich calls him “my second father” and took his name when he became a professional actor.

Since Rich was only sixteen when he won his scholarship, he could not enter Oxford for a year. During this interim, he answered a newspaper advertisement of Emlyn Williams, famed author of The Corn Is Green, who wanted someone who could speak Welsh and looked twenty-two. Sixteen-year-old Mr. Richard Jenkins went up for a reading before Williams and came out with a role in “The Druid’s Rest.” The play ran for a year, just long enough to permit Rich to enter Oxford right on schedule.

With the war on, Richard joined the Royal Air Force after his first year at Oxford and was sent to Canada to train as a navigator. At the end of the war, with eight cents in his pocket, he went to New York. While there, he sang Welsh songs for his supper, did his sleeping in the subways and on the post office steps. When he finally returned to London, his luck changed and he found immediate stardom.

Richard Burton’s American film career began in 1952 when Daphne DuMaurier herself requested him for the lead in “My Cousin Rachel.” Recently he finished his fourth picture for 20th, “Prince of Players.”

While Rich knew adversity as a youngster, his stage success was not the result of years of discouragement. And just as he was taught to laugh at adversity when he was a youngster, so today, Rich prefers not to be serious when he can be otherwise. His capacity for humor is as great as his capacity for work.

“Sure I’ve told a few friends some amusing experiences I had in Hollywood,” he grins, “but aside from not attending any fashionable soirees, I’m not even sure what ‘titillate’ means.”

It wasn’t the first time Rich found himself misquoted, thanks to this lack of seriousness. When reporters who met his plane asked the obvious question, “What do you think of Hollywood?” Rich, his face perfectly straight, delivered his reply in the best possible “bop” language. “Hollywood,” he deadpanned, “is a real crazy town; the people there are real nervous.” As anyone familiar with bop jargon knows, Rich was only being complimentary. Or thought he was, until he picked up next morning’s paper. “Richard Burton,” columned one of London’s leading columnists, “says Hollywood is insane, and that everyone connected with the motion-picture industry is extremely nervous.”

Now take those stories you’ve undoubtedly read about Burton being stingy. About his indifference to clothes, his living with friends to escape hotel bills, his failure to show up regularly at Ciro’s and Mocambo. Richard will readily admit that he does count his pennies. He’s done it all his life. He knows how much he has coming in each month, and despite what has been printed about his financial “take,” his contractual obligations, his income taxes leave him with far less than the fabulous salary reported in the papers. He will also tell you that when he and his wife first arrived in Hollywood they moved into a $750 a month apartment engaged for them by some British friends. Their car was a Cadillac at another $350 per month. Their restaurant bills at all the suggested places ran into a phenomenal figure. Pretty soon the Burtons found, even as you and I, that they were spending far more than they were earning. So they began to cut down. Back went the Cadillac; instead the Burtons began driving a Ford. A modest apartment replaced the glamorous penthouse. A quiet, unpublicized restaurant was found instead of expensive Romanoff’s or La Rue. Out of this, the myth that Richard Burton was stingy.

Yet when an English girl, a former technician in one of the British studios, fell ill during her vacation in Hollywood, only one member of the British colony, most of whom knew her well, found his way to her bedside. Richard Burton.

Maybe he heard his dad saying, “Whatsoever thy hand findeth to do, do it with thy might.” Maybe he didn’t. At any rate, it was only Richard Burton who went to see her in the hospital, and it was only Richard Burton who said:

“Look, sweetie. I know it’s tough to get money out of England these days. Don’t worry about what all this will cost. You just concentrate on getting well.”

And with that, although he could ill afford it, he quietly slipped an endorsed check into her hand—the amount left blank.

When his business manager broke her neck in an automobile accident, Rich was completely at her service. And it was more than monetary aid. Realizing the desperateness of her situation, he sat day after day in her darkened room, gently holding her hand and softly reciting comforting passages from the Bible.

Those words must have reached into her subconscious mind, yet she recalls it was a laugh at Burton’s expense that brought her back to normalcy. Her nurse approached her one morning with a message from a director’s wife who was a patient in the next room. “I don’t know who your friend is who recites from the Bible,” was the message, “but whoever he is, he should certainly try Shakespeare.”

Burton is the first to admit that he has a dreadful memory for names, and suggests that this may be the reason he has been branded conceited and arrogant.

“Maybe it’s because I’m concentrating too hard on remembering my parts (I’m playing five, alternately, at the Old Vic), but I simply draw a blank when it comes to recalling names. Do you know, I once forgot my wife’s name? I started to introduce her, and for the life of me I couldn’t think of it. In desperation, I presented her as Phyllis, and her name is Sybil! Brother, if looks could kill, I wouldn’t be telling this now.”

“And then there was the afternoon,” he continued, “when the doorman at the theatre informed me there was a Mr. Aherne to see me. ‘Mr. Aherne?’ I said. ‘I don’t know any Mr. Aherne.’ ‘The gentleman is quite insistent,’ the doorman went on. I was just as insistent that I didn’t know who Mr. Aherne was, but I was finally persuaded to go to the stage entrance. There was my greatest buddy from my RAF days. A hearty Irishman I’d merely shared room and plane with for four years!”

You may also have read that Richard Burton does not grant interviews. In a sense that’s true. He does not“grant” them. As Burton says, “Grant is a pretty lordly term for a simple Welshman like myself. I’m grateful when a newspaper person wants to interview me. But I guess I must learn to stop saying exactly what I think, for I’ve found that can get me in nothing but trouble.”

Like the woman from the small Middle Western paper who was one of many to interview Burton during the filming of “The Robe.”

“She asked all the routine questions,” Rich recalls, “including the inevitable one about, ‘What are you afraid of?’ Well, I can honestly say I’m not afraid of anything. Not afraid, at least, to the point where I won’t tackle it and at least have a try. That’s exactly what I told her,-and added, ‘I’m just a little apprehensive of death. Imagine my surprise when the studio publicity man showed me the clipping a couple of weeks later. There, i bold black type, was the headline: ‘Richard Burton Fears Death.’

Burton’s driving ambition, sparked, no doubt, by that same Biblical passage, has led to further misquotations. Asked what his aim in life is, Richard replied: “To be the best in my field. I hope to be the finest actor under thirty-five on the stage or screen.” So out came the reporter, unused, no doubt, to such disarming frankness, saying, “Richard Burton says he’s the finest actor on the stage or screen.”

Burton is quite sure if he ever does have any delusions of grandeur, all he need do is visit his eighty-two-year-old father in Wales. Dad, in fact, has difficulty in remembering which of his seven sons is which, and often gets Richard confused with his brother Will, who went to sea. When Rich visited his family before starting his stint at the Old Vic, his father asked where he had been.

“In Hollywood, Dad,” was Burton’s reply. There was a long pause. “I knew,” was father’s only comment, in broad, rolling Welsh, “you should never have gone off on that sailing ship.”

The writer who said that Richard Burton was disdainful of his fans should stand outside the Old Vic some evening in the chilly London dusk. British Shakespearean fans are much the same as American movie fans, differing, perhaps, in only one respect. They are much more likely to stand quietly in line waiting their turn for autographs rather than push and shove in an attempt to be first to obtain the coveted signature. When Rich emerges, there is an excited hum of conversation, and not only does he sign the bits of paper, he is genuinely interested in the comments offered by these people who are, for the most part, ardent students of the Bard who are eager to offer their opinion. Burton accepts their comments very seriously and admits that a “Better than Barrymore, old boy,” from a grizzled first-nighter at “Hamlet” gave him more of a lift than any of the glowing reports in next day’s papers.

After the opening of “Coriolanus,” an indignant elderly fan cornered Burton at the stage door to berate him soundly for failing to take a curtain call.

“Just because you been to ’ollywood, lad, is no cause for you to be big-headed,” said the man. “Why weren’t you out there taking a bow with the rest of ’em? You mayn’t have been the star, but you might have given us a smile and a bow.”

“It took three pints of beer at The Olive Branch,” Rich laughs, “before I could convince my newfound friend that my absence from the final curtain was unavoidable. You see, my last scene called for me to take a fall, and I fell so hard that I ended up with a violent nose bleed. Guess that’s one time I shouldn’t have ‘done it with my might.’ ”

Burton personally answers almost every fan letter he receives. The almost is his one reservation. He refuses to reply to gushing nonsensities of adolescent, hero-worshipping girls who, he feels, should not be encouraged. But, if their letters are critical or complimentary about his acting every comment not only is answered but appreciated.

Of all the accusations that have been made against him, Burton confesses that one is perfectly true. He is a flirt.

“I adore women in general,” he explains with disarming honesty, “and I like being in their company. The prettiest girl at a party is the one I want to sit next to or dance with, so in order to make sure I get the chance, I always say the nicest possible things because I know it will please her.”

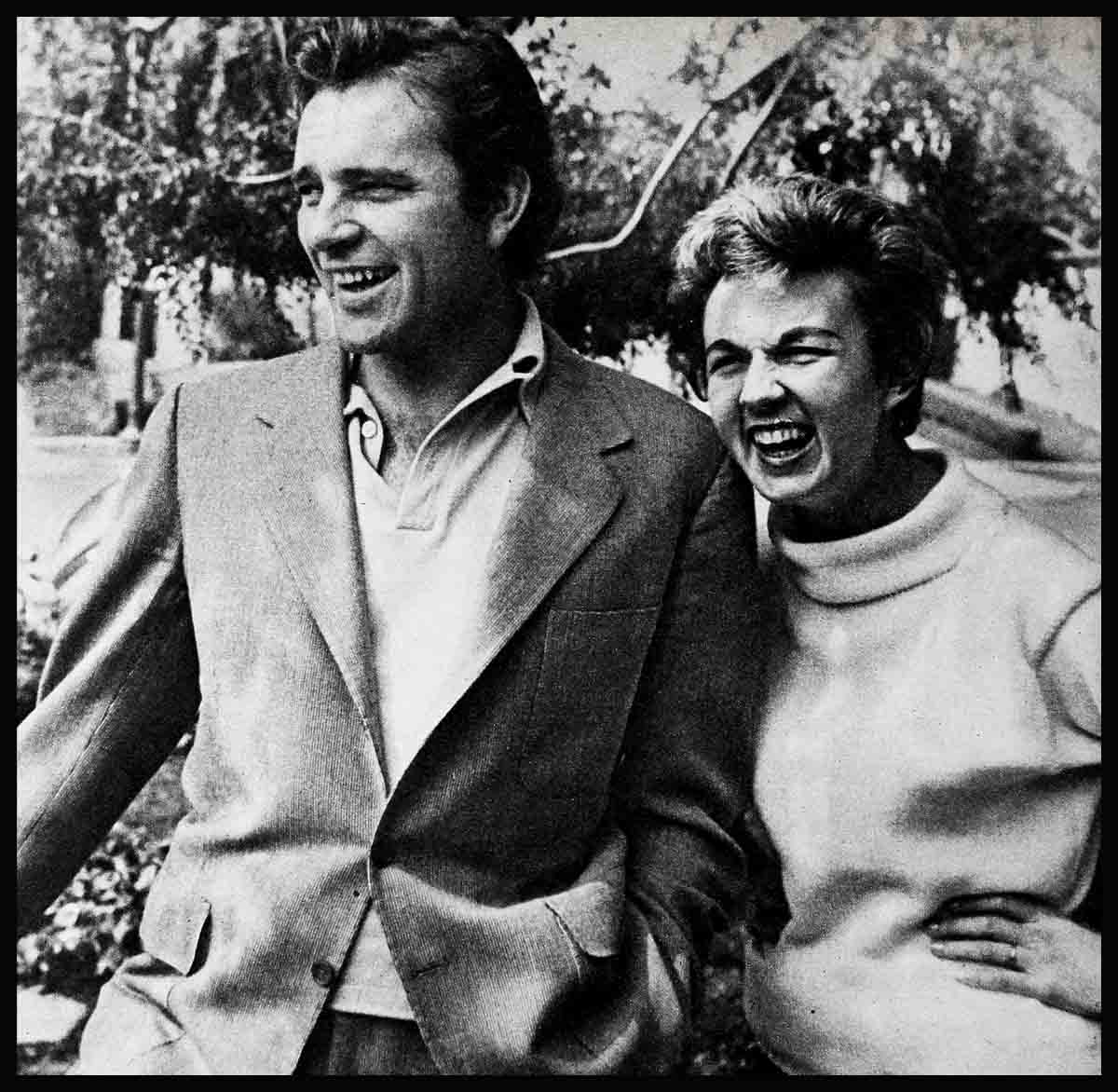

And what does Mrs. Burton, who was an actress herself and met Rich when he was a star and she an eighteen-year-old bit player in Williams’ “The Last Days of Dolwyn,” think of the fact that her husband, whether because of his unabashed approach of unmasked flattery, his quick wit, his seemingly endless fund of Welsh songs and stories, or just his completely masculine attractiveness, is usually the center of all feminine eyes? Sybil Burton is philosophic about it all.

“I’ve watched Rich be just as charming to a seven-year-old child or an eighty-year-old woman as he is to the reigning beauty of London or Hollywood,” she smiles. “And as long as he keeps it that way, it’s all right with me. After all, I’m Welsh, too, and was brought up on the same motto: ‘Whatsoever thy hand findeth to do, do it with thy might.’ So I guess I can’t complain that Rich flirts with young and old with the same intensity that he puts into everything else he tackles—that is, if he continues to keep it that way!”

THE END

—BY MARTHA BUCKLEY

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE MAY 1955