We Saved Our Marriage—Donald O’Connor & Gwen Carter

My wife Gwen and I celebrated our sixth wedding anniversary 6000 miles apart. I was in Berlin, entertaining occupation troops in connection with the premiere of my new picture, “Francis,” and Gwen was keeping the home fires burning in Hollywood.

Gwen had wanted desperately to make the trip with me, and I wanted her to go, but we had decided that it would be unfair to our three-and-a-half-year-old daughter, Donna, to risk both of her parents’ necks at once in an eighteen-day, winter-weather 18,000 mile flying junket which could be dangerous.

That was something relatively new for us, figuring out a problem in terms bigger than our own selfish wishes, and probably had something to do with the fact that we felt surer of one another, and were more deeply committed to our marriage on this anniversary than on any of the five which preceded it.

It’s no secret that Gwen and I have had difficulties in our marriage. When you work in the picture business, you can’t have even a minor tiff with your wife without stirring up a hornet’s nest of gossip, and more than once we have set the typewriters clicking with sad songs of another “unstable Hollywood marriage.” And more than once we have almost proved the sorrowful singers right.

Two years ago, Gwen and I separated for two days, ready to call it quits. But we found out something in those two days apart; we found out we loved one another enough to change the little things. Going on together meant giving up some things we had thought were important, but nothing half so important as our marriage.

Willingness to change, or should I say grow, is the greatest marriage insurance in the world, we think, and for couples who marry while they’re still in their teens, we’re convinced it is indispensable.

Teen-Agers can marry and live happily ever after, more happily, maybe, than anybody else. We still think young marriages are best if . . . if the young people in love know there will be special problems, and are ready to face them.

Like so many other young couples caught up in the frenzy of war time, the only problems which concerned Gwen and I were that we were going to be separated, and that I might go overseas, and anything might happen.

Of the more dangerous pitfalls, the kind which confront all very young marrieds, we were blissfully ignorant. We had to smarten up the hard way, but let me tell the whole story.

A friend of mine introduced me to Gwen Carter, first, at Ken Murray’s “Blackouts.” A few days later, I met her again at a drugstore counter on a sunny September afternoon in 1943. I knew very few girls my own age and no girls as pretty as Gwen. So I got right down to business by demanding her telephone number. The way Gwen looked at me, I knew I had made a bloop.

“The guy sitting next to her was her boy friend,” my friend told me later. “He’s captain of the football team at the school she goes to,’ she warned me further. And then she gave me Gwen’s number.

Gwen agreed to go out with me, I don’t know why, really. I felt awkward with Gwen’s friends, felt I didn’t know the lingo, the jive. But Gwen didn’t feel awkward with my set. She had a burning ambition to be an actress herself, and was fascinated with my work, and with the people she met in show business.

I made one terrible mistake, from the standpoint of our ultimately making a happy life together, right from the beginning. I was ridiculously possessive about Gwen, and jealous! If another man so much as looked at her twice, or asked her to dance, I’d sulk all evening.

I should have been proud that my friends found Gwen attractive, but I wasn’t that smart. I needed to grow up, but that was to come later, the hard way. Now I know that loving is not possessing, it is giving. Jealousy is pretty insulting, really, it indicates a lack of trust in the person you say you adore.

But I didn’t know that when I met Gwen. When I found myself falling in love, my one drive was to keep this wonderfully exciting, beautiful new thing all to myself. If I could keep it all to myself, build a wall around Gwen to keep away all my competitors, I thought Id have nothing to worry about.

I’m lucky that she liked me, and was interested in my work. Not only did she forgive me for not fitting into her gang; she liked me because I was “different.” I think she may even have been flattered by my jealousy, at first.

By apparently mutual consent we began “going steady.” We might have been going steady yet, if it hadn’t been for the war. I had been in volunteer flight training for some time, had my pilot’s license and 500 flying hours. I was a cinch to be hustled into the air corps, we figured, the minute I turned eighteen.

So our dates had a certain urgency. We had a lot of laughs to laugh, a lot of living to do, and not much time to do it.

“Promise me you’ll marry me soon,” I said one evening.

“Yes,” she said.

“Maybe in three months,” I said, “when I finish basic training, and get my first furlough.”

“Maybe,” she said.

We left it at that until one night just a few days before I was to be inducted. We went to a farewell party at Peggy Ryan’s. I told our good friends there that I hoped Gwen would marry me on my first furlough, that would be in three months.

“How do you know it will be in three months?” somebody said, and Peggy volunteered the cheerful news that her brother had waited for his furlough for a year.

Gwen cried on my shoulder on the way home in the car that night.

“I might never see you again,” “You might be killed.”

We kept right on driving, until we got to Las Vegas, and when we came home we were Mr. and Mrs. Donald O’Connor.

For the two days of our honeymoon, marriage was the kind of roseate dream you read about in the love story magazines.

And then Mrs. O’Connor went back to school, and Mr. O’Connor went to camp.

There followed the worst five months in this man’s life. Adjusting to a private’s routine after you’ve been a movie star is a rugged deal. And I was miserably lonely, and tortured with jealous fears.

Gwen’s graduation was nicely timed with my first furlough (I got one, after all!) and I convinced her that she should come back with me. I was still thinking of Old Number One, for there are better deals for girls than the life of a camp follower.

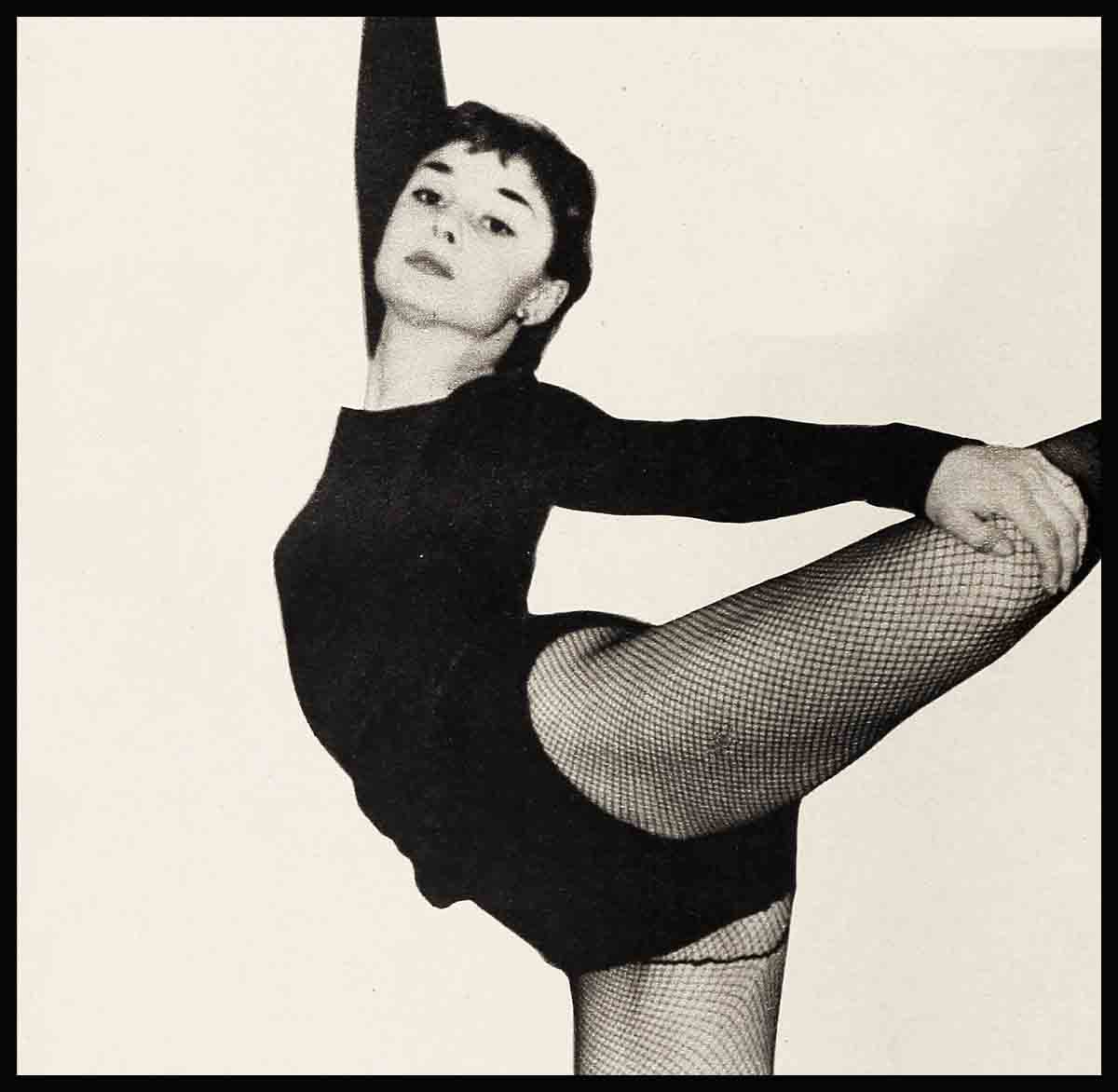

But we were lucky again. The army assigned me to special duty, producing and appearing in entertainments for the troops. I was lucky because I could do the sort of thing I do best and still serve my country, and Gwen was lucky because this new turn of events gave her her first chance to be an actress.

Gwen is bright and enthusiastic, and she likes to work. These qualities add up to a good actress, which it was clear, very soon, she was going to be.

To me, working with Gwen was great because it meant we could be together. But to Gwen it was something more, a chance to act—something which I, in my own life, had taken too long for granted. The work we love, like the people we love, are part of our life fulfillment.

When I was released from the army, I went on with the work I loved. Gwen came home to a life which, after the excitement of trooping days, was dull and empty.

It was the same homecoming, but it meant quite different things to the two of us. I was not completely unaware of the problem this imposed, of the strain it threatened for our marriage.

I spoke to the executives at Universal-International about a chance for Gwen in pictures, possibly as my leading lady. But they felt that it would be unwise to exploit the fact that their “adolescent” star was a married man.

So I worked, and Gwen waited, filling up her days those first few months in decorating and furnishing the new little house we had bought in the Valley.

When I went on a personal appearance tour after the release of my first picture, Gwen went along and worked with me in some of the same sketches we had done together during the war. It was exhilarating; we both love getting about the country meeting new people. The interval of our tour wiped out all the frustration Gwen had felt in the preceding months.

But back at home again, it was work and fulfillment, for me, in a long series of pictures, and just frustration for Gwen.

Night after night, I would come home tired from the studio, eat dinner in silence, and then fall asleep by the fire. I could at least have shared my experiences.

That sleeping gimmick of mine is another problem. When I get sleepy, I have to go to sleep, wherever I am. It used to drive Gwen crazy. We’d dress up and go out to a friend’s for dinner. Gwen had been alone all day and was eager to go out. I’d yawn through dinner and then go to sleep. In my politer moments, I’d go out to the car and go to sleep. But in any case, I’d abandon Gwen, who by this time had said, “I don’t dance, except with Donald” to so many guys that it had become a habit.

I can see now how boring this all must have been for Gwen, a beautiful girl, still in her teens, who had never really had the kind of teen-age fling all girls want and should have. “Settling down” was fine for me, I had my work, and besides I had been all over the world, met all kinds of people. I knew what I wanted, and snuggling up to the fire in our storybook house was it. Or so I thought then.

Gwen and I were having more and more arguments. She was nervous and restless. And I think it is only fair to say, in my own defense, that I had been working very hard and was tired. When you’re touchy and tired to begin with, little things can upset you worse than big ones.

At one point, we agreed that we must reach a better understanding—or call it quits, and we tried to talk things out, but very superficially.

I think things would have come to a real crisis a lot sooner than they did, except that in August, 1946, baby made three. Our daughter, Donna.

This big new interest for both of us dissolved, for a time, the little bitternesses which were gnawing at our marriage.

Gwen was a radiant, eager mother, and I caricatured in my performance all the expectant father jokes you’ve ever heard.

I paced the floor for nineteen hours at the hospital, and then after I had seen that thing (and Donna, aged twenty minutes, was a thing), she looked so exactly like me, I complained to Gwen!

“What on earth have you been doing in there all that time,” I said.

She laughed. “I wasn’t ad libbing, honey,” she said.

And for all the world as though I had done it all myself I tore around town all night, greeting total strangers with “A toast—to the new Queen!”

With Donna to fuss over, Gwen found a new interest in life. Now she could come to the dinner table at night with as interesting a day to recount as any of mine.

But little babies get to be big babies, and quicker than you’d think they then get to be little people with friends of their own and much less need of the one hundred per cent attention of mama.

The baby’s growing independence meant more time on her hands for Cwen. A lot of young wives, I realize, have more than they can manage with a little child in the house, cooking, housecleaning, and laundry to do, but we were lucky enough to afford domestic help. We had a maid to do the heavy housework, and a nurse to help with Donna. Gwen, in a sense, was unemployed, and just as unhappy about it as though her joblessness stemmed from economic causes.

So it happened.

I came home one night creaking with fatigue. Gwen was looking very pretty as usual, and, as usual of late, I forgot to mention it. She had cooked my favorite dish, Irish stew, and I forgot to mention that. “Well,” I said, finally, pushing my plate aside, “did you have a nice day?”

“No,” she erupted. “I had a very dull day. And I’m bored!”

There are the blind who can’t see and the blind who won’t. I had been one of the latter. But I was not stupid enough to go on misunderstanding, once I had been hit on the head with a rock.

“Do you want to go out somewhere?” I asked her. But it was too late.

Gwen thought we should separate. She said she probably would want a divorce.

What could I say? Once she lifted the curtain a little on what her life had been, I couldn’t blow my top and make like I was abused. So I told Gwen she was absolutely right. I was sorry, I hoped it wasn’t really too late to fix things up.

We had a nice, civilized talk (and my insides were bleeding), and I agreed that I would come and see Donna often and we’d see one another from time to time and I told her to get out and have fun, and, well, we’d see. I packed a suitcase and drove to a friend’s house.

First thing, next morning, I rented myself a beautiful bachelor apartment. I never moved into it, thank heaven.

I worked all that day with lead in my chest. Id be all right, I told myself, when I got out of the studio and could look up some pals and go out on the town.

But when shooting was over, I was in no hurry to leave the set. I wasn’t sure just yet what pals I was going to look up.

I finally got out in the evening air, and cheered up a bit. I put the top down on the car, and drove into town. I tried to sing a little song, gay bachelor stuff.

The song was sour, so I began to think about people to call up. I couldn’t think of any peop’e to call up, except Gwen.

I thought about how I would go about winning her back. I’d ask her over to my apartment for one of those intimate little bachelor dinners, with candles on the table, and wine icing in a silver bucket.

I drove by Peggy Ryan’s house, and the lights were on. I could ask Peggy if she would like to take in a movie. So I went in, and Gwen was there.

She wanted Peggy to go to a movie, too.

“You kids are crazy,” Peggy said, exasperatedly, “you go to a movie. And then go home and make up.”

“No,” I said nobly, “Gwen wants her freedom, and she has every right to it.”

“I guess if I can have it,” Gwen said, at that, with just a trace of a quiver, “I really don’t want it.”

So, we did go home and make up, like the nice lady said. We sat up and talked until long after midnight.

If we loved one another too much to divorce, we decided, then we’d have to try to love one another just a little bit more, enough to stay married.

We agreed, in the first place, that the only real satisfaction in love comes from giving happiness to one’s partner.

If my honest desire is to make Gwen happy, then I am more concerned for her frustration and loneliness than I am for my own fatigue. And, similarly, her concern for my overworking will modify her feelings about those “dull” evenings by the home fireside. We can both give up pleasure, for Donna’s sake, such as in our recent decision about the Berlin trip.

We have had other spats, of course, but I defy any married couple, teen-agers or not, to say that they haven’t. We used to laugh at all those column cracks to the effect that we were secretly separated, or even divorced. Now we are annoyed. It makes us sound irresponsible.

From the night of our long, heart-to-heart talk, Gwen and I have been building our marriage on a firmer foundation.

I have come along so far in my campaign against jealousy that I actually find myself beaming with pride when strangers turn to look at Gwen in a restaurant.

Gwen has worked out a new slant on her career problems. The Great Big Break hasn’t come along yet. But she’s had several picture roles and in the most recent one, “Highway Patrol,” she really stands out.

One thing more. Our actually pretty mature behavior when the big crisis came, the fact that we faced our “separateness” with understanding and not with abuse and denunciations, made it much easier to start anew. Knowing that each of us can have our freedom at any time, with no recriminations, no strings attached, operates somehow to make that kind of freedom unimportant. As long as it’s there for the asking, we don’t want it.

We have faced the fact that when people marry young, they still have a lot of growing up to do, and it’s fatal unless they can grow together, gradually, and in the same directions.

So far, our new approach has worked, worked like a dream.

We want nothing more, the three of us O’Connors, than for it to go on working.

THE END

—BY DONALD O’CONNOR

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JUNE 1950

No Comments