Monty’s Brush With Death

PART II

WHAT HAS GONE BEFOKE: In the March issue Part I of the life story of Montgomery Clift began. A tense, confused young man, Monty is nonetheless one of the most vibrant and talented actors in Hollywood. His present troubles tend to obscure his basic warmth and decency. PHOTOPLAY now brings you the second part of the story.

On the night of last May 13, 1956, Elizabeth Taylor and her husband, Michael Wilding, gave a party for a small group of friends at their home in Benedict Canyon, West Los Angeles. Those present were Kevin McCarthy, Rock Hudson and his wife, and Montgomery Clift.

It w as an evening full of tension. The Wildings were then on the verge of breaking up their marriage, and Clift seemed disturbed at this prospect. He also was severely fatigued. At the time, Monty w as in the process of shooting “Raintree County,” and, as usual. he was hurling himself into his work relentlessly, sparing neither himself nor his associates, continually demanding extra effort in every scene.

Throughout most of the evening he sat alone, as though brooding over some excruciating inner dilemma. He was not drunk, as has been reported. The fact is, Clift is not a drinker; one or two highballs intoxicate him almost immediately. Around midnight he decided to leave. Neighbors later reported hearing loud, angry voices at that time, but upon being questioned closely, they said that the voices might have been more “excited’’ than irate.

AUDIO BOOK

Clift had said he would follow Kevin McCarthy’s car down to the point where Benedict Canyon spills into Sunset Boulevard. That was reassuring to everyone present. Clift’s friends were worried about him; most of his friends are continually worried about him. He seems to have well-defined tendencies toward self-destruction.

The two cars departed. A few minutes later there was a shattering, ear-splitting crash, and immediately afterward McCarthy reappeared at the Wildings’ house. He said that Clift’s car had had a terrible accident. He rushed to the telephone to call for assistance. Miss Taylor suddenly screamed, “Monty! Monty!” and started to run outside. The others tried to hold her back, but she was not to be held.

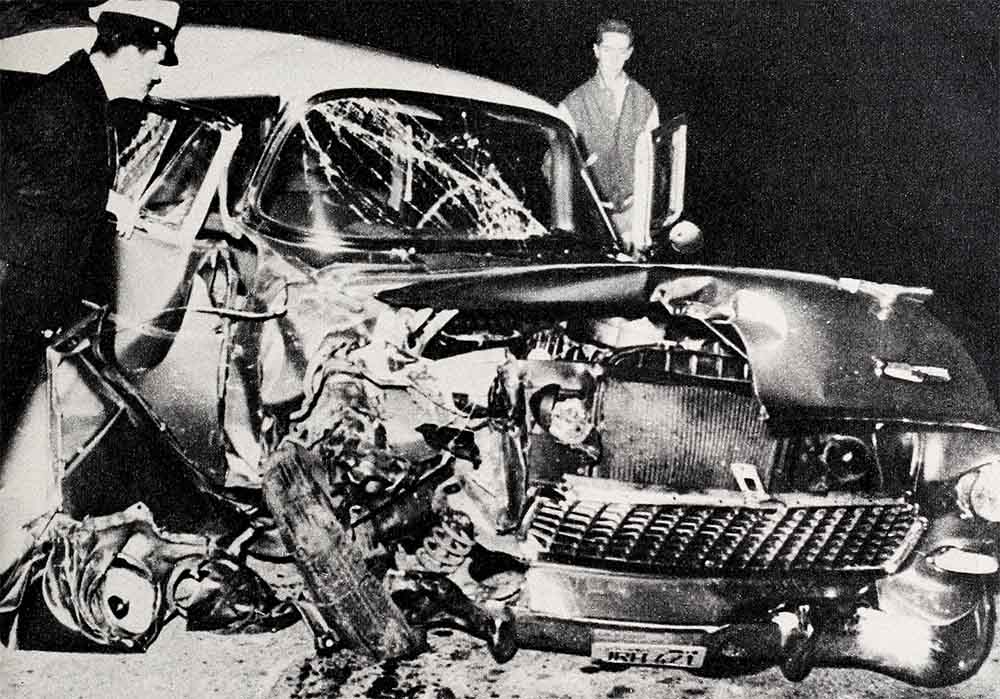

Clift had missed a turn. His car had smashed into a roadside tree. It was a mass of twisted wreckage, ready for the junk heap.

Dr. Rex Kennamer, a doctor regarded highly in the West Los Angeles area, arrived in a short time. He found Clift still in the front seat, bleeding profusely from cuts on the face. Miss Taylor was holding his head in her lap, making comforting sounds between sobs. Dr. Kennamer later declared that it was a miracle the actor had survived his crash.

“We were sure he was dead,” McCarthy later reported to a young actress friend, Barbara Gould. “We couldn’t understand how a man could bleed so much and still live. There were even pools of blood on the road.”

Clift suffered a brain concussion, severe cuts of the face, a fractured jaw and a badly broken nose. For a time it was feared that his face would never be sufficiently mended for him to be a movie star again.

As they were taking him out of the car, Clift came partially back to consciousness. His eyelids fluttered and he began to mumble. His words were later reported by one of the men who helped extricate him from the wreckage. They were indistinguishable at first, but then one phrase became audible:

“If only I’d been able to do it. If only I could have done it . . .”

Then he lapsed into unconsciousness and they took him off to the hospital. What he meant he could not—or would not—later explain. Montgomery Clift has a determinedly reticent nature and an apparent unwillingness to evaluate himself in realistic terms. Perhaps he was reluctant to face the possibility that he wanted, to harm himself severely.

Clift at that time was a disturbed human being. Many of his friends were saying, “Monty is his own worst enemy. He seems to loathe himself.” Other events that happened after his recovery, when he had gone back to work on “Raintree,” seemed to bear out those statements.

As shooting progressed, Clift’s awkward, graceless movements seemed to make him easy prey for accidents. “Monty is the worst-coordinated man I’ve ever seen,” said Millard Kauffman, writer of the “Raintree” script.

Apparently this was right. One moming in Natchez, Mississippi, Clift started running for the limousine that was to carry him to the “Raintree” location set. At the same time, a young girl ran up to ask him for his autograph. Clift slammed into her and knocked her down. The girl suffered a sprained ankle. Later, on the set, Monty tripped over a rock and fell flat on the ground, sustaining a slight cut over his left eye. In Danville, Kentucky, he stumbled again and broke his toe.

The latter accident was only one of many delays in the shooting of the picture. It infuriated his co-workers. “All right,” one said later, “so he’s got a broken toe. So he’s out for a couple of days and then goes back to work. That doesn’t make him a hero. If he hadn’t been so careless, he wouldn’t have broken the toe in the first place.”

Eva Marie Saint, who was in Danville with the company, reports that many times she had cause to worry over Clift’s seeming disregard for his own safety. “There was one scene where he had to run and swing aboard a moving train,” she says. “He began running for it, and I couldn’t look. I was certain he was going to miss. It didn’t seem possible that he could make it but, thank God, he did.”

When Clift’s minor injuries caused delay in shooting, he was frantically apologetic to cast and crew alike. One day he came down with a severe toothache that later proved to be an ulcerated jaw. “He went around explaining it to everybody,” one sound man says. “And it seemed to me that in the very explanation he was relishing the fact that he was in pain.”

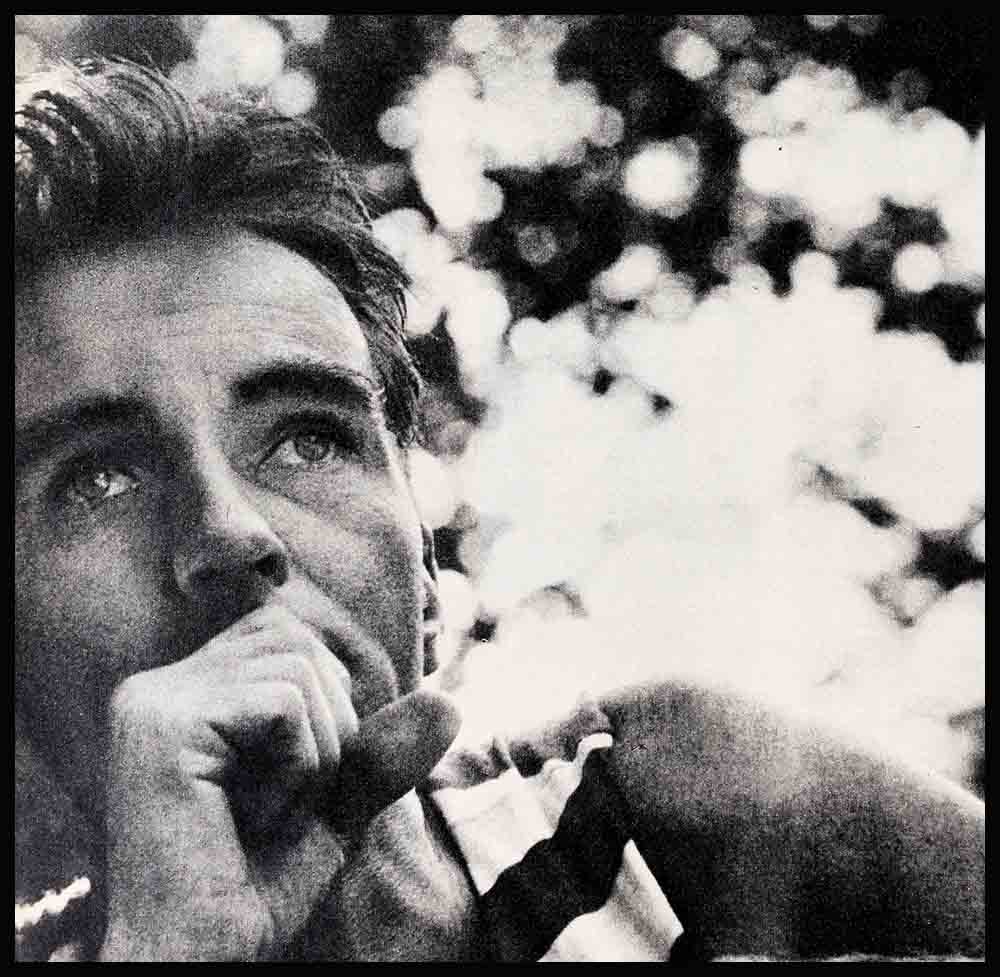

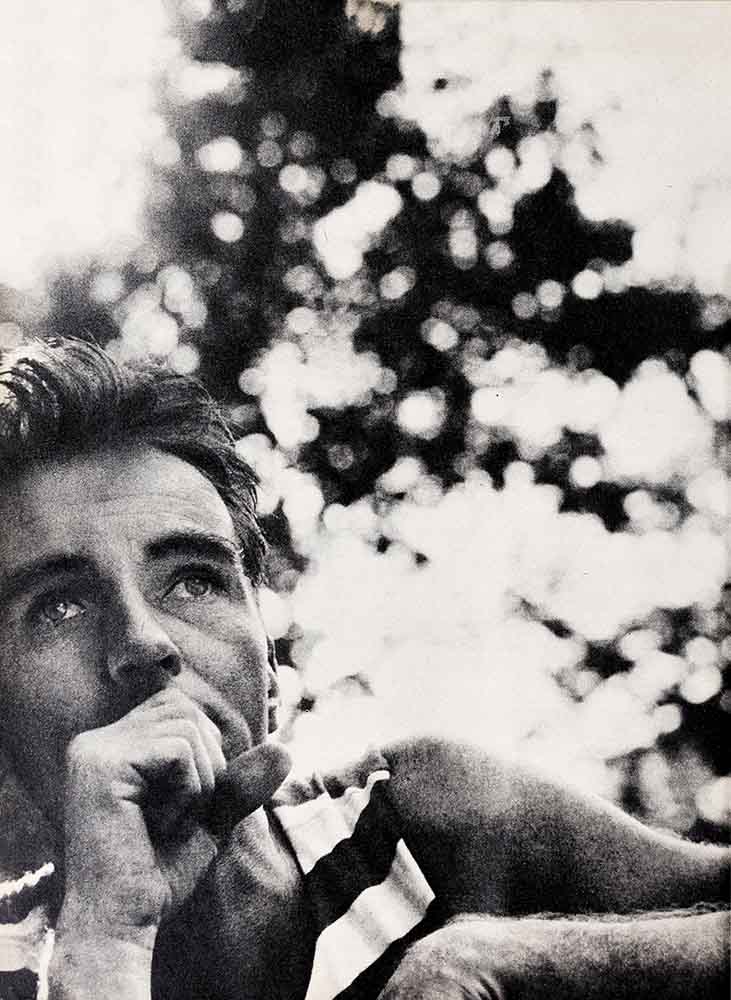

Clift is extraordinarily soft-skinned. “His emotions,” says one friend, “are just beneath the surface. He’s as sensitive as an overbred kitten. We were watching some ‘Raintree’ rushes in the projection room one day, when all of a sudden a terrible, racking, death-rattle of a sob broke out of him. Even though it was his own performance he was watching, he was so moved he had to rush out of the room.”

Such mysterious, compulsive behavior is all the more bewildering when one considers that Clift ought to be at the peak of his powers. He has one of those faces which seems to improve with age. “Women go for that drawn, haggard look more than they go for the clean-cut type,” says Kendis Rochlen, the Los Angeles columnist. Many agree. Monty, however, finds a certain disadvantage in his looks, despite feminine approval.

“He feels he’s getting typed,” says a friend. “He’s always playing the brooding, unhappy kid—the Monty Clift type, you might say. He wants to do something more challenging.”

Still, every role challenges him, within its limits. Actors who have worked with j Monty attest to the fact that he is hard on himself.

The truth seems to be that Clift’s odd approach to life is rooted in emotional turmoil. There are a few keys to his present personality, though they are difficult to find. His parents, immediate family and close friends have entered into a tacit understanding which forbids them from discussing him frankly. Nevertheless, what stands out is striking.

Edward Montgomery Clift was one of a pair of twins born to Ethel and William Brooks Clift on October 17, 1920, in Omaha, Nebraska. His twin sister, Roberta, is now Mrs. Robert McGinnis of Austin, Texas. His older brother, William Brooks Clift, Jr., is a television producer in New York City. Monty’s father has always been a business executive—first a banker, later an investment counselor. After working in a bank in Omaha, the senior Clift went on to other financial positions in Kansas City, Chicago, and eventually New York.

“We are very conservative people, because of my husband’s business,” Mrs. Clift said recently. “We do not like to discuss our private affairs for that reason.”

Mrs. Clift did say, however, that in her opinion Montgomery was a normal child But she added that he had always been thin, highstrung and extremely impressionable. His sister confirms this view. She declares that on occasion, when Monty’s mother was reading him a story the boy would become so aroused that he would burst into tears. But neither his sister nor his mother feel that Monty’s sensitivity was in any way connected with his home life as a child. They believe that he was “nervous” from birth.

A doctor in Hollywood who once met and spoke at length to Clift concludes. “Obviously, the young man is the product of a childhood in which he felt he was not getting his due of love and affection. This is often the case with twins; one will feel that the other is getting all the attention. It is also familiar in the case of children whose brothers or sisters are not much older. Clift’s brother Brooks is only about eighteen months older than the twins Furthermore, the parents led an active life. They moved around a good deal and often went to Europe on long visits. Continuous travel can operate to the disadvantage of the insecure child.”

Clift himself once remarked to reporter Eleanor Harris, “I call all that traveling a hobgoblin existence for children. Why weren’t roots established? Look at my brother. He’s been married three times.”

In one sense, the “hobgoblin existence” actually worked to Monty’s benefit. A craving for affection frequently brings out talent which perhaps might not develop if the person were altogether adjusted to life. By becoming an actor, Clift was not only bidding for attention outside his family, but also striving to prove his worth within it. He himself admits that his desire to go on the stage was rooted in a need to compete with his sister and older brother.

He was thirteen when the decision was made. His father had had a financial disaster and needed to do more traveling than ever to get back on his feet. He decided to establish a residence for his wife and children in Sarasota, Florida. While there, young Montgomery heard of an amateur group that was putting on a play called “As Husbands Go.” He went around to find out “if they had any parts for boys.” I They did. His career was launched.

The conservative William Brooks Clift was never altogether happy with his son’s choice of a career. Acting, he pointed out, was a highly unstable profession. This it might be, Monty agreed, but he loved it. Besides which he had special needs. Needs developed by his love-starved family life and encouraged by his consequent lack of communication with other children.

As a youngster Monty never had any special friends. A girl who knew him in Florida says, “He kept to himself. He was always polite, but there was something brooding about him that held others at a distance.” In the theatre Clift found some of the emotional satisfaction he needed. He could establish contact with his audience and receive warmth, affection and approval without giving anything of himself emotionally to another person.

Even today Monty remains withdrawn. Elizabeth Taylor, calling him “my closest friend” in one breath, admits in the next that she is not certain she understands him. Norman Mailer, the novelist, says, “Monty is one of the few people I’ve known for years of whom I can say, ‘I don’t know him at all.’ ”

From Florida the Clifts moved to Connecticut. That was in 1935. Young Monty began going to New York, looking for acting jobs. Thomas Mitchell, the veteran character actor, was planning to try out a show called “Fly Away Home” in summer stock. Clift read for the part and was hired. His parents gave their reluctant approval, then kept a close watch on him. His mother accompanied him to the theatre, waited until he had done his nightly stint, then took him home. Such close supervision often causes conflicts in a youthful, impressionistic mind. On the one hand, there is a need for love and attention; on the other there is a growing need for independence. A companionship between parent and child that is too close inhibits the natural development of maturity.

These conflicts in Clift explain in part his inability to form a permanent, lasting relationship with any woman approximately his own age. There have been girls in his life, but none has remained long. Judy Balaban (now Mrs. Jay Kanter), daughter of a motion picture company executive, was seen with him frequently for several months, and was said to have been in love with him. It was more a schoolgirl crush than anything else. But Clift could not reciprocate. Today, Mrs. Kanter does not like to talk about the involvement.

The most important woman in Clift’s life has been Elizabeth Taylor. She went about with him before and after her marriages to Nicky Hilton and Michael Wilding. A former M-G-M press agent recalls meeting her once at Idlewild Airport in New York, with a limousine and chauffeur. She refused to drive back to the city in the studio car, preferring to ride in Clift’s. But although Monty is as close to Miss Taylor as he is to any other woman, he evidently was unable to permit his friendship to develop into love.

“Monty is like a schoolboy who worships from afar,” one friend says. “In Hollywood, around the time he was finishing ‘Raintree,’ he had one of his crushes on Jean Simmons. But Jean is happily married. You see, Monty only permits himself to get involved with women with whom no real relationship, no marriage, is possible.”

Libby Holman, a singer who is nearly fifteen years older than Clift, is his most constant companion.

I “He’s very happy when he’s with Libby,” one of Clift’s friends says. “Possibly because he’s found in her the mother he was looking for and never found in his own mother.”

Clift snorts at this explanation. all he will say, however, is, “Libby is one of my very closest friends. She’s a wonderful person.”

After “Fly Away Home,” which played in stock and then ran seven months in New York, Clift’s destiny was sealed. He would not think of anything but acting as a career. His schooling had always been haphazard—he’d had a succession of tutors and had only gone to one school, a private one in New York, for a year. Now he abandoned all thought of formal education and threw himself into the business of carving out a stage career.

“Monty haunted the theatres,” a friend of those days recalls, “and when he wasn’t seeing plays or looking for work, he was over in the Public Library reading about the theatre. I’ll bet he read every book on the stage ever written.”

Clift’s first break in the theatre was followed closely by his first big disappointment. He was up for the part of the oldest boy in “Life With Father,” and was being considered for the role by the authors, Howard Lindsay and Russell Crouse. “We finally decided against him,” Lindsay recalls, “because he was a little ‘special’ . . . he wasn’t quite the lad of the Nineties we had in mind. He looked a little too intellectual.”

Clift was nearly beside himself with disappointment. He was certain that some aspect of his acting had caused him to lose the job, and he threw himself into his work with even greater intensity. It is safe to say that few actors in the history of the American theatre have demanded so much of themselves in preparing for roles—even small roles. When a part required that the character imitate a dog barking, Clift studied with a professional animal imitator until he had mastered the proper barks. When another role required him to pretend to play a flute, he became a passable flautist. Before reporting for work on “Red River,” his first movie, he became an expert horseman.

“Red River” came after Clift’s unprecedented intensity had carried him through a succession of smash hits on Broadway: with the Lunts in “There Shall Be No Night,” with Tallulah Bankhead in “The Skin of Our Teeth,” in “Our Town,” “The Searching Wind,” “Foxhole in the Parlor,” and “You Touched Me.”

He was also with Fredric March and Florence Eldridge in a play called “Your Obedient Husband,” at which time he suddenly came down with a case of mumps, promptly picked up by several other members of the cast. “It wasn’t Monty’s fault, but he felt personally responsible,” says the press agent for that show. “We all pitied the kid; he took it so hard.”

This is one of the few instances on record in which a press agent expressed any sympathy for Clift. He was, and is, t the bane of all publicists’ existence. He often refuses to show up for interviews, cancels appointments with writers and in general treats reporters with scorn. A Hollywood newspaperman once encountered him in Martindale’s bookshop in Beverly Hills, moodily paging through a copy of Dostoevski’s “The Brothers Karamazov.” “Hello, Monty,” he said cordially. Clift looked up like a frightened deer, hastily put down the book and scurried out of the shop.

Clift’s major success on Broadway came during World War II. A chronic ailment of the colon, which Clift (who fancies himself a medical authority) says he picked up on a trip to Mexico, kept him out of the service. Subsequently his career in New York prospered. Before long he was much in demand, and before long his temperament began to assert itself.

One hot summer night during the run of “Foxhole in the Parlor,” Monty made the theatre hands turn off the air-conditioning equipment, explaining to the management that it was interfering with his performance.

“He was a calculated eccentric,” says Richard Maney, the noted Broadway publicist. “He could have given lessons to Brando, whom he preceded in the goofy department. That may be why he and Tallulah got along. That is, at least she spoke to Monty, which was more than she did to Brando when they appeared together.”

Most of Clift’s eccentricity was not calculated, however. Somewhere along the way he developed a genuine passion to live his own life, alone and undisturbed, something few stars ever have been able to achieve. Part of it may have been due to the restraining influence of his parents in his early years. And part of it may have been due to his belief, developed in childhood, that nobody loved him or cared about him. To compensate for that, he chose to go it alone, as though to prove to the world that it didn’t really matter whether anyone cared for him or not.

So he lives today virtually alone. He has a secretary, Marjorie Stengel, who takes care of his appointments and helps protect him from the world. In his New York apartment, a duplex in the East Sixties, a housekeeper comes in and cleans for him; in Hollywood, in the secluded furnished houses he sublets, he employs an Oriental houseboy. He regards the New York place as his real home, and when he is in town he will shut himself up in it for days, never answering the telephone, rarely bothering to dress except in a bathrobe, reading and listening to his large collection of records.

“Monty may be in town for weeks and you’ll never hear from him,” says one friend, “and then, all of a sudden, you’ll see a good deal of him. That’s Monty; you have to get used to his moods if you want to keep him for a friend.”

Clift himself sees nothing unusual about this behavior. He blames everything on the extreme concentration he brings to each role. If he appears in a restaurant without money, as sometimes happens, he shrugs, as though to explain that he was thinking of something else while he was dressing—which, in fact, probably was the case. “I don’t believe he knows how much money he has,” says Laurence Beilenson, his attorney and business adviser in Hollywood. “He’s not rich, as some stars are, but he’s comfortable. Yet I get the impression that even if he were broke it would not matter much to him.”

A good deal of his money goes for travel. Whenever he can get away, he’s off—Europe, Cuba, Mexico. Sometimes he travels with Kevin McCarthy and his wife Augusta Dabney, regarded by other friends as Clift’s “substitute parents.”

“He’s still looking for affection, still searching,” one acquaintance has said. “In that sense, the travel is symbolic. And in that sense, he’s never grown up. He’s still a little unloved boy in his own mind, trying to resolve the conflicts developed in childhood, and yet unwilling to grow up and face himself as Monty Clift, the man.”

That may be the most important key to the character of this complex, fascinating personality, a personality which has developed into one of the finest acting talents of our time, as well as one of the most puzzling eccentrics in a world of oddballs. At this writing, Clift seems to be faced with the choice of growing up or cracking up. The path he chooses is solely up to him. His many fans and friends devoutly hope it will be the former.

THE END

PLAN TO SEE: Montgomery Clift in M-G-M’s “Raintree County.”

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE APRIL 1957

AUDIO BOOK