Ava Gardner’s Dry Tears

Ava Gardner, who claims she prefers everything Spanish to anything American, sat in the darkest corner of the bar of the Castellana-Hilton Hotel in Madrid. The Hilton bar is about as Spanish as the airport at Kansas City, Missouri.

It was eight o’clock and pouring rain outside. I had received a message to meet Ava at the Hilton only fifteen minutes before.

That’s Ava. I had been in Madrid for three solid weeks and she knew it. A year ago, in London, Ava had given me the only personal story she’s granted anyone in two years. When I planned to take a trip to Spain I wrote her from Hollywood just where I’d be, and when, and said if she wanted to talk again I’d be happy to listen. She didn’t answer.

AUDIO BOOK

When I arrived in Madrid I sent a note around to her. You can’t telephone her for the extremely simple reason that she has no phone. You can’t “drop in” on her because, while every taxi driver in Madrid knows where she lives, she knows every one of them, as well, and she ducks when she sees one coming. You can’t mail a note to her house, either, because she doesn’t get her mail there. She gets it at another address and this is secret, so to reach her you have to go through a friend of a friend of a friend.

Why all this secrecy? I don’t know. I doubt if Ava knows either.

But on this particular rainy day, when the Spanish papers had picked up a yarn published the day before in America to the effect that she and Frank were reconciling, it didn’t surprise me to get her message.

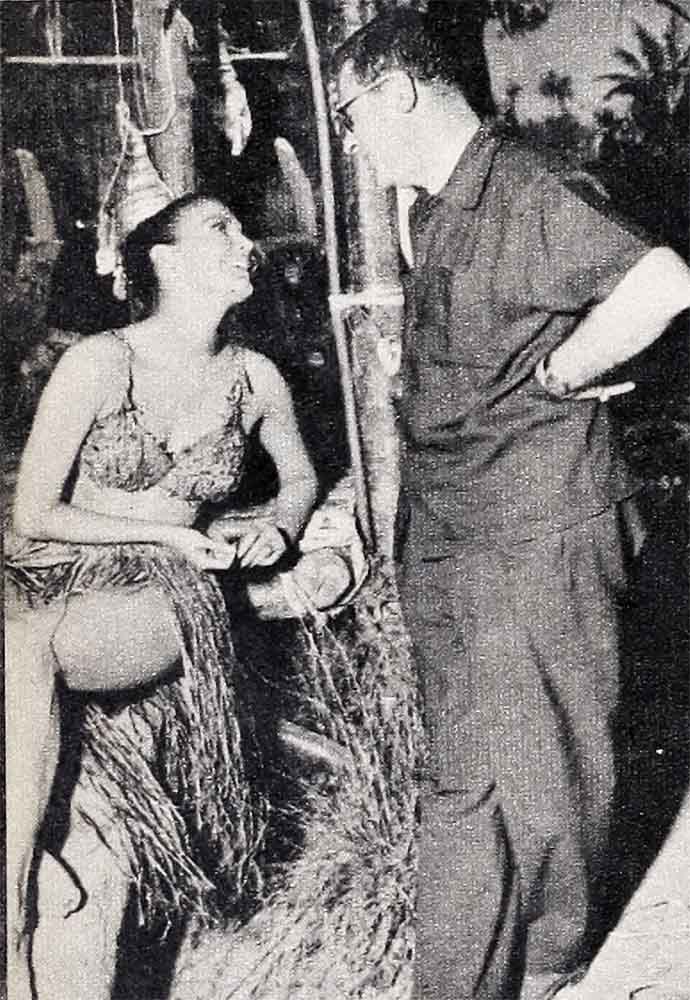

So there I was, in the Hilton bar, in response to her summons; and there she sat with a handsome gentleman on either side of her and another across the tiny cocktail table from her and all drinking martinis.

She never looked more ravishingly beautiful. Her dark hair was pulled straight back from her lovely face and fastened in a small bun. She had no makeup on except lavish, deep red lipstick, and wore no jewelry.

Heaven only knows how she maintains that beauty. By her own admission, she lives entirely on Spanish food, which is just about the most fattening in the world. She’s always been a heavy drinker. She goes night after night without sleep. Yet not one wrinkle mars her exquisite face. There are no circles under her eyes and not one line of her flawless figure has coarsened. Last summer, she was wearing her hair pulled back tight and fastened atop her head in a little bun. This wasn’t the studied simplicity of an Audrey Hepburn. Ava’s hairdo was like a farmer’s wife who had yanked her hair back for coolness on a hot day and nailed it down, atop her head, with very visible hairpins.

This deliberate artlessness, this defiant naturalness, is part of Ava’s general attitude in Spain. In a country so formal that housemaids wear gloves to market, Ava often goes barefoot.

But at the moment I looked at her, across the carefully shadowed room, I saw that I was already too late. Ava was already hostile, a mood I know too well from the past. It is not a personal hostility, but one which Ava holds against the world in general. From the day Ava first landed in Hollywood, she’s always had it, and now it’s getting worse. Why does Ava who has everything—beauty, youth, fame, fortune, freedom—hate everything?

When Ava called and made this date for us to talk, she had been merely angry. She had said, her voice shaking with fury, “Well, here I am getting the worst of it in the papers again. This time, believe me, I want to tell my side of it.”

The rumor that Frankie and Ava were reconciling was spread while Frank was in Spain making “The Pride and the Passion.”

Now, if Frank and Ava were two sensible people that untrue bit of news wouldn’t have got their backs up. If it had been true it would have been charming. But since it was false how could it hurt them? Actually, at that time they had seen each other only once, and then by accident, at Madrid’s fashionable Restaurant Commodore. Frank was in one party. Ava was in another. There were some beautiful young ladies in Frank’s party and some handsome young men in Ava’s. In other words, it was a stalemate for these once-great lovers who are now a not-quite-divorced husband and wife.

In 1950 Ava and Frank had defied society and tagged after each other all around the f world, even though Frank was still very much married to Nancy. They had even been in Spain together in 1950, while headlines thundered and Nancy Sinatra’s heart broke. They had married each other in 1951. But last summer there was the daily irony that, in order to get to the location for “The Pride and the Passion,” Frank had to drive by Ava’s magnificent, modernistic, red-brick house morning and evening. But never once had he stopped to see its fabulous interior, its lavish gardens, or Ava.

Frank and Ava, of course, are not sensible people. Sensibleness is not the stuff of which such stars are made. Thus, last summer Frank not only sent out a thunderous denial of the reconciliation report, but he threatened to sue the next person, publication or news source that repeated it. In fact, he worked himself up into such a State of nerves that he had to retire from playing in “The Pride” for a whole week, which cost that production untold sums of money.

Madrid’s Ava Gardner, glancing at the gentlemen sitting on either side of her in the Hilton bar, said, “You know these two and I do wish I could introduce you to the character standing beside you, but I can’t pronounce his name. I call him ‘Little Flower.’ It really sounds something like that. I’m embarrassed to admit that after two years in Spain I still can’t pronounce Spanish properly. I can’t really hold a conversation in the language. Isn’t that awful?”

“Little Flower” threw her a mocking glance, even while he gallantly kissed my hand. They made room for me at the table.

Looking at her that Spanish midsummer night, I wondered what had happened to the girl I had met, by the sheerest accident, on her first night in Hollywood sixteen years ago.

Ava Gardner was nobody then. A young agent who had met her in New York and had brought her out to Hollywood to show her off, called me up and asked if he might bring her to a party I was giving.

Naturally, the moment Ava walked in the party was ruined. The men present were knocked speechless. They had never seen so much young beauty before in their lives, and I doubt if they ever will again. The women were kayoed, too, not only by Ava, but by the men’s reaction to her. The conversation died, so that we were all relieved when she and the agent left. Everybody else left right after them. There was no putting that party together again.

A few weeks later I heard that Ava Gardner had an M-G-M contract. That was a very big break in 1940. Then early in 1942 the whole world learned that the shy girl from Smithfield, North Carolina, had married one of the biggest stars on the screen, Mickey Rooney.

Right then, if those of us around Hollywood had only been smarter, we would have seen that a pattern was being set.

For Ava had met Mickey the first day she went to M-G-M. Mickey, the king of the box office, and many inches shorter than Ava (interestingly enough, so is Frankie shorter than she, and Mario Cabre as well) was then making “Babes in Arms.” Mickey took one look and was doomed. The publicity man who had introduced them to each other said to Ava, “Now that you have met Mickey Rooney I hope you’re happy.”

Talking about it later, Ava said, “That remark hurt me so I almost burst into tears. I wasn’t star-struck.”

That, you see, was the beginning of the pattern. That was the mood that still drives Ava. She was being abused. She was being misunderstood. She must have liked meeting Mickey. Who wouldn’t? He was then the most important guy in town. You can only presume she later fell in love with him. Certainly, she married him—and very, very soon divorced him. She was in pictures with him. Besides, underneath all his flamboyance and his great talent, Mickey was an appealing guy. Nevertheless, the first time anybody made a remark to Ava about Mickey, she got “hurt.”

Also, with Mickey, she began another pattern. After she got her divorce from him, she and Mick “stayed friends.” Ava remained “friends” with Artie Shaw, too, after they were divorced, following their marriage of less than a year. And right there is one of the things I think ails Ava now. She wants to “stay friends” with Frankie. Only Frankie isn’t playing.

The saga of her Sinatra romance was fabulous. It began late in 1949. Frank was still married to Nancy, his childhood sweetheart, and they had three children. But that hadn’t stopped a lot of other girls, and it didn’t stop Ava either. The difference was that the other girls were dropped by Frank after various casual intervals, but Ava stuck.

All the evidence seems to prove that Frankie must have been madly in love with her. Certainly he went through enough to get her. He paid a colossal settlement to Nancy, he gave up his home and he gave up his children. He was and is a very good father, so this must have hurt him. Then, after he and Ava finally were married, he tried hard to hold on to her.

Yet within a year after their marriage the divorce rumors were flying. So were Ava and Frank. She went to Spain and he flew after her. She went to Rome and he flew after her. She went to London, ditto. Once he chartered a plane all the way from New York to Madrid and when he arrived Ava wouldn’t see him. But other times she did, and those times they fought and made up and made up and fought. Finally, in the fail of 1953 Ava went to Nevada for her decree. When anybody asked her what the grounds would be, she airily said: “The usual.” In other words, mental cruelty, which is sufficient grounds in Nevada.

Only Ava never did pick up those divorce papers, which means that technically she is still Frank’s wife. If she’s really through with Frank why is she so interested in him? Why, for instance, did she have a print of “Man With the Golden Arm” shown just for her in Madrid—and in the middle of the night, so that nobody would know about it? And if she didn’t want anyone to know, why did she cable Frank how good she thought his performance was?

In 1955, in London, Ava started telling me these things about Frank and herself, and in particular her resentment that his turning down “Saint Louis Woman” left her stuck with that extra year on her M-G-M deal. Then, just as she was blasting away at Frank, calling him every name in the book and quite a few which are never printed, she suddenly stopped. So help me, she went over to the record player in her elaborate London flat, put a Sinatra disk on it, listened, drew a deep sigh and murmured: “Isn’t he the greatest? Isn’t he the living end?”

Thus, seeing her in the Hilton bar, I had a hunch she was going to be just as outraged, if not more so. Ava’s outrage is constant, like her beauty, which is still the same breathtaking, dark, sultry beauty as always, only more lush, more dark, more compelling.

Frankie isn’t everything that ails her, but he’s a good strong Symbol of it. Ava is also in conflict about her work. Even when she was married to Mickey she talked about retiring. When she was married to Artie and was going to college at UCLA she went on and on about giving it all up and just having babies. And she said she’d adore having children when she was first married to Frankie.

Then, there’s been resentment against her producers. When I talked to her in London a year ago, and again when we talked in Spain, she did nothing but blast M-G-M, to whom she has always been under contract, and who has given her nothing but fine pictures and an astronomical salary. “The Little Hut” was already prepared for her when I talked to her. I asked Ava if the idea of forty Dior outfits to wear in it excited her. She said no. I asked her if the picture itself excited her. She retorted that her part in the picture was lousy and David Niven and Stewart Granger had the really good roles.

Before I could think of an answer to that Ava switched subjects and began talking about flamencos. Flamencos, as you probably know, are a kind of jam session of Spanish dancing. A flamenco may take one guitarist or ten to begin with, one dancer or two dozen to respond to their rhythm. They seldom start before midnight, seldom end before dawn. Ava’s flamencos, which go on virtually every night at her house, are the talk of Madrid. Often they go on until noon of the next day. Then she sleeps a whole day afterwards.

The sleeping all day is nothing new for her. She slept all day long in London, too, while she was doing “Bhowani Junction,” except when she was actually working.

In London, there was young Lord Jimmy Grenville, rich, titled, handsome, an ideal husband. He tagged around after Ava with the utmost devotion and she barely gave him the time of day.

Maybe she wants only what she can’t get and doesn’t want what she can.

Like bullfighters. In Spain they talk about Ava and the bullfighters, specifically a matador named Cesar Ginon and a novillero called Chamanco. Ginon is very old for a matador, being nearly thirty, but Chamanco, the novillero (which just means that he has never fought bulls in Madrid) is barely twenty. They do say, in Spain, that he ruined his career because of Ava—but she just clams up on the whole subject.

While in Spain it’s bullfighters, in Italy it s Walter Chiari, the handsome young Italian comedian. Ava is deeply attracted to Walter and he to her. He has said on more than one occasion that he’s going to marry her. Ava enjoys being pursued and admires persistence and it is altogether possible that she will one day say “yes” to Chiari. Her proposed trip to America, ostensibly to get her divorce from Sinatra, may be the tipoff to future plans. But in the meantime when, oh when, will Ava stop to think how magnificent life has been to her, giving her beauty, talent, wealth and opportunities? She seems to think that life, reporters and M-G-M are all trying to put something over on her, as, for instance, when the studio tried to talk her into making “Love Me or Leave Me.” She said they weren’t going to stick her with that one. You know what a hit that turned out to be—for Doris Day.

It’s all such a shame. Ava has such warmth, when she wants to turn it on.

There that night in the Hilton bar she was like a frightened child, acting full of courage, making believe nothing mattered to her, full of wild defiance. There I was, at her own request, ready and wanting to hear “her side of it.” But her mood had changed before I got there. Her almost morbid sense of personal privacy had taken over—and in a noisy, crowded, public bar, of all places.

I thought, maybe, if I told her how beautiful she was in “Bhowani Junction” she might relax. She was very beautiful. But all she said was that she didn’t know why they didn’t take those startlingly lovely closeups of her at the beginning of the filming when she was fresh instead of at the end when she was tired. I tried again. I asked if it was true that when she found her house in Madrid she lay down on the living-room floor and said: “This is my home.” She laughed. She said she had bought the house because it was a shrewd buy.

Then, without warning, her mood changed and she began to tell a story on herself. She had, she said, gone to her doctor’s the previous day. Her eyes and her ears had been troubling her, and a certain physician had been highly recommended. She looked him up in the phone book and started for his office.

The only address she had was “Santa Barbara,” and in Madrid that could mean a plaza, a square or a Street. So she headed for Santa Barbara Street first, but that was incorrect. She went to the square next, or maybe it was the plaza. Either way, that wasn’t the right one either. However, a bunch of urchins came by and recognized her, greeting her with loud cries of “Ava, Ava,” giving it a very broad “a”. She explained her predicament, whereupon the kids ran in front, on the sides and behind her car, all the way to the right address.

“That’s what I adore about Spain, people being that kind,” she said.

“People are that kind in America,” I said. “Why don’t you come home? Aren’t you lonely here, particularly, if you don’t speak the language?”

“I’m studying more important things,” she said loftily.

“Socrates,” said one of her Spanish friends. “She’s studying Socrates.”

I looked at Ava in amazement, but she nodded her agreement. Then she said: “One more year on my M-G-M contract and I’m free. Free to do exactly what I please, when I please and nothing else but.” She stood up, held out her hand. “Goodbye,” she said. “I hope you got a good story.”

I did, but not what Ava thought I had I’m sure. For I don’t know whether or not this beautiful, famous, rich girl cares that in the battle between her and Frank, I think he’s won another round.

For Frankie, at least, does know where he’s going.

THE END

WATCH FOR: Ava Gardner in M-G-M’s “The Little Hut.”

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE APRIL 1957

AUDIO BOOK