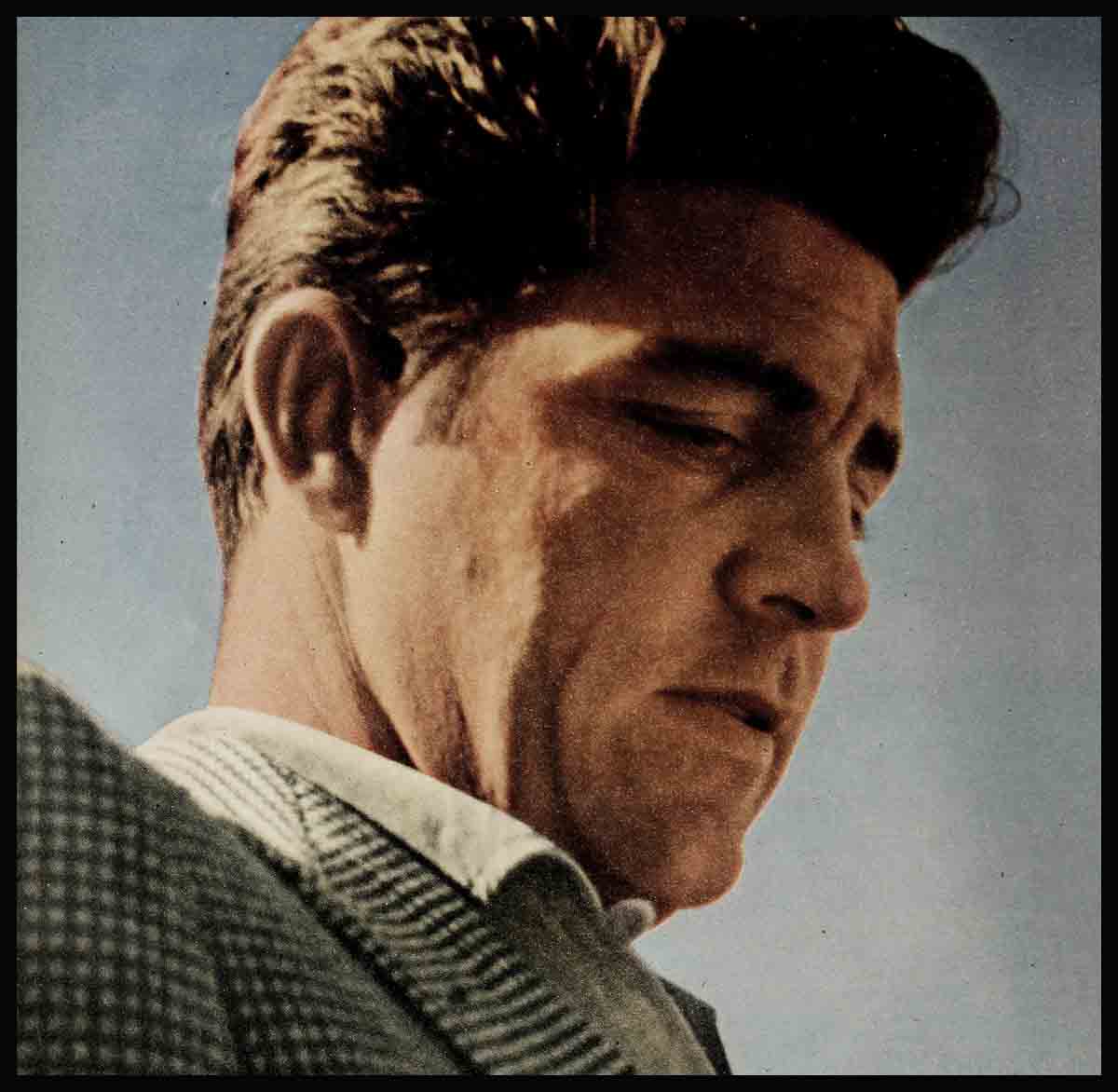

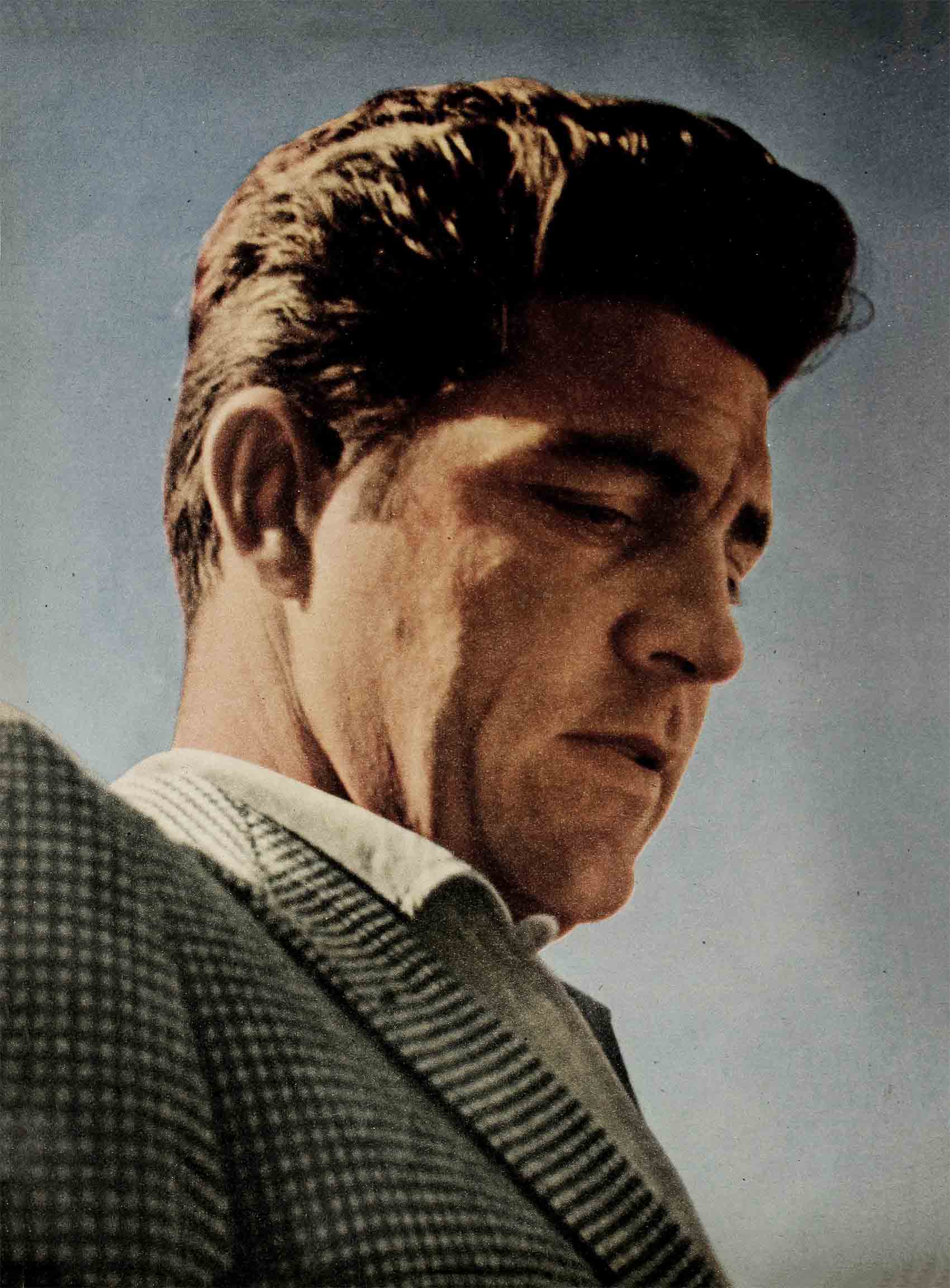

I’m Gonna Quit?—Dale Robertson

No matter what people say about Dale Robertson—that he takes himself too seriously, that he won’t cooperate with his studio’s publicity department or that he is a horse-crazy, frustrated cowboy, the fact remains that he always tries to tell the truth about himself. When this drawling young giant tells you something, he means what he says.

When he says, as he did a few weeks ago, “I’m gonna quit acting ,in another two years,” he means it. He isn’t reaching for a headline or a mention in a gossip column.

Robertson has always insisted that, “I came to Hollywood with one goal in mind. Wanted to get me enough money to buy a horse ranch.

“The way I figured it back then, the way I still figure, is that anyone can become an actor. I reckon you can walk out on Hollywood Boulevard right now and make good actors out of the first ten folks you run into. I’m not saying they’ll develop into stars. Nothing like that. It’s the public who makes the stars, not Hollywood. But anyone can act. When I learned that, I decided to do something about it.”

So he went out and raised all the money he could and bought interest in a manufacturing concern called Everlast Laboratories. Now he’s president of the corporation.

His business manager, Morgan Maree, who used to limit his spending money to $20 a week, tried to persuade Dale not to buy into this business. “Why don’t you invest in an apartment house?” he suggested. “Why don’t you buy some real estate?”

“That’s not for me,” Dale said. “Whatever money I’ve got saved up, I reckon I’ll put it in this Everlast setup. I like the looks of the place. I’ve talked to the chemist down there. We can turn out some wonderful products, products the country needs.”

Other friends listening to Dale told him he was nuts. “Look,” advised one, “it’s only been a year or so that you’ve been earning a thousand bucks a week. Why don’t you invest that dough in blue chip stocks? This manufacturing business is too risky.”

Robertson had heard that kind of talk before. After World War II when he returned to Oklahoma City and told people he was going to try his hand in Hollywood, they gave him the same routine. Too risky, you’ll spend all your money.

Dale drove out to filmland. It was plenty rough before he got his break. “But once I made it,” he recalls, “they all became back-slappers. ‘Knew you’d make it, boy.’

“Same with this Everlast thing. We’re turning out an innertube rubber coating, makes the tires on your car absolutely puncture proof. You squeeze the stuff into your tire tubes. They do it for you at filling stations. Costs $2.50 a tire. An’ for ten bucks you’ve got yourself four puncture-proof tires. It’s a good deal.

“We’ve been selling the compound all over the country. Safety Seal. It’s our own secret formula. And we’ve been in the black since we got under way.

“Funny thing. All these folks telling me I was plumb crazy, now they’re coming around. ‘Dale boy,’ they’re saying. ‘How about buying in with you? How about selling some stock?’ Nothing doing. There’s no stock left. I hocked myself to get things going. Now I reckon I’ll just sit back a bit and see what goes.

“In this company of mine, we got lots of plans. We propose to turn out a special hand lotion for secretaries. Then we got a face cream. We got big plans but we’re moving slow. Maybe I shouldn’t say this, but I’m getting as big a kick out of this business as acting in films.”

The thirty-year-old Oklahoman explained that acting was pleasant and exciting. He was grateful for the opportunity.

“Only thing about it,” he pointed out, “is there ain’t no one can tell you how long you gonna last.”

When Dale was first signed at 20th Century-Fox some of his fellow employees were Linda Darnell, Anne Baxter, Betty Grable, Joanne Dru, Bill Lundigan, June Haver and Gary Merrill. Today, for one “reason or another, they are no longer there.

Early this year when Robertson’s contract came up for renewal, it was touch-and-go whether or not his option would be picked up, despite the fact that for the last three years he has been ranked one, two, three in fan mail popularity. He began to look for additional income.

He had met a chemist, an elderly European, who said he had worked out formulae for many salable products. Dale decided to do some careful investigation.

It all seemed very complicated and anyone else might have dropped the whole thing to concentrate on acting.

After all, he did have a good job. He did have to report to the studio and he did have to learn his lines. Could he possibly do two jobs well at the same time?

But then he decided as did others such as Bing Crosby, that every star should have a financial pillow to weather bad times. His friend Betty Grable had her Baby-J ranch with seven race horses, three of which, Big Noise, Lau and James Session, have won more $150,000 in prize money. What did Robertson have?

“The answer,” Dale says, “was nothing. So I decided to get me into something just the way all the smart money men have done. I got me into Everlast Laboratories.

“I brought my brother Chet out from Oklahoma, hired my old buddies, and we went to work.” Dale’s factory in West Los Angeles is a fairly large plant. It employs twenty-odd people and it is growing.

One of the employees who prefers to remain nameless, says, “I’ve worked for an awful lot of men in my time, but I’ve never worked for anyone like Dale Robertson. He’s a new breed of boss. You can knock off at three or four in the afternoon. He doesn’t care just so long as the work is done.

“He wants you to get that work done, and if you can do your job in three or four hours that’s fine with him. You’ll do anything for a boss like that. He’s a regular guy. I’m telling you Mr. Robertson is going to be a big success in business. He’s a man of his word. When he tells you something, that’s it.

“He himself keeps strange hours. Comes in ten or ten-thirty; sometimes doesn’t come in at all when he’s working in a movie. But the work gets done.

“He’s got a big office with all the trimmings but I’ve never seen him wear:a tie yet. First president of a company I’ve seen without a tie. Doesn’t mind working with his hands either. He’s loaded the truck. He’s run the canning machinery. He’s done everything.”

How does Dale’s wife, Jacqueline, feel about her husband’s, business venture? The Robertsons still live in a $52-per-month G.I. tract house.

Her friends say that Jackie deserves better. “After all, she was accustomed to a much better standard of living as a single girl. Her father is Sering Dunham Wilson, of the social Philadelphia Wilsons and her mother is Fairy Burney, the actress. Jackie was born in Paris, brought up in Princeton, and sent to private schools.

“I wouldn’t say that she married beneath her, exactly, but I would say that now that Dale is making some good money, he should have moved his family into a more comfortable home. Instead he takes everything and plunges it into this business. After all, he is making a thousand dollars a week. If he were my husband, I’d demand a higher scale of living.”

But Jackie Robertson is not the sort of wife who makes demands.

Her faith in Dale is limitless. He is not an easy man to live with; he tends to be moody, opinionated, and a little spoiled. But Jackie is very much in love with him, and now that she understands what makes him tick, they have made a satisfactory marital adjustment.

Dale Robertson does not come out of the mould that usually makes an actor. He is no self-centered exhibitionist. He is a man who loves the outdoors and a great deal of action. He likes to work with his hands as well as with his mind. He knows his first responsibility is his family.

He likes being an actor but he dreads being a “has-been” actor at forty.

When Rochelle grows up and people ask what her dad does for a living, Dale doesn’t want her to stammer and pause and finally say, “Well, my father used to be a movie star.”

He’d much rather have her say something about the old man not only having been a great movie star, but also president of Everlast Laboratories.

“Reckon that’s why I’m beating out my brains,” he explains, “holding down two jobs at once.”

THE END

BY THELMA McGILL

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE MARCH 1954

No Comments