The Ingrid Bergman In Question

Ingrid Bergman was recently asked to return to Hollywood to star in “Strike a Match.” Since the offer went to her from Howard Hughes, multimillionaire owner of RKO, the matter of money could not have been a stumbling block. Besides, those very brilliant young men, Jerry Wald and Norman Krasna, were to have been in charge of the production, which would have offered Ingrid a role that would have been a veritable sugar plum for an actress of her undisputed talents.

But Ingrid refused this offer and will instead star in a picture her husband Roberto Rossellini will make in France shortly after the first of the year. It’s a year and a half now since Ingrid announced that she was leaving Doctor Peter Lindstrom and that she would marry her director, Roberto Rossellini, as soon as she was free. Six months later, on February 2nd, she had a son, Renato, by Rossellini.

AUDIO BOOK

At this time magazines and newspapers reported on Ingrid in every issue and in the greatest detail. But during the past year little or nothing has been written about her. Which accounts for the tremendous interest in her that exists, currently.

Wherever I went in Europe this year I met motion picture stars—honeymooning, working in the studios and on location and holidaying. And always our talk would turn to Bergman. Was she as happy as she looked in her photographs? Did I think her love for Rossellini would endure? What did my old friend Anna Magnani, who previously played Trilby to Rossellini’s Svengali, have to say on the subject?

“Magnani,” I told them, “has been extraordinarily magnanimous—for Magnani.” For when I had asked Anna how she felt about Ingrid, she had shrugged.

“I have no anger for Madame Bergman,” she had said, “only the very greatest sympathy!”

Currently, it must be reported, Ingrid appears to need sympathy from no one. She is still utterly, completely in love. Rossellini seems to be also. He never leaves her side.

Recently, when they were in Paris together, a friend asked Ingrid, “Is it true you are expecting again?”

“I expect to have many children. I want a large family by Roberto,” Ingrid answered with a smile.

It is difficult, sometimes, to believe that the recklessly romantic Mrs. Roberto Rossellini, by virtue of a proxy marriage in Mexico, is the shy conservative creature we used to know.

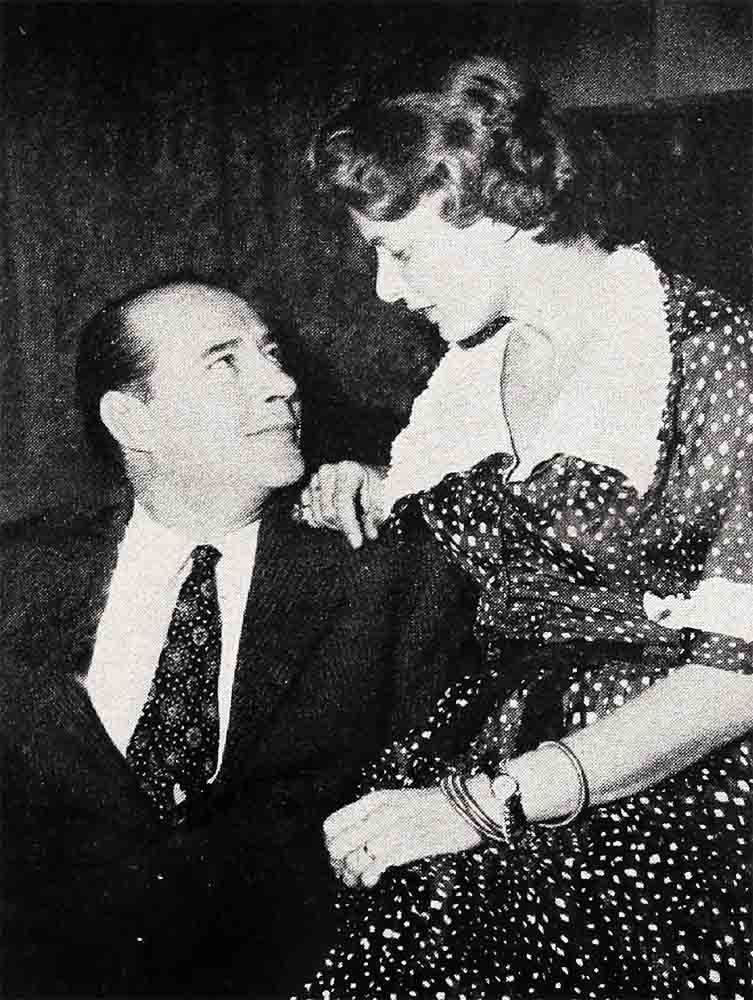

However, I remember so well, about four or five years ago in Hollywood when I visited a studio set on which Ingrid was working. My host, that day, a famous man star, must remain nameless.

When Ingrid left the set his eyes followed her, amused and admiring. “Quite a woman,” he said, “isn’t she?” Then, not waiting for an answer, he went on, “She’s going to find it out one day, too—and when she does, look for trouble.”

“You don’t think she knows it yet?”

He shook his head. “Elsa, you know as well as I do that no woman aware that she’s quite a woman sinks everything she has into a career!”

He was very astute, this actor. But I doubt that even he guessed how completely Ingrid was to kick over the traces.

She was looking for Rossellini, I’m convinced, long before she found him. Quite unconsciously, of course. In fact, when the long run of “Joan of Lorraine” kept her in New York, away from Doctor Peter Lindstrom, and so gave her a true perspective, she asked for a divorce. Lindstrom would not hear of it.

Once she met Rossellini, however, her marriage was over; even though it was to be two years before the California courts or Lindstrom accepted this fact.

In Sweden, you know, any gentleman from the South—an Italian, Frenchman, South American—is certain to be a great favorite with the ladies. The Latin grace and charm and gaiety are a happy contrast to the stolid personalities of Swedish men.

And Roberto Rossellini is an especially attractive Italian. Many things have been said of him. And half of what has been said, at least, is downright damning. But no one denies his tremendous warmth and charm. He is quite able to hold a roomful of people fascinated. Add to this his knowledge of, his success in, and his interest for Ingrid’s own art medium and you will realize how all that happened was like a flood tide.

Ingrid and Roberto are living now in their new home on the Mediterranean. This, as Roberto drives any one of their five cars, is only a few minutes from Rome, nineteen miles away. It is exceedingly well staffed, too, their house, for, including the nurse for their son, Renato, they have ten servants.

This sounds as if the Rossellinis were possessed of great wealth. I’m sure they are not. Otherwise Rossellini would not have refused all the newspapers permission to use photographs of his infant son unless they paid his price—and it was not a modest price—-for the pictures he took of Ingrid and Renato. He has what he earns as a director over there, far less than any Hollywood director’s income. And Ingrid has her percentage rights from “Under Capricorn” and “Joan of Arc,” which she made before she knew Rossellini, and the fateful “Stromboli” which they made together. How much these percentages amount to is anyone’s guess. However, not any one of these three pictures has been a great success. However, in Italy an American dollar goes far, buys a lot of lire.

If “Under Capricorn” and “Joan of Arc” had turned out more successfully we might never have seen the affaire Rossellini. I, for one, have always been convinced that Ingrid turned to him first— having seen the pictures he had made with Anna Magnani—because she believed him to be the great master who could change the unfortunate pattern into which her career was falling.

“Stromboli” of course was the greatest failure of all. Roberto puts the blame for this on the way the film was cut and narrated in America. Ingrid agrees. That Ingrid regrets her statement that she would retire permanently from the screen has long been apparent.

In corroboration of what I say, Ingrid reads her fan mail most carefully. But it is so contradictory that it is impossible to gauge the public pulse by it.

A letter with a Finnish postmark told her, “You have given your nameless son a black eye before he was born. Why don’t you hang yourself? The public is going to get even with you, anyhow.” Only the postscript suggests the correspondent still has Ingrid’s interests at heart. It warns, “Take care of your own money in your own account.”

Contrarily, a woman from Illinois writes: “Every adult with a thinking heart knows you could have easily by-passed your son’s birth with your own secret ‘Hollywood Appendix.’ And each such person knows you are a fine person, torn between your conscience and duty and what must be a very great love.”

Ingrid tried, I think, over and over, to save her marriage. In his divorce testimony Doctor Lindstrom said: “The last thing my wife did before she went to Italy was to select wallpaper for a new nursery in our home. We had been on a vacation to Aspen, Colorado, on which we had made plans for the future. This included a second child.”

How many babies are born, I wonder, because their parents hope to strengthen a marriage that isn’t working out too well. Too many, is my guess.

Later in his testimony the doctor, who charged cruelty and desertion, said that when he arranged his dramatic meeting with Ingrid on a Mediterranean island—while she was making “Stromboli”-—that she promised to change her ways. “She told me, ‘this has to stop,’ ” he said. “She promised she would discontinue the relationship, have nothing more to do with the Italian director outside her profession.”

Here again I believe Ingrid meant what she said—when she said it.

In Stockholm where Peter and Ingrid lived before they came to America there’s no surprise over what has happened. Ingrid’s cousin, Greta Lindahl, who works in the florist shop that her uncle and Ingrid’s uncle owned, said: “Ingrid used to act in this room. Now and then she’d fix lunch for us. Meatballs were her specialty. And, around Christmas, when we were very busy, she’d deliver flowers.”

She went on to report that Ingrid had made her first professional appearance when she had recited poetry in a night club. “Then,” she said, “she went on to the Royal Academy. And, at a party, she met Peter Lindstrom. He was from Stoede, the north of Sweden, where his father was a gardener. The family thought him cold and ambitious.”

In Stockholm also there’s Jules Berman, famous author and journalist and Ingrid’s friend for many years.

“She has developed,” he reports, “and grown into a woman who is no longer afraid of life. ‘Why,’ she asked me when I saw her recently in Paris, ‘should I spend all my life with a man I do not love?’”

With Rossellini, certainly, Ingrid is happy. Besides being evident in all her pictures her happiness runs through her conversation like an electric current. Always she is saying how lovely her baby is. Constantly she is telling of the wonderful things her husband has done. And when Rossellini made his last picture, “Francis, God’s Jester,” she sat with him long hours every day in the cutting room, exactly as she said she would do.

This production, shown at the International Film Festival in Venice but not yet available to American audiences, merited high praise. It is of interest that in it the monks are portrayed by real monks from the Franciscan Monastery of Nacera Inferiore of Naples.

Ingrid has been troubled about many things during the past two years. It couldn’t be otherwise. Above all she has been troubled about her separation from her twelve-year-old daughter, Pia, now renamed Jenny Ann by her father. She has kept in touch with her, however, by letters and gifts and frequent telephone calls. And now that a California divorce has been granted Doctor Lindstrom she will see Jenny Ann every summer.

“What are your plans?” I asked Ingrid a few weeks ago before she had had the Howard Hughes offer.

“I do not have any,” she said. “I cannot make any.”

However, others tell me that, more than once, she has admitted that she would give anything if she could get back to America and make one good picture. But Ingrid, I think, remains dubious about the advisability of returning lest the reception she and Rossellini receive—and she’ll go nowhere without him—might be unpleasant.

A great deal has been said about Ingrid during these last few years. But it remained for Peter Lindstrom to do far and away the best job of summing up.

When he was on the stand and his attorney asked, “Do you have any bitterness towards her?” Lindstrom hesitated, then answered, “No. I feel sympathy for the predicament she has placed herself in. But I think she has many good qualities, besides being very beautiful.”

The future remains uncertain.

But currently, I think, Ingrid, for all of her problems—her deep concern over public opinion, her loneliness for her daughter, her absence from the studios—is happier than she ever was before in her entire life.

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE FEBRUARY 1951

AUDIO BOOK