Charles Coburn—The Monocled Cupid

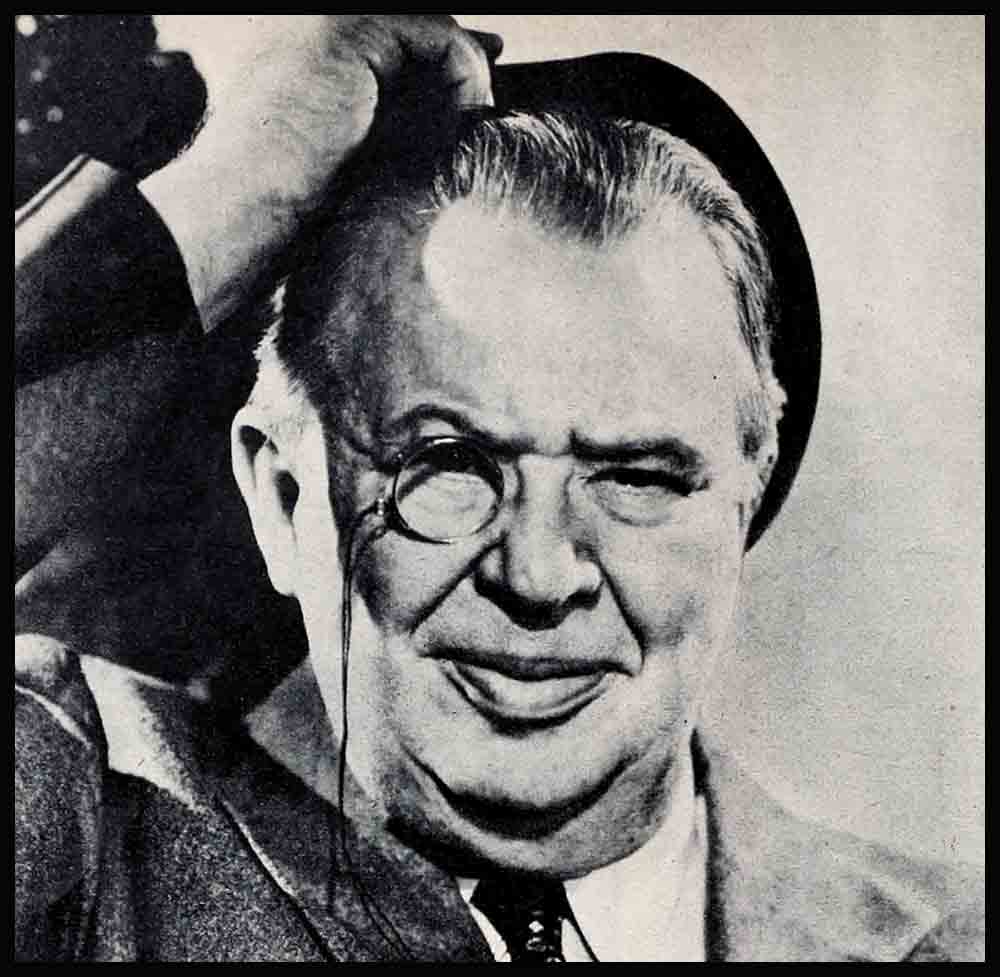

Charles Coburn is the distinguished gent under the monocle, the chins, the corpulence and the balding mane who canters about the Hollywood sound stages filching pictures away from pin-up queens and leading men with wavy hair. Without a dimple in his chin he makes as much as Cary Grant— something like $7500 every Thursday. Without a trick nose or an elbow-bender’s following, he gets more laughs per square foot than W. C. Fields and Jimmie Durante combined and without a tonsil tremolo he has almost as many bobby-soxed darlings rooting for him as Sinatra.

How does he do it? It’s no secret—especially to Coburn. He’s an acting gem, he admits, and he says there should be more like him. Thus, he spends his off-time worrying about the State of the cinema when the old boys like him die off, one by one. “Where will they get actors to replace us?” he grieves. “How will sweater girls be able to carry their own pictures?”

Coburn’s sixty-six, a widower, a cigar-smoker—and the No. 1 dream man of the after-forties. His dream-man status was decisively established when the picture, “The More The Merrier” was exposed and subsequently won him the Academy Award for 1944. The star, Jean Arthur (who’s plenty cute), and costar, Joel McCrea (who’s plenty handsome), sat back and understood when the phrase-makers keynoted the film with “This is the only picture with a ‘dingle’ in it.”—Dingle, of course, being Charles Coburn.

He does it again in “The Impatient Years,” climaxing a career in pictures that began with “Of Human Hearts,” continuing with “Vivacious Lady,” “The Devil And Miss Jones,” “The Constant Nymph,” “Heaven Can Wait,” “Princess O’Rourke” and “Wilson.” About twenty other hits carry the in-between sag. He’s played comedy, in the main, but he can do heavier things, too, “like ‘King’s Row’,” he offers, “in which I cut up a lot of nice people in the name of the medical profession. That’s ‘heavy,’ isn’t it?”

His versatility, which lets him range from the humorous to the homicidal, is again chalked up to that acting virus lodged in his intestines. “A great actor can play anything,” he bellows, smugly. Then, bowing to the Dingle tingle,he stage-whispers: “And great parts make great actors.”

Coburn’s agent is a youngish chap named Irving Salkow, who was once a child extra in Cobum’s “Merchant Of Venice” on Broadway. Irving, hungry for blood even then, decided to make his walk-on a stand-out and when the extras were cued to throw old shoes and bottles at Cobum (playing Shylock), Salkow heaved his prop boot squarely at Coburn’s reciting noggin. Shylock reeled—but recovered in time to fire Salkow before the evening show. So Irving grew up to be Charley’s ever-loving ten-percenter, collects close to a thousand dollars a week for the privilege—and the two of them go to prize fights, horse races and night clubs together. Strange chums—an actor and his agent!

When Salkow first started to peddle the Coburn talents to the picture makers, most of them put their fingers to their noses, swore “Shakespearean actors equal ham,” and let the guy get out with his top teeth still intact. And since Coburn was going great on Broadway with his own repertory company nobody cared whether or not the fine old fellow ever saw the inside of the Vine Street Derby.

Nobody, that is—but Salkow. He, poor thing, cared enough to make a couple of trips back to New York to work up interest from Coburn, then back to Hollywood to do the same thing with the producers. Finally, Metro bogged down under the Salkow pounding and said, all right, maybe the old fox might be good as Judge Hardy in a new series they were starting.

Wonderful, marvelous—but now Coburn didn’t want to play! “No long-term contracts,” he insisted, holding up the paling Salkow at the same time. “I’ll come out for one picture—but just one at a time.”

The Coburn-Judge Hardy test was eventually run off when the casting of “Of Human Hearts” began. A few hours later Charley had won the Dr. Shingle part right out from under Lewis Stone’s fatherly expression—and Stone was resentenced to life among the Hardys. Coburn, meantime, has surged forward—chins, monocle and all—to lute our attention away from legs and bathing suits over to age and heft. Not too easy a job, especially with the army-camp trade.

Coburn’s not English—surprise—he’s southern-fried, from Savannah, Georgia. Comes from a family of musicians and college professors and soon as he was old enough to grow top hair he decided he’d be an actor. He began at thirteen as a program boy at the Savannah Theater, worked his way up to manager—at eighteen. During his reign, all the great theatrical stars played Savannah—among them, Modjeska, Ellen Terry, Joe Jefferson and Henry Irving.

A personal—but very pleasant—brush with the great Irving himself made Charles determine to launch his acting career. So he announced to his family that he was going to New York. He had some lean days. He did a little bit of everything—riding bicycles in marathons and wrapping parcels in Altman’s basement. Finally though he got a chance to sing baritone with a Wisconsin light opera company. It was small but it was a beginning. He talked (and sang) his way into the New York big time, into road shows, Shakespearean revivals.

In Nashville, he and a girl named Ivah Wills played Orlando and Rosalind to each other and decided the rumblings they felt in the big wreath-planting scene must be love. Before the company pulled out of Nashville, Ivah and Charley became Mr. and Mrs., kept it that way for thirty-three years, managed, produced and acted in their own companies, and came out with hits like “The Bronx Express,” “The Better ’Ole,” “Doll’s House” and most of Mr. Shakespeare’s sadder sallies.

Summers the Coburns took over the Mohawk Drama Festival at Union College, taught kids how to be woodland nymphs and Romeos and proceeded to wallow in the stuff—until Mrs. Coburn died. This was in 1937. Now, Salkow decided, would be the time for Coburn to come to Hollywood and stay a while. Work, lots of it, was the antidote for his severe loss. And this time when Coburn came to Hollywood he decided to stay long enough to make the beautiful boys sorry they weren’t sixty-six (the draft notwithstanding).

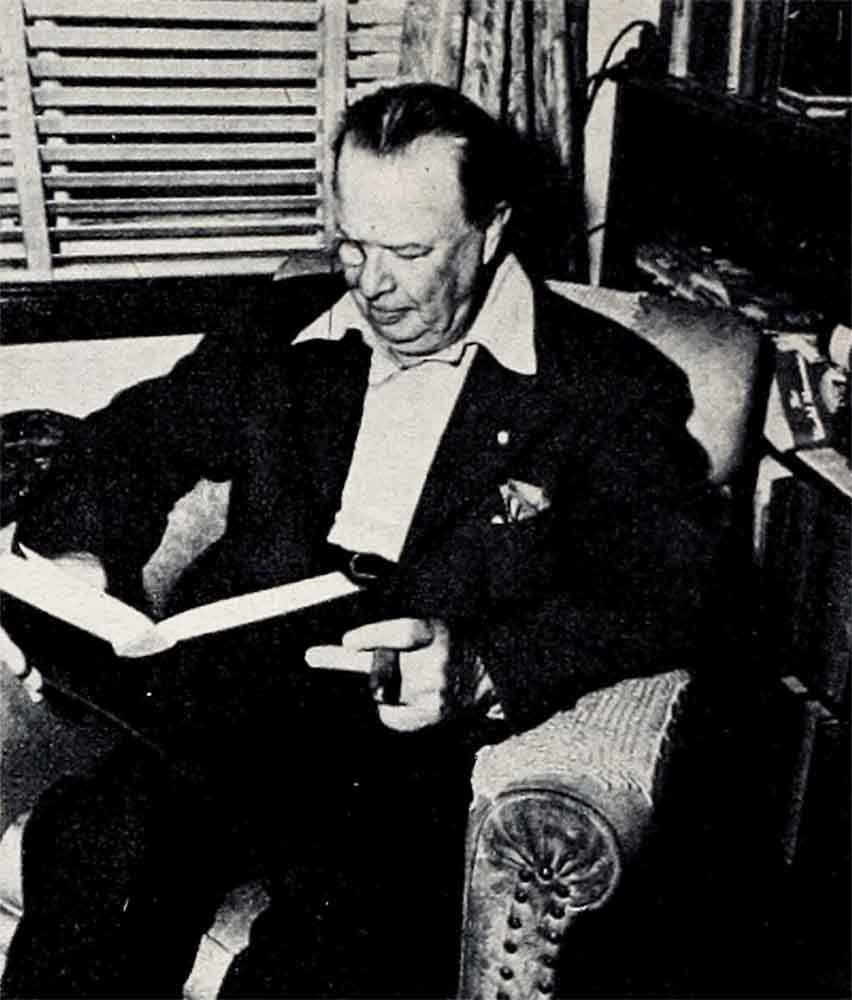

Charley’s home is still Gramercy Park New York, but in Hollywood it’s a five-room arrangement in an apartment house next door to Ciro’s. To lick that “on tour” feeling he’s got his Confederate flag around, his pictures of Ivah and Henry Irving and a shot of himself on a bicycle showing his eighteen-year-old legs. “I don’t exercise now,” he says, shrugging over the bike pose. “I did all that before I was forty so I wouldn’t have to bother now.”

But he hasn’t given up night clubs on pretty girls. He still swings a wicked rhumba with Anne Shirley or Jean Arthur and hugs Olivia de Havilland in the middle of the Mocambo dance floor.

When there’s a letup in the gal excitement, Coburn sleeps. On the set, at the Friday-night prize fights, at dinner parties—anywhere. His delight is sleeping during lulls in the conversation, or between short breaks in production.

But he’s not asleep when there’s a cupid job to do—and that’s exactly what he’s doing with his role as Jonathan Crandall, Sr. in “Together Again”—playing cupid for Irene Dunne and Charles Boyer. And doing a great job of it too!

That’s one thing you can bet on—Charles Coburn will always do a great job of everything—even sleeping!

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JANUARY 1945