Mad About The “Boys”—Piper Laurie

At tea time Piper Laurie was drinking tea. In Hollywood this is considered rather fey conduct, even in the British colony, but Miss Laurie likes the stuff. She was drinking tea and talking about men—she likes that stuff, too. At twenty-two, Miss Laurie might even be considered a connoisseur. Her preference for tea was by way of a guarantee that there never will be a pied Piper, which may or may not be a joke. Miss Laurie was moved to laugh slightly.

“You spoke of older men?” she said, making it sound like a question. “What do you mean by older men? Older than whom?”

Never mind. What was Piper’s definition of older men? What, for example, would be call middle-aged?

“Over sixty,” said Miss Piper, “for most men. Not until ninety for a few. And for one or two, never! Some have that wonderful ageless quality. But I never think of age in relation to men anyway. Or not much. It’s the men themselves that count.”

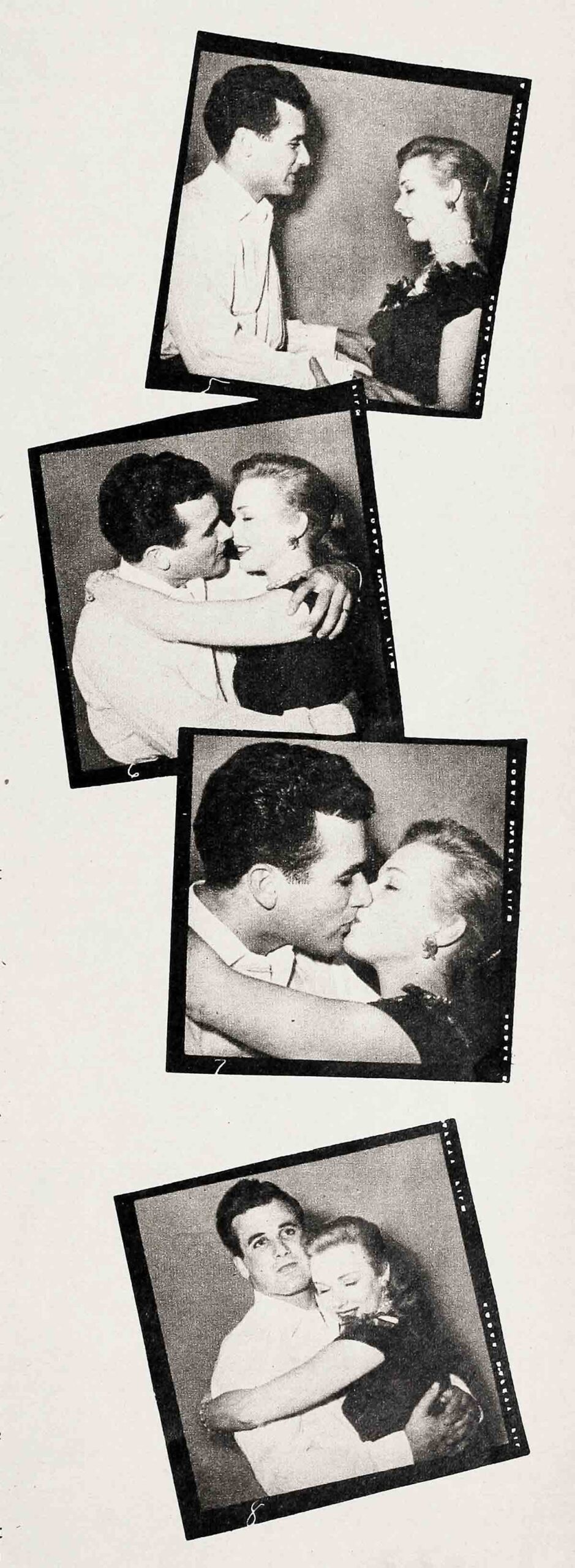

That had a fairly profound ring. Would Miss Laurie go on? The background is that she dates both older men—Producer Leonard Goldstein being a notable case in point—and younger men—among whom it is fairly safe to cite Dick Contino, despite reports that the two have shed one another over a little matter of who works and who doesn’t. Not so. But it probably is so that Contino and Piper have never discussed marriage.

“I’m not going to marry Dick,” said Piper, with what night be termed firmness. “I’m not going to marry Leonard. I’m not going to marry anybody. Not yet. My work comes first. And if I cross you up by doing it before your story “comes out, I’ll apologize in the public square. But you don’t have to worry about it.”

Well and good. Back to men.

“All right. But only if we leave words like ‘middle-aged’ out of it. I think every girl should know older men, even go with them, before she sails into marriage with a man her own age. And I certainly don’t see any reason why she shouldn’t marry one if she happens to love him. Older men have a great deal to offer that the younger ones don’t have. That’s not hooting down my own generation. I guess I’ve made it clear I like them all ages. But the age isn’t the factor. It’s the individual.

“Now I go-out with an older man—let’s ‘say forty—and he has a tolerance a younger one might not have. His years are in his favor that way because he’s apt to be more polished and more courteous and—well, every bit as interesting conversationally. To say the least.

“I don’t mean in a high-brow sense. And I don’t mean young men are dull. But it simply figures that the man who’s lived longer has more to say and is better equipped to say it. Of course you might have more in common with a boy your own age. But a girl should grow, too, and shell grow by learning, and she learns from her—well, seniors.”

Piper had expressed a universal fondness for the male sex. It is not to be construed from this that she is indiscriminate. On the contrary, she is discriminate as all get out. That’s easy to spot. She’s a red-haired party with perfect skin and exceptionally delicate, sensitive features.

“You see,” she said, “there are so many small things a man should learn if he hasn’t. There are so many small ways to embarrass a girl. And other girls will know what I mean. For instance, there was this man I used to date—he was fortyish—and on one of our first evenings out, he parked the car in a restaurant lot, got out and just headed for the entrance. And there I was, waiting for him to open the door for me on my side. I hadn’t realized he wasn’t going to, or I would have opened it myself to save him embarrassment. But I waited a few moments too long, and he was coming back while I was opening it. It sounds like a small thing, as I say, and it was a small thing—except that it spoiled the whole evening. He had been made overly conscious of a slight slip, and I was the one who’d made him conscious of it. We both lost a little that evening. But always after that, he was much more courteous in the—you know, trivial ways—so it worked out all right in the end. But he was insensitive to-begin with and I don’t think girls like that, not that I’m setting myself up as a spokesman for American womanhood, but I don’t. If I were writing a manual for escorts, it would be full of things like opening doors, seating your dinner partner and not stranding her in a crowded room. But what was funny about this episode was that he was an older man.”

Had Piper any occupational preferences—in escorts, that is? She has dated actors, students and other non-professionals. Before her much-publicized attachment to Contino and her steady companionship with Goldstein, she had gone with Rock Hudson, George Nader, Vic Damone and independent producer Frank P. Rosenberg, a man of forty by now.

“No. No preference. Only in men. Of course, actors can be a lot of fun. It’s a natural part of their make-up. I don’t like a man to be too much of a sobersides, but even there, it depends on the person.

“I’m afraid of generalities and I can’t be pinned down on an idea. There are too many ifs, maybes and on-the-other-hands.”

Not even on so safe a topic as Hollywood wolves? Seems a girl couldn’t make an error decrying these.

Piper laughed—an agreeable sound. “There are wolves and wolves. I’ve thought some of itemizing them. There’s the one with the brotherly approach, just two kids together out for fun and laughs. Oh, so platonic! Only by and by it turns out that isn’t entirely what he had in mind. That one’s a sneak, I’d say. Even the forthright wolf is better and the forthright wolf is the most insensitive male there is. The older ones may warn you of the snares a young girl is subject to, without bothering to mention they’re one of the snares. Then there’s the wolf who doesn’t care how much he throws the word love around, as if it were a volley-ball, and that’s pretty disgusting. Need I go on?”

Thank you, no. Instead, could we return to the subject of Mr. Contino?

“Dick? What can I say? Dick—Dick has a lot of living to do, a lot to make up. The lost years and—well, you know.” Contino, for the benefit of those who have been residing in Tibet, was jailed for draft evasion but later served honorably in the Army in Korea. He’s paid up in full. Also for the Tibetan annex, he is a very highly paid and able accordionist. “People never knew the whole story of what happened to Dick—what was behind it all. I don’t mean politics or anything like that, but if they knew it as well as I do, they’d be a lot slower to blame him. Anyway, it’s done now and behind him, and I don’t think the American people are going to want him punished any more. He’s living it up now, and I don’t blame him.”

And Mr. Goldstein?

“We’re just good friends,” said Piper, producing the laugh again. “The Hollywood press would save itself a lot of trouble if they had a rubber stamp made of those words.”

Piper hadn’t been giving her contemporaries much of a shake up to now. Wasn’t there something to be said for young males as well?

“But certainly!” cried Miss L., getting quite a lot of zip behind it. “Haven’t I made that clear? Men are just wonderful—younger men, older men! Except for the ones that aren’t. Some of my best friends aren’t a jot over twenty-four. They aren’t entirely mature yet, but then neither am I. And I guess that’s what I like about them. It’s a matter of occasion, too. For the concert or the theatre or dinner, perhaps, an older man might fit the bill better. But dancing or hiking or just a general fun party, you like people your own age. To tell you the truth, I don’t know many men over thirty-five that I’d risk on a hike. They’re all right when the going’s level, but when you start uphill you leave ’em. And I’m an uphill hiker from way back.”

Still and all, though, the young ’uns were prone to be less courteous?

“Usually. In the small things, remember. Not always. Here’s another example of what girls don’t like—and this was an older man, too. He took me—I forget, but it was some banquet downtown in a hotel. We came in through the bar. It was jammed. But instead of staying with me and helping me through the crowd, he just plowed on ahead like some kind of halfback. I couldn’t move. Finally I got mad and just stood still. He was all the way to the dining room entrance before he missed me. Then he came back. And there was another evening half-ruined, because he’d been thoughtless and I’d made him realize it. Not that it ruined our friendship or anything like that, because it didn’t. Maybe in the long run it did some good. But I’m not glad it happened. I repeat, men are just wonderful—but the little things, the little things, the little things!”

Piper’s protestations to the contrary, half of Hollywood would not be surprised if she married Contino in the near future, meeting in the process his alleged demands that she confine her energies to being Mrs. C. and nothing else. The other half of Hollywood thinks it can’t happen. This is the half that is dead convinced, correctly or otherwise, that Piper is a careerist before she is anything and that no trifling interloper such as love is going to derail her progress. It has been pointed out that she’s had some mighty handsome matrimonial offers, and that nothing has come of them. Yet there is something wrong with the type-casting of this particular’ beauty as an inflexible careerist. She is small with a bell-like voice, almost wholly unassertive in casual conversation and professes no far-flung ambitions beyond an urge to be a better actress.

“For two or even three years I want to go on with my profession, grow as a—oh, there must be some better word than ‘artist’—well, as an actress. After that, I just couldn’t make a prediction. But right now I’m definitely not in love and I’m definitely not getting married.”

The legend that Rosetta Jacobs, to give our heroine her proper handle, places the career of Piper Laurie above every other consideration may have its roots in one of several circumstances.

One is the amazing information that while still in grammar school this wunderkind wrote, produced and directed quite a few complete plays. Single-mindedness may be evidenced here.

Another is the testimony of a fellow player—not one of Piper’s most devout rooters—that she can be a pretty dynamic personality when crossed unfairly.

A third is a matter of common information: between acting bouts, she likes most to act. That is true. After one take of a picture is made and while she’s waiting for the next, this tireless mime dragoons fellow-members of the company into running through scenes from other pictures or from some totally unrelated play. Strictly for fun. Thus it cannot be said Piper doesn’t know what she likes best to do.

Still, it is hard to envisage her as an unbending careerist, subject to no distractions in the way of amour or anything else. The steely set of the jaw is missing—and there is nothing peremptory in her regard for the male animal.

Piper is a Detroit girl of Polish and Russian extraction who moved to Los Angeles in time for high school, and thereafter latched on to pictures in practically no time. She was seventeen when Universal-International signed her, and eight months after that she was playing a lead opposite Tony Curtis in a number titled The Prince Who Was A Thief.

The picture remains and will forever remain the most memorable for Piper because it was her first. Some say it also whetted her appetite for fame to its present alleged dimensions. Piper says it’s artistic fruition she wants. And it is only fair to point out that she ought to know.

Well, after The Prince, a pretty big deal of another sort took place, one over which Piper is still beaming. Los Angeles High School, at which she was a very bright student, never had seen its way clear to casting her in one of its plays. Now her doting alma mater invited her back for the unequivocal purpose of honoring her as an actress. That for the LAHS drama beagles!

And that for three other major studios as well; not one, before U-I, had let her through the front gate more than once, each time for unsuccessful interviews.

Piper first came to national attention, though, not via the screen but by dining on camellias. There happened to be a cameraman present and the picture got rather wide distribution. Camellia-nibblers are uncommon except in the minds of publicists, where they are a dime a dozen, but other people were startled.

But to put this forward as still another proof of over-weening ambition is silly. Camellias don’t taste bad, and besides she didn’t eat the whole thing.

Except for this mild eccentricty and the drinking-of-tea-at-teatime, Piper is not a bit different from any other American girl who bumps maybe a bit more than a thousand dollars a week and looks like a prospector’s mirage. She likes small parties, simple, tailored suits, peasant garb in summer, younger men, older men, in-between men, and strapless gowns for evening. She’s a pretty fair hand with both oil painting and sketching in charcoal, and riding and swimming seem to her almost as much fun as walking uphill. She’s a rather droll little character, too. Says funny things in that wisp of a voice.

Universal figures she’s going a long, long way, and so, according to the poll, do the readers of this magazine. It is not simply a point of beauty, according to the studio’s sharper judgment, but a quality that seems to detach her from a more or less mundane earth. One U-I attaché, not given to high-flown prose, has observed that she is not unlike a camellia herself.

“It’s strange to me,” said Miss L. now dunking the tea-bag a last time, “that anyone sees anything contradictory in my going with both Leonard and Dick. Or strange. Or why they say I’ve switched from Leonard to Dick, or the other way around. It’s not a gap between a young man and an older man. They are simply two separate and distinct persons, and that’s how I think of them.

“If you want to generalize—and you know I don’t—you might say a young man’s a little more possessive or dictatorial, the older man mellower and more tolerant. But there you’re in trouble, because how can you do it without specifying? Which young man? What older man?

You have to give me names. These rules of thumb don’t work. I mean, they don’t necessarily work. It’s like saying, ‘Youth calls to youth.’ Not always, by any means. I have seen youths and youths with not so much as a whisper between them. There are individuals and that’s all there are, so far as I’m concerned. Quote me no general quotes, please.”

The last word on the Contino deal was “that Piper is very strong with Dick’s grandmother. This good lady, who by all accounts is a superb cook, had called from San Francisco a few hours before tea time and asked her up there for a bowl of spaghetti—spaghetti Contino, that is, which is something rather special.

Piper was thinking of making the trip.

And if Dick happened to be up there at the same time, what of that? Something suspicious about a boy’s being with his grandmother? You’d like to make something of it?

Pardon. Contino’s not a boy, he’s a man. And men are just wonderful. You heard the lady. And as for so-called age, what’s that? A state of mind—and a state of mind not shared by Piper Laurie.

THE END

—BY JOHN MAYNARD

(Piper Laurie is soon to be seen in U-I’s Dawn At Socorro.)

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE AUGUST 1954