The Lady Said “Yes”—Robert Taylor & Ursula Thiess

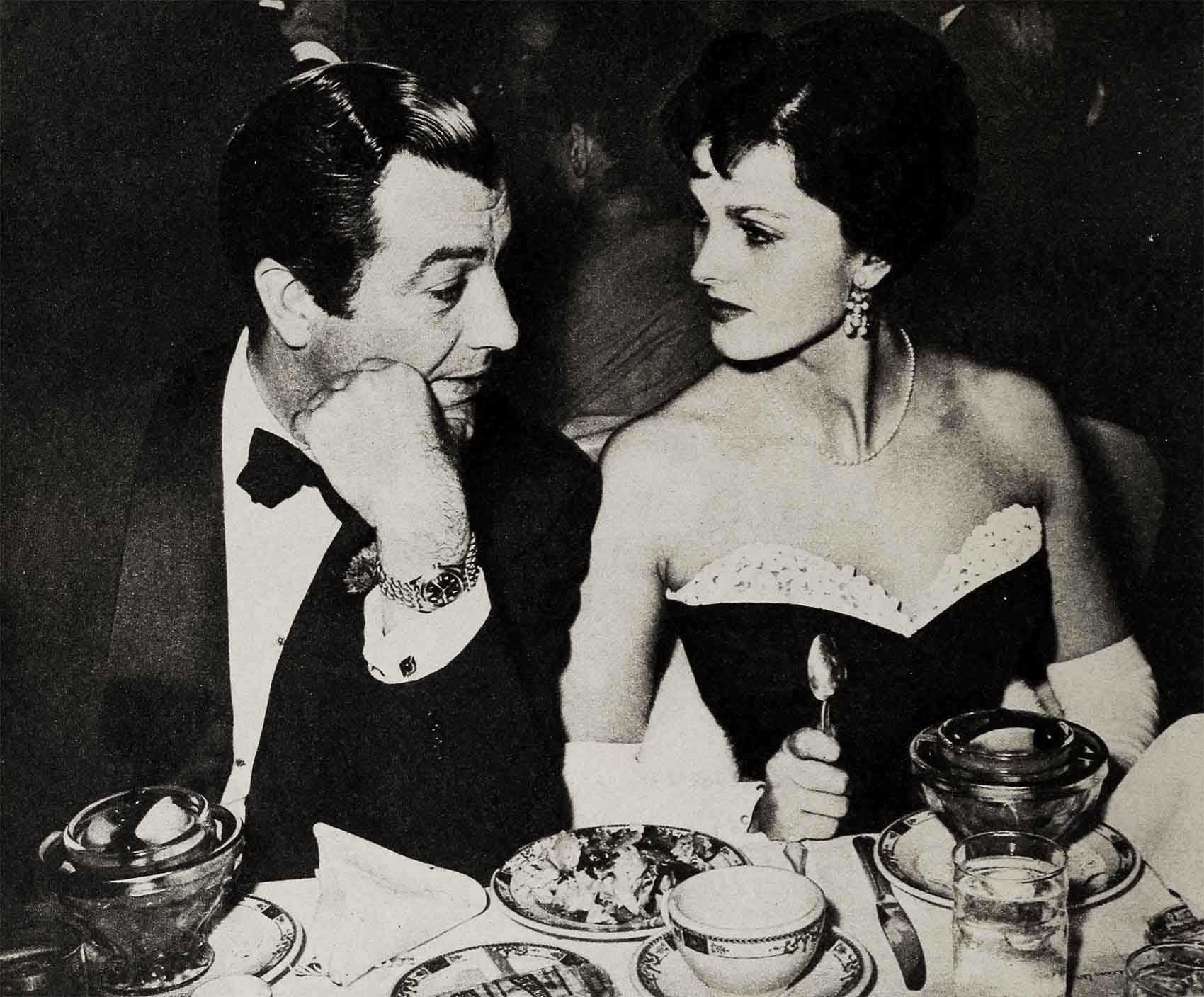

We won’t keep you in suspense or withhold information. This is how they happened to get married. On the twenty-fifth of May, 1954, Ursula Thiess and her fiancé, Bob Taylor, boarded a cabin cruiser on Jackson Lake, Wyoming. They were, they said, en route to location for the MGM film, Many Rivers To Cross. No one paid much attention. When, however, Ursula Thiess disembarked, she was accompanied by her husband, Bob Taylor—whose astounded, completely surprised press agent and studio were paying a great deal of attention.

The exact date was a shock—but many people had surmised that the marriage would take place soon. All they knew for sure, however, was the story of the proposal. It went like this:

On the early evening of Thursday, April 29, Robert Taylor knocked off work on Rogue Cop, went to the telephone on the set, and called his dear and close friend Ursula Thiess, the German actress to whom he had been so long devoted. He would like, he said, to call on her that night.

Miss Thiess, who had been just as devoted to Taylor for just as long a time, acquiesced, but evidently with no intimation of what was coming.

Taylor arrived about eight o’clock, and they used up a few hours talking of whatever he and Miss Thiess talk about—themselves, certainly—and perhaps of her daughter, eight-year-old Manuela, who lives with her in Hollywood, and of her son and her mother, both of whom still are in Germany but will come here as soon as immigration authorities can clear them.

Then precisely at eleven-thirty—according to unusually reliable sources—Bob asked Ursula a question he had been some time getting around to. The exact German equivalent is not available, but in American it goes: “Will you marry me?” At the same time, he produced a ring.

Hollywood, as well as a large part of the rest of the civilized world, had been wondering for quite a spell when Bob and Ursula were going to get this show on the road. Some even were making book on it, pro or con and name your own odds.

Until then, the closest Taylor had come yo to conceding anything was when he told MODERN SCREEN, three weeks before the announcement, the following, in reply to a direct query:

“That question has a familiar ring. I’ll say this much, though. The lady’s name is pronounced ‘Teece.’ You muffed it. I’ll also say we are keeping company. And I don’t mind telling you she was with me yesterday when I bought some Adler silverware. I figure it’s time I began keeping a hope chest. Furthermore, I instructed that the monogram ‘T’ be put on the silverware. I’ll even go this far; I’m house-hunting, sometimes as many as three and four houses a day, and sometimes Miss Thiess is with me. You may now conjecture your head off.”

But the need for conjecture is over. Miss Thiess and Mr. Taylor are married and the marriage has changed many things for Bob Taylor, as such happenings are wont to do. But one strange and spurious supposition about him, it has failed to dent—and this is the peculiar notion that Robert Taylor, married or not, is the loneliest man in Hollywood.

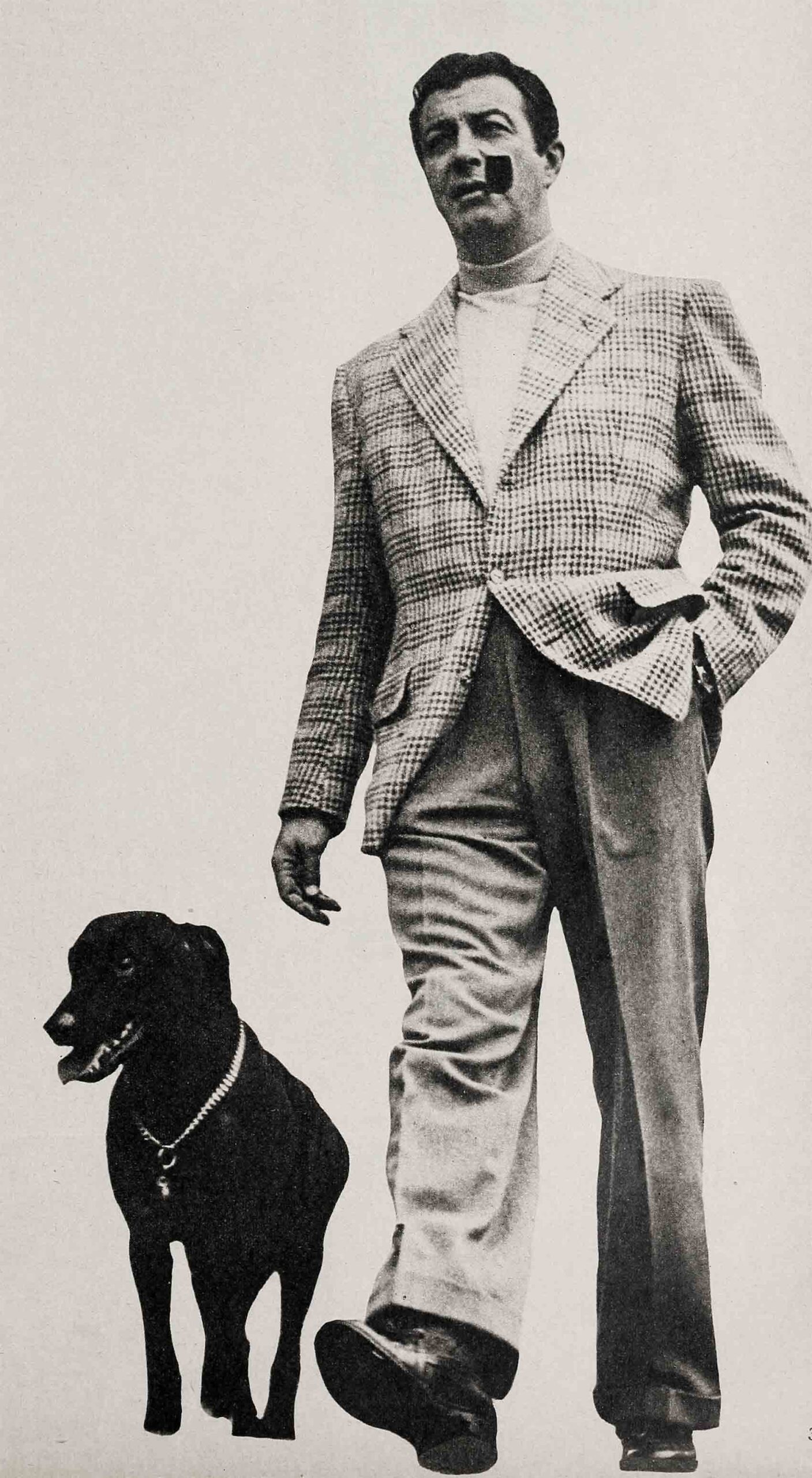

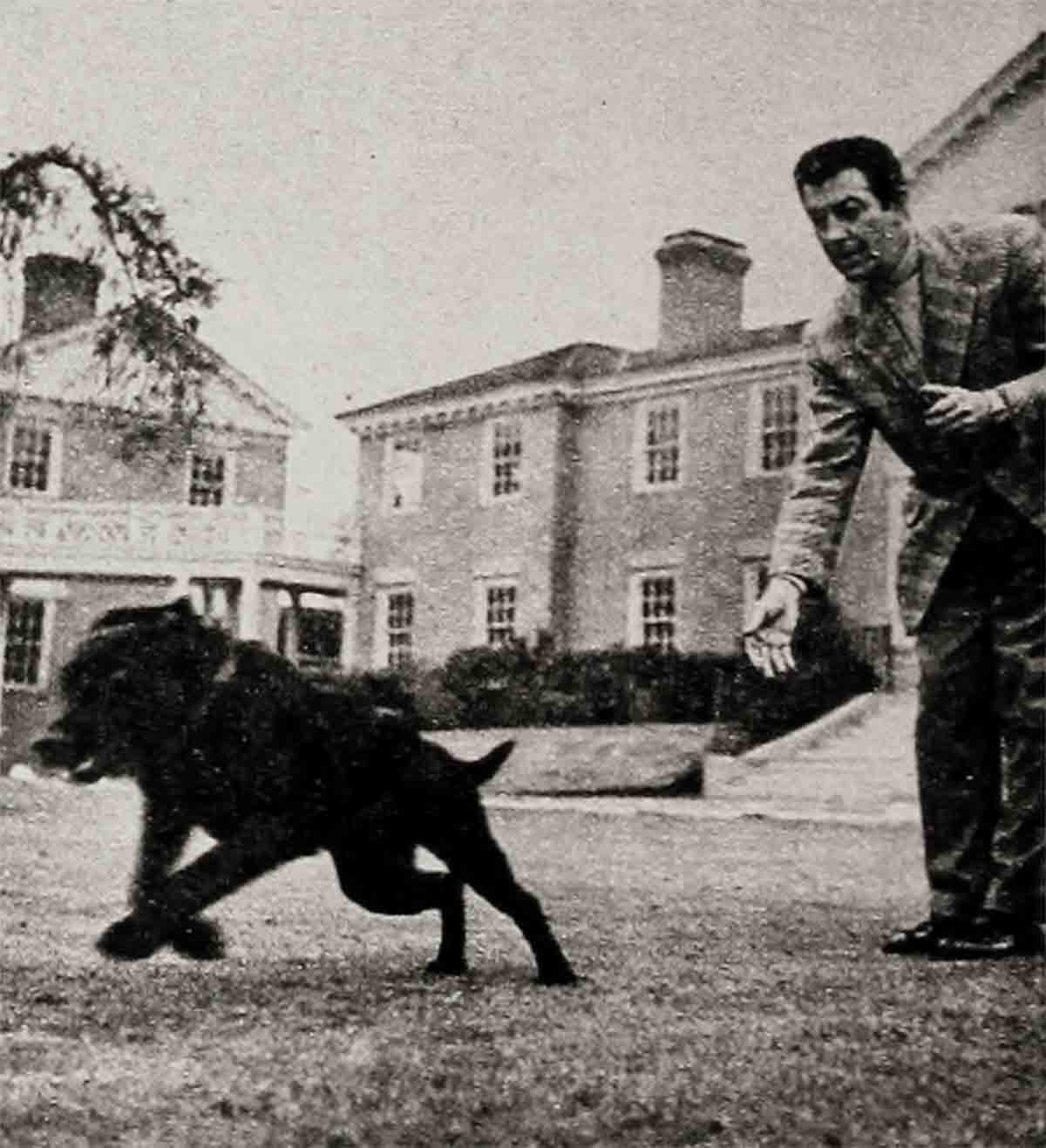

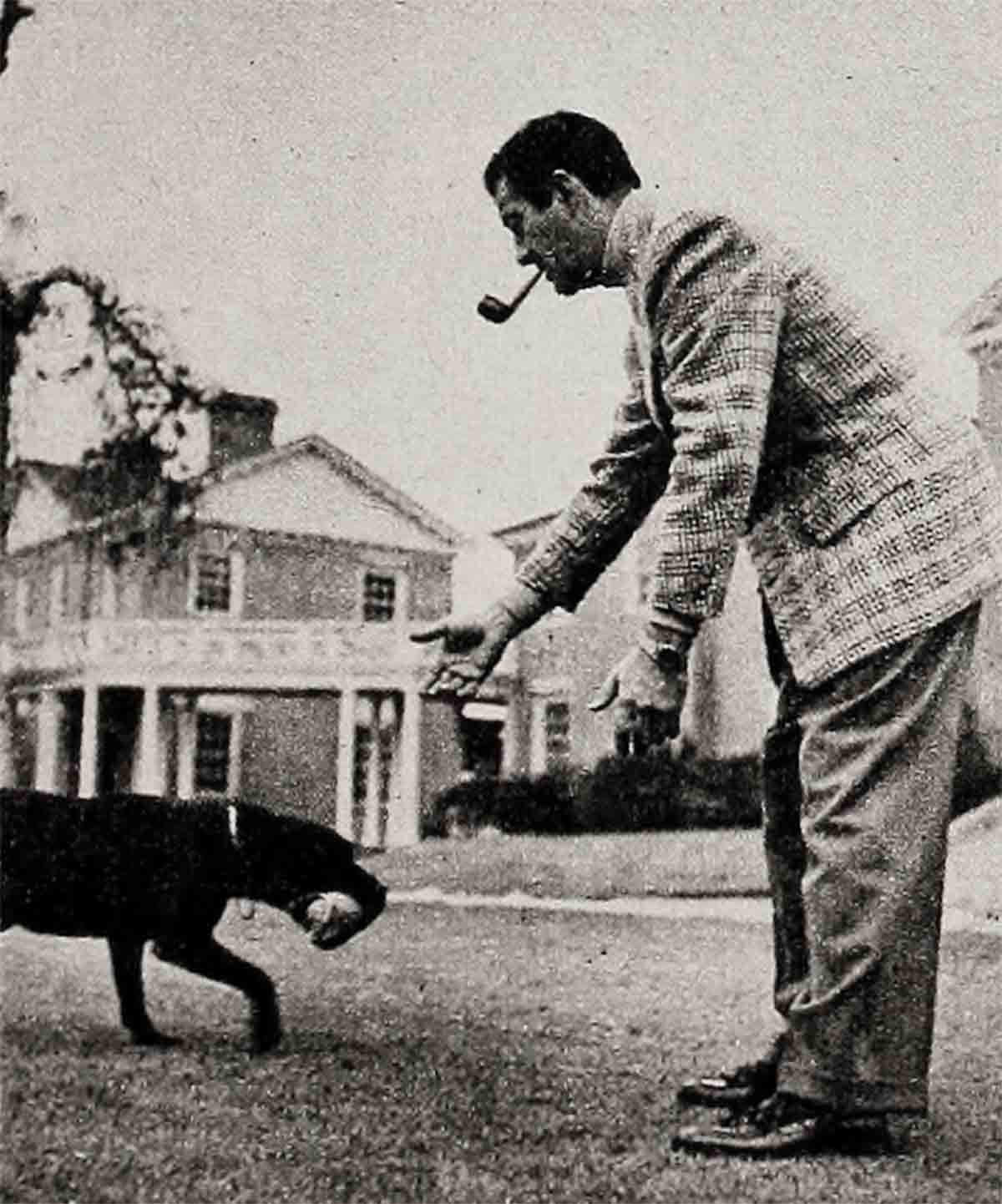

“I DON’T LIKE PARTIES,” BOB ADMITS, PREFERS SOLITARY SPORTS HE CAN ENJOY WITH IS DOG OR WITH VERY CLOSE FRIENDS

He may never shake that delusion.

For Bob Taylor once explained to the press, “I never go anywhere because nobody asks me anywhere.”

Repercussions from this indiscreet—and endearing—bit of personal information have plagued him ever since.

“I keep reading,” he said, “that I’m the loneliest guy in Hollywood. If I read it five more times, maybe I’ll begin to believe it. Then I could have a hell of a time wallowing around in self-pity, except I’m not given to self-pity.

“The picture I get from it is Taylor slumped in his cell-like room night after night, surrounded by bats. That’s interesting but inaccurate. I don’t slump, my room isn’t cell-like and I don’t keep bats. In fact, I lead what I consider a very happy life, by which I mean a life that suits Taylor fine. But if I say that, the weepers insist I’m just keeping a stiff upper lip or whistling past the graveyard. It seems almost impossible for a naturally rather solitary person to convince the joiners that he’s happy the way he is. But anyone like me—and I’ll bet there are plenty—knows exactly what I’m talking about. You don’t have to feel sorry for us. We don’t feel sorry for ourselves. We like it.”

Briefly, Taylor’s allegedly monastic existence runs like this: He has few close friends directly connected with the motion picture industry, but a fair number of convivial acquaintances away from it. He likes small gatherings where people sit on the floor and talk about the best ways to pot a Texas quail. Aside from golf (he’s just taken it up and is not promising) he prefers the more solitary diversions—hunting, fishing, riding, flying. He is delighted with his freedom to go where he likes when he likes as he likes unless his work interferes.

“As, I say,” he went on after a moment, “this ‘lonely’ business began when I told that columnist I didn’t go to any parties because I wasn’t invited to any. Well, that’s not strictly the truth, but for her purposes it was, and I guess for years as well, so I’ll repeat it. I don’t go to any parties because I’m not invited to any.

“But you have to understand that in Hollywood, a party is not a party unless it’s one of those where—what is it they always. say?—‘Everybody who is anybody was there!’ What a crus See thing it must be to 159,890,000 Americans to learn that they’re not anybody! I think we should all band together to make up a mutual sympathy club. No, I’m not invited to those. I don’t know any special reason. Oh, maybe if somebody like Jack Warner were giving a super soirée, he might include me, but I’d be an afterthought.

“Usually, I just read about them in the papers and try not to lose sleep over it. You understand I’m not crying. Unruffled, even—that’s me. I’m just stating a fact. Only thing you might say about it is this (and I’m not sure even here I’m speaking the truth): maybe I don’t want to go to the parties, but I’d like to be invited. Maybe. But you can’t have one without the other, they tell me, and then I’d be in a fix. The social whirl. And what does that do to my freedom?”

Apparently, to Taylor’s way of thinking, that makes him a prisoner of the RSVP set. You can’t fly to Jackson Hole, Wyoming, because you’re due at Brenda Gushberry’s for cocktails. If you don’t show, Brenda positively will never ask you again, and where does that leave you?

“In Jackson Hole, Wyoming,” said Taylor. “And a very nice place to be, too. For me, I mean. For Taylor. Don’t think I’m running down party-goers because I’m not. Start carping at another person’s way of life Just because it doesn’t suit you, and you’re not being what you’d call tolerant.

“But this ‘lonely’ bit—that baffles me. It has a pathetic sound to it, doesn’t it? And I’m one of the least pathetic characters I know. It’s as if I were to point to my opposite number and say, ‘Poor Joe, always surrounded by people,’ and then wipe a tear from my eye. Maybe he looks as pathetic to me as I look to him, but I try not to say so. It could be I think he’s trapped and within himself more lonely than I—and all the people like me—less inner resource, you know. Or maybe that’s not the case. But I wouldn’t.want to stick my finger in his eye, and out of reciprocal courtesy I’d thank him not to pity me.”

Well, that’s the root of Taylor’s philosophy. Friends contend there are external circumstances, too, that limit his appearances these days at the gatherings attended by everybody who is anybody. Of course, for a long time before his first marriage he was in that state of being known in Hollywood, as in Chillicothe, as “out of circulation.”

Both before that marriage and after it ended, Taylor was in great demand. There are less presentable specimens to be sure. When he narrowed his courting range to Miss Thiess, he became non-eligible for the stag-line. Taylor, by fervent testimony of those who know him best, is an impeccable escort; courteous, engaging, non-assertive and postively not the one to stalk his date from Cadillac ambush. This is offered in refutation to those who have Heard It On Good Authority that a girl could do worse than wear track shoes in his company.

It so happens that Bob Taylor, having been around long and successfully, is capable of urbane indifference toward what is mouthed about him—urbane indifference, but not callousness, a state of skin no star can afford.

He may have winced from time to time. After the collapse of his eleven-year—and supposedly idyllic—marriage to Barbara Stanwyck, there were those who said Miss Stanwyck was bitterly angry, whereas Taylor wished to make it the chummiest of divorces. Unhappily for Taylor, Miss Stanwyck was among those who said it: For at least a year, she had no wish to speak to her erstwhile mate. And that agitated a tongue or two. There was talk, as there had to be talk, about Taylor and a girl in Rome, about Taylor and a girl in Palm Springs, about Taylor’s alleged wolfishness that heretofore no one seemed to have noted. Taylor ‘gracefully kept his mouth shut.

It is suspected by some that Taylor’s extraordinary looks are a key to his personality. He is a diffident man, absolutely unwilling to thrust himself forward in any company, and despite his refusal to worry about it, may on occasion rest on a shaky social basis. That is guesswork, but documented guesswork.

Sometimes he seems to be over-controlled and only recently has he conquered a somewhat mannered habit of raising his right eyebrow while listening. This trick is thought by his handful of intimates to have been simply a product of nervousness, but its effect was superciliousness.

Extreme good looks are not necessarily a psychological asset. Not for a man. And any public reference to his facial appearance cracks his aplomb. It’s practically the only thing that does.

For a brief while during the war, for example, Taylor, a Naval flying instructor with lieutenant’s stripes, was stationed in Washington. And having led a pretty cloistered existence, he dropped in on one or two nightclubs with some friends. At one of these, a girl came over to his table, did a long, languishing take, and said with next to unbelievable gaucherie: “Gee, you’re the most handsome man in the world!” Taylor—quite literally—paled, got up from a half-finished dinner, and left the premises. He had been thrown the unanswerable observation and behaved accordingly. Yet, it is not likely another star would have been so completely unhinged—even one with less metallic poise.

Maturity has taken him out of the over-handsome class that once marked him—unfairly, by the way—as pretty. There is nothing un-masculine about his features; they are startlingly regular, that’s all. And even this doesn’t go for his nose. It is, without a mustache to underscore it, a trifle hawkish. And Taylor doesn’t wear the mustache “unless I’m using it”—i.e., unless it is necessary to a picture.

“Bob,” a friend has said, “could very well have an inferiority complex. He has it under check, naturally, but did you ever see a normal personality quite so contained as his? This guy never lets go. As a kid, he was pretty close to being a male beauty and this may have affected his relations with the other youngsters and set the framework for what he was going to be later. No one can say what he might have been if he hadn’t looked the way he does, but my guess is a solid Rotarian type who’d never get to Hollywood except for an American Legion convention. Or a cello player who liked to ride horseback or fly a rented plane weekends. He was pretty fair on the cello. But the face came along and crossed him up. Naturally, that’s pretty fair crossing. Big money, fame, the chance to live the way he wants to.”

Face or no face, Taylor has no vanity. Witness after witness has firmly deposed that so far as he is concerned, the mirror might as well not have been invented.

Probably the key to the Taylor character is his appreciation of independence. An inch has to be left here for guesswork, since Taylor is not given to self-analysis.

Independence is a better guess, anyhow, than “lonely” or “self-centered” or “solitary.” It implies a jealous regard for freedom of action. If this freedom were curtailed he would, in truth, become a morbidly unhappy man.

At the completion of Knights Of The Round Table, for instance, Taylor felt, as he usually does after any picture, an overwhelming urge to get out of town. He owns a Beechcraft—an eight-passenger plane that runs into a lot of money—but then, Taylor makes a lot of money.

So he and Ralph Couser, his long-time friend from Navy days and chief pilot for MGM, piled in and flew to Palm Beach. They had nothing special to do there but Taylor wanted to drop in on another friend to see if there was anything worth eating for dinner. There was. Later they flew back to New Orleans, one of Taylor’s war-time stations, and renewed a warming acquaintance with a restaurateur who interchanges normal false teeth with a set that are diamond encrusted. Still later they caught up with New York, where they dined one night with the entire chorus of the Copacabana nightclub line. It was reported in Hollywood that Taylor alone had taken the whole chorus out!

It was a junket at once aimless and genial, and Taylor happens to like that sort of dido. He flies to Illinois once in a while for no sounder reason than an evening of reminiscence with a Navy friend there; to South Dakota or Texas or northern California to hunt or fish; or to Alaska because he’d never been there.

Robert Taylor was born Spangler Arlington Brugh in Filley, Nebraska, a little more than forty years ago, the son of Ruth Adelia Stanhope and Dr. Spangler Andrew Brugh, the latter a sort of self-made physician. That is to say, the late Dr. Brugh, a grain dealer by vocation, adopted the study of medicine in middle life to try and find a cure for his ailing wife. His efforts paid off.

Eventually the family moved to Pomona, not far from Hollywood, and young Mr. Brugh did well in Pomona College’s senior class play, Journey’s End.

The rest of this is paralyzingly familiar. Talent scout. MGM contract. But-no parts. Discouragement. Encouragement—from L. B. Mayer. Small break. Big break—opposite Irene Dunne in Magnificent Obsession in 1936. Then the next eighteen years could not be called unalloyed clover, but they were pretty smooth going. There were no serious interruptions to Taylor’s screen career. The war arrested it but did not deflect its upward curve.

Taylor is in most respects an exemplary fellow. Punctual. Clean-cut. Doesn’t get loaded. Never, in lots of ways, left Nebraska.

The anecdotes that pursue him most often go like this one. He and Couser, his pilot friend, break down while en route by car to a fishing trip. Truck driver helps them out. Truck driver, who had at first regarded Taylor with truculent suspicion, warms to him over a few nips of Taylor-owned Scotch. Would have warmed to him anyway. “Tyler,” guy finally says, pronouncing it the way it’s spelled there, “you’re awright. First, I thought you were some so-and-so movie star.”

Then again, Taylor and Couser were flying once over some country that wouldn’t have been easy to sit down in, when the wings iced up and the propellers failed. They lost 10,000 feet before things got back to proper. Taylor, by solemn testimony of both, said nary a word during the whole excruciating experience. Stayed with the controls in taut-faced silence, just like in the movies.

“How could he talk?” Couser has said, in moving tribute. “He fainted!”

“That wasn’t it,” declares Taylor. “I was just scared speechless.”

The median fact is that Taylor is a competent, experienced pilot, and one who loves to fly. He’s a good shot, either hunt or skeet, a good man with a fishing rod and a better than good horseman. His tennis is inoffensive, his golf woeful and his knowledge of—and talent with—foods very commendable. He likes to eat simply and well—and he does like to eat.

“So,” said Taylor in summation, “we go back to the loneliness. If you want to regard it mathematically, it could be true. I have exactly two friends in Hollywood. Two. That may be counting it kind of close but it’s a good, round number. But if the way I live is loneliness, then it’s a different word from what the dictionary says it means. For me, it’s the happy way. And I still have a dollar that. says there are lots like me. And we mean it. We’re not taking a defensive attitude.”

And it was on approximately this note that the loneliest man in Hollywood went his lonely way, looking completely happy about it—happy as a clam or a guy who’d just knocked over a big lie about himself. And every bit as happy as bridegrooms are said to be.

THE END

—BY RICHARD MOORE

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE AUGUST 1954